I have been based in the Digital Imaging Unit, digitising the Roslin Glass Plate Slide Collection, since October last year as part of the ‘Science on a Plate’ project, funded by the Wellcome Trust’s Research Resources scheme. Recently, I became intrigued by the history of the glass plate slide itself so I decided to carry out a little research of my own.

Curious to discover where glass plate slides are positioned on the timeline of photography; what chemistry and techniques were involved in their making; and the role they played, I began with searching online and delving into some books on the history of photography.

The slides in the Roslin Collection date, loosely, between the late nineteenth century and the early twentieth century. This leads me to think that the majority of the slides are dry plate, gelatin-coated, slides as this was the most popular process used during that time period. Other processes, however, may have also crept in to the collection because different techniques and methods may have overlapped.

The slides are all positive, transparent images, with the nature of the images spanning; documentary photography, maps, statistics, instructions, illustrations, portraits, images taken from publications… the list goes on. Physically, the slides are all 3×3 inches in width and diameter, with a depth of roughly 3-6 millimetres. There are 3465 of them!

To give a little context, these slides might also be referred to as lantern slides. This is a term that relates to the fact that, early on, magic lanterns would be used to project similar looking slides. Magic Lantern (and Sciopticon) projectors had been used long before the invention of photography to project images painted on glass.

It was not until 1840 that the inventors of the daguerreotype began using magic lantern projectors in an attempt to project their photographic images for better viewing. The dull and foggy nature of the daguerreotype, however, did not lend itself well to the projection of light.

Next came the creation of the wet plate negative in 1851 by the Englishman, Frederick Scott Archer. This process involved coating glass plates with a collodian chemical and exposing light onto the glass while the chemical was still wet. This allowed for shorter exposure times when taking photographs. Previously, daguerreotypes (1839-1850’s) and calotypes (1841-1850’s) would require long exposures, often over one minute, forcing those being photographed to remain still in order to avoid blurring within the image. This is why daguerreotypes and calotypes often look posed and overly considered as compositions.

Accordingly, the colllodian wet plates gave a bit more flexibility when composing photographs. If, however, using the wet glass plate outwith the studio, photographers would have been required to carry processing chemicals and a portable darkroom as the wet plates would need developing immediately after exposure.

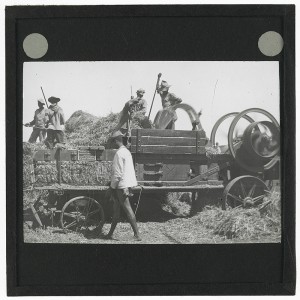

Photography remained a rather laborious procedure until the invention of the dry plate slide. In 1871, Richard Leach Maddox discovered that coating glass with silver bromide within a layer of gelatin would give more efficient photographic results; speedier and with a longer shelf life. The burden of hauling around chemicals and a darkroom was removed because the developing could be done at a later date by a specialist. In light of this photography became more accessible, opening up the practice to amateur photographers. Only the camera (camera models were becoming smaller and more portable over time) and the dry plates themselves were needed. Dry glass plates could be produced on mass, ready to use on the job. The act of taking a photograph therefore became less time-consuming, causing a change in the style of photographs being produced. This can be seen in the Roslin Glass Plate Slide Collection. On viewing many of the slides the camera seems to be there as a spectator, very much in the moment, giving the viewer a sense of what it mean to ‘be there’ – a relatively new phenomenon.

Roslin glass slide. A street hawker with his horse drawn cart standing next to a couple of children in Buenos Aires, Argentina in the late 19th or early 20th century.

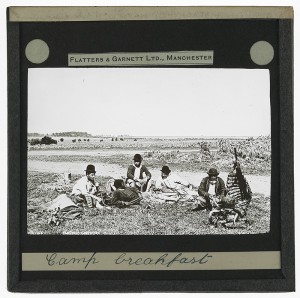

Roslin glass slide. A group of men eating breakfast in their camp on the plains in [Argentina or Uruguay] in the early 20th century.

Of all the various glass plate processes, the dry, gelatin-based plate had the longest run of success. It was not until the 1930’s when it was reduced to history with the introduction of nitrate film negatives and, namely the 35mm Kodachrome.

These slides were catalogued as part of the ‘Towards Dolly’ project and the Roslin Slide Collection can be viewed here.

Some useful reading:

Frizot, Michel, The New History of Photography (1994), Chapter 5

http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/collections/landscape/lanternhistory.html

http://archives.syr.edu/exhibits/glassplate_about.html

http://www.nfsa.gov.au/research/papers/2012/05/10/preserving-20th-century-glass-cinema-slides/

John

Project Photographer: Science on a Plate.

Fascinating blog post, John. Thank you!