Last Friday I delivered a talk on genetics in Edinburgh during the 1940s as part of the Scotland-wide Festival of Museums, for which Edinburgh University Library and Collections took the 1940s as its inspiration. This was of course a turbulent decade for the world in general, but not least for the science of genetics. In the four decades since the rediscovery of Mendel’s laws in 1900, scientists were gaining a greater understanding of the gene through the chromosome theory of inheritance and mutation studies, yet the discovery of the structure of DNA itself was yet to be discovered. The 1940s represented a crossroads for genetics, and Edinburgh was an important world player in its future.

Let us begin in the year 1939, when Edinburgh’s Institute of Animal Genetics hosted the prestigious 7th International Congress of Genetics. Originally scheduled for Moscow in 1937, the repressive Stalinist regime made this impossible. After some discussion, Edinburgh was chosen as the most appropriate location for the Congress, now rescheduled for the last week in August 1939. Over 40 Russian scientists were to give papers, alongside delegates from all over the world. However, it would not be plain sailing. Shortly before the Congress was due to begin, the director of the Institute Francis Crew received word that the Russians had been forbidden to attend, and the Congress programme had to frantically reshuffled. Things went from bad to worse once the Congress actually began, as war erupted across Europe and delegates from various countries began to return to their home countries while they could. Once the Congress was over, Crew, who was on the Territorial Reserve of officers, was mobilised, and posted to the command of the military hospital at Edinburgh Castle. He left the Institute in the hands of poultry geneticist Alan Greenwood.

During the lean five years which followed, the Institute did its bit for the war effort. The land adjoining the Institute building was used for allotments for growing animal feed and planting vegetables. All male staff joined the ARP or Home Guard as well as the Watch and Ward parties for the protection of University buildings, while the women were involved in First Aid work. The annual report for 1940-41 records that everyone was given ‘a daily dose of halibut liver oil to reduce the incidence of winter colds’! Genetics teaching and research continued as much as possible by a skeleton staff, including Charlotte Auerbach, who would make a major scientific discovery during this period.

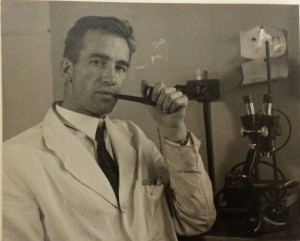

Charlotte (‘Lotte’ to her friends) Auerbach was from a scientific German Jewish family, and had sought refuge in Edinburgh after being dismissed from her teaching job in Berlin under Hitler’s anti-Semitic laws. Once established at Crew’s Institute, she had begun a developmental study of the legs of Drosophila, the fruit fly. But the arrival at the Institute of Hermann Joseph Muller in 1937 changed Auerbach’s career forever. Muller was the outstanding scientist of his generation: he had been part of Thomas Hunt Morgan’s famous ‘Fly Room’ at Columbia University in the 1910s, helping to formulate the groundbreaking chromosome theory; Muller’s later discovery that X-rays cause mutation, gained him the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. But he arrived in Edinburgh a broken man after undergoing political and racial persecution in America, Germany and the Soviet Union. Muller had a radical effect on the staff and students at the Institute, and he quickly interested Charlotte Auerbach in mutation studies.

In 1940, the year Muller returned to America, Auerbach and her colleague J.M. Robson were tasked with conducting research into mustard gas. They were not told the true nature of the work, which had been commissioned by the Chemical Defence Establishment of the War Office. Auerbach reported sustaining horrific injuries to her skin from working with the gas with inadequate apparatus, but it shortly became clear that the results were astonishing for the science of genetics. Mustard gas caused mutations in similar ways to X-rays. Although this important discovery had to be kept confidential until after the war, Auerbach would be awarded the prestigious Keith Prize from the Royal Society of Edinburgh for the work.

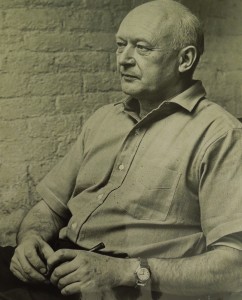

Once the war ended, it was assumed that Crew would return to the Institute and that research would continue much as before. However, Crew felt he had been left behind by recent advances in genetics, and decided to transfer to the Chair of Public Health and Social Medicine at the University. Around the same time, the government were looking to move scientific research into areas of agricultural interest, following the acute food shortage crisis of the war years. It was decided to establish a National Animal Breeding and Genetics Research Organisation (NABGRO, later ABRO), and Edinburgh’s strong track record in genetics, animal breeding research and veterinary medicine made it the obvious choice. Conrad Hal Waddington, a developmental biologist and embryologist, was appointed director of the new Genetics Section of NABGRO, which moved to occupy the more-or-less empty Institute building. Alan Greenwood moved to become director of the newly-formed Poultry Research Centre, next door to the Institute.

ABRO’s work was to be split between research into fundamental work on genetics and the applied science of animal breeding and livestock improvement. However, conflict soon arose between the experimental geneticists and the animal breeders, which was not helped by the rather bizarre initial arrangement of Waddington, his staff and their families living together under one roof, taking their meals communally and driving to work together every day. As might be imagined, there were some scandals and arguments, and eventually the arrangement disintegrated and administrative shifts took place to accommodate the rift.

Waddington set about recruiting as many promising research workers as he could, including some of his old army contacts from his days in Operational Research and Coastal Command. One scientist who joined the Institute at this time, Toby Carter, had been in the RAF at the time of the fall of Singapore, and had commanded the only boat to escape towards Java. A diploma course in genetics was established, and laboratory space increased apace. By 1951, Waddington’s staff numbered 90 and the Institute grew to become the largest genetics department in the UK and one of the largest in the world.

By the time the 1950s arrived, molecular biology was on the horizon, paving the way towards advances in genomics and biotechnology which we see today. Edinburgh has consistently remained at the forefront of these advances, but it is interesting to reflect that early organisations such as the Institute of Animal Genetics and ABRO paved the way, and that the 1940s was a hugely important decade for this evolution.

Clare Button

Project Archivist