Many of the scientists who feature in our collections were extremely well-travelled, and their archives abound with information about the conferences, congresses and conventions which they attended all over the world. However, it’s not often that we come across a real-life adventure story which very nearly didn’t have a happy ending…

Many of the scientists who feature in our collections were extremely well-travelled, and their archives abound with information about the conferences, congresses and conventions which they attended all over the world. However, it’s not often that we come across a real-life adventure story which very nearly didn’t have a happy ending…

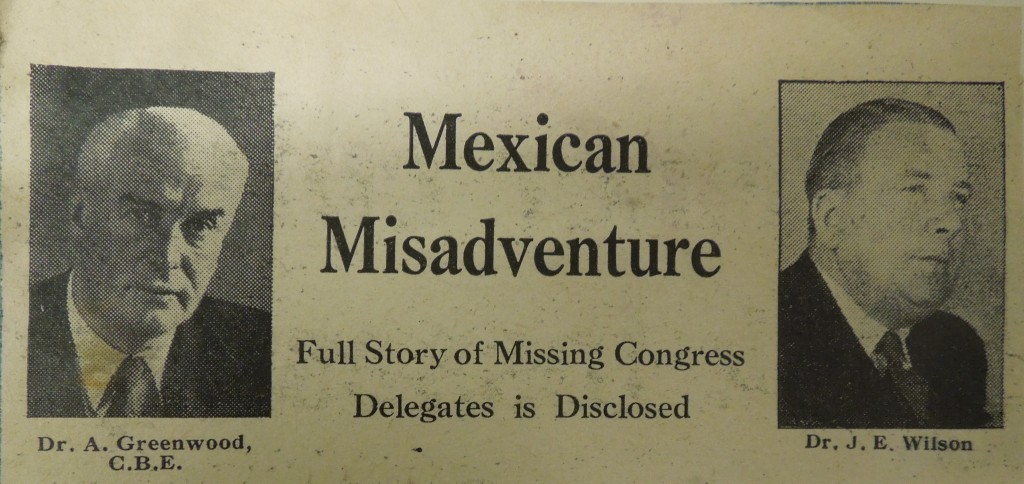

Among the papers of Alan Greenwood (director of the Poultry Research Centre in Edinburgh from 1947 until 1962) there is a press cutting from the Poultry World & Poultry magazine, dated 13 November 1958 under the headline ‘Mexican Misadventure: Full Story of Missing Congress Delegates is Disclosed’. The article goes on to tell the harrowing experience of Alan Greenwood and his colleague, veterinary surgeon James Ebeneezer Wilson, whilst journeying to a congress on poultry in Mexico City. Writing a personal account, Greenwood paints a vivid picture of the severe floods in Mexico which hit the country after a seven-year long period of drought. Arriving at El Paso ready to cross the Rio Grande to Juarez by train, all seemed to be going swimmingly: with the Chief Customs Official at the railway station providing them with free Mexican beer. The train departed at 10.30 on 18th September carrying 1,200 passengers, but got stranded at Jiminez the next morning when the rains hit. The delay was supposed to be around 10 hours, but as Greenwood reports: ‘in reality we spent four nights and four days on that train under circumstances which were not in the least bit comfortable.’ This is an understatement: with no hot water or light, limited sanitation and an infestation of cockroaches, the enforced confinement on the train was hardly pleasant. An attempt to cross a bridge by foot was aborted when it was discovered that the bridge in question had been swept away in the floods, so the confinement continued with the food situation growing ‘desperate’. At last, Greenwood and his colleague were able to get seats on a two-coach train trying to get from Jiminez to Chihuahua, but the drama continued:

It was a nightmare journey in many ways with the raging river torrents covering the trestle bridges over which we crawled at the rate of about a yard per minute. It was raining heavily all the time, and electrical storms were continuous. At times the carriages were jumping up in the air and leaving the tracks.

Greenwood and Wilson finally arrived in Chihuahua at 1am four days after they had left El Paso. After some days of rest and recuperation, the pair began the return journey to Houston. They continued to travel throughout America before returning to Scotland, and the Greenwood archive contains a book of postcards which Greenwood collected from around Mexico and America on this trip.

We probably all have travel ‘horror stories’, but probably none quite so hair-raising as this!

According to Burt’s report in the Roslin Institute’s Annual Report 1994-1995, the next challenge that they faced was to ‘locate and identify the defective gene in this (talpid3) mutant’ and that ‘a “positional cloning” approach could be used in which the talpid genetic locus itself is cloned and genes within that DNA are tested.’

According to Burt’s report in the Roslin Institute’s Annual Report 1994-1995, the next challenge that they faced was to ‘locate and identify the defective gene in this (talpid3) mutant’ and that ‘a “positional cloning” approach could be used in which the talpid genetic locus itself is cloned and genes within that DNA are tested.’