Response by: Holly Graham

Contributor: Katie Laurenson

Fieldworker: Elizabeth Neilson

© Gaada

My chosen object is a short audio extract, an excerpt of a longer oral history interview with Shetlander, Katie Laurenson; held within the School of Scottish Studies online collection of archive audio. I came across it while delving through another gathering of materials that has become an archive collection in its own right, hosted online by Shetland-based art space Gaada. Over the past year or so, Gaada have been working closely with local activist group Up Helly Aa for Aa (UHA4A) to collect a range of matter that together tells a story of the island’s annual local fire festival and its historic exclusion of women.

This assemblage of scanned press-cuttings, screen-shots of Facebook posts, drawings, videos, photographs and more, exists as a Google drive of digitised ephemera, documentation and artworks built collaboratively with contributions from UHA4A members. I had been invited, alongside a small selection of other artists, to explore this collection and to develop some accompanying artwork in the form of a flag design, and pieces for a display unit – outdoor structures that could allow for socially distanced viewing in the context of Covid19. A selection of these artworks were later donated to Glasgow Women’s Library.

As I read and surveyed images, a picture of the festival and what it meant to local people built in my mind – firearms, tar barrels, guizing, Vikings, community. The earliest festivals were “a highly ritualised form of mis-rule governed by the people” according to writer Callum G. Brown (Up-Helly-Aa: Custom, Culture and Community in Shetland, 1998); a show of what Brydon Leslie calls “disruption, devilment, and above all, flame” (New Shetlander, 2011). Brian Smith debunks the authenticity of what he terms the ‘bogus name “Up Helly Aa”’ and the festival’s links to Viking history, saying its inventors – young working men in Lerwick – ‘had their tongues firmly in their cheeks’ (The Shetland Times, 1993). Recent article headlines from local papers jostle and joust: ‘Is Up-Helly-A’ brazenly sexist, or is ‘the way it’s always been’ still acceptable?’ asks Peter Johnson in a 2017 issue of The Shetland Times; there’s a ‘Burning desire for change’ says Zara Pennington for The Orkney News in 2018; ‘Leave it as it is’ reads the opener of a letter from Lerwick resident Jolene Tindall for The Shetland Times in a year later; ‘Up Helly Aa sexism under the spotlight’ reads a headline of a 2020 Sunday Times article written by Shetlander Sally Huband; ‘They call us backward’ claims a staunch member of the ‘remain the same’ camp in a short video feature by Huck Magazine posted on their site in the same year.

There was a lot to look through, and I spent a number hours-worth of screen-time squinting at and zooming in on minute columns of newspaper text, lined by pixelated image boarders. The link to Katie’s sound file on the School of Scottish Studies website stood out to me as one of the only items in the Google drive present existing in audio format. It was a welcome pause from the glowing screen and I closed my eyes while I listened. Katie’s lilting narrative told of roots of the festival, steeped in sun-worship rituals. She spoke of flaming tar barrels and the healing properties of tar. She told her own anecdotes of being chastised for wandering to a neighbour’s house via a forbidden route.

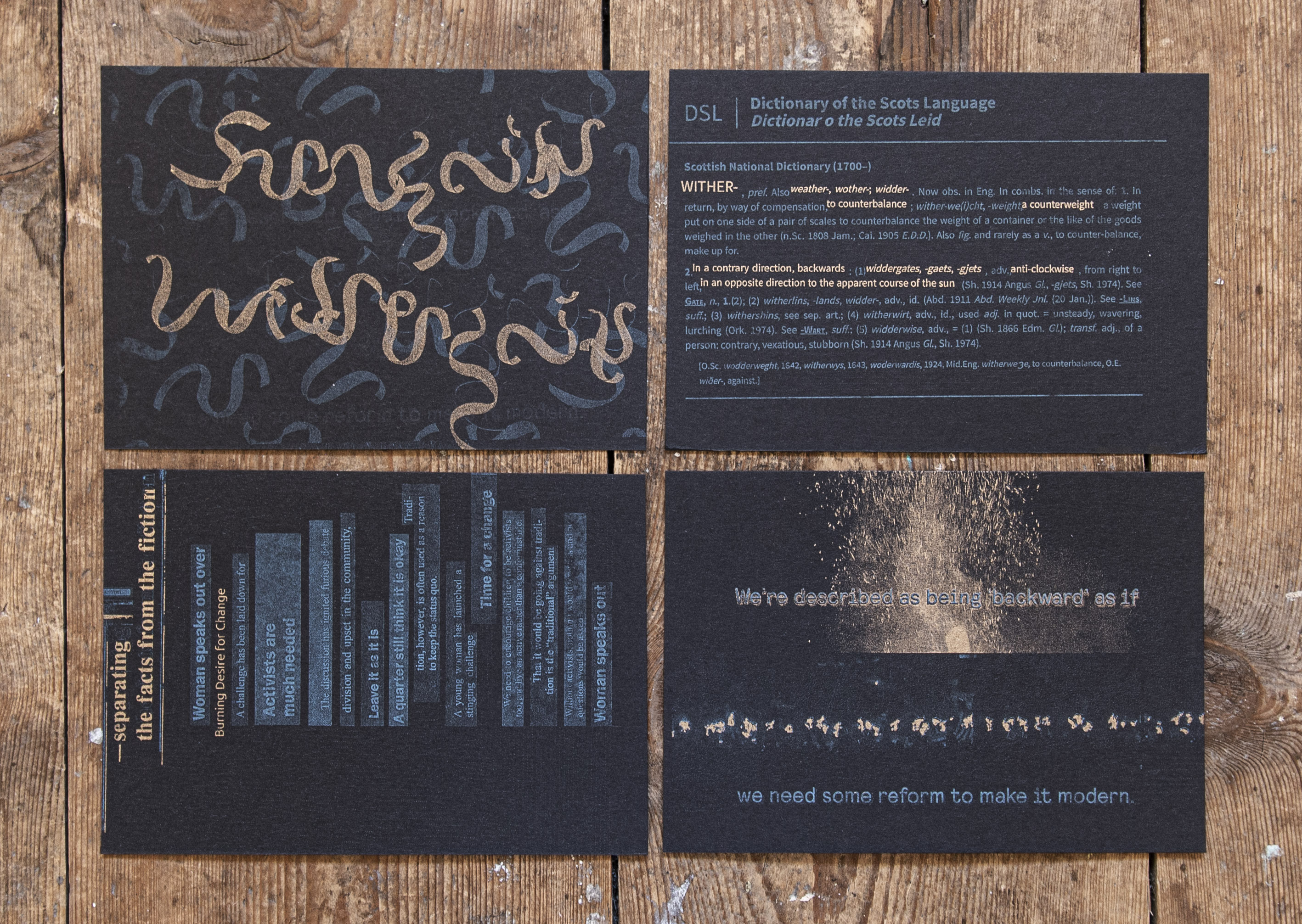

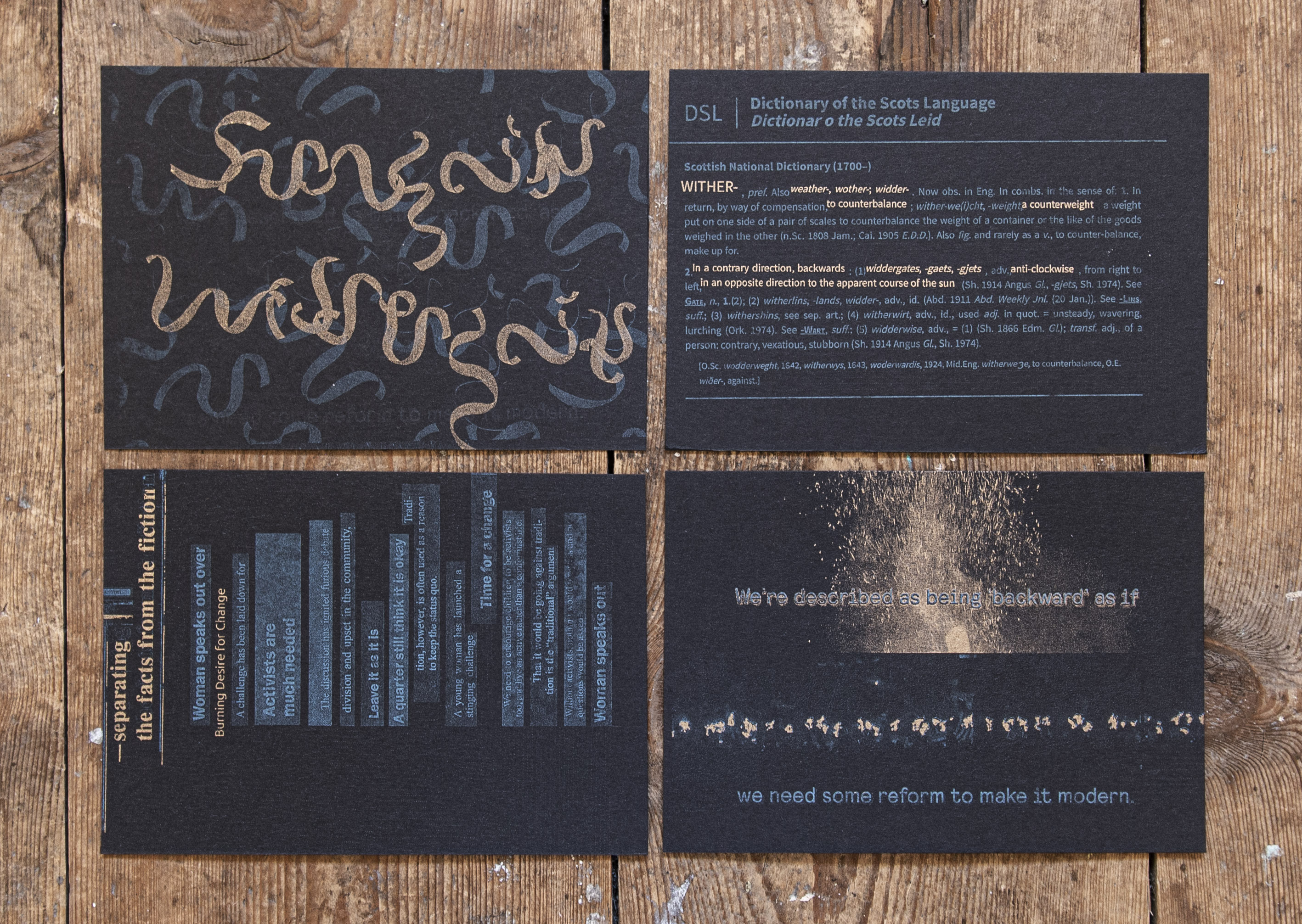

Postcards by Holly Graham

I often work with audio. I’m interested in story-telling and how individual voices present singular subject views, that listened to along-side others, can layer to build complex and nuanced narratives, versions of histories. I was intrigued by Katie’s recounting of her journey to the neighbour’s house and of how that mapped onto histories of the Up Helly Aa procession route, steeped in the superstitious belief that there was only one correct direction to move. Through Katie I learnt vocabulary that was new to me – ‘sungaits’, the way of the sun, also known as clockwise; and ‘widdergaits’, against the sun, or anticlockwise. She laughed at what ‘the old folks’ would say if they saw the present day Lerwick Up Helly Aa procession, weaving a figure of eight back and forth through the town centre. They’d think it was bad luck to travel in such a direction – they’d say ‘no winder you canna catch fish’. I liked this idea of tradition, superstition, direction, push-back and change.

From what I’d read in the Gaada and UHA4A collections of text, the main argument against women’s participation in the annual procession was one founded in tradition, in the notion that things had not changed before and should therefore not change now. But in light of Katie’s memories of the festival this case falls short. Katie was speaking in 1961, and her voice reaches us intact 60 years later, to speak some home truths to ‘this modern Up Helly Aa that you see nowadays’. And while speaking to us from the 20th century, Katie was born in 1890, just 9 years the first organised torch-light procession took place in Lerwick. Viewed through the span of a life and a voice – human for scale – we see the festival past as not so old, not so distant and concrete, impervious to change. We make traditions collectively, collaboratively. They are often built around small truths that in turn expand foam-like to form myths, and we pack further myths in around them, insulatory protective wrapping to transport them. They morph and change with time. Why would we not desire our traditions to be flexible enough to accommodate us, and to suit us societally as we move and shift, rather than remaining rigid restraints that constrict our collective growth?

The work I made for the project pivoted around a verbatim poem I assembled from Katie’s words, channelling the push and pull, forward and backward notions held by the terms ‘sungaits’ and ‘widdergaits’. The flag featured a mass of spiralling ribbons, and the two words – one on either face – constructed from these ribbons and enmeshed within them. The display case held a collection of prints: a collage of newspaper headlines, a dictionary definition of ‘widder-’, screenshots of a subtitled documentary on the festival and it’s accompanying calls for change. I also worked with other fragments of archive from the Scottish School of Studies collection; field recordings of songs sung and music played in the processions, recorded by Peter R. Cooke in 1982 [SA1982.010.011].

I pieced together an audio piece or ballad of sorts, that combined Katie’s voice with those of contemporary UHA4A women – Debra Nicolson, Joyce Davies, Lindsey Manson, and Frances Taylor – who echoed her words to form a chorus. The audio cycles, returning to familiar melodies played in reverse, words layered and repeated, the narrative is slippery. Together, tongues in cheeks, Katie and the UHA4A women chant: ‘No winder you canna catch fish!’

Holly’s flag flying at Gaada, in Bridge-End, Burra Isle.

________With thanks to Amy Gear and Daniel Clark at Gaada; Caroline Gausden at Glasgow Women’s Library; Louise Scollay at The School of Scottish Studies Archives and Library; Debra Nicolson, Joyce Davies, Lindsey Manson, and Frances Taylor of Up Helly Aa for Aa; Katie Laurenson and her family, and Peter R. Cooke.

______________

Thanks to Holly and Gaada for use of their images.

You can visit Holly’s website here: https://www.hollygraham.co.uk/

You can find out more about the project on Gaada’s website: https://www.gaada.org/weemins-wark

Up Helly Aa for Aa campaign: https://www.facebook.com/S4UHAE/about/

Glasgow Women’s Library: https://womenslibrary.org.uk/