It began as a simple cataloguing exercise. I noticed that a significant document in University of Edinburgh’s history had no representation in our online catalogue and set out to remedy this by creating a basic catalogue entry that could be elaborated on in due course. With a handy ‘caption card’ shelved alongside it, this was not a task that would take very long – or so I thought. I was soon in the midst of a famous murder!

The item in question was described, wrongly as it turned out, as the Clement Litill Charter. Litill, an Edinburgh merchant, had bequeathed a collection of 276 books to the ‘Town and Kirk of Edinburgh’ which effectively laid the foundation for Edinburgh University Library two years before the Charter which established the University itself and three years before the University opened its doors. It marks a foundational milestone in our history

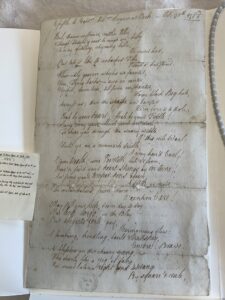

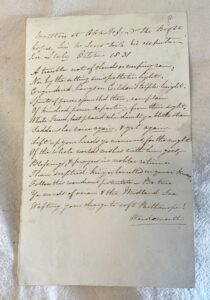

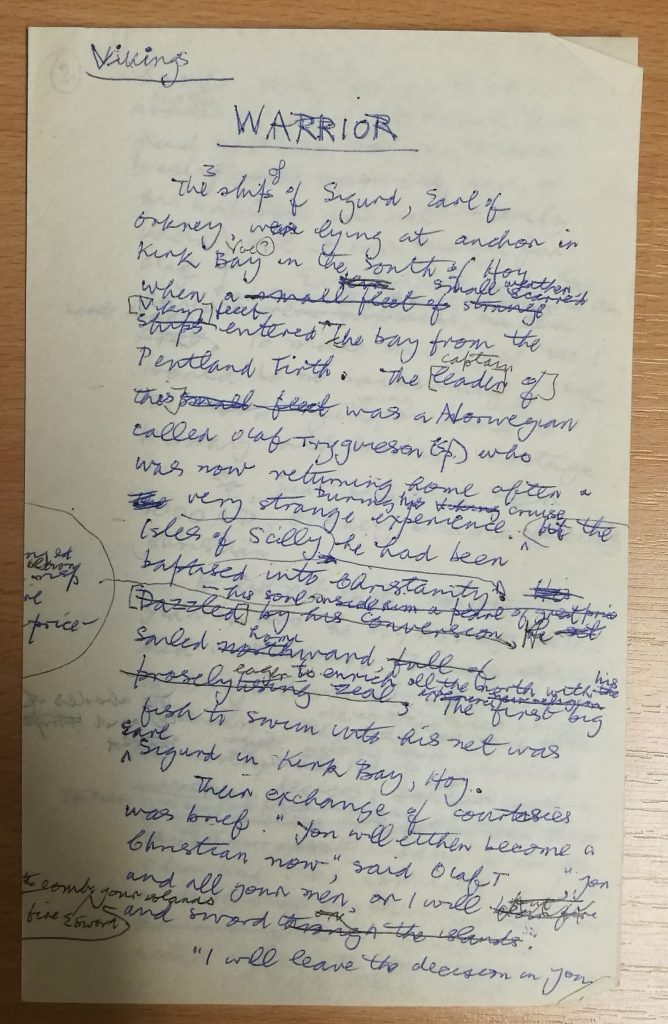

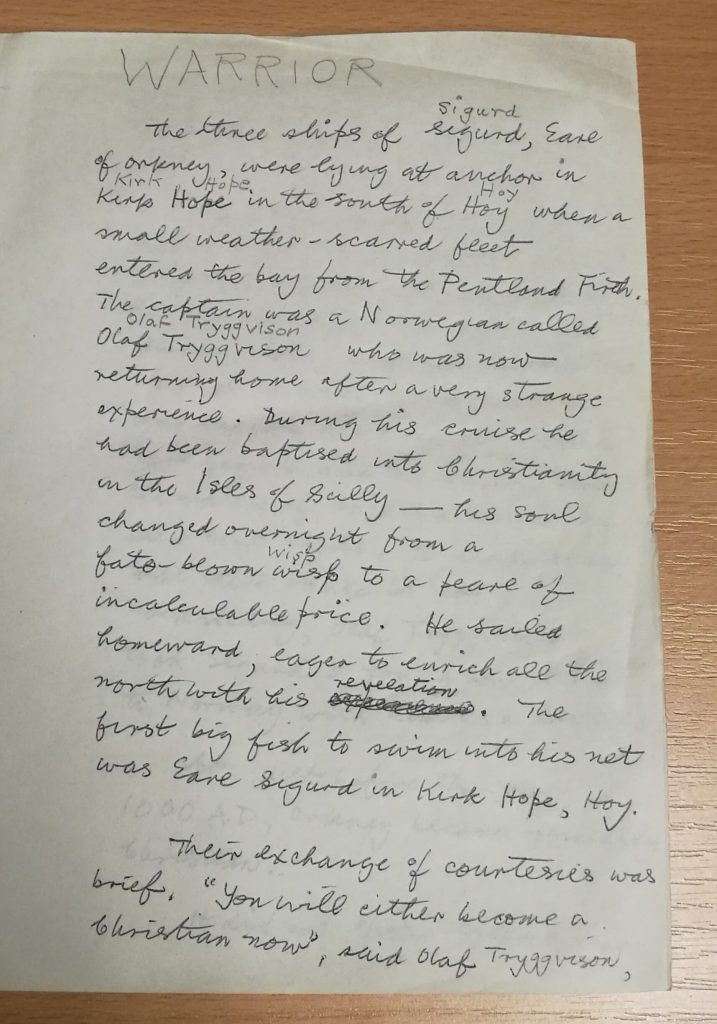

As it turned out, the document was not a charter. In fact there were three documents but with the third appearing to largely a wrapper for the other two. Of the other two, one was a document which was identified as having been drawn up by Alexander Guthrie, the Town Clerk, extracted from the Town Council minutes. As such, it was important to be as precise as possible about who Guthrie was.

Investigation of online sources, including a digitised copy of the Roll of Edinburgh Burgesses and Guild Bretheren, 1406-1700, identified three successive generations of Alexander Guthries who had served as Town Clerk. Which one was it?

Colleagues at Edinburgh City Archives were able to provide a list of Town Clerks and their appointment dates. In 1580, the second Alexander Guthrie took up office but it was unclear if he was in post by 14 October, when these documents were drawn up. At this point there was contradictory information as to who preceded him; the entry for the earlier Alexander Guthrie did not fully agree with the Edinburgh City Archives list. To try and better understand this discrepancy, I began to read the DNB article more fully and realised I was right in the middle of a key event in the history of the Scottish Reformation.

The article in question was written by Prof. Michael Lynch and identifies the eldest Alexander Guthrie as a ‘civic administrator and religious activist’, but that is only the start of the story. His wife, Janet Henderon or Henryson, “was one of the group of wives of influential burgesses with whom John Knox corresponded while in exile in Geneva. She was addressed as his ‘beloved sister’ in a letter of March 1558”. Guthrie himself worked closely with John Knox on consolidating the Reformation in Edinburgh. Unusually, he held both burgh and political office simultaneously. As Lynch notes,

His connections with Edinburgh’s legal establishment and with key protestant dissidents within the royal administration were demonstrated by the appearance in court as one of his sureties of Patrick Bellenden of Stenness, brother of the justice clerk John Bellenden of Auchnoull. In 1556 Guthrie had acted as godfather to one of the children of another influential legal family, the Bannatynes, which was in turn closely connected to the Bellendens.

Guthrie had suffered arrest for his activities during the Reformation crisis of 1559-60 but faced arrest again in 1566 when he was implicated in the murder of David Rizzio (or Riccio). He fled alongside fellow conspirators, was outlawed and lost his position as Town Clerk. This was a revelation. I had not come across Guthrie in any of the many lists of conspirators in academic and other accounts of this incident. Yet, as Lynch points out, “The fact that he was among the last of the Riccio conspirators to be granted a remission, in December 1566, when he was also restored to office, confirms his prominence in the affair.”

For those unfamiliar with the Rizzio murder, a quick summary. David Rizzio was secretary and possibly a lover of Mary Queen of Scots. On the evening of 9 March 1566, royal guards at the Palace of Holyroodhouse were overpowered by rebels who seized control of the palace. Rizzio was seized from the supper room, taken through adjacent rooms and stabbed 57 times. His body was then thrown down a staircase. (Read more on Wikipedia)

This is not the only high-profile murder of a royal figure in Edinburgh in this period, nor of one with a University connection. In February of the following year, Mary’s husband, Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley, who some thought was involved in Rizzio’s murder died as the result of an explosion in Kirk O’ Field House (roughly where our Old College quad is now situated) on. Suspicion fell on Mary and her future husband, the Earl of Bothwell. They were tried but acquitted. (Read more on Wikipedia)

But was Guthrie restored to office? This is where Lynch’s account and the Edinburgh City Archives list part company. His successor in 1566, David Chalmer(s), is recorded on the list with Chalmers then being succeeded by the second Alexander Guthrie in 1580. It may be the case that it was later determined that the elder Guthrie did not require to be reappointed to office – we can but speculate.

In terms of our archives, what is the significance of all of this? First, on the basis of current information, it is unclear which Alexander Guthrie drew up this document.

Second and more importantly, it helps situate the bequest of Littill’s books within the context of the time, this context being not just a backdrop but essential to understanding the significance of these events in the foundation of the University. Regardless of which Alexander Guthrie was involved, these were people working at the highest political levels within Edinburgh and Scotland. William Litill, who was responsible for honouring his brother Clement’s wishes, went on to become the city’s Lord Provost. The bequest was more than a beneficial transaction and those involved in seeing it fulfilled an executed were at the heart of the political turmoil of the period.

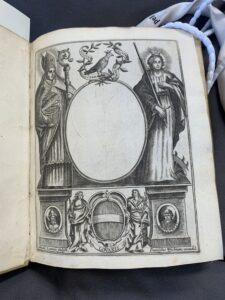

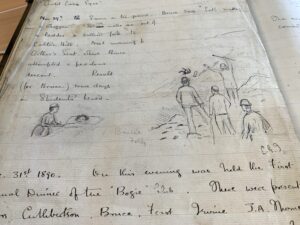

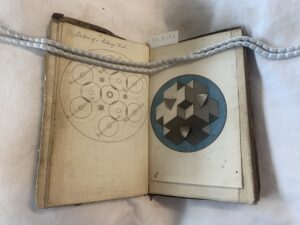

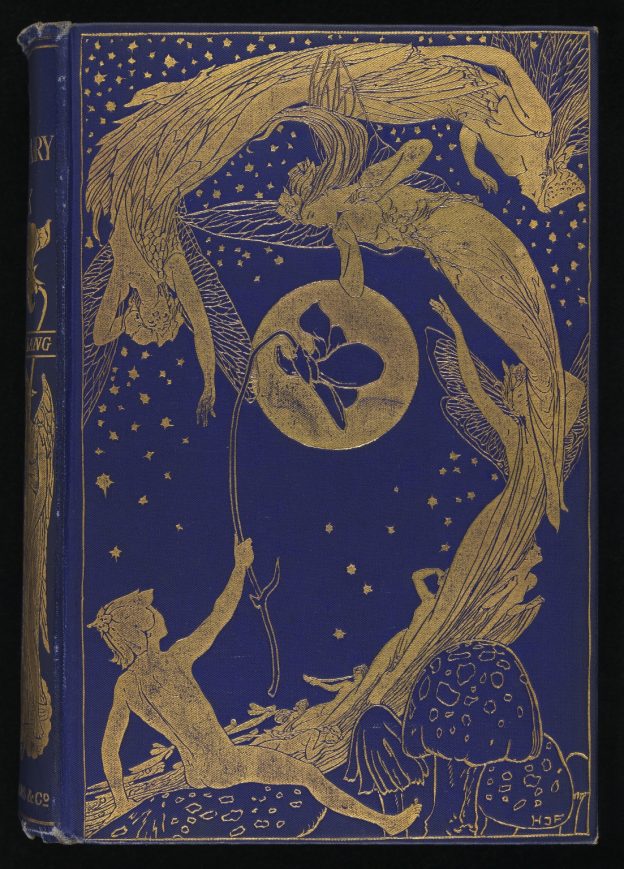

Book stamp, Litill bequest

Postscript

As an aside, the elder Guthrie features in elsewhere in our catalogue, in relation to two documents in the Laing collection.

Sources

- Watson, C.B.B., “Roll of Edinburgh Burgesses and Guild Brethern, 1406-1700” [https://www.tradeshouselibrary.org/uploads/4/7/7/2/47723681/roll_of_edinburgh_burgesses_1406_to_1700.pdf, last accessed 13 Septenmber 2024].

- Lynch, M., ‘Guthrie, Alexander (d. 1582), civic administrator and religious activist’ in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography [https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/69904, last accessed 12 September 2024].

- Town Clerks of Edinburgh 1363-1975, Edinburgh City Archives ECA16/1/23.