LAST LOSSES OF THE SECOND WORLD WAR, 1939-1945 – Christian Salvesen & Co.

22 March 2015 is the 70th anniversary of the sinking of the steam cargo vessel Empire Kingsley. Its sinking during the closing phase of the Second World War was the last maritime loss suffered by the general shipping and whaling firm Christian Salvesen & Co. of Leith during the War. Families couldn’t have known it at the time, but the ship’s destruction with the loss of 8 lives happened only 7-weeks before VE-Day (Victory in Europe).

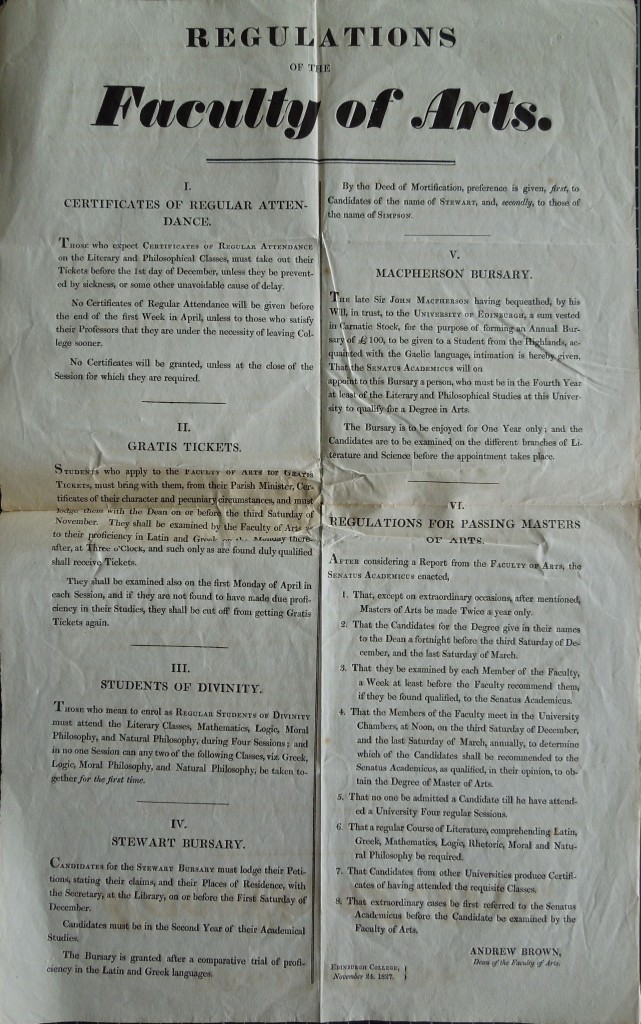

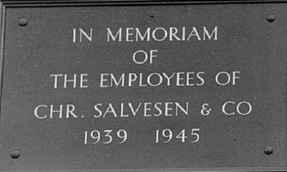

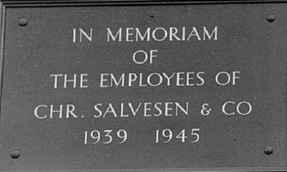

Memorial plate on homes built for the Scottish Veterans Association. Salvesen Archive. Coll-36 (2nd tranche. Photographs, ‘Garden cottages’, No.54)

The Empire Kingsley was one of a number of Empire vessels listed as Salvesen ships – other losses of these included the Empire Bruce, Empire Dunstan, and Empire Heritage (the latter being the firm’s greatest as far as lives were concerned with 60 crew dead) – and each was in fact owned by the Ministry of War Transport and managed on contract by Christian Salvesen & Co.

On Thursday 22 March 1945, on its way from Ghent to Manchester, the Empire Kingsley was sunk by a torpedo from the German submarine U-315 off Land’s End in Cornwall. U-315 surrendered at Trondheim in Norway a few weeks later in May 1945. It had hunted in several patrols since entering service with the German Kriegsmarine in July 1943, but had sunk only the Empire Kingsley and written off a Canadian frigate.

The British merchant marine suffered heavy losses during 1939-1945. Merchant ships and their crews suffered attack from submarines, surface raiders, mines and assault from the air. Christian Salvesen & Co. suffered no less than any other firm, indeed the whaling side of its business was all but suspended after the 1940-41 season. The firm’s transport ships and whale catchers were pressed into naval service under the control of the Ministry for War Transport, with its factory ships being used as tankers and heavy lift vessels.

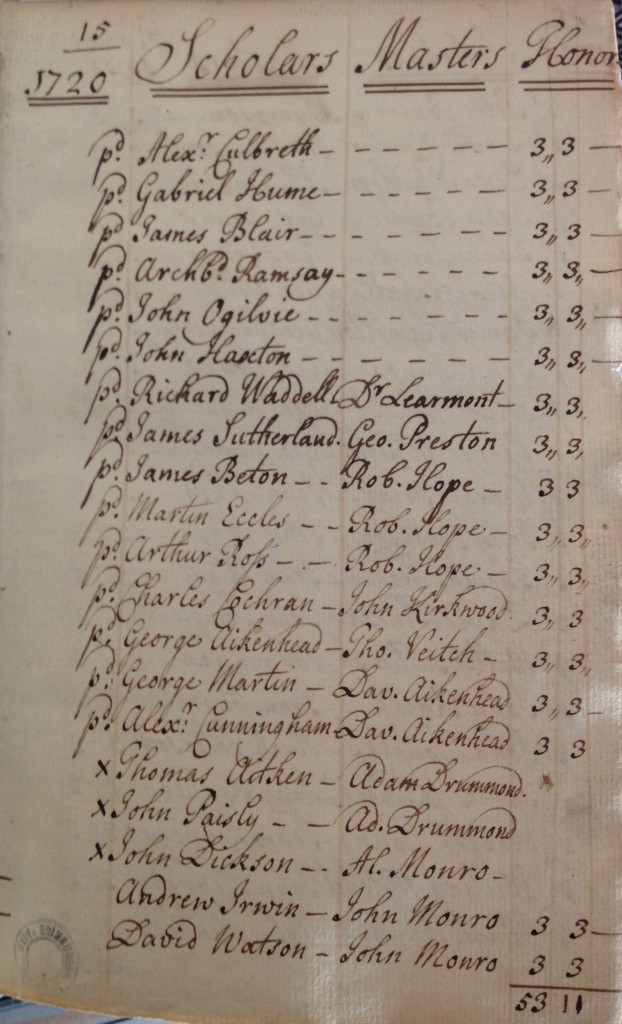

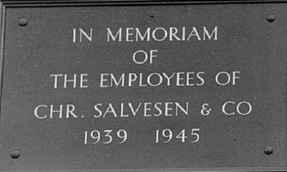

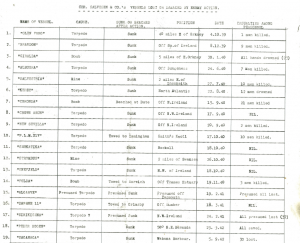

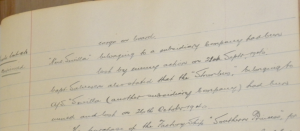

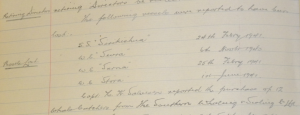

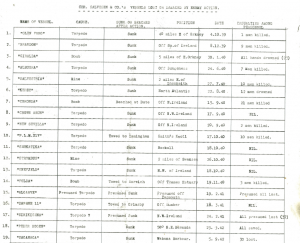

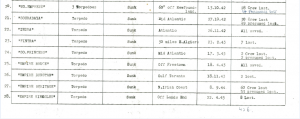

Contained within the Salvesen Archive (1st tranche. B2. Box 4.) is a copy of a list of Chr. Salvesen & Co.’s Vessels Lost or Damaged by Enemy Action… a list that records the deaths of over 400 seamen between October 1939 and April 1945, and the loss of Salvesen tonnage all over the world and around the home waters of the British Isles…:

The firm suffered its first wartime loss at sea with the sinking of the Glen Farg – a coaster – by the German submarine U-23 on 4 October 1939. The ship was on its way home from Norway to Methil and Grangemouth with a cargo of pulp, carbide and ferro chrome when it was captured and sunk off the north of Scotland, west of Orkney and Duncansby Head. One seaman was lost, but there were 16 survivors who were picked up by a Royal Navy destroyer based at Scapa Flow, Orkney.

The Salvesen vessel ‘Salvestria’ sunk by an exploding mine in the Firth of Forth, 27 July 1940. Salvesen Archive. Coll-36 (2nd tranche. C1. Photographs, No.1)

The loss of the whale factory ship Salvestria in July 1940 – on Edinburgh’s own doorstep – brought the deaths of 10 seamen. On 22 July 1940, two miles east of Inchkeith in the Firth of Forth, the ship was sunk by a magnetic mine while on its way to the naval installation at Rosyth with a cargo of fuel oil.

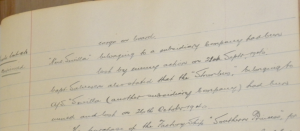

The loss of the vessels ‘Salvestria’, and ‘Shekatika’, and the attack on ‘Coronda’ reported in the Minutes of Meeting of Directors of The South Georgia Co. Ltd. […] 28 October 1940

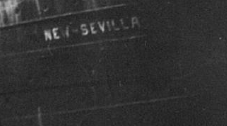

The same Minutes – 28 October 1940 – reported the loss of the ‘New Sevilla’

The same year, in September 1940, the whale factory ship New Sevilla was sunk off Northern Ireland – a bit out from Islay – on the way from Liverpool to Aruba and South Georgia.

‘New Sevilla’ sunk by a torpedo off Northern Ireland, 20 September 1940. Salvesen Archive. Coll-36 (2nd tranche. C1. Photographs, No.13 and 41)

The vessel was carrying a cargo of whaling stores when it was struck by a torpedo fired from the German submarine U-138. The attack could have had worse consequences as the human cost was 2 lives lost out of a total complement of 285.

The Salvesen vessel ‘New Sevilla’ sunk by a torpedo off Northern Ireland, 20 September 1940. Salvesen Archive. Coll-36 (2nd tranche. C1. Photographs, No.13 and 41)

Further west of Ireland, and south of Iceland, the Sirikishna was lost in February 1941. This steam cargo ship was on its way from Glasgow to Halifax, Nova Scotia, and had become separated from a convoy. It was attacked by the submarine U-96.

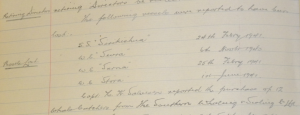

Pages from the Minutes of Meeting of Directors of The South Georgia Co. Ltd. […] 17 December 1941, reporting the loss of several vessels… ‘Sirikishna’, ‘Sevra’, ‘Sarna’, and ‘Stora’.

Not all attacks on Salvesen’s stock ended in a sinking. The vessels

Coronda,

P.L.M. XIV (a former French vessel taken as booty when France surrendered),

Folda, and

Daphne II were each either bombed or torpedoed but none of them were immediately lost. In September 1940, the steam-driven tanker and supply ship

Coronda (the second Salvesen vessel to bear that name… the namesake was the vessel that transported the first penguins to Edinburgh Zoo in 1913) was bombed in a German air attack off Northern Ireland on a journey from Iceland to Liverpool, carrying herring-oil.

‘Coronda’ , bombed but not sunk. Salvesen Archive. Coll-36 (2nd tranche. C1. Photographs, ‘Old Salvesen ships’, No.41)

Coronda suffered the loss of 21 seamen and suffered heavy fire-damage, and was beached on Kaimes Bay, Tighnabruaich, in the Kyles of Bute. P.L.M. XIV was torpedoed on Smith’s Knoll (part of the Haisborough Sands, off Norfolk) in October 1940 with the loss of 10 crew, and the vessel was towed to Immingham. In November 1940, Folda was bombed off the Thames estuary with the deaths of 3 seamen, and then the ship was towed to Harwich. Then, in March 1941, the vessel Daphne II was torpedoed off the Humber with no human loss, and towed to Grimsby.

The Salvesen vessel ‘Folda’ bombed in November 1940 and towed to Harwich. Salvesen Archive. Coll-36 (2nd tranche. C1. Photographs, Envelope ‘Norwegian lines and coasters’, No.45)

Not all the attacks on Salvesen’s ships ended in the deaths of crew. Between September and October 1940 the Crown Arun, Shekatika, Strombus and Snefjeld were each mined or torpedoed. The Crown Arun, known earlier as Hannah Böge, and taken into British service as war booty, then placed under Salvesen management by the Ministry of Shipping, sank off north west Ireland with a cargo of pit-props while in a convoy. Shekatika was sunk near Rockall en route to Hartlepool carrying steel and pit-props. Strombus broke up near Swansea after being attacked just as it was setting off for South Georgia, and Snefjeld sank north west of Ireland, also while in a convoy. None suffered human loss, and as has already been told Daphne II was attacked in 1941 with no losses either. Then, in March 1942, the tanker Peder Bogen was torpedoed, shelled and sunk south east of Bermuda by the Italian submarine Morosini, and again all crew were saved. The crews of the Indra lost in the Atlantic just above the equator in November 1942 and the Empire Bruce lost off the coast of Sierra Leone in April 1943 were also saved.

The Salvesen vessel ‘Peder Bogen’ torpedoed and sunk near Bermuda in March 1942, though all men saved. Salvesen Archive. Coll-36 (2nd tranche. C1. Photographs, No.18)

However, a few months after the loss of the Peder Bogen in March 1942 – and the saving of all the crew – the Saganaga was lost at anchor in Wabana Harbour, Newfoundland, in September 1942 with the loss of up to 30 lives. The steam cargo vessel loaded with iron-ore was sunk by a torpedo from the German submarine U-513.

The Salvesen vessel ‘Saganaga’ torpedoed and sunk in September 1942 with the loss of up to 30 lives. Salvesen Archive. Coll-36 (2nd tranche. C1. Photographs, No.47). Photograph by W. Ralston, Glasgow, and acknowledged by request

The Salvesen vessel Saganaga was reported in the Minutes of the Meeting of Directors of the Salvesen enterprise, The South Georgia Co. Ltd., on 30 December 1942, as having an insurance value of £155,000, which at today’s values would be circa £6.5-million. The Sourabaya which was lost earlier – in October 1942 – had an insurance value of £220,000, or £9.2-million today. Sourabaya was a whale factory ship and it was steaming in convoy from New York to Liverpool with a cargo of fuel oil, war stores and landing craft. It was torpedoed and sunk by the German submarine U-436 in the mid-Atlantic. 30 crew lost their lives.

![Notes on the 'Svana', 'Saganaga' and 'Sourabaya' in the Minutes of Meeting of Directors of The South Georgia Co. Ltd. [...] 30th December 1942. Salvesen Archive. Coll-36 (3rd tranche)](http://libraryblogs.is.ed.ac.uk/edinburghuniversityarchives/files/2015/03/Minutes_losses_30-12-42-300x277.png)

Notes on the ‘Svana’, ‘Saganaga’ and ‘Sourabaya’ in the Minutes of Meeting of Directors of The South Georgia Co. Ltd. […] 30th December 1942. Salvesen Archive. Coll-36 (3rd tranche. Minute Book)

Another whale factory ship was lost in October 1942 – the

Southern Empress. This ship was on its way to Glasgow, in convoy, and was also carrying a cargo of fuel oil and landing craft. In a position north west of St. John’s, Newfoundland, and south of Kap Farvel, Greenland, the Southern Empress was torpedoed and sunk by the German submarine

U-221.

The Salvesen vessel ‘Southern Empress’ sunk after an attack from 3 torpedoes fired by U-221off Newfoundland in October 1942. Salvesen Archive. Coll-36 (2nd tranche. C1. Photographs, No.41)

The greatest loss of life came in September 1944 when the tanker Empire Heritage, managed by Salvesen, was sunk by a torpedo north west of Malin Head, Ireland, on its way to Liverpool from New York. The vessel was carrying a cargo of fuel oil and a deck cargo including Sherman tanks when it was met by German submarine U-482. Over 100 lives were lost (of which 60 were crew). On 3 March 1945, the Salvesen vessel Southern Flower, formerly a whale catcher and which had been requisitioned for Admiralty service in anti-submarine duties, was torpedoed and sunk off the Icelandic coast by U-1022 patrolling between Bergen in Norway and southern Iceland. The Southern Flower had been owned by Salvesen since 1941 the year in which the firm acquired the Southern Whaling and Sealing Co. Ltd. from Unilever (Lever Bros.) along with its two whale factory-ships and fifteen whale-catchers.

![From the Minutes of Meeting of Directors of The South Georgia Co. Ltd. [...] 10th July 1945. Chaired by Capt. H. K. Salvesen. Salvesen Archive. Coll-36 (3rd tranche)](http://libraryblogs.is.ed.ac.uk/edinburghuniversityarchives/files/2015/03/Minutes_losses_10-July-1945-300x110.png)

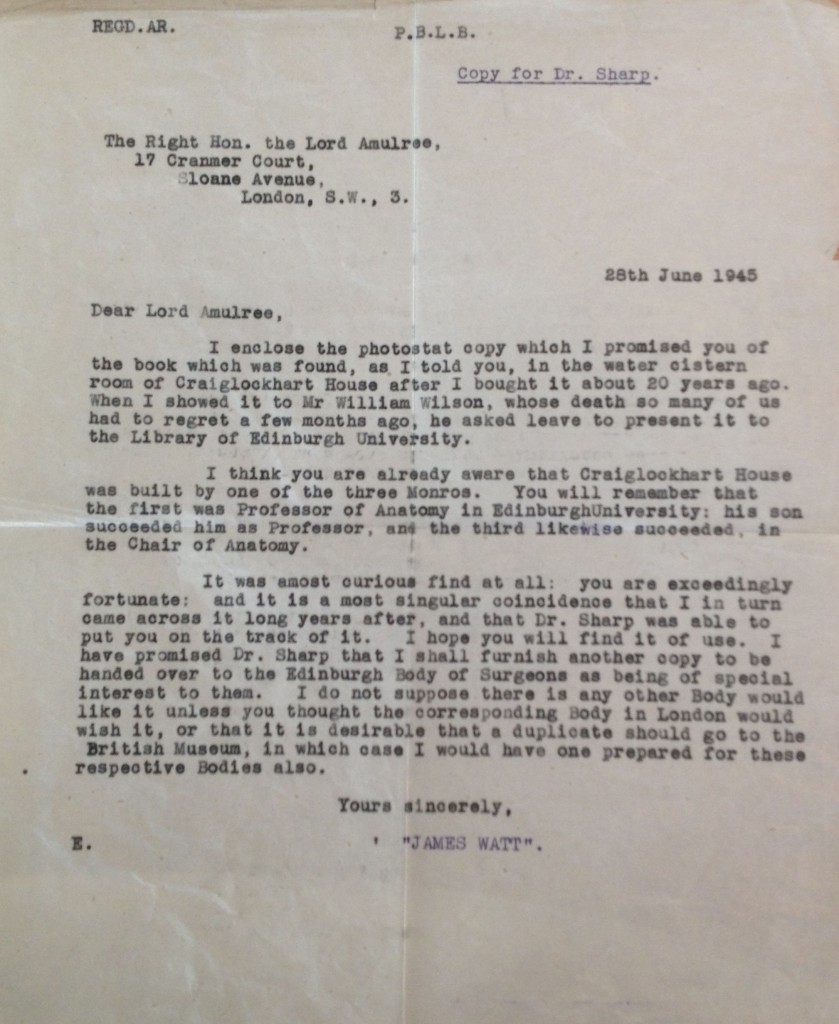

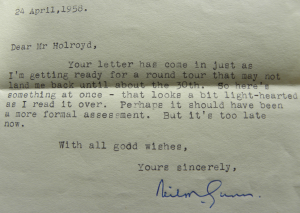

Notice of the vessels ‘Southern Flower’ and ‘Empire Kinglsey’ which had been lost to enemy action, from the Minutes of Meeting of Directors of The South Georgia Co. Ltd. […] 10th July 1945. Chaired by Capt. H. K. Salvesen. Salvesen Archive. Coll-36 (3rd tranche. Minute Book)

Then, later the same month the

Empire Kingsley was sunk off Land’s End with the loss of 8 lives from a crew of 57.

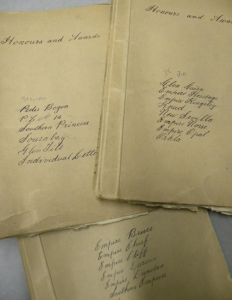

Correspondence files concerning honours and awards to officers and men serving on Salvesen vessels during the Second World War. Salvesen Archive. Coll-36 (2nd tranche. E2)

Many of Salvesen’s officers and men received awards for gallantry and for meritorious service at sea during the War, and others were commended.

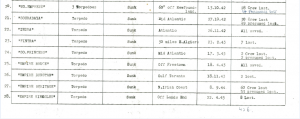

Pamphlet literature of the Scottish Veterans’ Garden City Association, 1940s. Salvesen Archive. Coll-36 (1st tranche. H14. File 1919-67)

Appreciation of the efforts and sacrifice of the seamen during the War years was met by Christian Salvesen & Co. through the establishment of a fund to assist the families of those whose lives were lost.

Memorial plate on homes built for the Scottish Veterans Association. Salvesen Archive. Coll-36 (2nd tranche. Photographs, ‘Garden cottages’, No.54)

Money was also made available from various members of the Salvesen family for the building of homes for veterans through the Scottish Veterans’ Garden City Association.

Homes built in Muirhouse, Edinburgh, were similar to those shown in the pamphlet literature of the Scottish Veterans’ Garden City Association, 1940s. Salvesen Archive. Coll-36 (1st tranche. H14 File 1919-67)

Construction of the houses designed in a ‘garden village’ style in Muirhouse, Edinburgh, was begun in 1946, and the houses were occupied by 1948. Streets were named Salvesen Crescent, Salvesen Gardens, Salvesen Grove, and Salvesen Terrace.

Dr. Graeme D. Eddie, Assistant Librarian – Archives & Manuscripts, Centre for Research Collections (Special Collections)

Sources used in this piece:

Salvesen of Leith. Wray Vamplew. Edinburgh: Scottish Academic Press, 1975; A whaling enterprise. Gerald Elliot; as well as internet wreck sites, and material contained in the Salvesen Archive

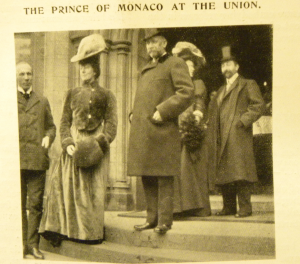

We recently acquired this photograph. It shows the committee which had responsibility for running the University Union, one comprised of both staff and students. We have researched each of the names and found out something further about most of them.

We recently acquired this photograph. It shows the committee which had responsibility for running the University Union, one comprised of both staff and students. We have researched each of the names and found out something further about most of them.

![Notes on the 'Svana', 'Saganaga' and 'Sourabaya' in the Minutes of Meeting of Directors of The South Georgia Co. Ltd. [...] 30th December 1942. Salvesen Archive. Coll-36 (3rd tranche)](http://libraryblogs.is.ed.ac.uk/edinburghuniversityarchives/files/2015/03/Minutes_losses_30-12-42-300x277.png)

![From the Minutes of Meeting of Directors of The South Georgia Co. Ltd. [...] 10th July 1945. Chaired by Capt. H. K. Salvesen. Salvesen Archive. Coll-36 (3rd tranche)](http://libraryblogs.is.ed.ac.uk/edinburghuniversityarchives/files/2015/03/Minutes_losses_10-July-1945-300x110.png)

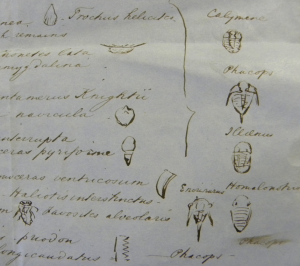

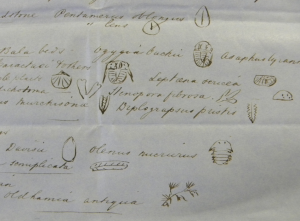

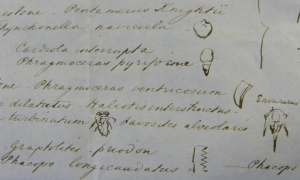

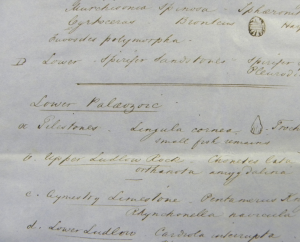

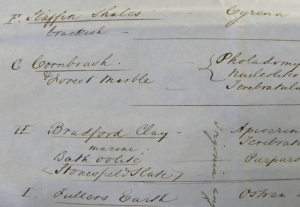

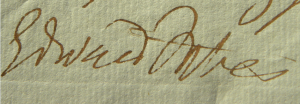

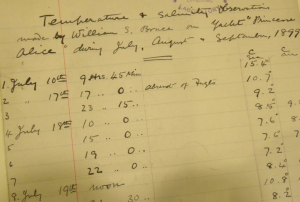

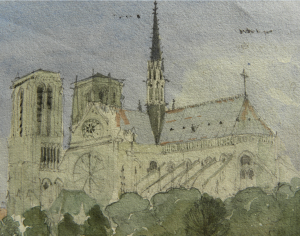

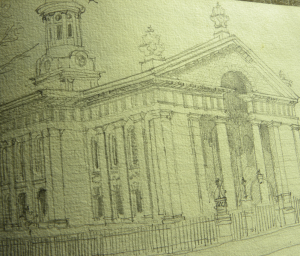

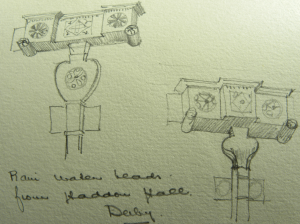

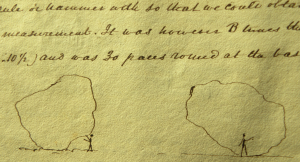

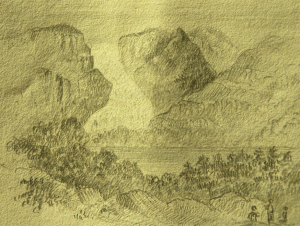

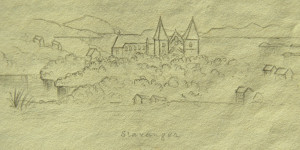

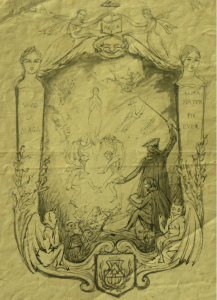

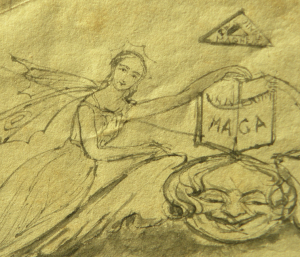

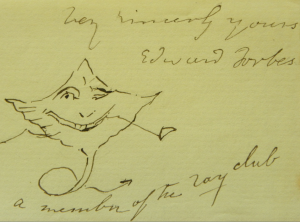

Throughout their work, ‘Memoir of Edward Forbes, F.R.S.’, Macmillan & Co., Cambridge and London, 1861, Archibald Geikie and George Wilson include vignettes and tail-pieces by Edward Forbes at chapter-ends… Probably not unlike these here. Gen.524.3.

Throughout their work, ‘Memoir of Edward Forbes, F.R.S.’, Macmillan & Co., Cambridge and London, 1861, Archibald Geikie and George Wilson include vignettes and tail-pieces by Edward Forbes at chapter-ends… Probably not unlike these here. Gen.524.3.