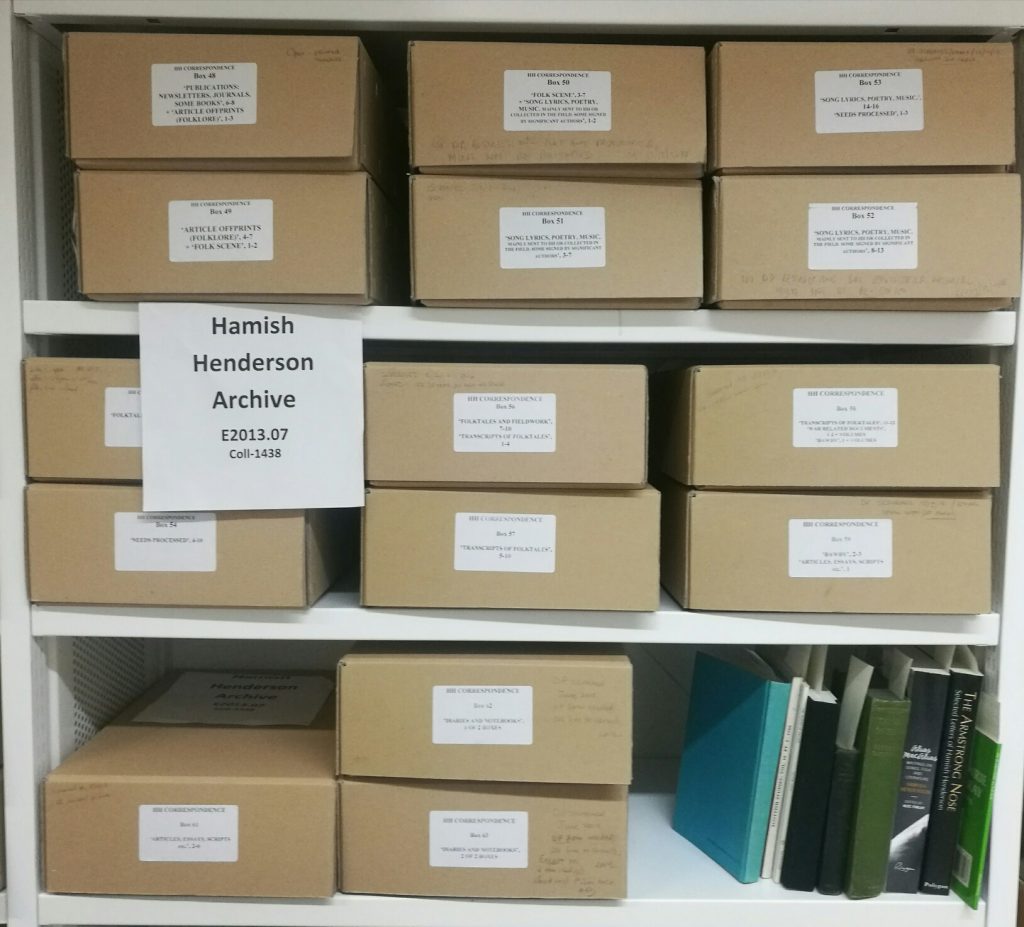

In popular culture, archives sometimes have a cryptic reputation: if some filmmakers were to be believed, in the middle of dust and darkness would rest ancient manuscripts and parchments containing secrets about the occult and the mystic, jealously kept by a lone archivist (or a librarian, since they often appear to be interchangeable)[1]. Even though archives do hold fascinating, touching, thought-provoking materials in a myriad of shapes and forms, any archivist would tell you that such a description is a bit more glamorous than the reality…or, is it? It turned out manuscripts can hold supernatural secrets, as I discovered in a mysterious (and bibliographic) quest started on a rainy autumnal Saturday…

Two years ago, while looking for something to do to entertain my French guests, I had found a web page describing an abandoned castle in the woods near Gifford, a small village 40-minute away from Edinburgh. It seemed like a lovely walk – and even better, a part of the castle was said to have been built in the 13th century by demoniac goblins summoned by a necromancer! Talk about intriguing. The three of us set off. The starting point of our walk was a little path heading into the woods in the middle of the countryside, near a lonely, faded Victorian house. This was a particularly rainy and quiet day; and our directions were not very clear – soon, we were lost. We knew the castle was there somewhere, ancient and hidden, but our position at the bottom of a small valley prevented us from seeing anything other than trees and colourful foliage. Eventually, we met three other walkers who sent us in the right direction. They smiled knowingly when we told them we were looking for Yester Castle, and told us they had left candles inside the vault, “for the atmosphere”… Even more intrigued, we continued our quest, passing a number of old stone bridges hidden by the autumn leaves: perhaps this trail used to be followed by the castle’s inhabitants and visitors?

One of the bridges on the way to Yester Castle.

Finally, after an ultimate bridge curved over the river running at the bottom of the glen, we caught sight of a stone wall at the top of a hill. There it was! We had found our castle! And thanks to the rain, we had it for ourselves. The first edifices we encountered were an impressive tall wall, and the ruins of the stone keep. The castle had been built in the middle of the 13th century by the Laird of Yester Hugo de Giffard (or Hugh Gifford), descendent of a Norman immigrant who had been given land in East Lothian during the reign of David I[2].

The tall wall leading to Yester Castle.

A remaining tower.

We soon spotted stairs descending into a cold, large, dark chamber. That must be it – the vault supposedly built by the same Hugo de Giffard, a man who left an ambiguous trace in historical records. Officially, we know he was one of the Guardians of the young Alexander III of Scotland; and one of the Regents of the Kingdom appointed by the Treaty of Roxburgh on 20th of September 1255[3]. However, he also had the reputation to be a warlock and a necromancer, and according to the legend he had summoned hobgoblins to build a subterranean vault under his castle, known as Bohall or Goblin Ha’, that he subsequently used for his demoniac activities.

The former entrance (?) of the vault.

The stairs leading down to the vault.

After wandering around the ruins for a while, we discovered a small entrance behind the castle, enabling us to enter the chamber by crouching through a narrow corridor in complete darkness. The size of the vault is still impressive today. The ceiling is high, and reminded me a stony, upside down rib cage. At one corner of the room there were stairs going down even more deeply into the ground. We were not disappointed.

Inside the Goblin Ha’.

Once back to the safety of our home, far from any threat of goblins or medieval wizard, we tried to learn more about this incredible place. Finding a trustworthy source for the occult legend surrounding Hugo de Giffard was not easy. The original citation on which a large part of Hugo’s dark reputation seems to have been built was quoted in his Wikipedia page as follows: “Fordun thus speaks of him in noting his death in 1267: “Hugo Gifford de Yester, moritur cujus castrum vel saltem caveam et dongionem arte demoniacula antiquae relationes fuerunt fabricatas,” (vol.ii, p. 105).” [4]. The quote can be translated as: “Hugo Gifford of Yester died. His castle, at least his cave and his dungeon, was said to have been formed by demoniac artifice”. The Wikipedia page for Yester Castle presented the same idea: “14th century chronicler John of Fordun mentions the large cavern in Yester Castle, thought locally to have been formed by magical artifice.”[5] This was very vague – there was no indication of the work where the quote had been found, and which edition… We decided to get to the bottom of things. After all, we thought, the ruins of a castle built by demoniac forces during the middle ages are only cool if it can be supported by genuine contemporary evidence, not some hearsay on Wikipedia!

The source was said to be Fordun – so we assumed at first that the quotation was from the Chronica Gentis Scotorum (“Chronicles of the Scottish people”) written by the Scottish chronicler John of Fordun in the 14th century[6]. This work was one of the first attempts to relate the history of the Scottish people, from its mythological origins to the death of David I in 1153. Which meant, of course, that it could not have mentioned Hugo de Giffard and his Goblin Ha’, built in the middle of the 13th century… We hit our first hurdle. To make matters more confusing, Sir Walter Scott himself mentions Hugo de Giffard and the infamous Goblin Hall in his book Marmion, published in 1808[7]. We wondered – was the quote just an imaginative addition from a 19th century author to give more credit to a local legend, inspired by Walter Scott’s novel? It seemed all the online mentions of this particular extract stemmed from the same inaccurate Wikipedia citation, copied and pasted in various websites. No recent scholarly publications available online seemed to examine the legend.

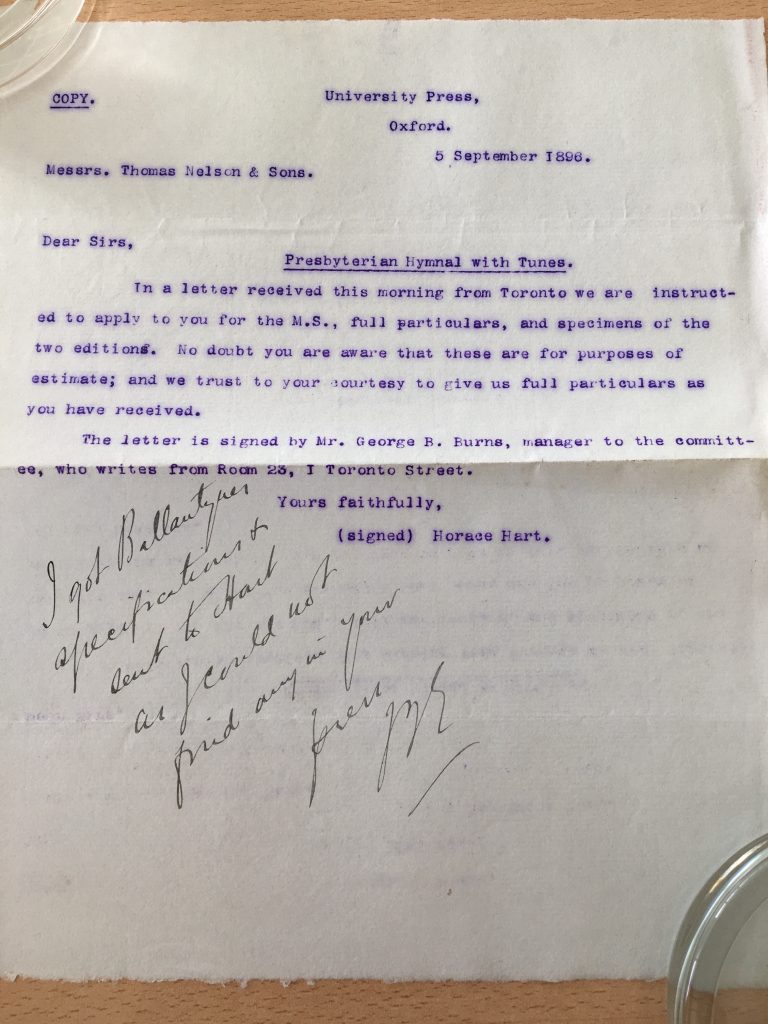

However, while reading more about Fordun and his chronicles, we did find a clue: in 1440 Fordun’s Chronica Gentis Scotorum was continued by a Scottish abbot named Walter Bower born around 1385 at Haddington in East Lothian, which is only a few miles away from our mysterious castle[8]. Ah! Could it be that the mention of the Goblin Ha’ was in Bower’s writings, rather than in Fordun’s chronicles? Bower, having grown up in the region, would have known about the local legend. The combined texts from Fordun and Bower are called the Scotichronicon, and are an invaluable source of Scottish history. Fordun was also commonly cited as the main author, especially in older sources, which would explain the mix up in the Wikipedia pages. The only edition available online was the Joannis de Fordun Scotichronicon: cum supplementis et continuatione Walteri Boweri, edited by Walter Goodall and published in 1759. Our Latin quote was in vol. 2, p. 105 – this seemed like the probable source of the Wikipedia entry, which mentioned a “vol. ii, p. 115”. Goodall’s work was for a long time the only complete edition of the Scotichronicon, and is based on Edinburgh University Library’s very own copy dating form 1510 (MS 186)[9]…

This is when I thought – why content yourself with a transcription when you can check the original source directly? I was at the time working with postgraduate students on a project to produce an online catalogue of our Western Medieval Manuscripts, so I took the opportunity to have a look at MS 186. I retrieved the medieval book, which is of an impressive size – it is one of the few manuscripts in our collection which still have its original binding, and I must say, it did look like my idea of an ancient esoteric grimoire full of dark secrets! I then located the capitulus X, liber 21 as instructed by the 1759 edition, and…. There it was! The very same sentence in Latin, about Hugo de Giffard and his vault built by Hobgoblins.

MS 186, with its original binding. The book measures 41 cm x 25 cm.

Original text in MS 186 – transcription in Latin – translation in English (from Scotichronicon, 8 volumes, ed. by D. E. R. Watt (Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press, 1987))

I later put our Wikipedia editing training to good use by fixing the entries and clarifying the source and the author of the quote. This marked a satisfying ending to our quest for truth – we could rest easy knowing that our mysterious castle was an authentic ghoulish lair, and that we had done our part in disseminating knowledge through accurate bibliographical sources – could any archivist ask for more?

Aline Brodin, cataloguing archivist at the Centre for Research Collections.

References:

[1] Oliver, A. Daniel, A., “The Identity Complex: the Portrayal of Archivists in Film.” in Archival Issues 37, no. 1 (2015): pp. 48-70.

[2] Ritchie, Robert L. G., The Normans in Scotland (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1954), p. 276.

[3] William Anderson, The Scottish Nation: Or The Surnames, Families, Literature, Honours, and Biographical History of the People of Scotland, vol. 2 (Edinburgh and London: A. Fullarton & co., 1862), p. 298.

[4] “Hugh de Giffard” (last edited in 2019), Wikipedia, Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hugh_de_Giffard (Accessed: October 2018).

[5] “Yester Castle” (last edited in 2020), Wikipedia, Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yester_Castle (Accessed: October 2018).

[6] “Fordun, John of”, in Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. 10, ed. By Hugh Chisholm, 11th edn. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1911). pp. 643-644.

[7] Scott, W., Marmion, 10th edn (Edinburgh: Archibald Contsable, 1821), p. 157.

[8] Watt, D. E. R., “A National Treasure? The Scotichronicon of Walter Bower”, in The Scottish Historical Review, Volume LXXVI, 1: No. 201 (April 1997), pp. 44-53.

[9] Scotichronicon, 8 volumes, ed. by D. E. R. Watt (Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press, 1987). See in particular, ‘Introduction’ to Volume 1 and Volume 8.