Another way we promote the project is by giving talks and last Wednesday we had the exciting opportunity to collaborate with both ASCUS: the Art and Science Collaborative and Dr. Mhairi Towler and Paul Harrison of Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art, Dundee. Our part of the talk was to introduce the collection to a wider audience and to show the wealth of material on offer to researchers; then, the artists, Dr. Mhairi Towler and Dr. Paul Harrison spoke about their current project sand how they used some of the material from the Conrad Hal Waddington Collection in their work.

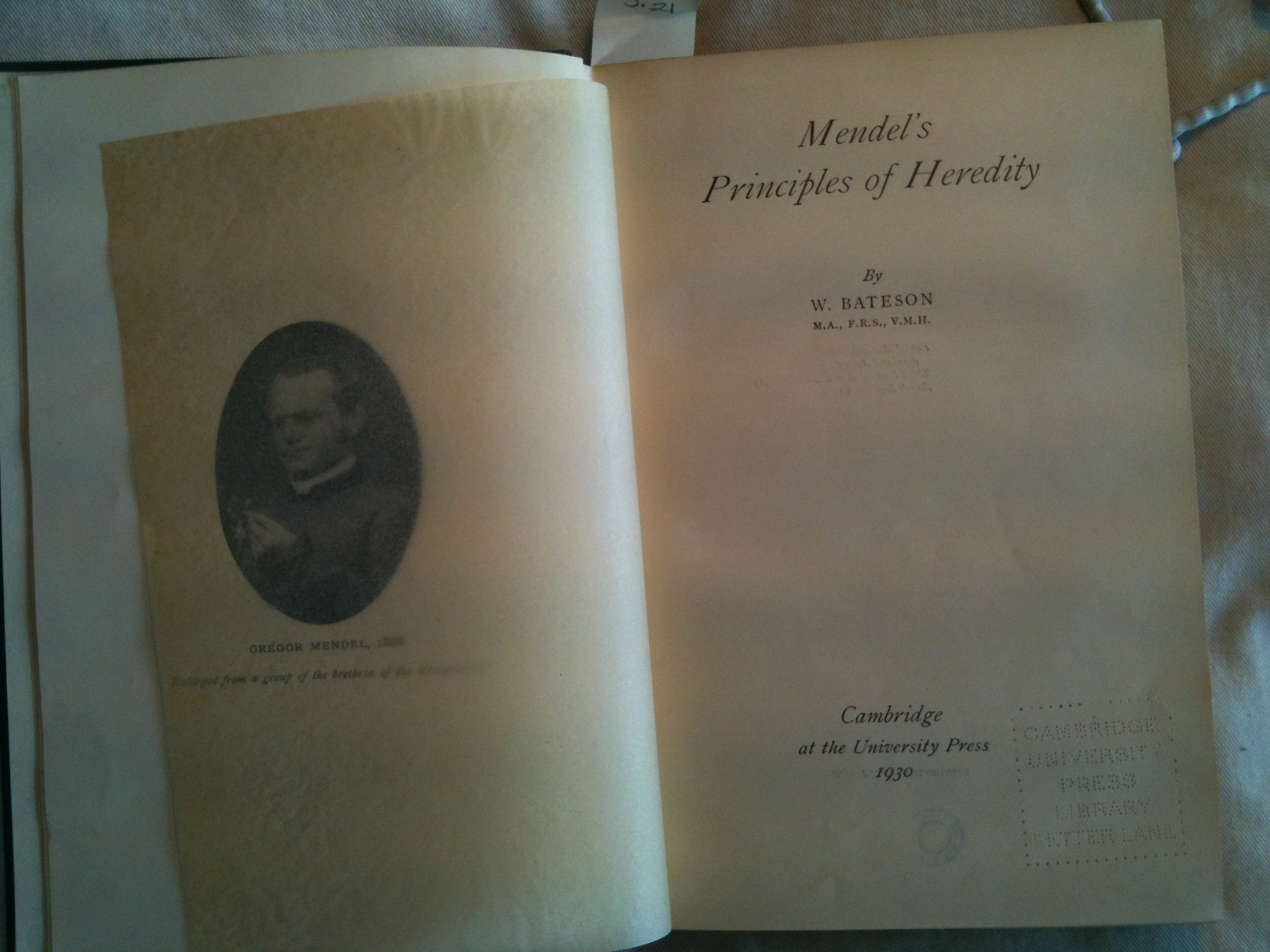

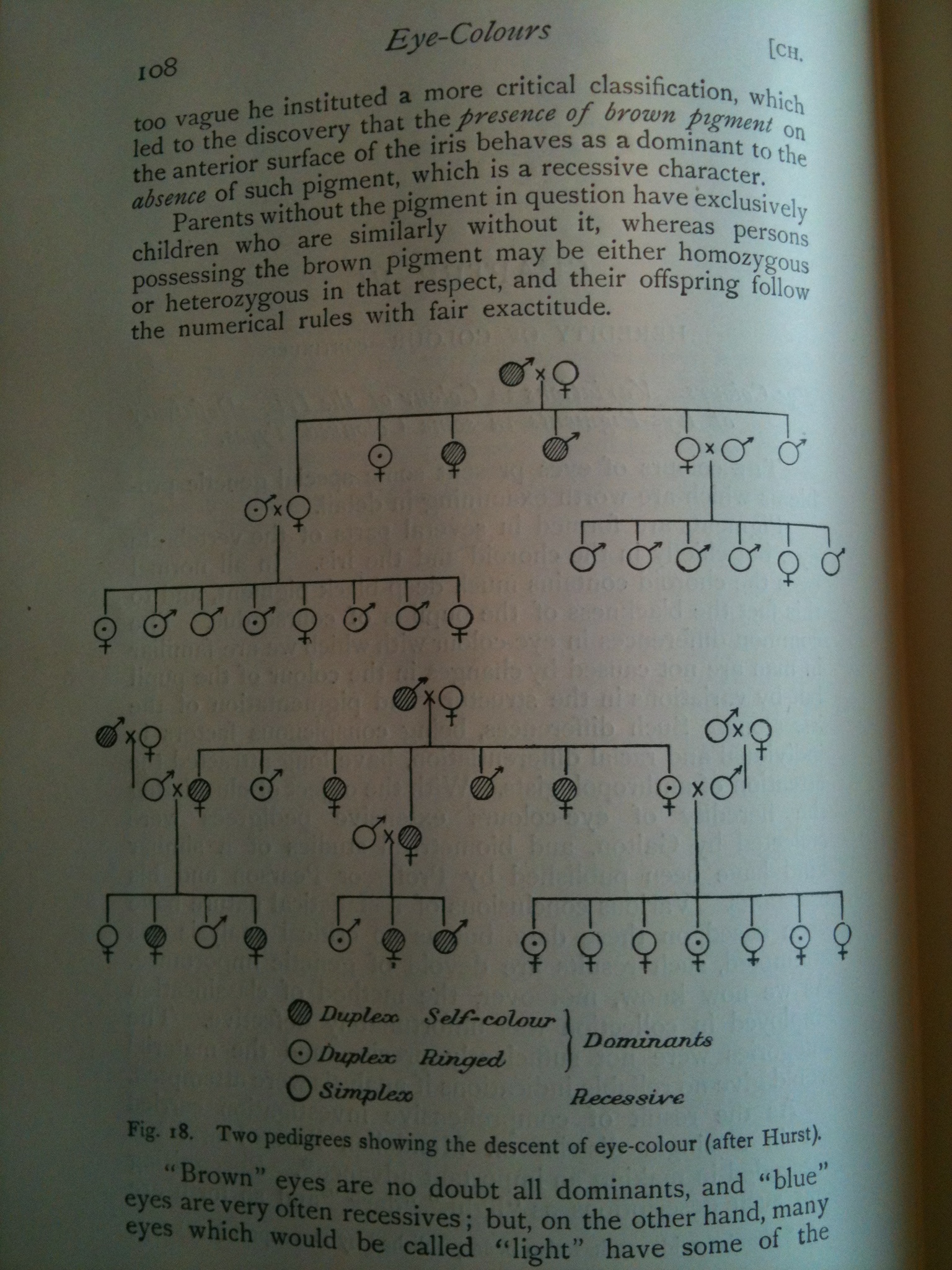

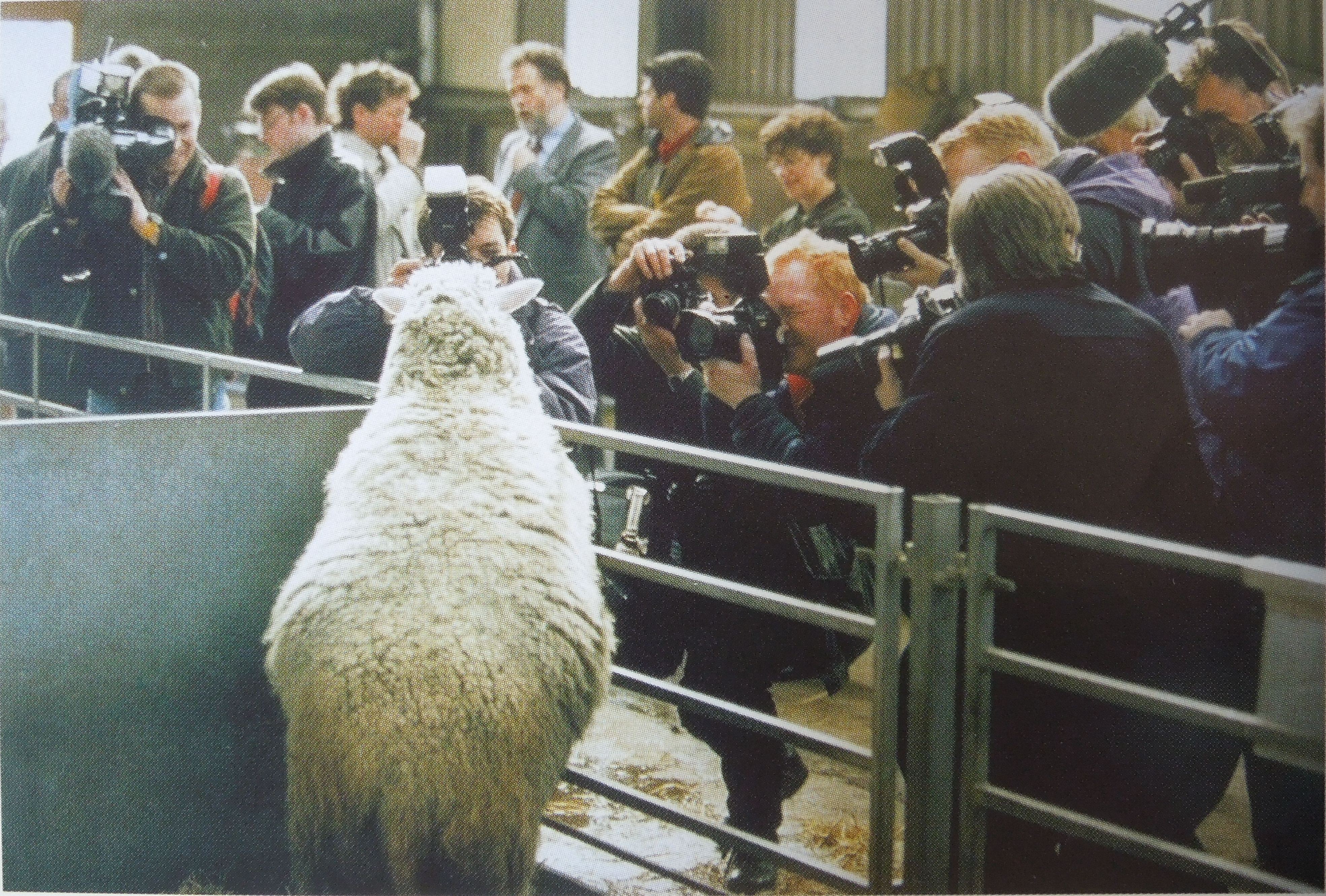

Our talk: ‘Towards Dolly: Edinburgh, Roslin and the Birth of Modern Genetics’ is based within Edinburgh University Library’s Centre for Research Collections and is generously funded by the Wellcome Trust’s Research Resources in Medical History grants scheme. The project archivist, Clare Button, and rare books cataloguer, Kristy Davis are cataloguing the archival records of the Roslin Institute, the Institute of Animal Genetics, the papers of James Cossar Ewart and Conrad Hal Waddington, glass plate slides, rare books and scientific offprints.

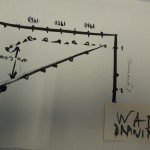

And Dr. Mhairi Towler and Dr. Paul Harrison of Duncan Jordanstone College of Art in Dundee spoke on their artwork based upon the C.H. Waddington collection who presented aspects of their work in progress: ‘Epigenetic Landscapes’. This research they said ‘explores and celebrates the ideas of developmental biologist, philosopher and visual thinker, C.H. Waddington.’ http://www.designsforlifeproject.co.uk/ Afterwards there was a brief question and answer session before people left or moved on to discuss it further.

We would like to thank Dr. Mhairi Towler and Dr. Paul Harrison for speaking; ASCUS for collaborating with us to make this event possible; the Art and Science Library at Summerhall for letting us use their space and all those who braved the weather and attended the event.