Cataloguing the correspondence of zoologist/animal breeder James Cossar Ewart (1851-1933), I have been intrigued by the various ‘life stories’ which emerge from the letters. Periodically I will be including some highlights in a series of posts entitled ‘letters in the limelight’ .

Cataloguing the correspondence of zoologist/animal breeder James Cossar Ewart (1851-1933), I have been intrigued by the various ‘life stories’ which emerge from the letters. Periodically I will be including some highlights in a series of posts entitled ‘letters in the limelight’ .

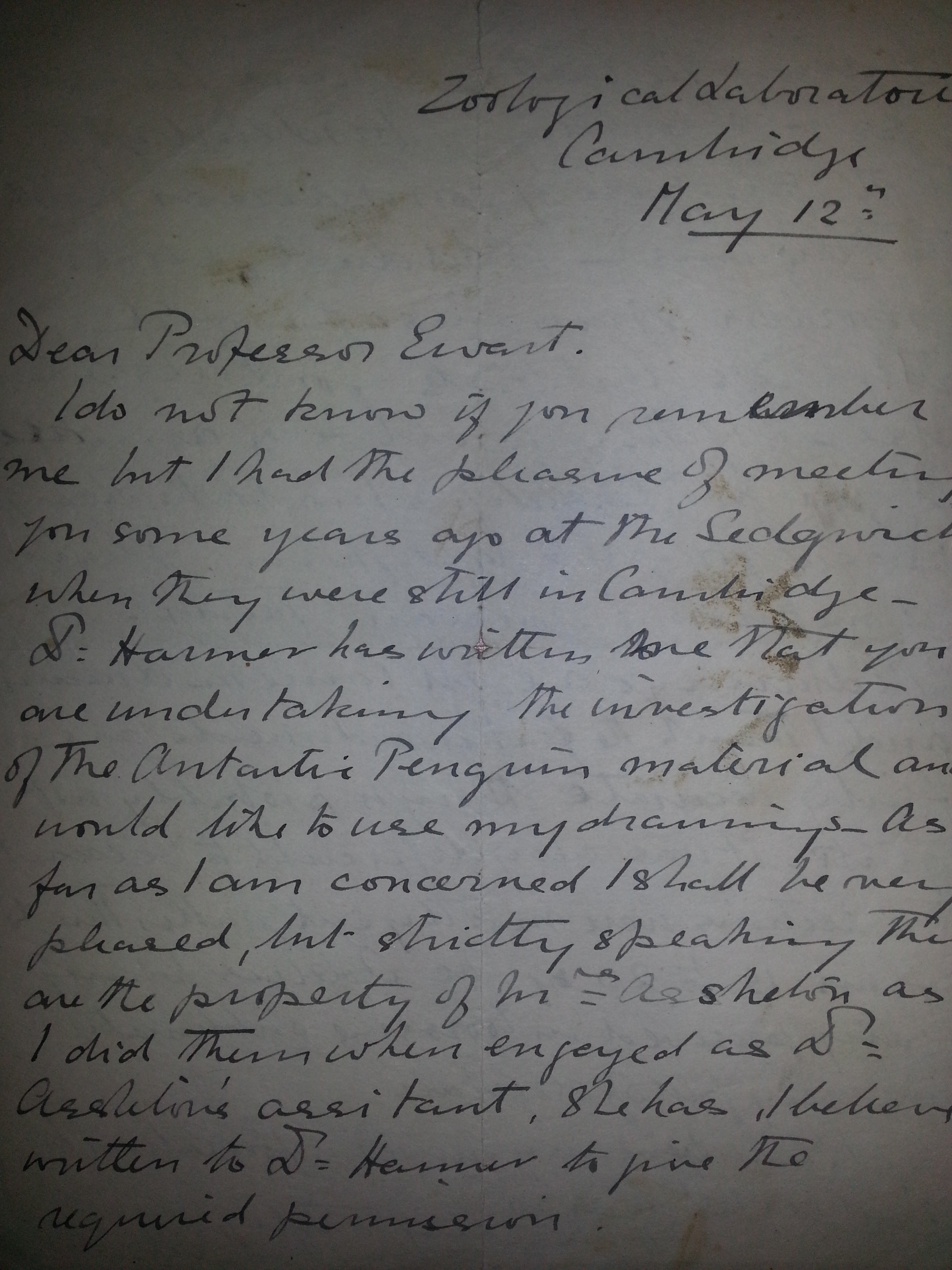

‘Dr Harmer has written me that you are undertaking the investigation of the Antarctic Penguin material’, writes Dorothy Thursby-Pelham to James Cossar Ewart, ‘and would like to use my drawings. As far as I am concerned I shall be very pleased, but strictly speaking they are the property of Mrs Assheton as I did them when engaged as Dr Assheton’s assistant. She has I believe written to Dr Harmer to give the required permission.’ The letter, dated 12 May, gives no reference to year, although it is likely to be from around 1922 when Ewart was conducting research on the Emperor Penguin. He had been interested for a number of years in exploring the origin and history of feathers in birds and their possible relation to scales on reptiles. Examining Thursby-Pelham’s drawings of embryonic penguins would have allowed Ewart to make a study of the process of early feather development.

Thursby-Pelham, a scientist at the Zoological Laboratory, Cambridge, has been called ‘England’s first female sea-going fisheries scientist’ and was an active member of the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea. However, as she mentions to Ewart, she had also worked as an assistant to Dr Richard Assheton (1863-1915), Lecturer in Animal Embryology at the University of Cambridge. The drawings to which Thursby-Pelham refers, and which Ewart evidently wished to use as part of his research, were the intricate and beautiful pencil drawings of the embryos of the Emperor Penguin eggs famously collected on Scott’s last expedition (1910-1913) to the Antarctic. This expedition, commemorated in Apsley Cherry-Garrard’s 1922 book The Worst Journey in the World (which contained Ewart’s report on the Emperor Penguin as an Appendix), aimed to be the first to reach the South Pole, collecting as much scientific data as possible along the way. In particular, it was hoped that evidence would be found about the embryos of Emperor Penguins (thought to be the most ‘primitive’ of the bird species) to support the theory that there was an evolutionary link between birds and reptiles. In 1911, Edward Wilson, the expedition’s chief scientist, and two colleagues embarked on a gruelling five week journey to the nearest penguin breeding colony, pulling heavy sledges in total darkness through temperatures of -40°C. They collected five fresh eggs, three of which survived the return journey. Back in Britain, the pickled embryos were sliced and mounted onto slides, with Richard Assheton being assigned the special task of analysing them. It was at this time that Dorothy Thursby-Pelham made her pencil drawings. Meanwhile, the bodies of Scott, Wilson and a third colleague, Henry Bowers, were discovered in 1913, having perished in the cold on the return journey from the South Pole (they were beaten to the spot by Roald Amunsden’s Norwegian expedition).

The outbreak of the First World War and Assheton’s death delayed the detailed study of the embryos until 1934 – the year after James Cossar Ewart’s death – when advances in science had discounted the theory of a link between between an embryological development and evolutionary history. However, the eggs, which can still be seen today in the Natural History Museum, remain as poignant reminders of the courageous and often deadly battle for scientific discovery.

You can see images of the eggs, as well as pictures from Scott’s expedition and one of Dorothy Thursby-Pelham’s drawings here:

http://www.nhm.ac.uk/mobiletreasures/specimens/penguin-egg/index.html