Now that spring has arrived and with National Hunt season ending and Flat Season beginning, I thought I’d show you some horse racing images we have in the Roslin glass plate slide collection.

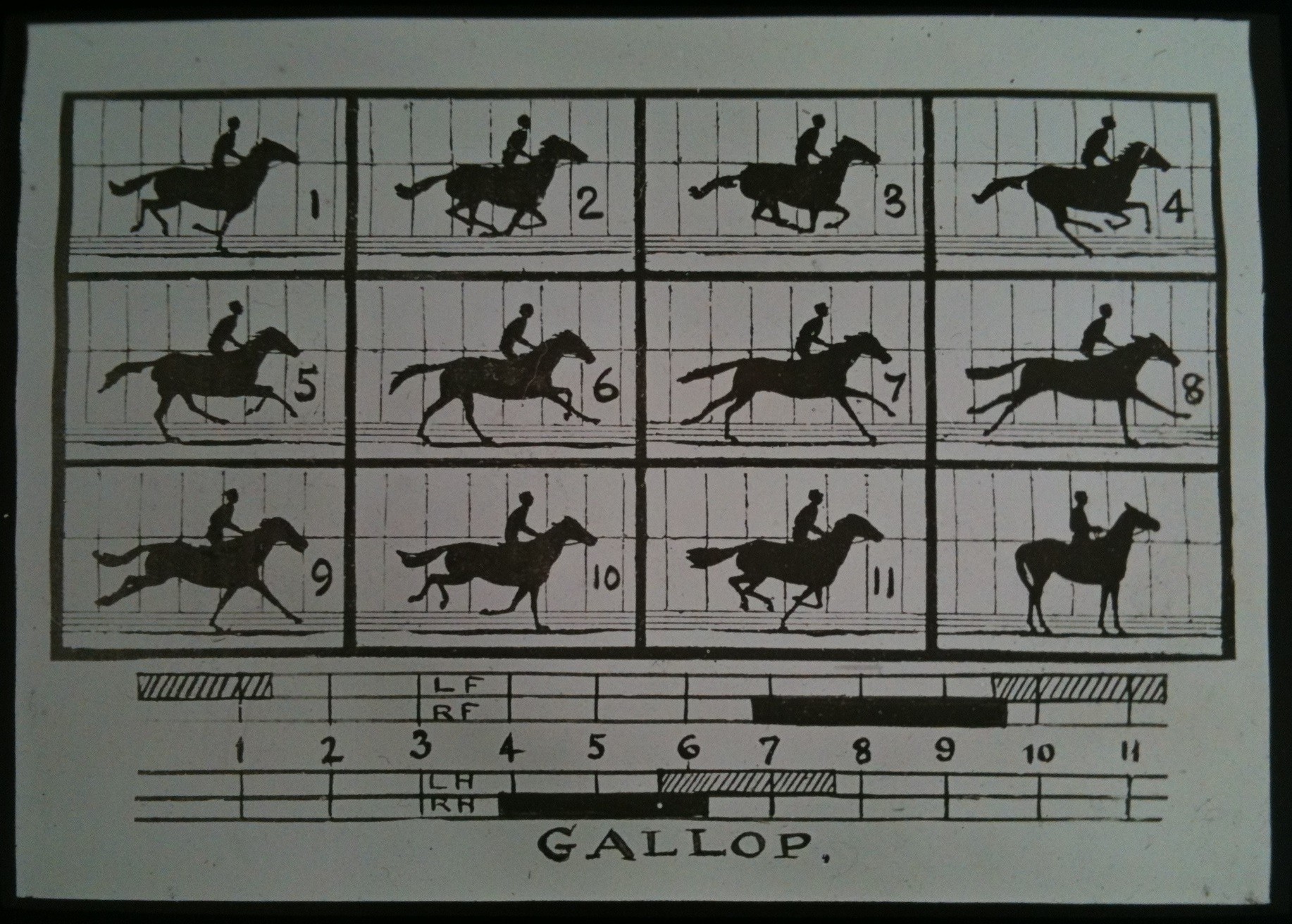

Horse racing and animal genetics go well together since issues of genetic traits and physiology are of interest to both breeders and scientists. These images illustrate the ‘body in motion’ – from Muybridge’s film still of a horse running at a gallop to a race horse in the midst of a fall during a steeplechase – they can illustrate how race horse breeding has developed by being able to compare the points of the horse in the slides.

Looking over the slides I found that they fell into three sub-genres within horse racing :

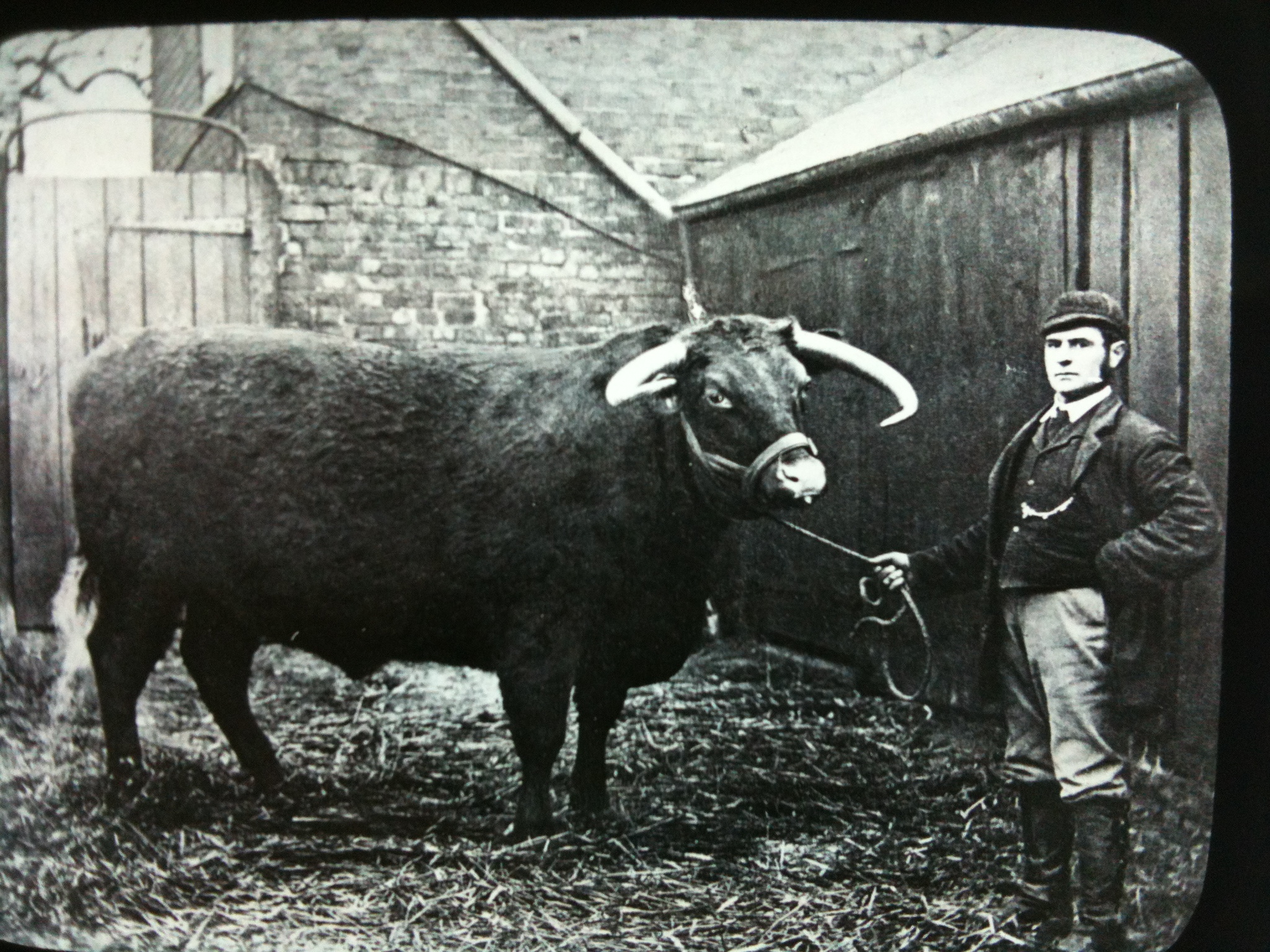

The first, ‘Racehorses at Rest,’ shows various individual well-known horses in profile which is very useful to see and compare favourable traits found in winners. Additionally, the text beneath the image provides a bit of history on the particular horse.

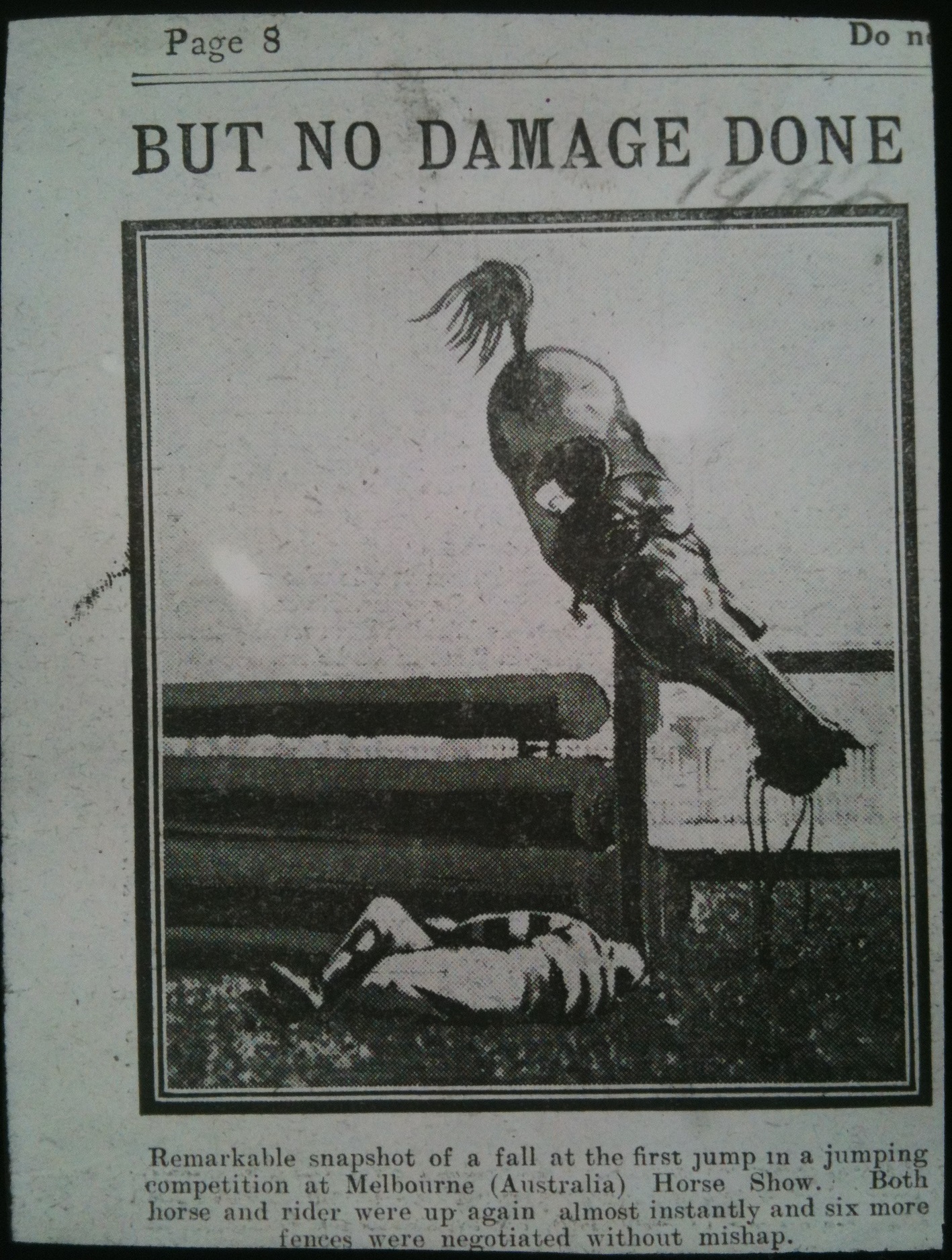

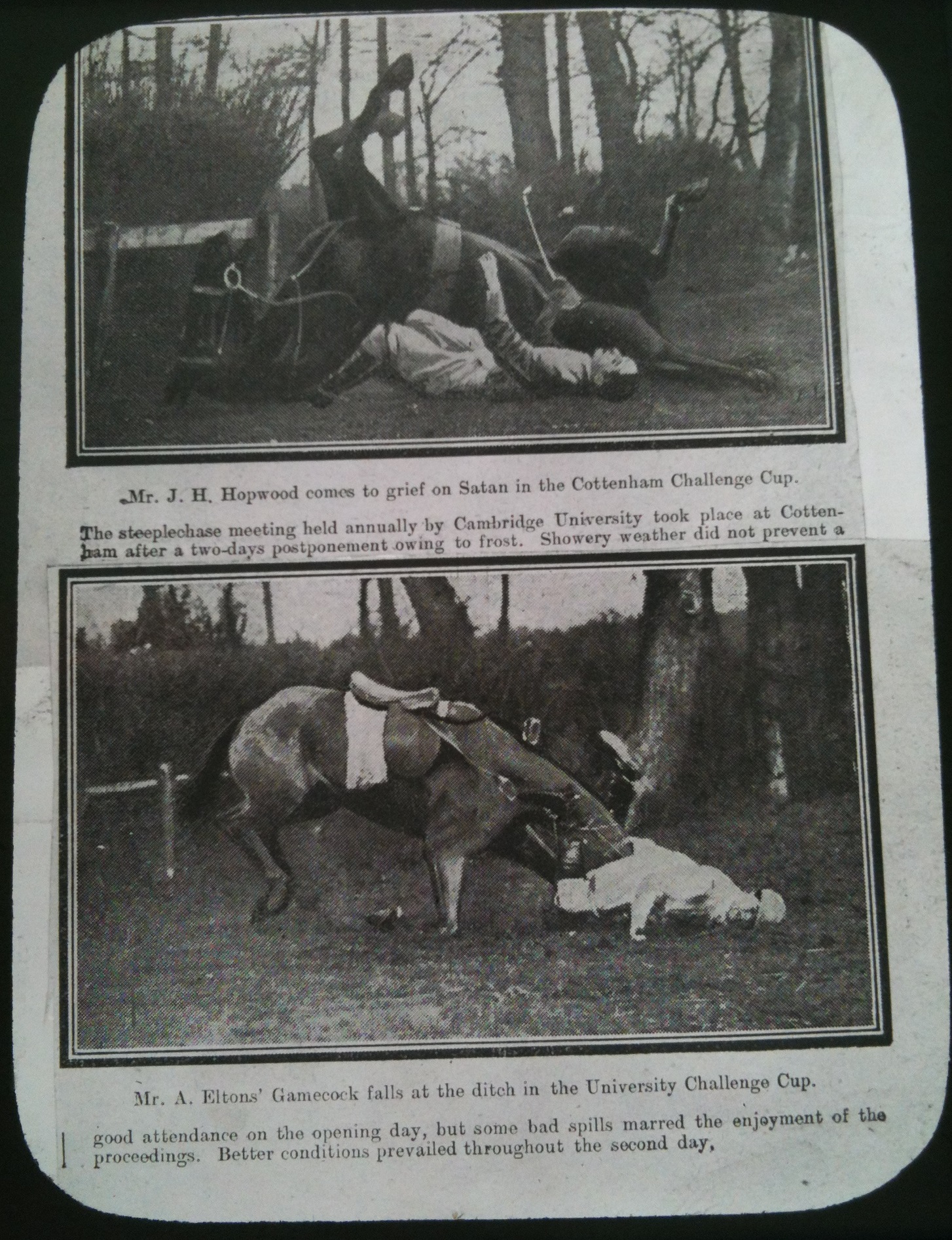

The second, ‘Racehorses during a Race,’ shows the horse and jockey in motion on a flat-track or jumping over fences during steeplechases. These images are very useful to see the physiology of the horse in motion.

The third, ‘Racehorses – Accidents’ – is just that- from showing suffragette, Emily Davison’s pulling down George V’s horse at the Epsom Derby in 1913 to horses falling after taking a jump during a steeplechase. Just as a caution – these particular photographs are not particularly pleasant to view; however, they are fascinating to see how the camera has captured the moment and to see how the horses’ body moves.

Another issue arising is the one on cloning racehorses – can it be done (yes); is it done (yes); are cloned racehorses allowed to race (no); and why clone racehorses (to preserve winning horses genetic lines). Mike Bunker wrote in his article, “Cloning may be Horse Racing’s Next Horizon” on the 2007 Centre of Genetics and Society website,

Although cloning of food animals has become relatively common since 1996, when Scottish scientists made a DNA duplicate of a sheep named Dolly, the notion of copying racehorses for entertainment purposes is a controversial one. The Jockey Club, which writes and enforces thoroughbred racing’s rulebook, and the American Quarter Horse Association both prohibit the practice.

The first horse cloned was “Prometea,” in 2003 by Cesare Galli, at the University of Bologna in Cremona, Italy, though it was considered to be mostly a ‘scientific experiment’; then, in 2005, – the first champion racehorse, “Pieraz2,” was cloned by the same scientist to preserve its genetic lines. In 2008, Charlotte Kearsley (supervised by John Woolliams) wrote her PhD thesis for the University of Edinburgh on Genetic Evaluation of Sport Horses in Britain in which her “aim of this project was to derive models for predicting breeding values for British bred sport horses and hence develop procedures for their evaluation.”

There are more articles and websites on the genetics of breeding and cloning racehorses and there are more slides in the collection as well, so I hope that this has provided some interesting insight!