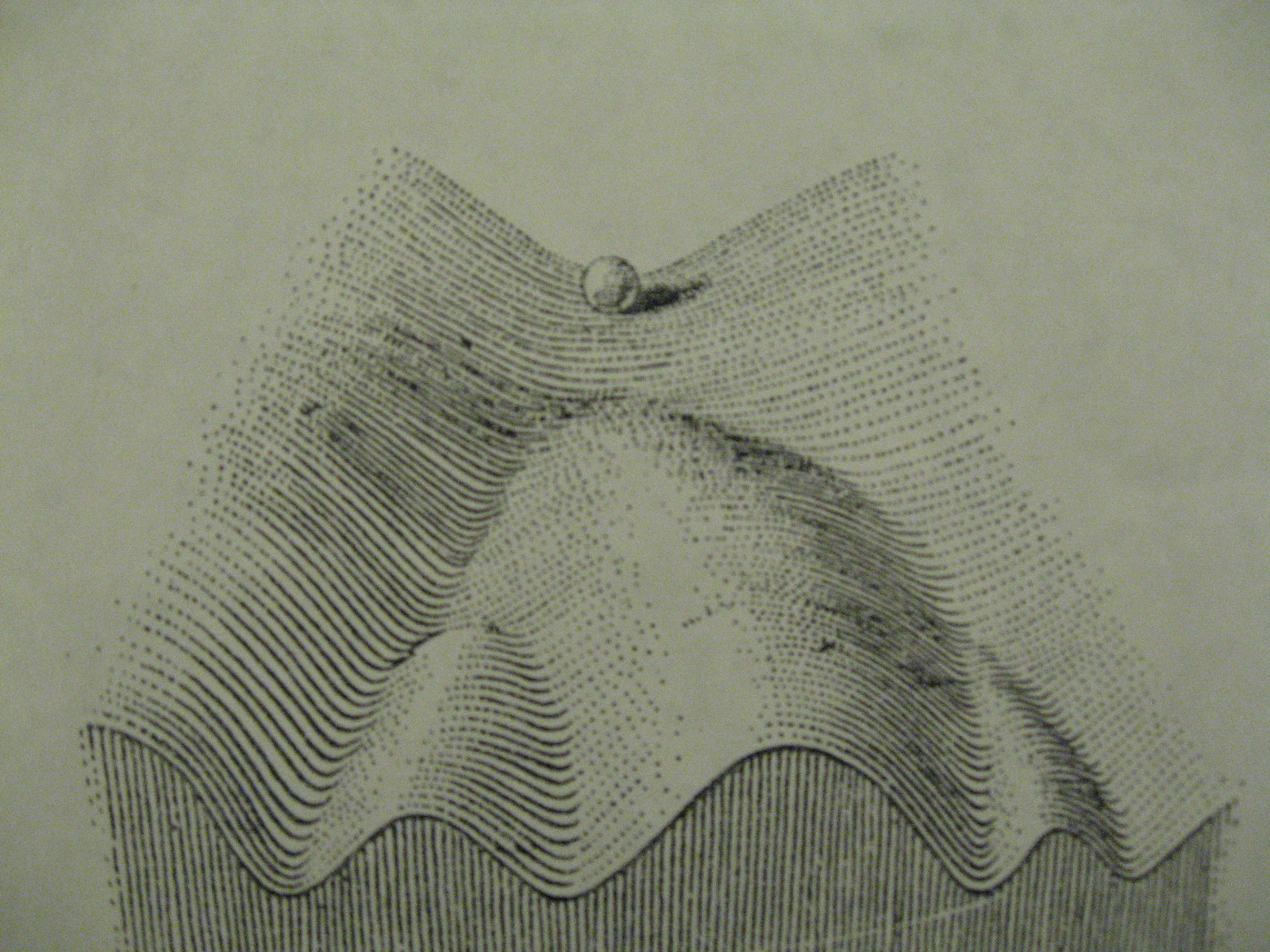

On last week’s blog we looked at a print of C.H Waddington’s epigenetic landscape, part of our collection of diagrams, illustrations and photographs used in Waddington’s publications.

On last week’s blog we looked at a print of C.H Waddington’s epigenetic landscape, part of our collection of diagrams, illustrations and photographs used in Waddington’s publications.

This picture is also from this collection of illustrative material, being one of the original plates and figures used for Waddington’s 1962 book New Patterns in Genetics and Development (Figure 56 in the book). There are 68 figures and 23 plates present in the collection, out of the total 72 figures and 24 plates which appear in the book. The images, mounted on card, bear the stamp of the book’s publisher, Columbia University Press and are marked with symbols and annotations.

The image shows patterns in the wings of the moth Plodia interpunctella, and is used in the book to illustrate a fundamental question posed by Waddington: ‘How is any individual pattern generated?’ Waddington describes what he calls ‘the superposition of several different patterns, which can be recognised as physiologically distinct from one another, either because they are formed at different times during development, or because they react differentially to experimental treatments.’ The image shows ‘a series of adult wings that have been, as it were, frozen in successive stages in the process of pattern formation’. The normal adult wing at a) on the right, while e), for example, shows the result of heat treatment in wild moths (one way by which one can externally disrupt or divert the process of wing pattern formation during development).

The images were returned to Waddington by Columbia University Press in August 1963, along with the original manuscript, which also forms part of the Waddington archive.