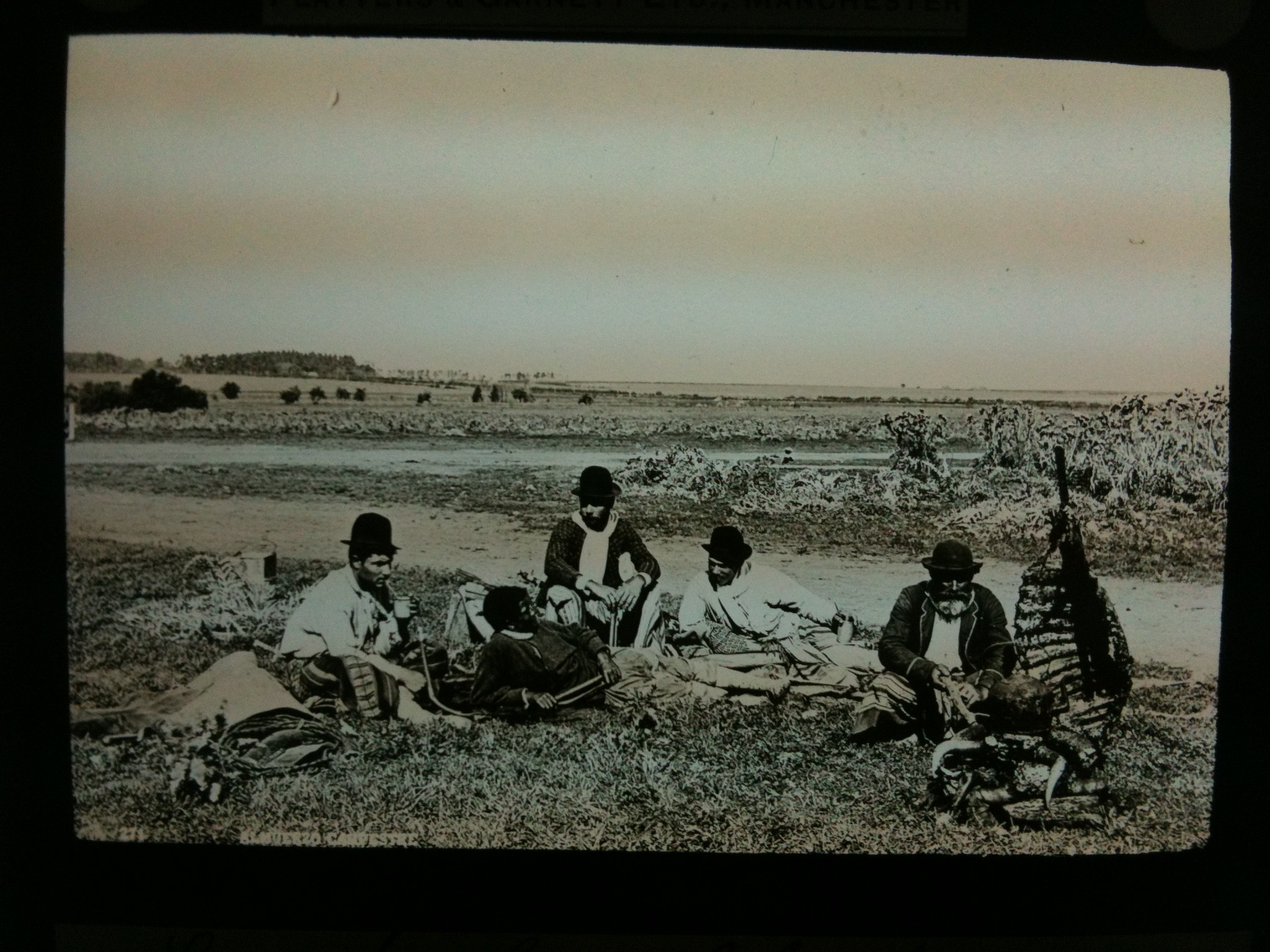

The Karakul is one, if not the, oldest breed of domesticated sheep that originated in Central Asia and is known for its ability to withstand harsh environments.  While the fur pelts of the Karakul were prized, they were also used as a source for milk, meat, tallow and wool. The breed was named for the village, Karakul, which lies in the valley of the Amu Darja River in the former emirate of Bukhara, West Turkestan (now Uzbekistan). This region is one of high altitude with scant desert vegetation and a limited water supply causing the sheep to adapt to the harsh environment.

While the fur pelts of the Karakul were prized, they were also used as a source for milk, meat, tallow and wool. The breed was named for the village, Karakul, which lies in the valley of the Amu Darja River in the former emirate of Bukhara, West Turkestan (now Uzbekistan). This region is one of high altitude with scant desert vegetation and a limited water supply causing the sheep to adapt to the harsh environment.

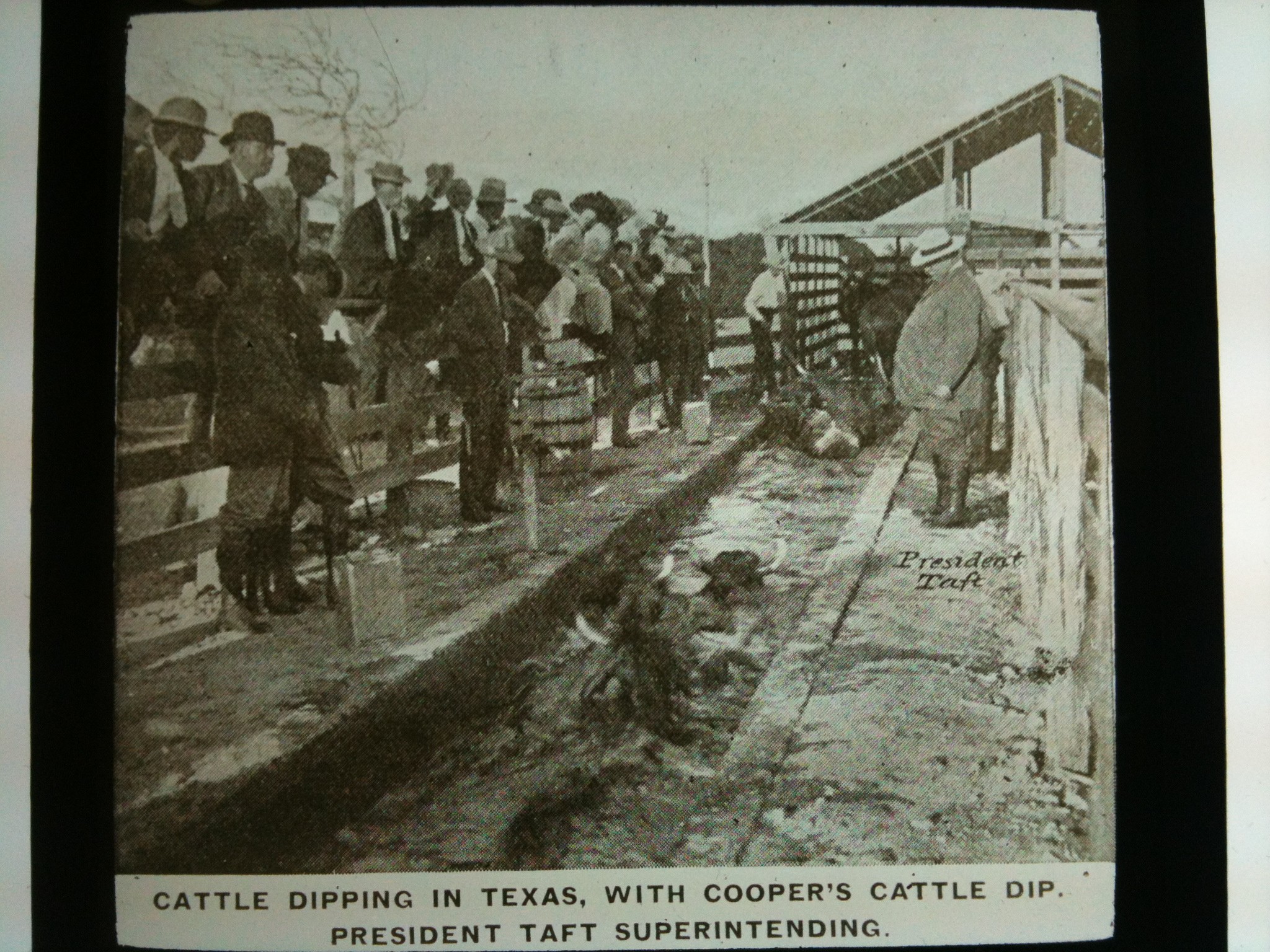

Wanting to introduce this hearty breed of sheep known for the quality of its fur, Dr. CC Young, a Russian physician who immigrated to Texas in the United States, imported the first Karakul rams and ewes into the United States in 1908. From accounts, it was quite an endeavour! After travelling to Russia armed with letters of introduction from President Theodore Roosevelt to prominent Russian businessmen, Young returned to New York City with several Karakul rams and ewes of which the Secretary of Agriculture ordered to be returned to Russia or slaughtered; however, after being in quarantine, they were shipped to his father’s ranch

Wanting to introduce this hearty breed of sheep known for the quality of its fur, Dr. CC Young, a Russian physician who immigrated to Texas in the United States, imported the first Karakul rams and ewes into the United States in 1908. From accounts, it was quite an endeavour! After travelling to Russia armed with letters of introduction from President Theodore Roosevelt to prominent Russian businessmen, Young returned to New York City with several Karakul rams and ewes of which the Secretary of Agriculture ordered to be returned to Russia or slaughtered; however, after being in quarantine, they were shipped to his father’s ranch  in Texas. Then, in 1912, Dr. Young ‘joined the International Sheep Congress in Moscow, Russia and purchased several Karakul rams and ewes from various exhibitors; these sheep arrived in Baltimore, Maryland in 1913, but he had to sell many of them to recoup his finances. He started the Young Karakul Fur Sheep Company with some men in Prince Edward Island, Canada and tried to re-purchase the sheep and move them to the island. Since there was so much interest in this breed of sheep, the company sent Dr. Young to Bukhara to secure a larger flock. He traversed the desert, the southern and central plateaus of Turkestan (Uzbekistan) and along the Amu-Daria River. With his connections to various Russian officials, Dr. Young was able to select the finest specimens and so, a flock of 21 sheep (15 rams and 6 ewes) were shipped to the United States quarantine station in Beltsville, Maryland, where 5 of the rams died and the rest of the flock was shipped to Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island.

in Texas. Then, in 1912, Dr. Young ‘joined the International Sheep Congress in Moscow, Russia and purchased several Karakul rams and ewes from various exhibitors; these sheep arrived in Baltimore, Maryland in 1913, but he had to sell many of them to recoup his finances. He started the Young Karakul Fur Sheep Company with some men in Prince Edward Island, Canada and tried to re-purchase the sheep and move them to the island. Since there was so much interest in this breed of sheep, the company sent Dr. Young to Bukhara to secure a larger flock. He traversed the desert, the southern and central plateaus of Turkestan (Uzbekistan) and along the Amu-Daria River. With his connections to various Russian officials, Dr. Young was able to select the finest specimens and so, a flock of 21 sheep (15 rams and 6 ewes) were shipped to the United States quarantine station in Beltsville, Maryland, where 5 of the rams died and the rest of the flock was shipped to Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island.

Dr. CC Young’s article, “Origin of the Karakul Sheep” in the Journal of Heredity, American Genetic Association is a fascinating first-hand account of his adventures in Central Asia and in his description of the breed.

Dr. CC Young’s article, “Origin of the Karakul Sheep” in the Journal of Heredity, American Genetic Association is a fascinating first-hand account of his adventures in Central Asia and in his description of the breed.