Another theme within the Roslin Glass Slides Collection is physical manifestations of disease and abnormalities in animals from genetic diseases to viral and bacterial infections to insect borne illnesses. Some of the most prevalent in the images are scrapie and scab with some images of Spirillosis in a horse, a double headed calf and cattle meat infected with tuberculosis. Additionally, there are images of animal hospitals and disease prevention methods. This was certainly a vital area of research and interest to these scientists since understanding the genetic aspects of the various diseases could lead to improved treatments and prevention methods to ensure the animals survival and to benefit the economic impact in animal breeding.

Scrapie is a fatal, degenerative disease that affects the nervous systems of sheep and goats. It is one of several transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs), which are related to bovine spongiform encephalopathy.

Scrapie is a fatal, degenerative disease that affects the nervous systems of sheep and goats. It is one of several transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs), which are related to bovine spongiform encephalopathy.

Sheep scab is a highly contagious skin disease caused by a mite called Psoroptes ovis causing scaly lesions to develop on the woolly parts of a sheep’s body making them itch resulting in them rubbing or biting themselves causing wool loss.

Sheep scab is a highly contagious skin disease caused by a mite called Psoroptes ovis causing scaly lesions to develop on the woolly parts of a sheep’s body making them itch resulting in them rubbing or biting themselves causing wool loss.

Spirillosis is a disease caused by the presence of spirilla in the blood or tissues. Spirilla is a ‘genus of large (1.4–1.7 mcm in diameter), rigid, helical, gram-negative bacteria (family Spirillaceae) that are motile by means of bipolar fascicles of flagella. These freshwater organisms are obligately microaerophilic and chemoorganotrophic, possessing a strictly respiratory metabolism; they neither oxidize nor ferment carbohydrates. ‘

Spirillosis is a disease caused by the presence of spirilla in the blood or tissues. Spirilla is a ‘genus of large (1.4–1.7 mcm in diameter), rigid, helical, gram-negative bacteria (family Spirillaceae) that are motile by means of bipolar fascicles of flagella. These freshwater organisms are obligately microaerophilic and chemoorganotrophic, possessing a strictly respiratory metabolism; they neither oxidize nor ferment carbohydrates. ‘

The double-headed Cheviot lamb suffered from Diprosopus or Cranialfacial duplication which is a rare congenital disorder whereby parts (accessories) or all of the face is duplicated on the head.

The double-headed Cheviot lamb suffered from Diprosopus or Cranialfacial duplication which is a rare congenital disorder whereby parts (accessories) or all of the face is duplicated on the head.

Tuberculosis is a common, and in many cases lethal, infectious disease caused by various strains of mycobacteria, usually Mycobacterium tuberculosis which infects the lungs and occasionally other parts of the body.

Tuberculosis is a common, and in many cases lethal, infectious disease caused by various strains of mycobacteria, usually Mycobacterium tuberculosis which infects the lungs and occasionally other parts of the body.

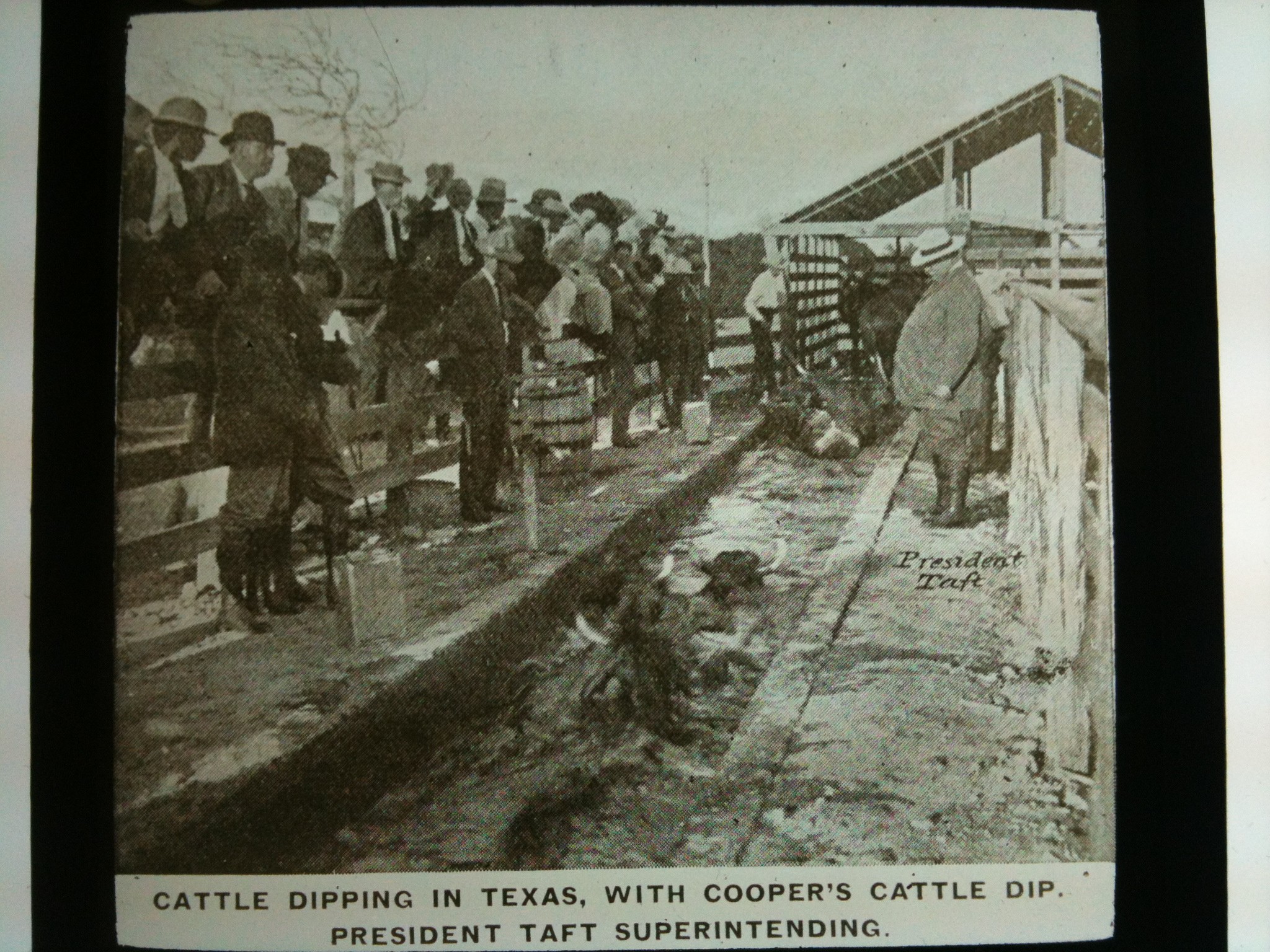

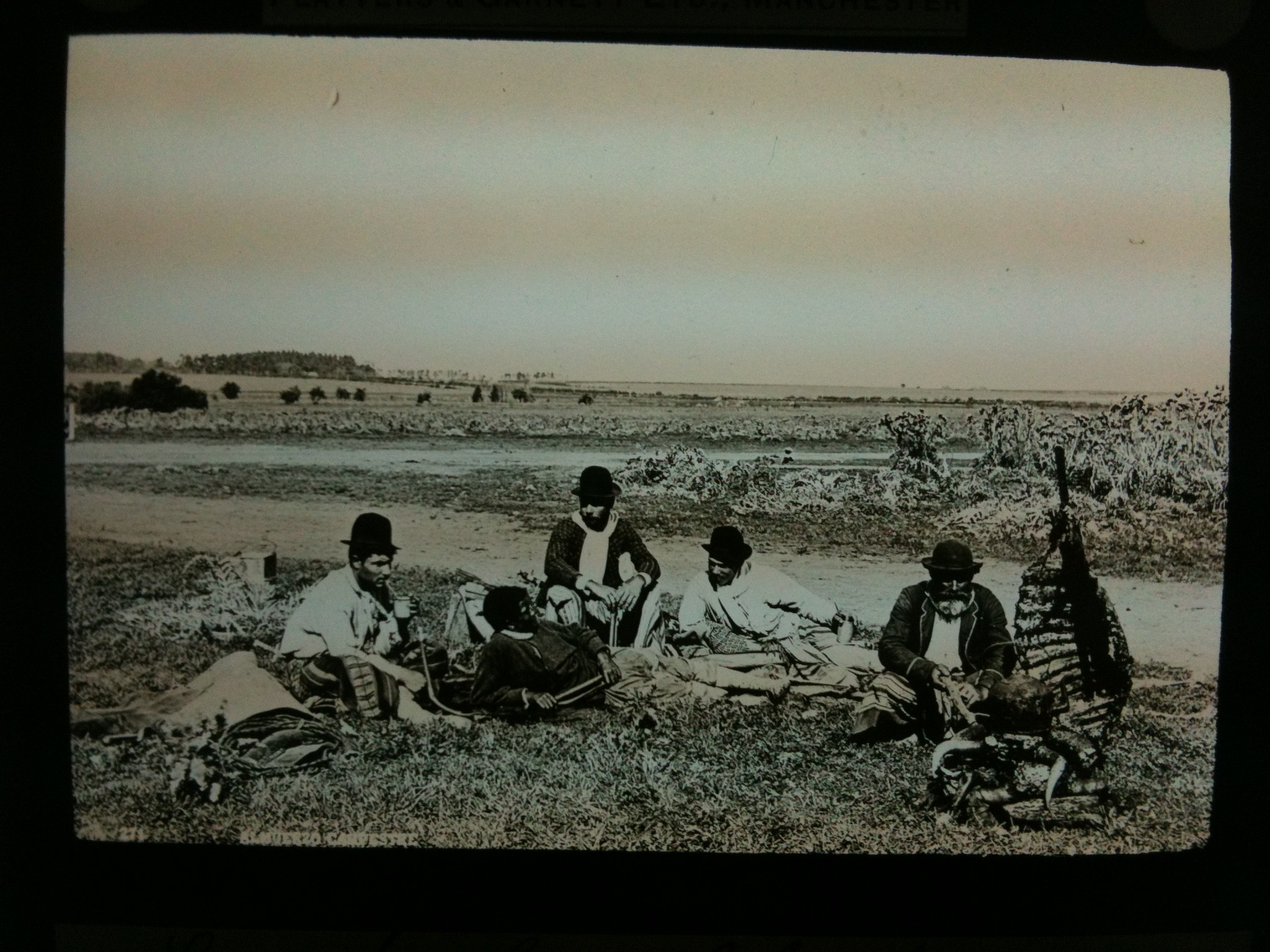

There are also images of disease prevention methods though mostly of cattle dipping to prevent ticks and one of an animal hospital in India.

While I’ve catalogued many scientific off-prints and glass slides on animals and disease in the Roslin Collection which are available for you to see if you make an appointment to see the material, I’d also recommend having a look at the DEFRA website for more information.