Ian MacKenzie: More of a superstar than an object, but very much SSSA.

by Caroline Milligan

From dozens of ideas on my ‘What shall I write about for my SSSA in 70 objects blog post’ mind map I finally chose to share with you this photograph, of Kath Campbell[ii] and Lizzie Angus which I have loved and admired from the moment I first encountered it, which was probably in a Scottish Ethnology 1 lecture in my first year.

When I worked at the School of Scottish Studies (2004-2018) I would give a couple of lectures a year on Fieldwork Practice and this picture was very often the opening image for my PPT presentation. I love ethnology and thank my lucky stars that I found my way to the School as a mature student in 2000 and for me this image encapsulates so much of what I admire about my discipline.

At its very essence, ethnology is a conversation and an opportunity to share community and pass on knowledge that we, as researchers, can collate, interrogate and then describe in order to understand our shared cultural lives. In this photograph, both Kath (ethnomusicologist) and Lizzie (a sprightly 106 year old who had been a pupil of the great north-east song collector, Gavin Greig) are very obviously enjoying their time together: they’re leaning into each other, meeting each other’s gaze, and smiling like a pair of Cheshire cats. This photograph, and the others discussed in this blog post, were created by my fine, much loved and greatly missed colleague, Ian MacKenzie, who was the School’s photographer and photo-archivist for the best part of 25 years.

Ian was a photographer with a splendid eye for detail who created beautiful images across a range of themes. I especially like his portraits. He was a sociable man who loved people, and his photographs are a lasting testimony to that. He also possessed a great ability to notice, successfully photograph and develop images which celebrate and draw attention to distinct textures and details. In this image of Kath and Lizzie, just look at Lizzie’s cardigan, with its heart-shaped pattern, and the heart-shaped pin brooch on her dress. Kath and Lizzie look at each other as if through a mirror: Kath may be seeing the old woman she hopes she will one day be, while Lizzie sees the enthusiasm of youth and, perhaps, a reflection of the young woman who rests inside her own ageing body. I never tire of looking at this photograph, and always I see the sheer joy of sharing knowledge and life stories that is at the heart of many ethnological fieldwork sessions.

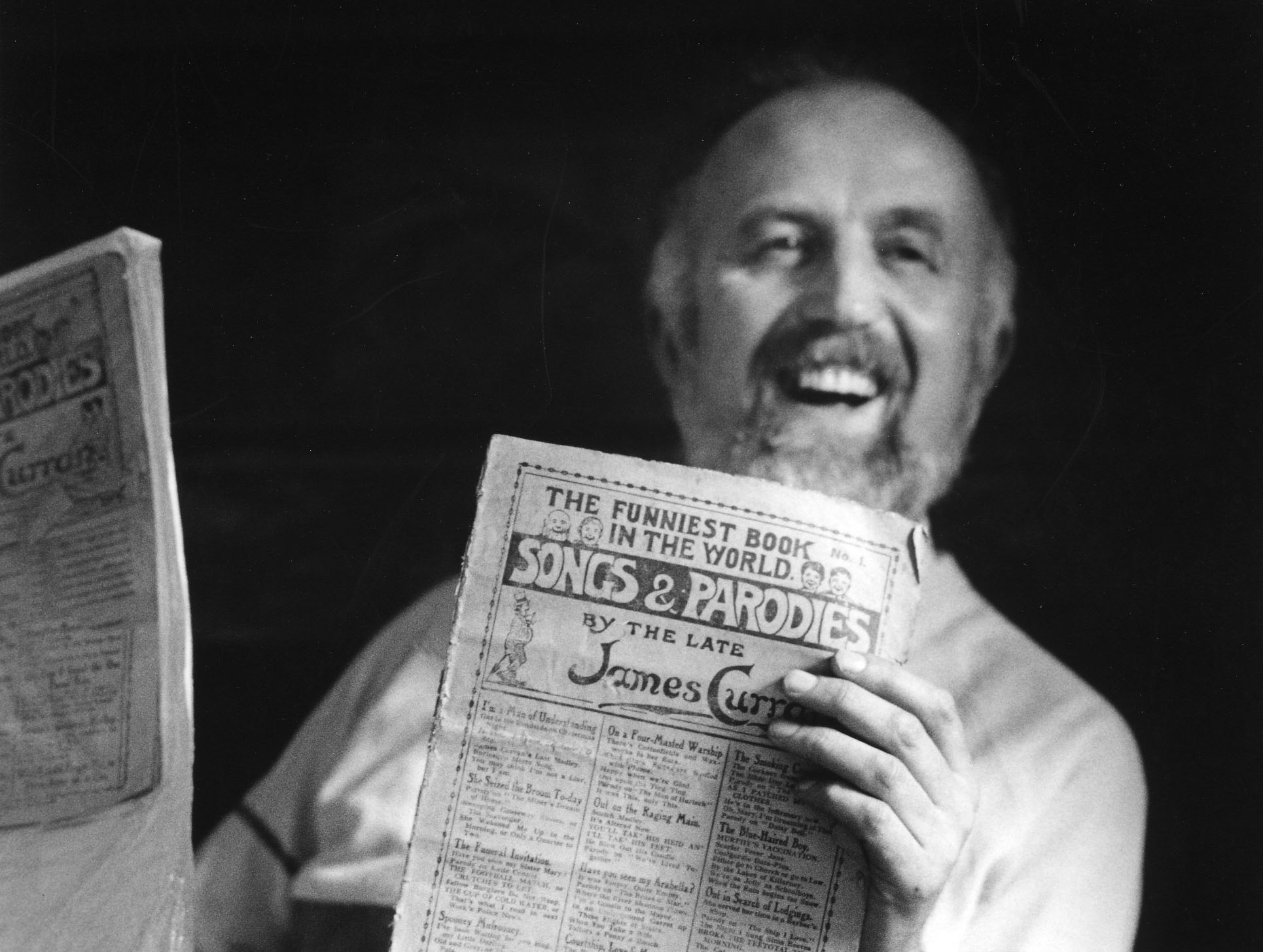

Another portrait by Ian which I adore is this one of singer, songwriter, antiquarian book-seller, teacher, researcher etc. etc.- the splendidly marvellous and multi-talented, Adam McNaughtan. This portrait seems to capture the essence of Adam: his laughing eyes, always with a ready smile, but also self-effacing – he’s almost hiding behind copies of the song-sheets he takes such a delight in. The Songs & Parodies pamphlet he holds, headed ‘The funniest book in the world’ is an entirely fitting choice given Adam’s own song-writing genius when it comes to the comedic – Skyscraper Wean, Cholestoral and Oor Hamlet being particular favourites. This photograph says to me, ‘Life’s a laugh!’, which is exactly the feeling I have whenever I’m in Adam’s company.

For T C Smout, ‘studying photographs [can convey] an untold wealth of detail in social history, and [raise] all sorts of odd questions’.[iv] While the portrait shot of Kath and Lizzie, and the one of Adam, are beautiful in their simplicity, there are other portraits by Ian which work in a very different way, with settings which can be read like a book. For Ian, this was clearly no happenchance. The settings are deliberately recorded so that we can read and understand the people being photographed, as well as the time, place and space they inhabit.

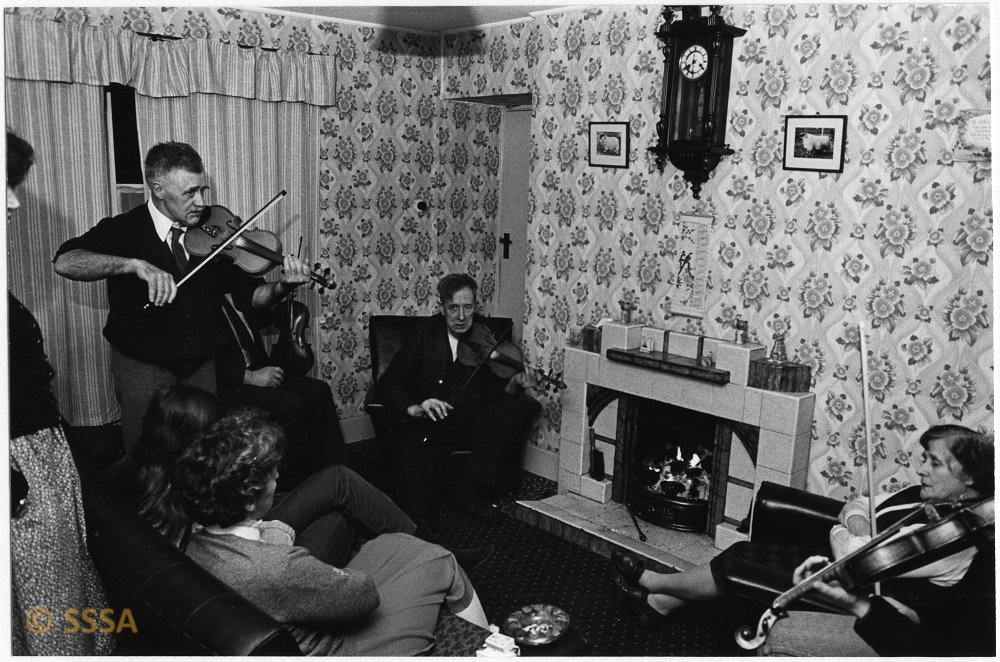

One example of this is Music in the Home, Forrest Glen, Dalry, Galloway, 1985. To my mind, Ian leaves us in no doubt that the seated musician in the middle of the photograph is the most important person in the room. All the others in the photograph seem to look and lean towards him. Although seated, your eyes go first to him, rather than the standing fiddle player to his left, or any of the other figures on the periphery. There’s a stillness and reverence to the gathering: the only hands visible belong to the musicians, the curtains are drawn over: this is all about the music. I also love the textures in this photograph and can readily conjure to mind how the cold tiles on the fire surround, or the textured pattern of the wallpaper, would feel to the touch. This textural richness is something I think Ian worked hard to reveal when he made his photographic prints.

The craft and skill of Ian as a photographic developer and printer is clear in this image. I well remember visiting Ian in his warren of rooms in the basement at 27-29 George Square.[vi] His darkroom, especially the lingering chemical smells, reminded me of evenings spent at the Street Level gallery darkrooms in Glasgow, painstakingly practicing the nuances required in producing photographic prints from my negatives. I remained pretty much a novice, but I remember the thrill of producing a print which I could be proud of and which reflected the nuances of the image I wanted to reveal. I believe working in the darkroom would have been a particularly immersive and rewarding aspect of Ian’s creative practice and this is evident in the subtle precision he consistently managed to achieve in his work.

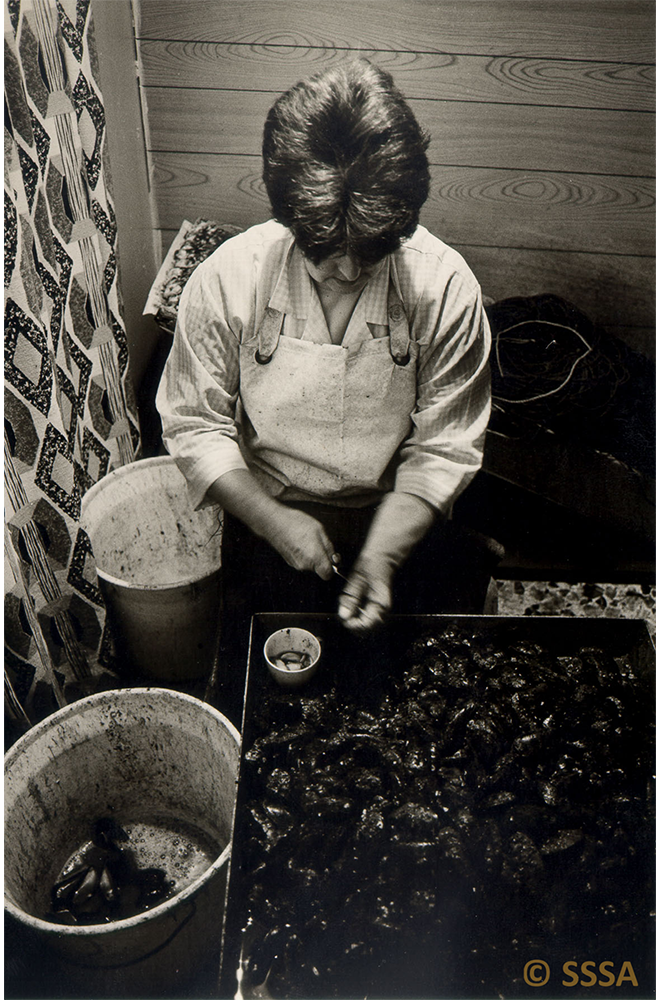

A series of photographs which illustrate Ian’s skills as an ethnologist and his eye for texture and detail are those he made of the Gourdon fishers. In contrast to the images discussed so far, these photographs were created in a much more dynamic setting. In my chosen image, the woman baiting the fishing lines for the next launch hasn’t time to look up: she’ll be racing to get the baited nets ready in time for the next launch and taking her eyes off the task in hand looks likely to result in injury. Her fingers are working more quickly than the camera shutter and her surroundings are entirely functional and efficient. You can tell at a glance that this is tough, cold, dirty, smelly work and way too important to be paused for a mere photograph. Again, I love the contrasting textures: the startling gleam of the mass of baited fishing line in the tray, the stained buckets, the wall and doorway coverings. We can glimpse a small table and chair in the background, maybe to allow for a short rest if work is going well and there’s time for a 5 minute breather.

This image is one which allows us to appreciate how Ian brings a painter’s eye to his photographic work. Like Vermeer’s, The Lacemaker, this photograph contains everything we need to see so that we can understand what is essential: in this instance about both the baiter and the bait-netting task.

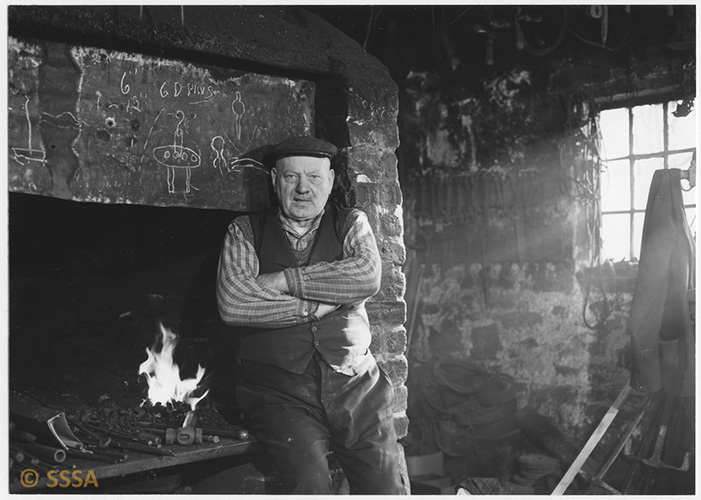

The next photograph is another work-related one. The photographs of Kit Sked, taken in 1987, are perhaps some of the most well-known of Ian’s ethnological portraits. Kit was the fourth generation of the Sked family to work as blacksmith at the Cousland Smiddy, and, when this series of photographs were made, he had recently announced his retirement. With no-one yet identified as his successor, one wonders what Kit’s thoughts were during this session or when he is moving around the workshop.[viii]

Again, we’re in a functional work-space, one that has not changed for perhaps hundreds of years. However, unlike the previous image, this space has a feeling of permanence. This is Kit’s domain. There’s a strong feeling of ‘a place for everything and everything has a place’ about the smiddy. A space that is as much part of the man as the man is part of the space. Like the fish-baiting station, the space is functional and work-ready: the fire is going strong, tools laid out, strong sunlight streams through the window and Kit’s jacket hangs such that we can believe it hangs in that exact place every working day. This time Kit meets our gaze square on. I love his clothing and the precision of the light and the way this falls into the room and over the left side of Kit’s body. Again, this image, like many created by Ian, is like a painting and can be looked at, considered and enjoyed time and time again. The surface of the brickwork, Kit’s shirt, the chalk markings on the fireplace lintel and the wide array of tools (what are they for?), all merit closer attention, yet all of it can also be appreciated and enjoyed in a single glance. Yes, Ian has left us an impressive body of work, but he also left us too soon.

I remember the occasion of Ian’s final resting which took place at Inerinate, Kintail in February 2010 on a cold, clear, bright-blue day. I recall feeling so angry that such a lovely man should be taken so early and of being quite overwhelmed by the sad truth of this. But I also remember feeling happy that so many lovely people had been brought north, to be together, by their love of the man. There was a real sense of joy on that day. Ian was a simple-living, funny, warm man who loved life. He told me more than once that there were few things in life as good as discovering that the pear you had just bitten into was at the absolutely perfect moment of ripeness for eating. This about sums up Ian’s approach to life and the joy he found in it. He lived a very good, albeit far too short, life and I remember him fondly for his humanity, humour, generosity of spirit and for his great artistry and craftsmanship and the wonderful legacy he has left within the cabinets and catalogues of the SSSA photographic archive.

It has been a pleasure to choose Ian as my ‘favourite object’ from the SSSA collection and to have the excuse to set aside a little time to spend in his company and renew our friendship. It feels like he’s given me the gift of some of his quiet joy in return and I think he’d be chuffed (if a little abashed) to be called to mind and remembered by us.

Grateful thanks to Louise Scollay for helping me with the images and photograph credits for a number of items included in this blogpost.

Caroline Milligan, July 2021

All Images by Ian MacKenzie, © The School of Scottish Studies Archives.

[i] Dr Katherine Campbell and Lizzie Angus, Ythanvale Nursing Home, Ellon (Aberdeenshire), 2000

[ii] Dr Katherine Campbell was ethnomusicologist at the School for a number of years and worked on the Greig-Duncan song collection with Dr Emily Lyle.

[iii] Adam McNaughtan – song book, 1989

[iv] To See Ourselves, Dorothy I Kidd, with preface by T C Smout, NMS 1996

[v] NII/8a/8774. Neg. A6/228/19. 6 December 1985. Gathering of Galloway musicians in the house of Robbie Murray at Nether Forrest, Forrest Glen, Dalry, Glenkens, Galloway, From L to R: Alyne Jones, Davy Jardine and Robbie Murray. Evening recorded by Jo Millar.

[vi] Ian wrote to me in 2008, when he was coming back to work after a long period of ill health and he thanked me particularly ‘for keeping the place [his archive] company’. Re-reading this letter, I smile at that line, remembering again the quiet calm of the photographic archive, the back door often open to the garden, the little zen garden on the wide windowsill, the frequent stream of people seeking Ian out for guidance, discussion and good company. He was very much part of that space, as it was very much part of him.

[vii] BIII6c1/8599

[viii] The smiddy had been in Kit’s family continuously since 1882. Kit had announced his intention to retire in 1986, and then retired in 1989).

[ix] BVIII/7/g1/8782

[x] Collage image by Colin Gateley using one of Ian’s self-portraits.

Caroline Milligan is Archives Assistant with the Regional Ethnologies of Scotland Project, at Centre for Research Collections. She is also Research Assistant, within the European Ethnological Research Centre, University of Edinburgh.