Wet Monday, Henry VIII Falls in the River, and the Ogre of Smeeth, all funded through the Bank of Sweets.

For our fifth visit to the ECA Illustration students’ Notgeld project we enter the world of myth and legend. Many of the German towns used local legends to illustrate their Notgeld, and several of the students went the same way.

Monika Staachowiak:

For my notgeld project I was inspired by Polish traditions and folklore.

The first notgeld with domination 10pln represents – Lajkonik.

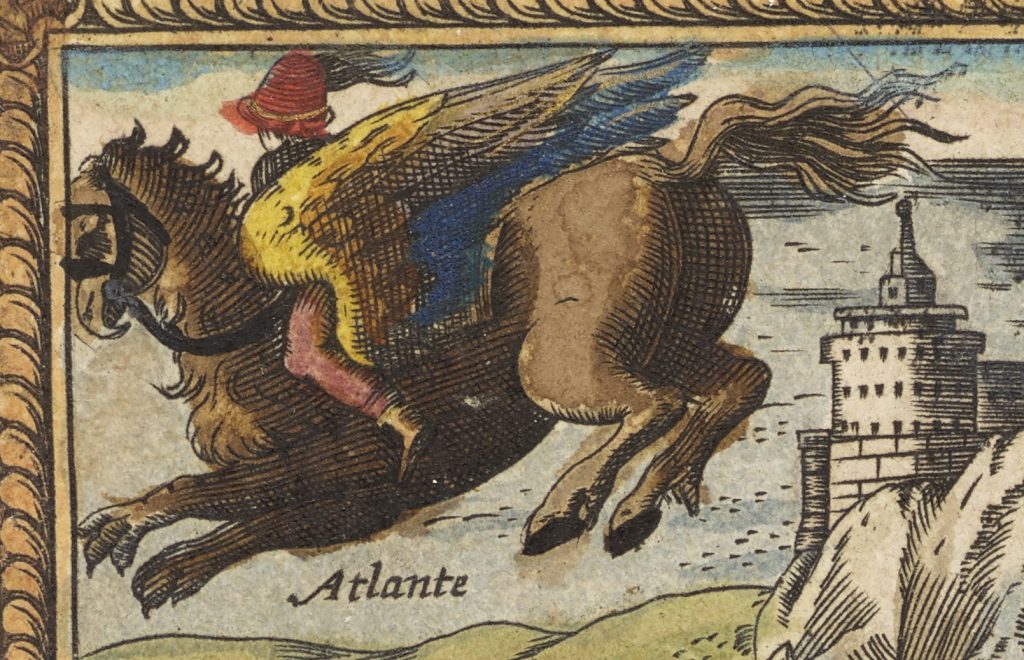

The Lajkonik is one of the unofficial symbols of the city of Kraków, Poland. It is represented as a bearded man resembling a Tatar in a characteristic pointed hat, dressed in Mongol attire, with a wooden horse around his waist (hobby horse). It is the subject of the Lajkonik Festival that takes place each year on the first Thursday after the religious holiday of Corpus Christi. Integral part of the celebration is a great street parade. It demonstrates the victory of Krakow’s residents over the Tatars.

The second notgeld with domination 20pln represents Śmigus-dyngus also known as lany poniedzialek, meaning “Wet Monday” in Polish.

It is celebrated on the first Monday after Easter, and the way to celebrate is actually really fun: you need to pour water on other people.

Traditionally, the boys need to pour water over girls, and they also need to spank them with pussy willow branches, and girls do the same to boys. It is believed that the girl that is most wet or the one that received most amounts of water, has more chances to get married.

The third notgeld with domination 50pln is representing – Masqueraders (carolers).

In the Polish tradition, during the Christmas period, carollers dressed up and walked in the villages from house to house with wishes of prosperity in the New Year. The carolling group wore mascarons, which was often accompanied by comic and frightening scenes and performing various kinds of pranks to spectators. The whole spectacle was accompanied by the atmosphere of general cheerfulness.

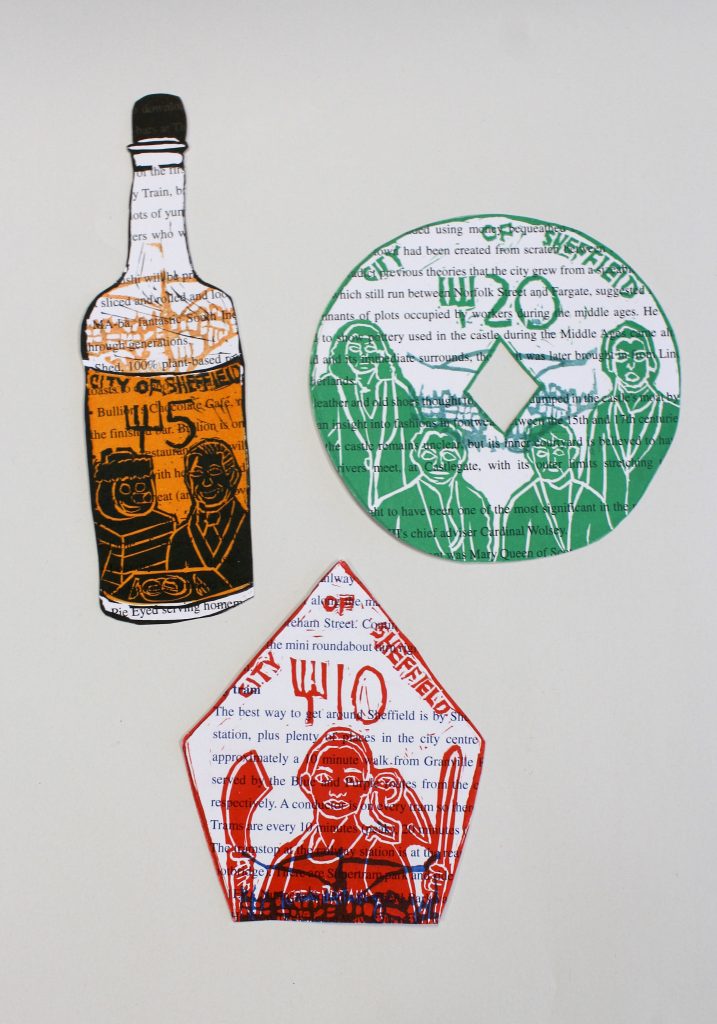

Polish folklore. Monika Stachowiak

Petra Wonham:

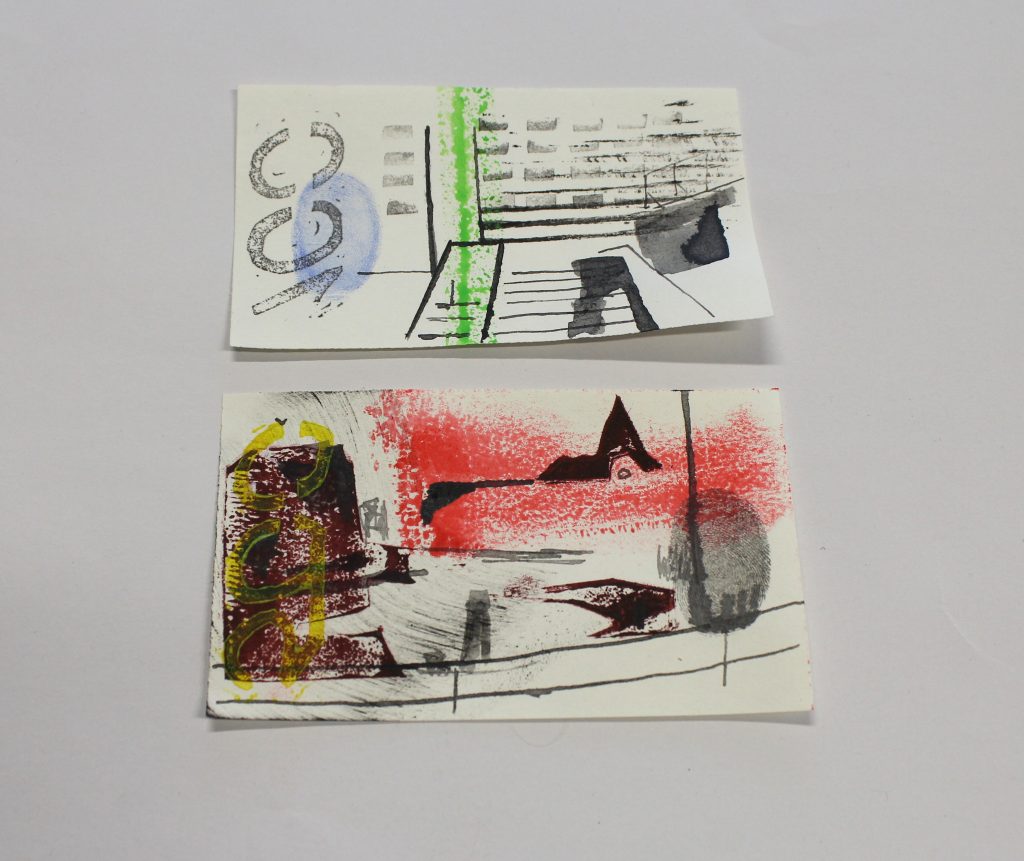

My Notgeld notes are based on tales of King Henry Vlll in Tudor Hitchin, I have used a variety of techniques to print them such as lino, riso and letterpress, and I have kept to a simple colour palette. The denominations are based on money used in Tudor times.

[Henry VIII used to hunt in the countryside around Hitchin. The Notgeld illustrates the local tale that he fell in the river – either because he tried to vault over it and his pole broke, or he fell off his horse during the chase]

King Henry VIII visits Hitchen, Hertfordshire. Petra Wonham.

Tiggy Wilkes:

Designs inspired by folk tales and superstitions from my home county, Norfolk. The Black Shuck, a werewolf who roamed the coast, The Pedlar of Swaffham who dreamt he found treasure in his garden, and The Ogre of Smeeth who occupied a forest for many years until he was slayed. I created them in an old 18th century style, as if they were warnings and tales to inform the locals at the time.

Created using letterpress and lino relief printing.

Norfolk folklore. Tiggy Wilkes

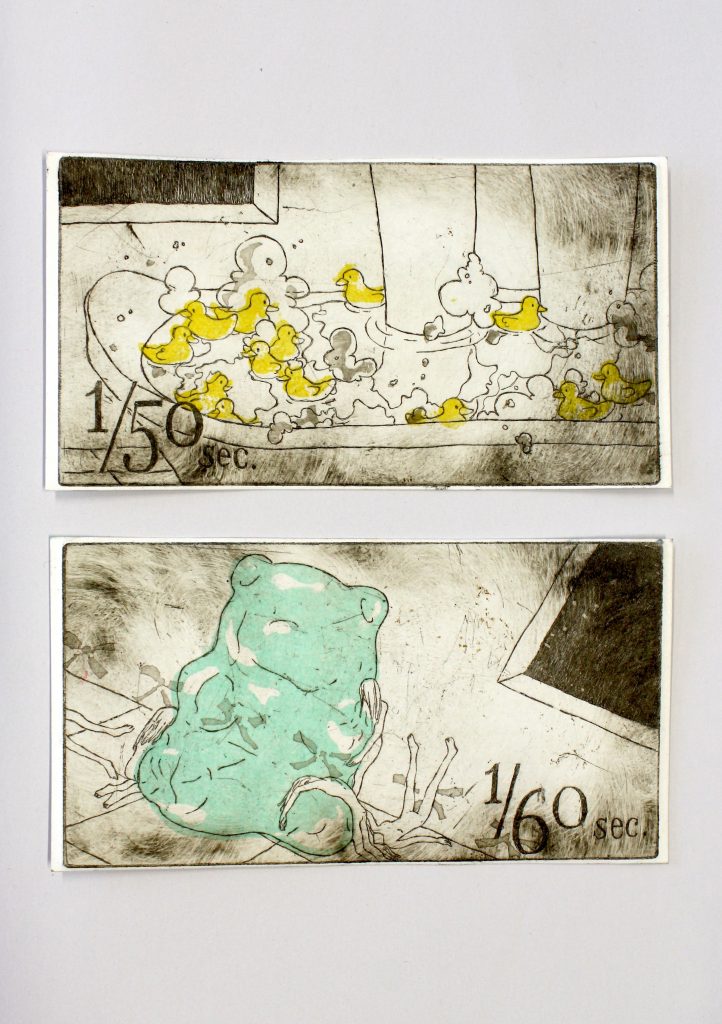

Our apologies for including this final entry in this post, where it seems not to belong. We had hoped to pay more attention to examples of Notgeld using interesting units of currency. In post World-War I Germany some Notgeld was produced in unusual materials, including compressed coal dust, and many of the students thought about their currencies very carefully. You may have noticed Zhaoyang Chen’s Bank of Rabiland, in a previous post, counted in ‘Caro[t]s’, Naiomi Sun’s Utopian money is issued in units of time, and Rosie Cockrell’s Sheffield runs on units of forks. We thought that Zoe Zhou’s Bank of Sweets took the biscuit!

Zoe Zhou

For me this project is characteristic of time which reminds me of my childhood. In the set every note is quite different because I tried to show different side of that period. One of them is about the lovely children having sweets, rather than money, I believe sweets are valued by them. The other two are about my hometown and my favourite place to go with my parents, the aquarium.

Bank of Sweets. Zoe Zhou