Satire

This is the second in our series of posts based on the current exhibition in the Library Gallery, and the project by Edinburgh College of Art Illustration students, based on the album of Notgeld, emergency money, from the early 1920s.

Some of the original German Notgeld was satirical, containing harsh commentary on the world which created it. One of the students picked up on this idea, and produced a set of notes commenting on current U.S. politics. Rachel’s puns on the names of politicians, her comment the state of the economy and political institutions are all completely in the spirit of the satire used on the original Notgeld. What she did not know was that one of the other items in the exhibition contains satire just as biting, but four hundred years older.

Rachel Berman: Politics and Hyperinflation

“The starting point for my project bloomed from two persistent themes within the presentation of the authentic Notgeld: Politics and Hyperinflation.

Indeed, as an avid political cartoonist, I was intrigued by these notions and was compelled to apply these elements to the contemporary context.

For this, I imagined a near dystopian futuristic USA (2019 to be precise), in which our current Supreme Leader has rewritten the course of history by converting the US Dollar to the US Donald. This rookie mistake has resulted in extreme hyperinflation, to the point where 1 Dollar now equates to 100 Donalds.

Furthermore, our Leader-in-Chief has decided to rename the US Penny, the US Pence (after his Vice President Mike Pence) and the US Nickel, the US Kavanickel (after his newly appointed Supreme Court Justice).

Additionally I have played around with several details on each note/bill.

For the Donald, I have altered the numbers to read 007, a reference to James Bond, with whom the President believes he shares a likeness.

For the Pence, I have swapped the ‘United States Federal Reserve System’ with the ‘National Rifle Association’, as the latter bared a strong resemblance with the former and better depicted Mr. Pence’s values.

Finally, for the Kavanickel, I wanted to have this used as a legal acquittal for all ‘past’ offences. For this I modelled the colours after the Monopoly ‘Get out of Jail Free’ card. It is no secret that Judge K’s past has been tainted by many credible allegations of sexual assaults. Despite this, however, he, like many other white men, has managed to evade the consequences of his crimes. I wanted to pay particular attention to this white male privilege and illustrate this section of society’s entitlement mentality.

In conclusion, I added a cheeky ‘Made in China’ label to hone in on the blatant fact that our industries are being overrun by the Chinese government, and that despite Trump’s rhetoric, we are NOT number one.”

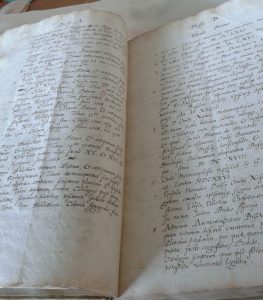

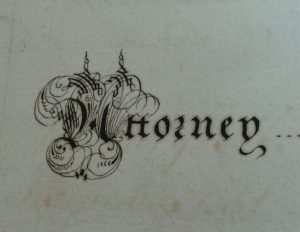

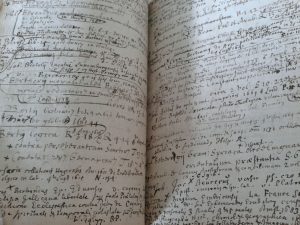

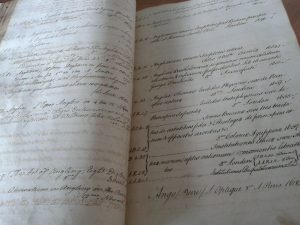

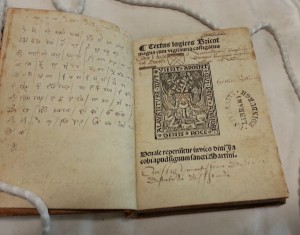

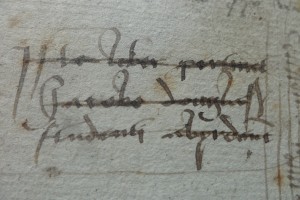

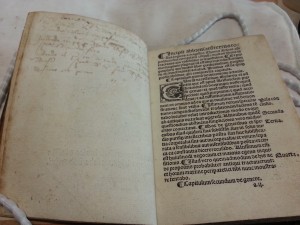

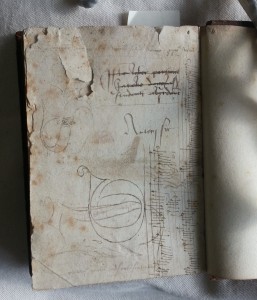

There is another piece of trenchant satire in the exhibition; Robert Parsons’ (sometimes known as Persons) response to the edict of Queen Elizabeth I against the Catholics of England (Cum responsione ad singula capita… Elizabethae, Angliae Reginae, haeresim Calvinam propugnantis, saevissimum in Catholicos sui regni edictum, 1592).

This has much in common with Rachel’s Notgeld, and much of contemporary political satire. Firstly it was calculated to gain the maximum circulation, in this case by being written in Latin and published in several European centres simultaneously. Latin was then the language for international communication, much as English is today, while the modern means of gaining wide coverage is, of course, to publish online. Parsons’ satire gains its effect by using all the techniques of argument which were appreciated in the sixteenth-century; complex formal rhetoric, references to classical literature and the Bible, and contemporary ideas of the ridiculous. The modern equivalents are the punning jokes, references to contemporary popular culture and vivid images, which Rachel exploits to the full.

The background to Parsons’ book is the attempted invasion of England by the Spanish Armada in 1588. In the aftermath a proclamation was issued by the English crown, though actually written by the Lord Treasurer, Lord Burghley, accusing English Catholics of being in league with the Spanish against the English state, and English Catholics living abroad as being dissolute criminals. The response was a co-ordinated and sophisticated series of publications from the English Jesuits in Europe, culminating in this.

Parsons avoids attacking the Queen herself, concentrating instead on the ministers who were responsible for the legislation. His style is to make them ridiculous, by interpreting their actions and beliefs as monstrous and re-telling events to make them preposterous (according to some modern commentators his was a more truthful account than the official English version of the story). He points out the ministers’ extra-marital affairs and controversial religious views, as making them unfit to legislate on religious matters. He compares them to evil politicians from English and Biblical history. This is a very similar approach to Rachel’s satire of contemporary politics, with the exception that it depends on words, rather than images, for its impact. We live in a much more visual world than the Elizabethans did: easily-transmitted film and photographs give the modern satirist possibilities for visual jokes which depend on the audience recognising the victim. Rachel exploits this to the full in her Notgeld, but it was something which was not open to Robert Parsons.