The Library holds a very rich collection of the records of its own activities, stretching right back to the charter of Clement Littil’s bequest in 1580, which started the library. Many of the books acquired at every period since then are still here, often bearing physical evidence of their history in the collections, in the form of inscriptions, old shelf marks, or bindings distinctive of a particular period. The records and the books have the potential to be a very rich source of information and useful to researchers in many different subjects, but currently they are poorly understood and documented and are very difficult to use.

This summer we welcome to CRC Nathalie Bertaud, an Employ.Ed intern, who is working on the records of the first two and half centuries, or thereabouts, of the library’s history, producing a research guide and collecting the data to improve the descriptions of the records on the catalogue of the University Archives. She has been making many discoveries:

Ever wonder how long a book or other object has been in the library and where it comes from? How much it cost or by whom it was given to the library? Or still, what the money given by students was spent on? With a good number of early press, subject and author catalogues, as well as matriculation and donation books, the history of the University’s library is not so dark a place to delve in. As we embrace these early records and their flimsy pages and characteristic smell, let us dive into the library’s history and follow, record after record, the life of its marvels.

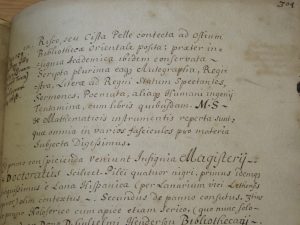

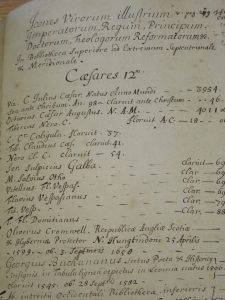

The library has, from very early on, been a welcoming home to objects other than books. This can be seen in items Da.1.18 and 19, as both contain several lists of wonders and curiosities. We are indeed told that precious items were kept in a chest – a sort of 17th century equivalent to our fire-safe! Among the items precious enough to go in the chest were the Bohemian Protest, the marriage contract between Mary Queen of Scots and Francis Dauphin of France, and a thistle banner printed on satin 1640 being found carelessly put in one of Mr Nairn’s books. What is more, a list is given us of portraits that were hung in the library, a celebration of illustrious men and women. Featured celebrities included Tiberius Claudius, Martin Luther, and Mary Queen of Scots. We still do hold some of these portraits. Items related to the discipline of anatomy were also gifted to the library, and we are told in several lists that these comprised the ‘skeleton of a French man’, or a ‘gravel stone (…) cut out of the bladder of Colonel Ruthven’, who, we are informed in Da.1.31, ‘lived six weeks thereafter’.

The library has, from very early on, been a welcoming home to objects other than books. This can be seen in items Da.1.18 and 19, as both contain several lists of wonders and curiosities. We are indeed told that precious items were kept in a chest – a sort of 17th century equivalent to our fire-safe! Among the items precious enough to go in the chest were the Bohemian Protest, the marriage contract between Mary Queen of Scots and Francis Dauphin of France, and a thistle banner printed on satin 1640 being found carelessly put in one of Mr Nairn’s books. What is more, a list is given us of portraits that were hung in the library, a celebration of illustrious men and women. Featured celebrities included Tiberius Claudius, Martin Luther, and Mary Queen of Scots. We still do hold some of these portraits. Items related to the discipline of anatomy were also gifted to the library, and we are told in several lists that these comprised the ‘skeleton of a French man’, or a ‘gravel stone (…) cut out of the bladder of Colonel Ruthven’, who, we are informed in Da.1.31, ‘lived six weeks thereafter’.

Now, where did the books and objects come from? Well, we know a fair amount about key benefactors of the library, as their names are listed over and over again, their generosity being commemorated by several library keepers. Such examples of commemorative lists can be found in Da.1.18 and 19, where the first page lists such generous men as Clement Litil, William Drummond or James Nairn.

Item Da.1.31, a book of donations started by the librarian William Henderson in the late 17th century, gives us short descriptions of benefactors, such as: ‘Isobell Mitchell, at the time of her decease which was upon the 19th of October 1667 left to the college as a token of her great love to the flourishing of piety and good learning the sum of a hundred merks Scots’. Yet, less renowned people also made a contribution to the library’s collection, and when we chance upon a brief description of these almost anonymous benefactors, we get a sense of how collections get built. Such an example is: ‘By Mr David Ferguson, student in Kirkcaldy, a youth of great hopes but was snatched away by an early death (…) a manuscript rare for the writing’, or ‘George Bosman book-seller, gave in the Breviary of the B. Virgin, a manuscript very curiously written & adorned with rich colours besides many exquisite pictures’, or still ‘Mr John MacGregory, student, gave in a Hebrew Bible’.

As lists of new accessions are fairly well represented in the records, we are also offered insight into what places were hubs for book purchasing in the 17th and 18th centuries. London and Holland seem to have been such places, as they are mentioned regularly, for instance in Da.1.32 and 34. The cost of the books purchased is sometimes given as well, and we quickly understand, from looking at the records, that books were purchased not only from donations but also from student fees. However, the money paid by the students was not always used for the purchase of books. We get a glimpse into the day-to-day management of the library when we run through items Da.1.32, 34 or 43, where we can read that money was spent on fees for services rendered, such as ‘for drink money for bringing in books gifted to the library’, ‘for washing 12 pictures’ or ‘for cleaning the library’. It was also spent on library necessaries like ‘paper, pens and ink, and postage’, ‘for binding books’ or still ‘for transcribing a copy of the New Catalogue for the library’. All these wonderful details, sometimes scribbled in tiny script, allow us to get a better understanding of the early history of the library and its management.