We have recently completed the online cataloguing of the MacKinnon Collection, of books of and about Scottish life and literature, and rich in books in Gaelic. Our colleague and expert in Gaelic, Donald William Stewart, has contributed this guest blog about Donald MacKinnon and his books:

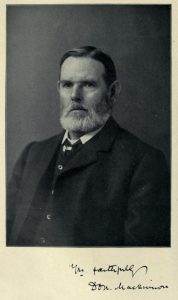

The Greatest Gaelic Book Collector? Professor Donald MacKinnon (1839–1914)

Donald MacKinnon was born in 1839 in Kilchattan on the Argyllshire island of Colonsay. He was the first Professor of Celtic Languages, Literature, History, and Antiquities at the University of Edinburgh, and he made substantial contributions to every one of the fields listed in his title. MacKinnon occupied the chair from 1882 until he retired in summer 1914. He died a few months afterwards, on Christmas morning, at his home at Balnahard in his native island.

As a student at Edinburgh, MacKinnon enjoyed a dazzling career crowned in 1869 by the Hamilton Fellowship in Mental Philosophy, a grant of £100 allowing him three years’ further study at the university. Ironically, it was the Education Act (Scotland) of 1872, that ruthless destroyer of Gaelic schools, which was to give him his big break. After the Act was passed, Donald MacKinnon was appointed as the first Clerk and Treasurer of the School Board of Edinburgh.

Admirers of Donald MacKinnon – and, it has to be said, on occasion Donald MacKinnon himself – have made much of his humble beginnings, but we should remember that talent often attracts sponsors. MacKinnon was fortunate to have caught the attention of two of the most influential figures in Scotland, men who just happened to be from Colonsay like himself. Advocate and judge Duncan McNeill, first Baron Colonsay (1793–1874), was the pre-eminent Scots lawyer of his time; while his younger brother Sir John McNeill (1795–1883), chairman of the Board of Supervision in charge of the operation of the Poor Law (Scotland) Act, was the most powerful civil servant in the country. Long before the Edinburgh Chair of Celtic was finally established in 1882, MacKinnon’s patrons were unobtrusively promoting the merits of their candidate.

MacKinnon was certainly an ideal contender for the professorship: an excellent Gaelic prose stylist, an industrious contributor of columns to newspapers and periodicals, a man who participated to the full in the lively Gaelic-speaking community in the capital – and who would soon undertake arduous service on the parliamentary Napier Commission travelling around the Highlands enquiring into crofters’ and cottars’ rights. MacKinnon was also a popular teacher of a generation of Gaelic students, including the first women Celtic scholars in Scotland. In particular, as the pioneer Celtic Professor in Scotland, Donald MacKinnon had to lead the way and lay the foundations for future scholarly study of Scottish Gaelic. This he did with aplomb. His lectures defined and delineated Gaelic literature and history, as well as elucidating Gaelic place-names and personal names. His Gaelic Reading Books laid down a syllabus for elementary and advanced students in the language. Most enduringly, his Descriptive Catalogue of Gaelic Manuscripts in the Advocates’ Library, Edinburgh, and Elsewhere in Scotland(Edinburgh: T. & A. Constable, 1912), the fruits of five years of research generously sponsored by John Crichton-Stuart, fourth Marquess of Bute (1881–1947), remains a crucial work of reference for both classical and vernacular Gaelic manuscripts in Scotland – including four then in MacKinnon’s own possession – more than a century after its publication. But, as the new online library catalogue to Professor Donald MacKinnon’s collection demonstrates, he should also be remembered as a great collector of books, Gaelic and Celtic.

At a complimentary dinner held in MacKinnon’s honour by friends at the Waterloo Hotel on 7 November 1883, marking the beginning of his professorship, the Rev. Dr Norman Macleod ‘presented to Professor Mackinnon a cheque for a sum subscribed by a few friends, who begged him to apply it in the purchase of books bearing on the subject of his Chair. (Applause.)’ [Edinburgh Evening News, 8 November 1883, 2]

The minister’s remark suggests that even before he became a professor, Donald MacKinnon was already well-known as a Gaelic book-collector. This is borne out by the Rev. Donald Maclean’s remarks in the introduction to his magnificent catalogue, financed by the Carnegie Trust, Typographia Scoto-Gaedelica or Books printed in the Gaelic of Scotland (Edinburgh: John Grant, 1915):

The late Professor Donald Mackinnon placed at my disposal very valuable bibliographic material which he had collected for many years before he became the first occupant of the Celtic Chair in Edinburgh. It is not possible for me to acknowledge fully my indebtedness to this collection. (viii)

In making MacKinnon the Typographia’s dedicatee, Maclean pays tribute to the professor’s assistance and encouragement – and to the breadth and scope of his Gaelic library.

MacKinnon’s collection had already been at the heart of a major Gaelic books presentation, one of the attractions, along with quaichs, silverware, tartans, and regimental uniforms and colours, shown in the Highlands and Islands display in the Fine Art Galleries at the great Scottish National Exhibition in Saughton Park between May and September 1908. During this time of the Scottish Celtic Revival, Gaelic culture, sports, and costumes loomed large in the Exhibition programme, alongside the helter-skelter tower, the switchback railway, the water chute, the Irish cottages, the Senegal village, the display of baby incubators, and diverse other attractions intended to educate, entertain, and astonish.

Among the books Professor MacKinnon donated to the exhibition, as listed by The Scotsman on 22 August 1908, were:

• the Irish translation, by Uilliam Ó Domhnuill, of the New Testament, first printed in 1681;

• the first edition of the New Testament in Scottish Gaelic, 1767;

• the first edition of the Old Testament in Scottish Gaelic, printed in four parts, in 1783, 1786, 1787, and 1801;

• a very rare copy of the Apocrypha translated into Scottish Gaelic for Prince Lucien Bonaparte by the Rev. Alexander MacGregor in 1860.

It should be pointed out here that MacKinnon was one of the scholars who revised the Gaelic Bible for the SPCK in 1902. The professor probably also contributed:

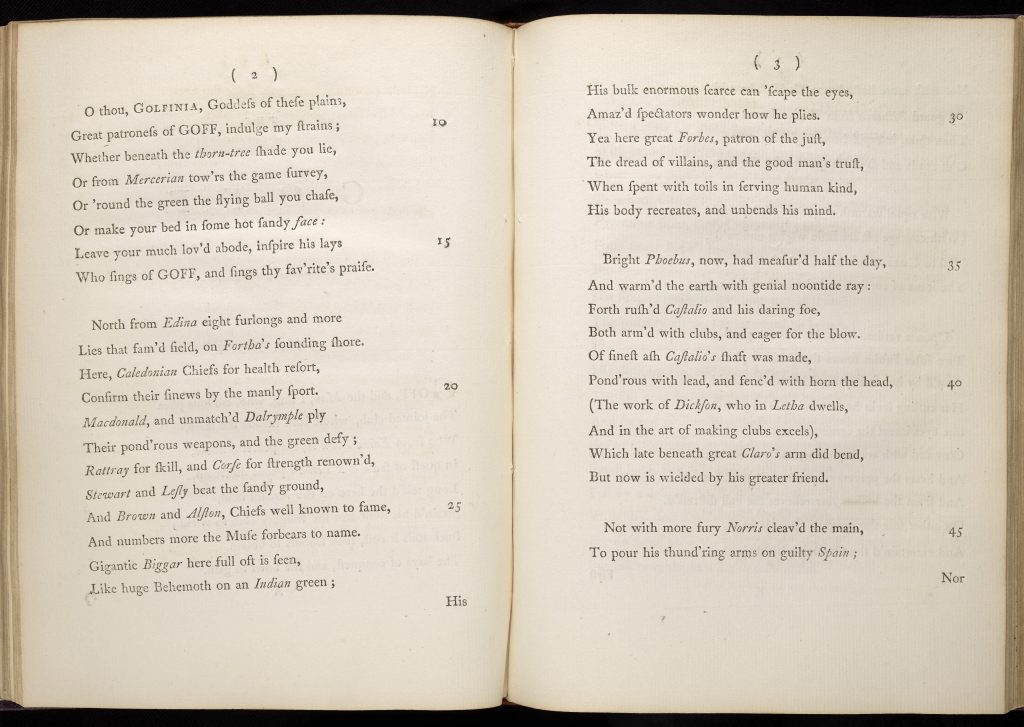

• James Macpherson’s Fragments of 1760;

• Ais-eiridh nan Seann Chánoin Albannaich, the Resurrection of the Ancient Scottish Language by Alexander MacDonald, Alasdair mac Mhaighstir Alasdair, the first purely literary publication in Scottish Gaelic, printed in 1751;

• Comh-chruinneachidh orranaigh Gaidhealach, the Eigg Collection, songs edited by Alexander’s son Ronald and printed in 1776;

• An Sùgradh, a small popular song collection from 1777;

• Gillies’ collection Sean Dain, agus Orain Ghaidhealach of 1786;

• the blind poet Allan MacDougall’s song collection Orain Ghaidhealach of 1798.

Now, not all of the major works listed above are found in the MacKinnon Collection today. This raises the possibility that the professor’s books arrived at Edinburgh University Library in two tranches. Whether during his later years as professor, or after his retiral, Donald MacKinnon may have donated to the Celtic Departmental Library at Edinburgh the canonical works of Gaelic literature on which his courses were principally based, works such as those mentioned above. His personal library, on the other hand, was bequeathed to his friend and fellow islander Dr Roger McNeill (1853–1924), Medical Officer for Argyllshire, a man whose remarkable research and tireless campaigning was instrumental in founding the Highlands and Islands Medical Service in 1913, one of the main forerunners of our National Health Service today. After McNeill’s death, MacKinnon’s volumes, probably augmented by those from the doctor’s own collection, were bequeathed to Edinburgh University Library. It would be an interesting and useful exercise to see how far we can relate the books in the MacKinnon Collection, and others in the university collections probably once owned by Donald MacKinnon, with the listings in Maclean’s Typographia.

In Professor Donald MacKinnon we have a scholar signal for the range of his interests and expertise even in an era noted for polymaths, a man celebrated by his colleagues and students, and remembered today for a number of crucial works of scholarship and reference. The MacKinnon Collection is one of the professor’s greatest legacies, allowing us to gain a clearer picture of one of Scottish Gaeldom’s most eminent scholars, and also, through him, a deeper understanding of Gaelic culture itself.

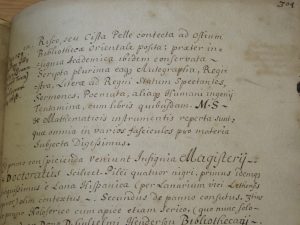

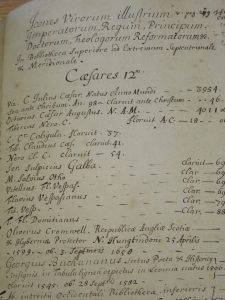

The library has, from very early on, been a welcoming home to objects other than books. This can be seen in items Da.1.18 and 19, as both contain several lists of wonders and curiosities. We are indeed told that precious items were kept in a chest – a sort of 17th century equivalent to our fire-safe! Among the items precious enough to go in the chest were the Bohemian Protest, the marriage contract between Mary Queen of Scots and Francis Dauphin of France, and a thistle banner printed on satin 1640 being found carelessly put in one of Mr Nairn’s books. What is more, a list is given us of portraits that were hung in the library, a celebration of illustrious men and women. Featured celebrities included Tiberius Claudius, Martin Luther, and Mary Queen of Scots. We still do hold some of these portraits. Items related to the discipline of anatomy were also gifted to the library, and we are told in several lists that these comprised the ‘skeleton of a French man’, or a ‘gravel stone (…) cut out of the bladder of Colonel Ruthven’, who, we are informed in Da.1.31, ‘lived six weeks thereafter’.

The library has, from very early on, been a welcoming home to objects other than books. This can be seen in items Da.1.18 and 19, as both contain several lists of wonders and curiosities. We are indeed told that precious items were kept in a chest – a sort of 17th century equivalent to our fire-safe! Among the items precious enough to go in the chest were the Bohemian Protest, the marriage contract between Mary Queen of Scots and Francis Dauphin of France, and a thistle banner printed on satin 1640 being found carelessly put in one of Mr Nairn’s books. What is more, a list is given us of portraits that were hung in the library, a celebration of illustrious men and women. Featured celebrities included Tiberius Claudius, Martin Luther, and Mary Queen of Scots. We still do hold some of these portraits. Items related to the discipline of anatomy were also gifted to the library, and we are told in several lists that these comprised the ‘skeleton of a French man’, or a ‘gravel stone (…) cut out of the bladder of Colonel Ruthven’, who, we are informed in Da.1.31, ‘lived six weeks thereafter’.

The belt is made from a strip of ribbon, embroidered with enamelled motifs in the signature white, green and purple associated with the suffrage movement. It has a pink lining on the reverse and a gilt buckle fastening. The belt is in amazing condition despite some oxidisation of the silver in the ribbon, leading the silver threads to turn dark grey.

The belt is made from a strip of ribbon, embroidered with enamelled motifs in the signature white, green and purple associated with the suffrage movement. It has a pink lining on the reverse and a gilt buckle fastening. The belt is in amazing condition despite some oxidisation of the silver in the ribbon, leading the silver threads to turn dark grey.