We are delighted to be sharing a guest blog post by Elizabeth Cary Ford and Vivien Estelle Williams of Glasgow University who have recently been studying the marginalia of item De.8.83 in the CRC collections.

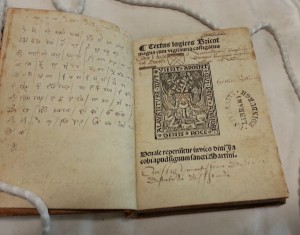

James Douglas’ copy of Thomas Bricot’s Textus Logices and its musical marginalia

Kenneth Elliott, the late eminent scholar, identified a basse danse written in the margins of a sixteenth-century book. The existence of the score of the basse danse was quite a well-known fact in academia; but the original source for it was not. We are pleased to say that we have been able to track the book in which the marginalia appears to the University of Edinburgh Special Collections, item De.8.83. The field of the basse danse in Scotland is certainly understudied, and we hope this finding will add a piece, however small, to the wider picture.

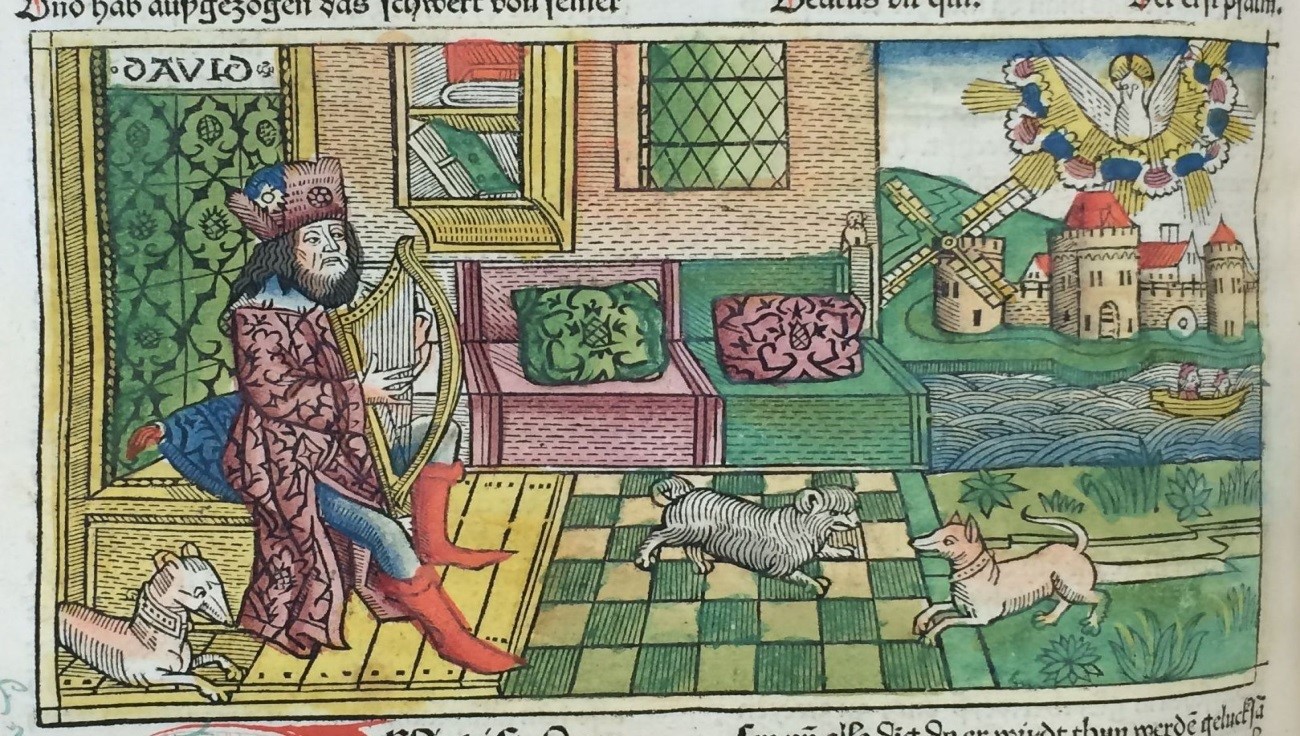

Basse danses were very popular in Europe in the fifteenth and sixteenth century. This type of dance probably originated in Burgundy. It quickly travelled to other European courts and was certainly known in Scotland after King James V’s second marriage in 1538 to Marie de Guise, if not before. It is reasonable to assume that this basse danse was part of the repertoire of the French musicians who travelled with the queen.

Kenneth Elliott transcribed the tune from the source and shared it with John Purser, who published a portion of it in Scotland’s Music. Elliott described the tune as “[a]n anonymous instrumental composition possibly of Scottish authorship and related to the basse-danse is recorded in an early-sixteenth-century source”. According to Purser’s note, the book was passed from Hector Boece to Theophilus Stewart and to James Douglas. This is confirmed by an inspection of the book, as well as the University of Edinburgh’s records of the book.

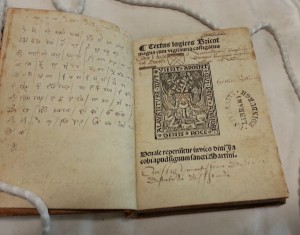

All we knew about this dance was that it was marginalia, and that Kenneth Elliott was the first person to call attention to it. Thanks to Dr Theo Van Heijnsbergen and Dr Nicola Royan we discovered that the volume in question was a little publication by Thomas Bricot: Textus Logices, c. 1513.

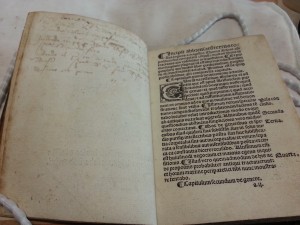

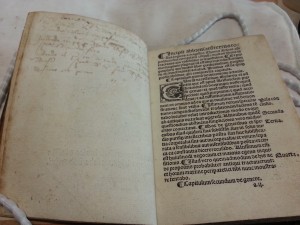

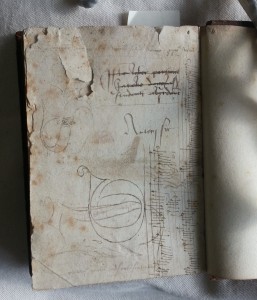

The author of the book, Bricot, from the diocese of Amiens, studied in Paris during the late 1470s, where he went on to teach philosophy. His major publications were dedicated to the discipline of logics, as is our Textus Logices. The small volume, re-bound in the nineteenth century, was possibly intended as a teaching aid or a textbook; 136 beautifully-printed leaves on the subjects of logics, as well as Aristotelian and Porphyrian works. The various handwritings of the marginalia, and in the flyleaves and end-papers show that the book has passed through various hands.

Amongst the calligraphies and signatures a few are more clearly discernible: on the title-page there is a “Codex Hector Boethi” and a “Hethor Bethius”. Hector Boece, c.1465–1536, was born into a prominent Dundonian family. He was a historian and the first principal of the University of Aberdeen. He most probably came in contact with Bricot’s publication in Paris as a student at the Collège de Montaigu. The annotations in the volume are extensive, which may well indicate the mark of an informed reader. We doubt whether Boece would have written the score himself, as given his known persona a casual treatment of a book would be unlikely.

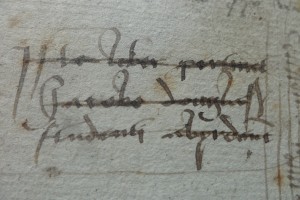

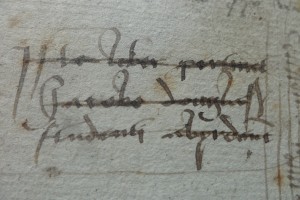

On the fly-leaves are other ownership marks; this may indicate they were added after binding. Theophilus Steuart is mentioned in the Fasti Aberdoniensis as a “gramaticus”, as well as the Analecta Scotica, as “Maister theophelus stuart, master of the gremer skuill of ald Aberdeen”. This Aberdeen connection links Steuart with Boece, as both were based at King’s College.

It could be that James Douglas, potential source of the tune, was the Earl of Morton (c. 1516 – 1581) as he had dealings with the University of Aberdeen. David Stevenson points out that “The general assembly in 1574 requested that the then regent, the 4th Earl of Morton, to take orders that doctors may be placed in the Universities and stipends granted unto them”.

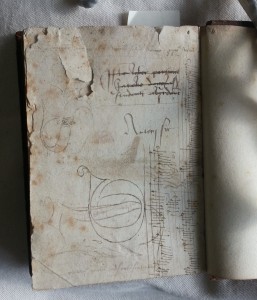

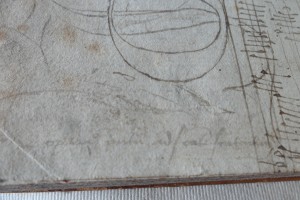

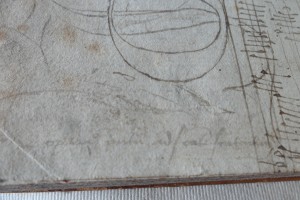

The book contains two sections of musical notation. The first is a snippet of what could be a basse danse. The dance in full is scribbled in the back of the book, between annotations. The handwriting of the score would appear to date from the sixteenth century. Does this mean the dance was current and popular at the time? Did James Douglas himself compose it? As there is no searchable index of tunes for basse danse, unfortunately we have not been able to verify whether or not the tune was known and popular. What comes as no surprise is that French music was popular in Scotland in the sixteenth century, owing to the cultural ties of the Auld Alliance.

This marginalia is early evidence for the basse danse in a Scottish source, no matter who the author may have been. We will never know why this dance was scribbled in the fly-leaves of a philosophical treatise. It would be nice to think that, perhaps, the tune was popular amongst the students of the University of Aberdeen as a dance or a song – maybe we could picture a young James Douglas jotting it down, as his mind wanders, while at his desk during a lecture on logics!

For our finding and assistance with it we wish to thank: Denise Anderson, Francesca Baseby, Warwick Edwards, Luca Guariento, David McGuinness, Nicola Royan, Evelyn Stell, Theo Van Heijnsbergen, Janet Williams, Allan Wright.

This piece is dedicated to John Purser, our druid in the West.

Elizabeth Cary Ford Research Profile

Vivien Estelle Williams Research Profile