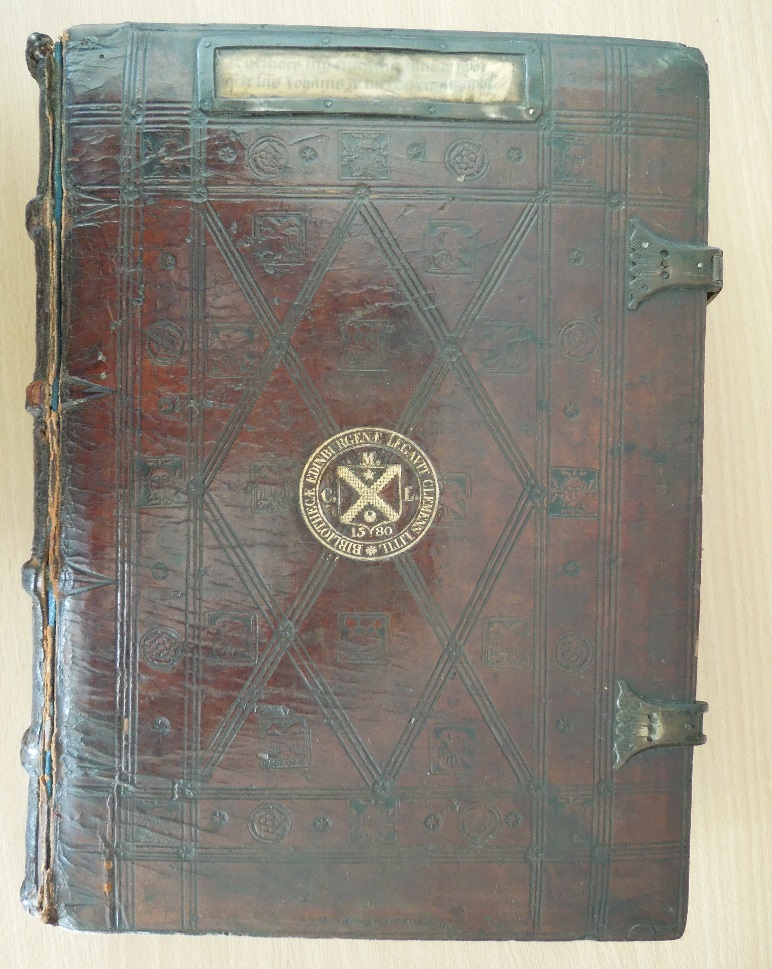

Sometimes in rare book cataloguing you come across something that requires you to flex you analytical bibliography muscles. It can be amazing what you can gather from the study of the physical form of a particular volume.

In the following case we managed to learn quite a bit about the printing practices in Cologne during the 1470s from the study of one page.

So, one day I was merrily cataloguing CRC Inc.S.16/2 (De excidio Troiae historia. Not printed after 1472) when I turned a page and found this:

Not actually a bad photograph, but a badly printed page. Possibly what is known as a “slur” where the platen (we’ll get into that later) moves during the printing process and causes the ink to smear. But more likely the platen was lowered twice on the same page, whether on a one- or two-pull press is open to debate.

So far, so what. ¯\_(シ)_/¯

Well, it occurred to me that there was only one mis-printed page. In the printing process there will always be a partner page printed on the same sheet, which is then folded. So, I checked the partner of our mis-printed page and found that it wasn’t blurred. This book was a quarto which meant, as I’m sure you’re all thinking, that that was impossible.

Okay, so a lot of jargon there. Let me break this down.

This is a diagram of a hand-pulled press. Showing the frisket, tympan, forme, press stone and the aforementioned platen.

(Public domain image made available by Smithsonian Libraries (AE25.E53X 1851 Plates, t.7, “Imprimerie en caracteres,” plate 15))

- Frisket: Used to hold the paper in place on the tympan and to mask off areas that you don’t want printed.

- Tympan: Holds the paper using small pin-like pieces of metal.

- Forme: The name given to the frame that the type is tightly packed into.

- Press Stone: The frisket and tympan are folded onto the press stone.

- Platen: Is the part of the press that applies the pressure to the paper on the forme.

The illustration above is actually a two-pull press. In this case the press is set up for a quarto sheet with four pages to be printed. The stone is rolled under the platen once, the platen is pressed down printing two pages, then it’s lifted and the stone is rolled further in and the platen is lowered again, printing the final two pages.

In the case of a one pull press, the platen is lowered once. If it’s a folio then one page is printed, if it is a quarto then two pages are printed. After it’s printed, the forme is reset with the next page(s) to be printed.

Now the complicated bit.

Let’s talk about formats. Folio, quarto, octavo, etc.

The format of a book is determined by how many pages are printed on a sheet and how many times that sheet is folded.

So, for example, one sheet of paper is printed on both sides, then folded once.

This is a folio. It’s folded once along the y-axis. Giving two leaves or four pages.

Front of sheet

Back of sheet

The Folger Library has an interesting website that lets you play with Shakespeare’s First Folio where you can assemble sheets into “gatherings”.

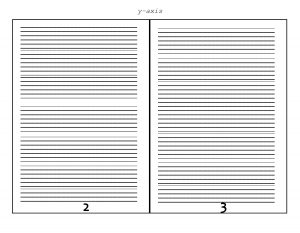

This is a quarto. It’s folded twice. First the y-axis, then the x-axis giving four leaves or eight pages.

Front of sheet

Back of sheet

Check out this video to see how it’s done.

Octavos are folded three times, giving you eight leaves or sixteen pages. And so on …

Okay now that we’re all experts on formats, let’s stampede over to chain lines.

Chain lines are formed during the paper making process. The mould used to make the paper is dipped into a vat of pulped linen and the water is sieved away leaving behind an impression of the mould.

Check here to see the process.

The mould consists of wire sewn onto supports, it’s these supports that leave the chain line impressions.

Here’s a paper mould.

The thicker, vertical lines you can see are imparted onto the sheet of paper during the paper-making process and will end up looking something like this.

Chain lines help to determine the format of a volume. With a folio the sheet is folded once along the y-axis, therefore the chain lines will be vertical on the page. If there is a watermark (and there isn’t always!) it is placed on the right-hand side of the sheet.

In the example below there’s a watermark on the right-hand sheet and a countermark on the left. When the sheet is folded the chain lines will be vertical and the watermark will be in the centre of the page.

Folio

With a quarto the sheet is folded once along the y-axis, then once along the x-axis therefore the chain lines will be horizontal on the page. The watermark will be in the gutter, often difficult to see, especially in tightly bound books.

Quarto

Phew! Okay, we now have all that knowledge, so here’s why that blurry page is so weird. The chain lines and watermarks in the book show that it is a quarto. And if you remember from before, quartos are printed either two or four pages at a time, so how can there be only one mis-printed page on a sheet? The conjugate page should be mis-printed as well.

When the platen lowered the mis-printed page should have had a mis-printed partner:

If the red page is the mis-printed page, then the green page must be mis-printed because the platen would be lowered on the both at the same time.

No such mis-printed partner existed.

Headaches ensued.

More headaches.

Much sighing.

Light-bulb!

This volume was printed before 1476, we know this because the rubricator (someone who would emphasise areas of the text with red ink) very kindly dated his rubrication. So, it’s a very early quarto. What if the printer viewed printing a quarto like printing a small folio?

Possibly they used a half sheet and imposed the quarto as a folio, and then printed it a page at a time. That would allow for only one page to be mis-printed. We checked the watermarks and chain lines and established that these were indeed half sheets.

Calls went out on Twitter; colleagues were asked for their opinions. Robert MacLean at the University Glasgow put us on to Karina de la Garza-Gil at the University of Cologne who confirmed that the common practice for Cologne printers at that time was to print quartos in half sheets one page at a time.

All that was left was to work out how it happened.

There is no smearing of the ink, and the first printing is sharp if faint. This makes it unlikely that anything twisted or moved, so perhaps the printer lowered the platen once and changed their mind before lowering it with the required force a second time.

The final mystery: was it a one or two pull press? It would be pure speculation to decide either way. Arguments could be made for either. At this point you really need to be able to read the mind of a printer from five hundred years ago. What we do know is that printing quartos on full sheets on a two-pull press became common a few years after this particular book was printed.

In the end what this does show, is how much information can be gleaned from analysing the physical properties of a book. From one mis-printed page we established the printing practices in Cologne from five hundred years ago.

And that end’s the tale of the blurry page!