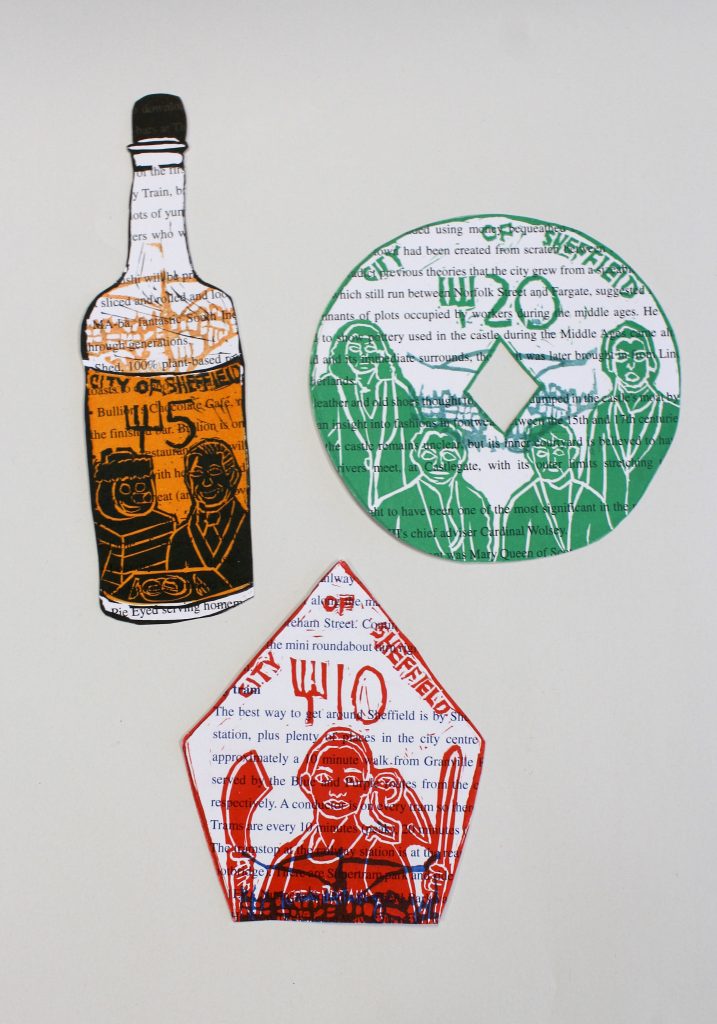

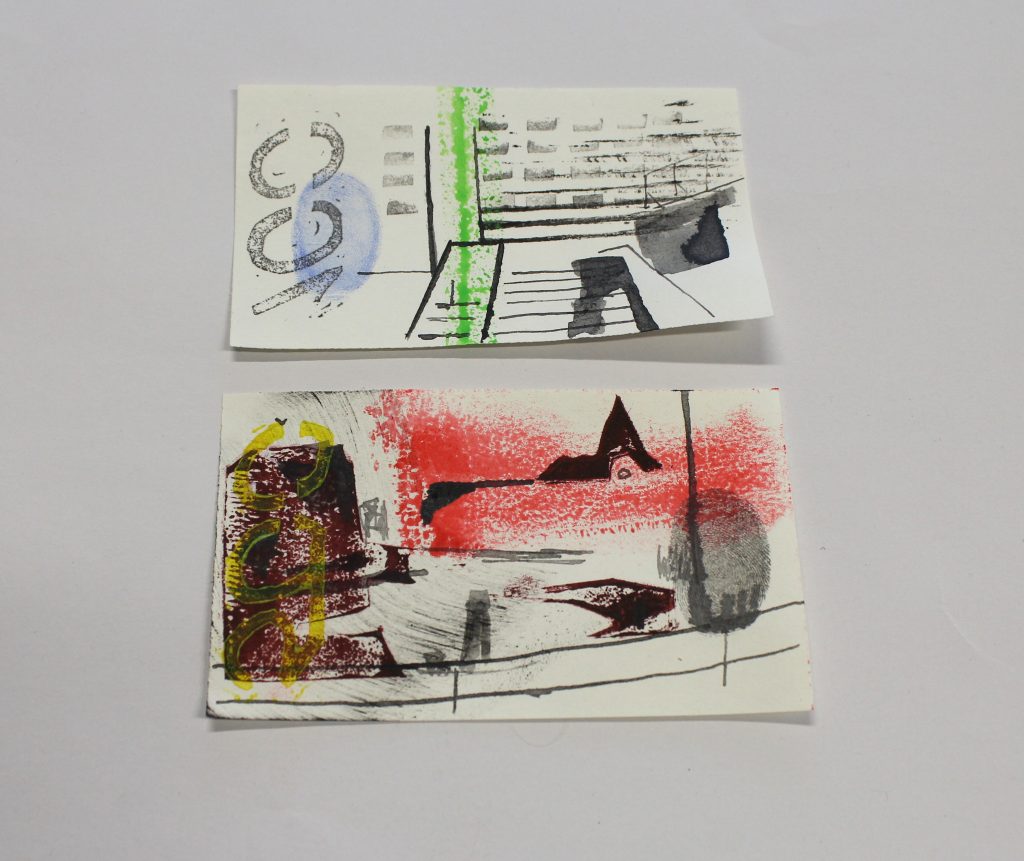

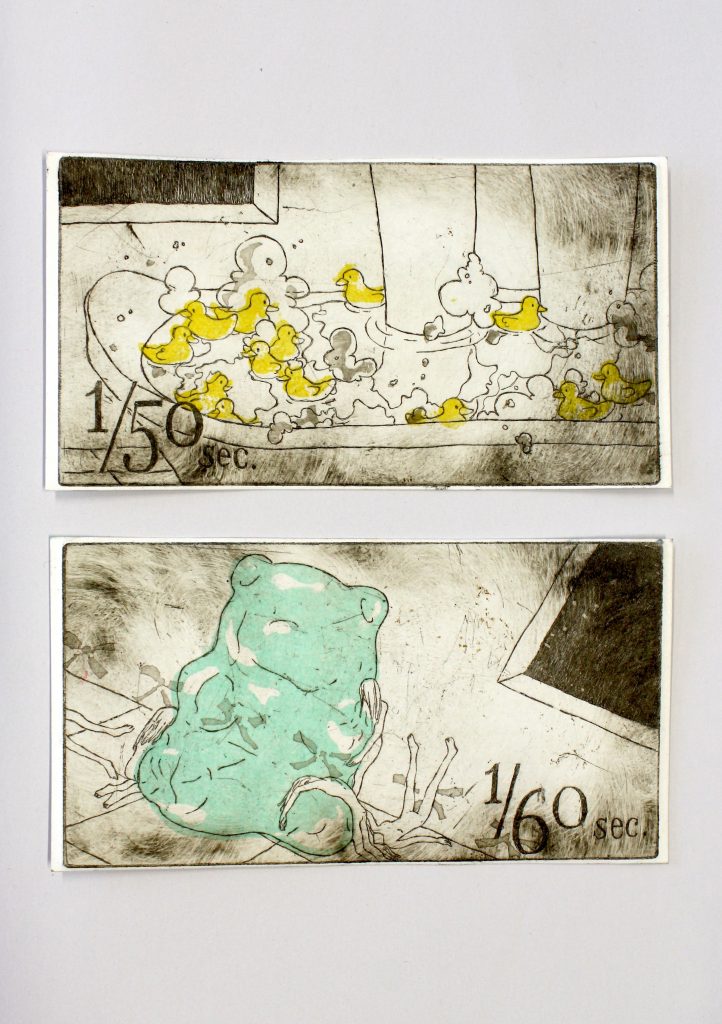

During the academic year 2019-20 Rare Books worked with a group of third year students from Edinburgh College of Art. The project was to produce an artist’s book in response to the collections and space of the Playfair Library room in Old College, the home of the University Library from 1827 until it moved to George Square in 1967. The project ended with a photoshoot in the Playfair a few days before the country was put into lockdown in March 2020. The project website, which shows all the student work, was delayed by the pandemic, and went live early in 2021.

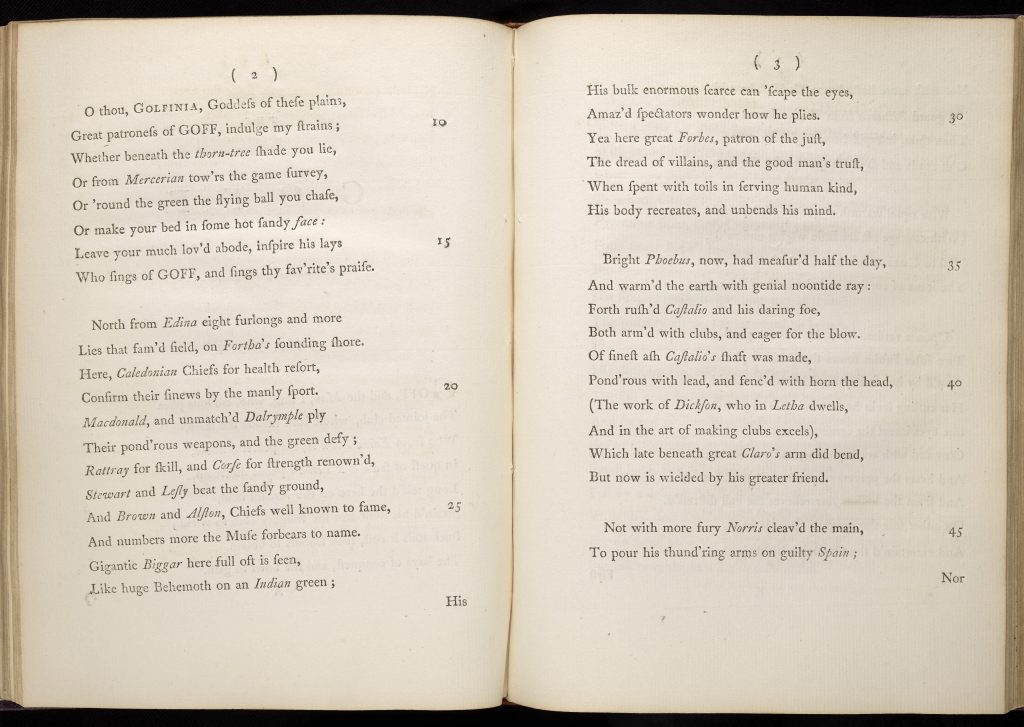

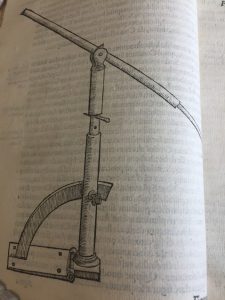

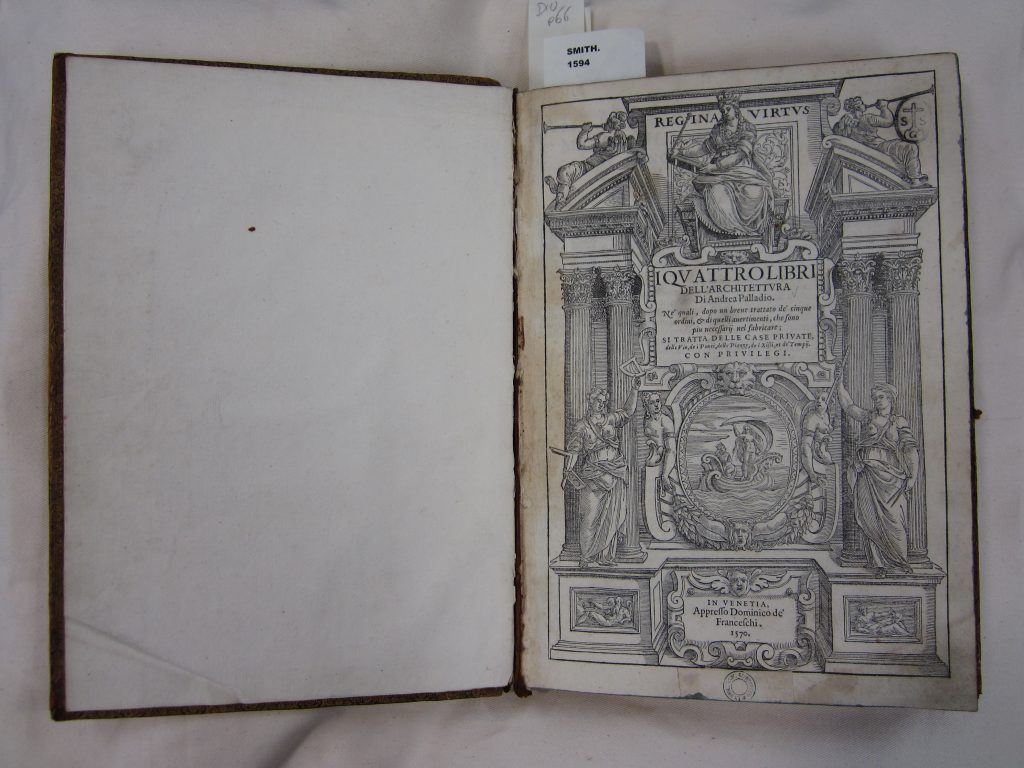

The challenge the students were set was to make reference to at least one book which had at some time in its history been on the shelves in the Playfair Library. To achieve this they had to get to grips with the records of the collection when it was there.

This really was a challenge. Read on find out why…

How to Arrange an Old Library

Like many libraries from the Middle Ages until the nineteenth century, the Playfair is a long, narrow rectangle, with windows on both sides, and bookcases projecting into the room at right angles. It is a particularly grand and elaborate example, having an upper, gallery level, which continues the pattern right up to the ceiling.

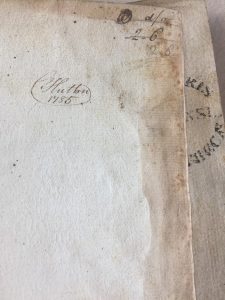

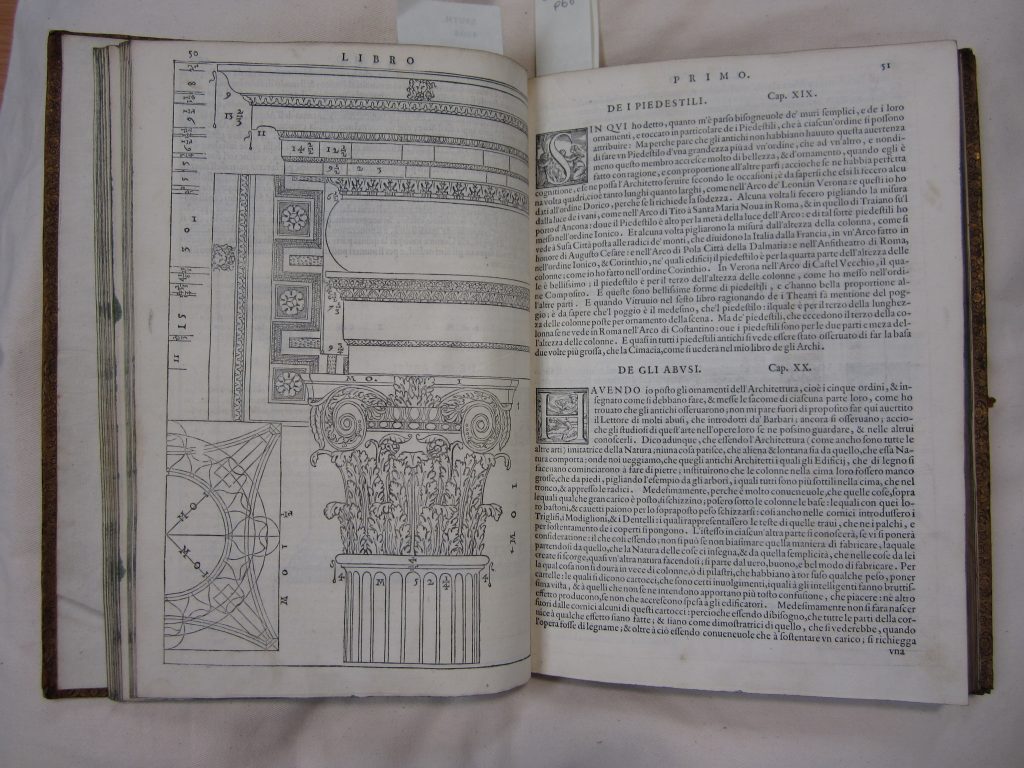

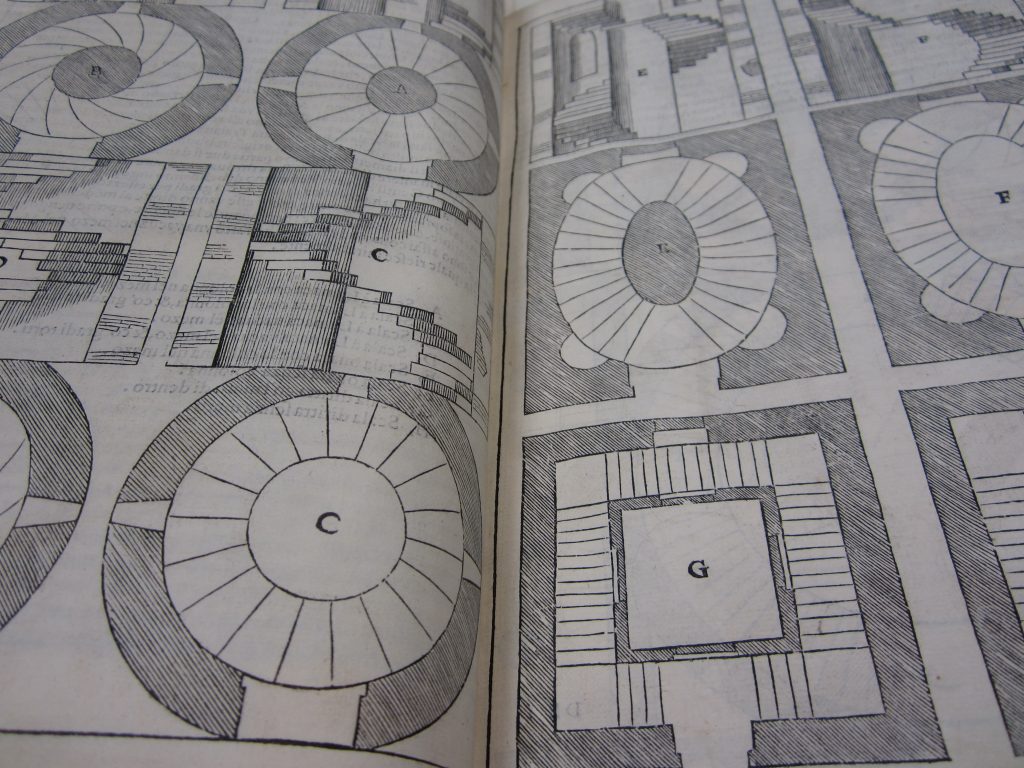

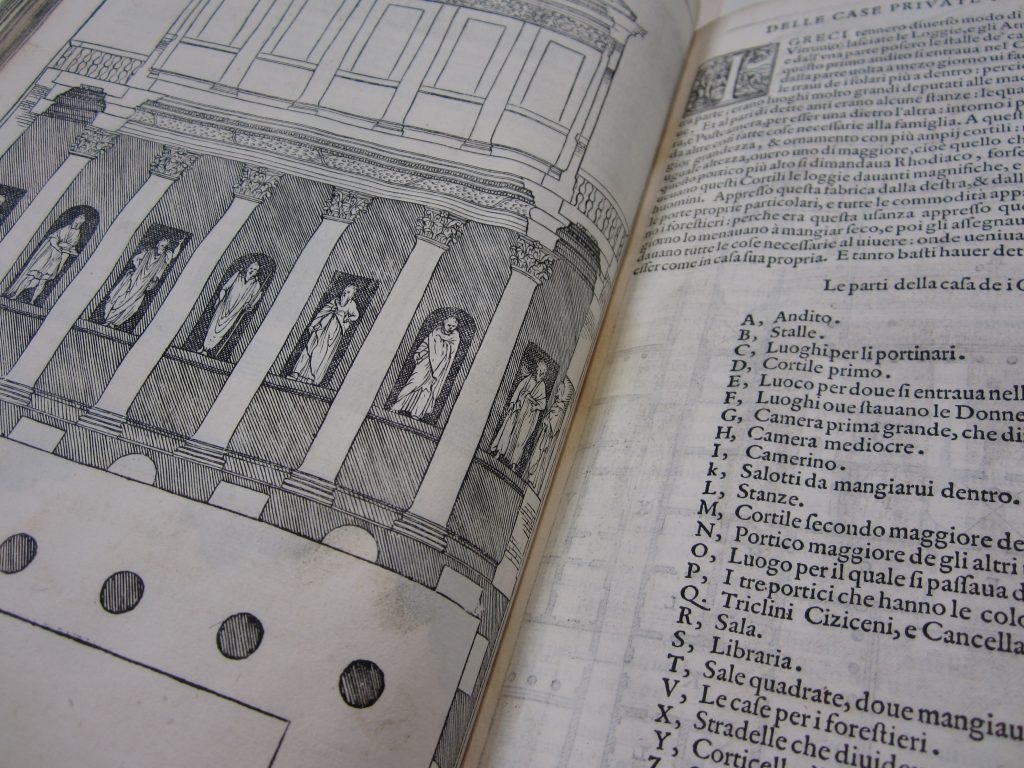

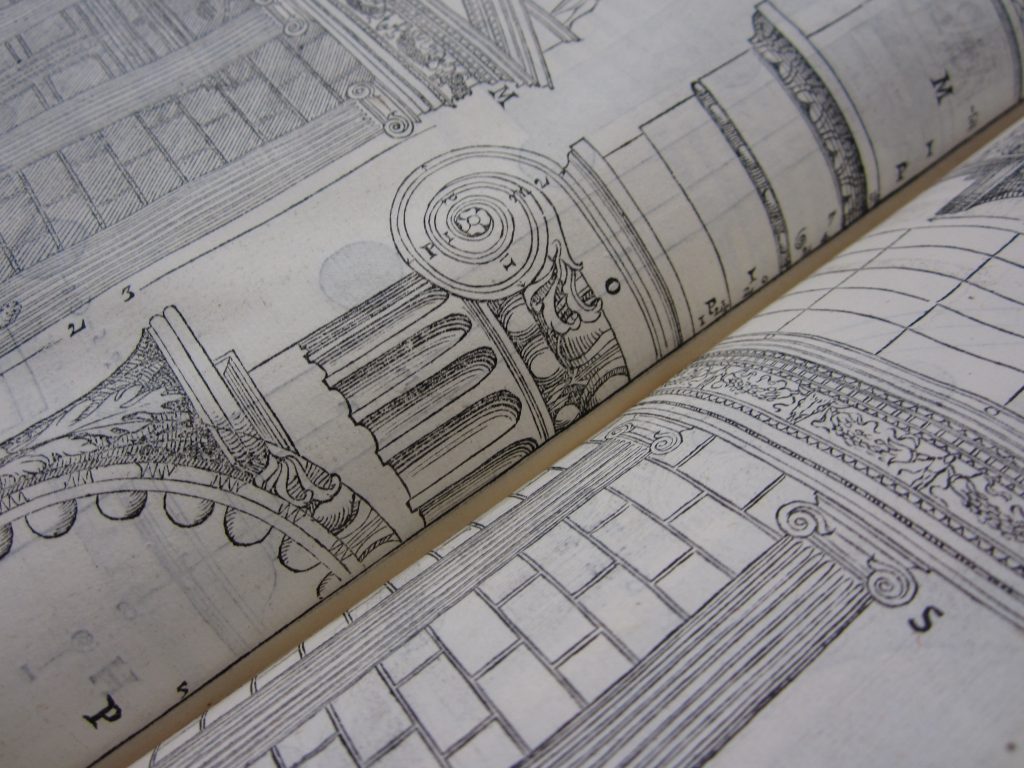

The books were arranged by what is called ‘fixed shelf location’, meaning that each book had a designated place on a particular shelf. Each bay was labelled with a letter of the alphabet; each shelf was numbered; and the books on each shelf were numbered. This set of three characters was written in the books and in the catalogue, as the means of finding them. Modern libraries tend to use a subject classification scheme, which arranges the books in relation to one another in a linear sequence, whereas in the Playfair the arrangement of the books was defined by the architecture of the library. It was three-dimensional rather than linear; there were relationships between books on shelves above, below and opposite, as well as next to one another. Larger books were likely to be on a bottom shelf and smaller ones in the upstairs gallery.

The books were grouped by subject into the different bays of the library. For example:

A: Bibles and the Church Fathers (Religious books were put first)

G – K – Medicine

L – Natural history

O – Maths and physics

P – Geography and topography

S – Poetry and literature, including songs with music

T – Language; grammars etc.

Although all the books left the Playfair Room in 1967, many of them are still arranged according to the Playfair shelfmarks. Divorced from their original location, these have been run together to form a series of sequences in the Centre for Research Collections’ stores. It is possible to imagine these back onto the now empty shelves in the Playfair, and get a spooky sense of what it must have been like when it was in use.

However, quite a lot books which were at some time in the Playfair have since been given new shelfmarks. Some newer books went into the open-access classified sequences in the library in George Square; others have been moved into different sequences within Special Collections. Books were moved around even when the library was in Old College, and not every book the library owned in the nineteenth century has survived to the present.

How to find Anything

So, for our students to be able to find books which were in scope for their project, they had to be able to tell the difference between Playfair shelfmarks and those from elsewhere in the library, use both the catalogues which record where the books are today and those which record the collection when it was in the Playfair, to detect books which have moved. If they wanted to base their work on an entire shelf, or other grouping, which was something we suggested they might do, they also needed the records of how the books were arranged.

The easiest place for them to look for ideas was the main University library search tool, the familiar discovered.ed.ac.uk – which will find records matching any words typed into it, and can limit its search to anything currently in Special Collections (choose “Special Collections – Main Library” and “Special Collections – Centre for Research Collections” for books which used to be in the Playfair)

So far, so familiar. But a lot of the old Playfair books are not catalogued on DiscoverEd at all, and it doesn’t help much for anything which has changed shelfmark.

The next easiest place to look is in the library’s last paper catalogue, the Guardbook which was closed when computers were introduced, in 1985. This is still used to find anything which isn’t online, and has been digitised. It was originally on typed sheets of paper in looseleaf binders. Typed only on one side of the sheet, additions were made on narrower sheets, bound to face the page they were adding to. The whole catalogue is arranged by author, while anonymous works, such as the Bible, go by title.

The experience of using it is very different from searching on a computer. You need to know what you are looking for and you need to be able to look it up in alphabetical order (The trick was to use reference books and bibliographies before trying the catalogue). On the other hand, once you get to the author it is easier than on the computer to browse, to assess at a glance what the library has, to discover the title wasn’t spelt the way you were expecting, or to spot what you wanted in a different version, or as part of a set.

Even the Guardbook records the collection as it was twenty years after it left the Playfair. To reach back to the Playfair’s heyday there are older catalogues. The easiest to use is the one published by the university in three volumes between 1918 and 1923

This is more manageable to use than the Guardbook, even in its online version, and from the point of view of Art and the Playfair, shows the Playfair room in full use, and contains much less material which was out of scope for the project. There are quite a few spare copies of this around, so one was sent back to the studios at ECA, for the students on the project to use.

There was one final, really scary, set of documents for the students to get to grips with…

How Not to Lose Anything in an Old Library

Catalogues, which allow you to find individual books in the library, are only one of the librarian’s tools for managing the collections. The other vital tool is a shelf list; an inventory arranged in the order the books are shelved. This makes it possible to check that nothing is missing, records exactly what is in each volume, if several things are bound together, and helped to keep track of where there was space on the shelves and where new books could most logically be added.

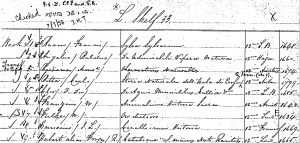

The last set of shelf lists for the Playfair was handwritten in the early twentieth century. These are still in use, though we now work on a digitised copy. They look like this:

For Art and the Playfair these allowed the students to explore some of the spatial relationships between the books stored in the room, although the handwriting, the crossings-out, and unfamiliar format presented a challenge.

And Then to Make Art

When we set up Art and the Playfair we had no idea how the students would handle this complicated and unfamiliar collection of documents, which as librarians we navigate on a daily basis and take for granted, but were very keen that they should engage with the records and the idea of the library as a space.

As it turned out, they rose to the challenge magnificently. Their biggest initial hurdle was getting over the surprise that they were not only allowed, but being encouraged, to work with very old books. But once they got started they all managed to find something which spoke to their own interests, and then produce something original and true to their own creativity. We were delighted that few of the books they chose were familiar to us, that some of them really got to grips with the difficult shelf lists, and that so many of them picked up unexpected features of their source material and took it to totally new places.

We wish all of the group well as they approach the end of their degree course this year, and make plans for the future.