Home University of Edinburgh Library Essentials

December 15, 2025

Cataloguing Christ’s Second Coming

The life of Edward Irving, minister of the National Scotch Church, London …/ Oliphant, Margaret, 1865. New College Library Special Collections SHAW 3

We’re delighted that the cataloguing of nearly 500 items held in the Shaw Collection on the Catholic Apostolic Church at New College Library, is now complete.

While further research is required to verify the history of this collection, it may have been put together by P.E. Shaw, author of The Catholic Apostolic Church, sometimes called Irvingite (A Historical Study); New York, 1946.

The Catholic Apostolic Church movement was inspired by Edward Irving, who began his career as a Church of Scotland minister who worked with Thomas Chalmers on his urban ministry projects. Irving moved to London where he became a strikingly popular preacher, predicting that the world was irredeemably evil and that the return of Christ and the end of the world was at hand. His charismatic services included controversial spiritual phenomena such as speaking in tongues.

The collection covers the liturgy, doctrines and government of the Catholic Apostolic Church movement, along with sermons and addresses by prominent figures in the church. This includes items written by eight of the ‘twelve apostles’ who were appointed after Irving’s death in 1835 – Henry Drummond, John Bate Cardale, Nicholas Armstrong, Francis Valentine Woodhouse, Henry Dalton, Thomas Carlyle, Francis Sitwell and William Dow.

The Catholic Apostolic Church believed in the imminent second coming of Christ, and the necessity of the restoration of a ‘perfect’ church in preparation for this event. Missionary activity took the movement to mainland Europe, Canada, and the USA, and the Church claimed 6,000 members in 30 congregations in 1851. In the twentieth century the movement dwindled and eventually fell silent.

- The testimony of the Apostles to the ecclesiastical and temporal heads of Christianity : composed in the year 1836. Chicago, Ill. : New Apostolic Church of North America, 1932. New College Library Special Collections SHAW 27.

The cataloguing of this collection was made possible by the generous donation of Rev. Dr. Robert Funk.

Sources

Oxford Companion to British History

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Lambeth Palace Library Research Guide : The Catholic Apostolic Church Collection

Christine Love-Rodgers, Academic Support Librarian, Divinity, with thanks to Janice Gailani, Funk Projects Cataloguer.

Dinosaur Hackfest

Whilst at the Open Repositories conference Kim and I were invited by Peter Sefton, University of Western Sydney, to a hackfest* to be held at the Informatics Forum the following week. Hackfests are a great way to meet other developers and learn new technologies in a fun and stimulating environment. This day organised by ContentMine was no different. Our aim for the day was to extract dinosaur facts from open access publications. After an introduction by Peter Murray-Rust, University of Cambridge, we were provided with coffee and set to work.

We successfully managed to get the quickscrape code installed and working, which is often easier said than done, and then wrote some new scrapers. All of the code is open source and available on GitHub:

Quickscrape platform https://github.com/ContentMine/quickscrape

Journal Scrapers https://github.com/ContentMine/journal-scrapers

Thanks to Peter Murray-Rust for inspiration, Peter Sefton for inviting us, CottageLabs for organising, PLOS for lunch, and Kim Shepherd for spending a day of his annual leave coding.

Claire Knowles, Library Digital Development Manager, @cgknowles

* Any event centered around programming and the rapid development of code over many consecutive hours, sometimes days.

Conserving Laing III

In April this year, I was lucky enough to be offered a 10 week internship to begin conservation work on the David Laing Bequest of rare books. This internship was funded by the National Manuscripts Conservation Trust and was the first stage in a series of projects on this collection, intended to stabilise and protect the most vulnerable items. It provided me with a fantastic opportunity for some hands on professional experience.

Based in the main library in George Square, I worked in the conservation studio surveying, cleaning, measuring, and rehousing this prestigious collection comprising around 1000 rare books. The treasures in the collection are worthy of the name, including poems in the hand of Robert Burns, and letters from Kings and Queens, as well as numerous early Scottish documents, and other significant literary papers. In only ten weeks, I had to complete work on the whole collection. It worked out at around ten minutes per book, so I wasn’t able to take the time to read very much of it…

The stages of conservation I undertook during this internship were, firstly, surveying and identifying the most vulnerable items in the collection, which were then measured so that individual boxes could be made for them. Secondly, I thoroughly dry surface cleaned the outside of every book, and the inside pages of some of the most vulnerable or dirty. Thirdly, I completed some repairs of loose and torn pages, and finally rehoused any loose pages, and all the vulnerable books into folders and boxes.

Here are a couple of pictures to show the difference a good clean makes to a bookshelf, look at the difference to the book on the end:

Before

After

As well as cleaning a lot of books, I spent a little time during this internship visiting other departments. One of the huge benefits of an internship like this is the opportunity for professional development, with studio visits, lectures, and work swaps, which I took full advantage of. I even spent some time working with the preventative conservation team packing musical instruments, which made an interesting change from cleaning books… although I think I know which I prefer!

A piece from the extensive musical instrument collection- It was a lot heavier than a book!

A piece from the extensive musical instrument collection- It was a lot heavier than a book!

A huge thank you to Joe Marshall, Ruth Honeybone, Caroline Sharfenburg, Serena Fredrick, and Emma Davey for all the guidance and help they gave me throughout this project, and everyone in the CRC for being unwaveringly welcoming and supportive.

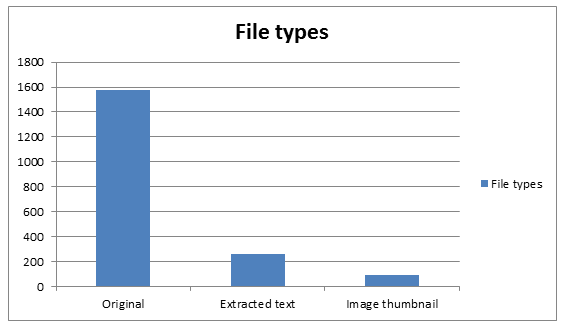

Open data repository – file size analysis

The University of Edinburgh’s open data sharing repository, DataShare, has been running since 2009. During this time, over 125 items of research data have been published online. This blog post provides a quick overview of the the number, extent, and distribution of file sizes and file types held in the repository.

First, some high level statistics (as at March 2014):

- Number of items: 125

- Total number of files: 1946

- Mean number of files per item: 16

- Total disk space used by files: 76GB (0.074TB)

DataShare uses the open source DSpace repository platform. As well as stroring the raw data files that are uploaded, it creates derivative files such as thumbnails of images, and plain text versions of text documents such as PDF or Word files, which are then used for full-text indexing. Of the files held within DataShare, about 80% are the original files, and 20% are derived files (including for example, licence attachments).

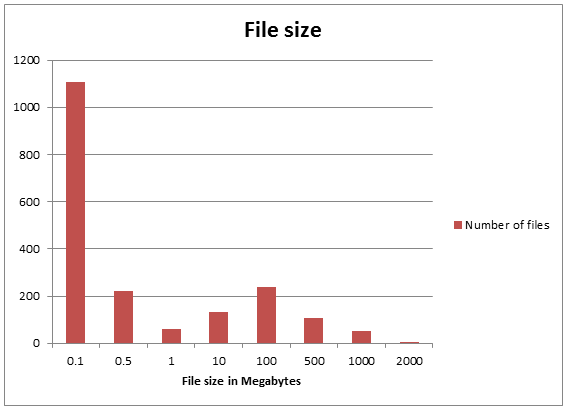

When considering capacity planning for repositories, it is useful to look at the likely file size of files that may be uploaded. Often with research data, the assumption is that the file size will be quite large. Sometimes this can be true, but the next graph shows the distribution of files by file size. The largest proportion of files are under 1/10th of a megabyte (100KB). Ignoring these small files, there is a normal distribution peaking at about 100MB. The largest files are nearer to 2GB, but there are very few of these.

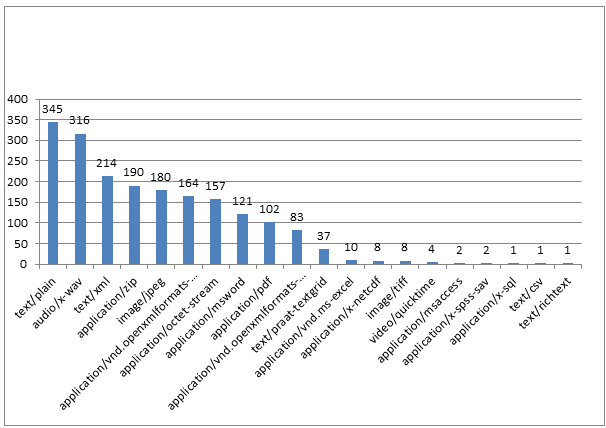

Finally, it is interesting to look at the file formats stored in the repository. Unsurprisingly the largest number of files are plain text, followed by a number of Wave Audio files (from the Dinka Songs collection). Other common file formats include XML files, ZIP files, and JPEG images.

Stuart Lewis

Head of Research and Learning Services, Library & University Collections

Data provided by the DataShare team.

New OUP ebook library collections for Social & Political Science

We’ve recently expanded our e-book collections with the Oxford Handbooks Online collection for Political Science (43 titles). This includes high demand titles such as the Oxford Handbook of Comparative Politics and the Oxford Handbook of Political Institutions.

We’ve recently expanded our e-book collections with the Oxford Handbooks Online collection for Political Science (43 titles). This includes high demand titles such as the Oxford Handbook of Comparative Politics and the Oxford Handbook of Political Institutions.

The successful negotiation of consortial purchasing agreements across Scottish Higher Education institutions has now given us access to all the collections in Oxford Scholarship Online. We already had access to the Political Science collection, but we now also have access to titles in Sociology and Social Work.

The successful negotiation of consortial purchasing agreements across Scottish Higher Education institutions has now given us access to all the collections in Oxford Scholarship Online. We already had access to the Political Science collection, but we now also have access to titles in Sociology and Social Work.

These collections allow unlimited user access and (within copyright) printing and saving of articles, making them good choices for inclusion on student reading lists.

Christine Love-Rodgers, Academic Support Librarian – SPS

Anon Art

Another visual essay from me this week. I thought it would be interesting to share a closer look at the amazing work of the invisible artists who populate the title pages of many books in our collections. I am constantly astonished at the graphic accomplishment present in these works from anonymous artists. I have spent some time highlighting details that are inspiring works in their own right. These works stand on their own feet and in their own space. All images this week are details from ” The Faerie Queene “. Shelfmark JY 1096. Points of note are the best snake tongue ever drawn (see below) and a fantastic phoenix rising from flames. More images from the book can be found within our image collections at http://images.is.ed.ac.uk/

Deputy Photographer, Malcolm Brown.

Open Repositories 2014

Last week I travelled to Helsinki, Finland, for the Open Repositories 2014 Conference, which had more than 450 attendees. The five days whizzed by with so much going on and my nervous anticipation of having to present on Wednesday morning. The week kicked-off with a DSpace meeting, we host multiple DSpace repositories for the Scottish Digital Library Consortium, as well as repositories for the University of Edinburgh, including the admin site for our new collections online service http://collections.ed.ac.uk. It was therefore very interesting to hear of the latest news from the DSpace mothership DuraSpace.

The week was full of lively debate from the Open Keynote on Tuesday by Erin McKiernan, https://twitter.com/emckiernan13, a physiologist and neuroscientist based in Mexico, who is committed to only publishing in open access journals. Through to the individual repository user groups on Thursday and Friday, with discussions carried on into the evenings social events. Adam Field, University of Southampton, produced a daily Wordle to highlight the most popular topics on the #or2014 Twitter hashtag, showing the diversity of interests.

The final Wordle of the whole conference:

On Wednesday, Kim Shepherd, from the University of Auckland Libraries and Learning Services, and I presented a paper on the use of existing repository technology for cultural heritage and special collections. This paper is available online at http://or2014.helsinki.fi/?page_id=985 (Parallel Session 4A) if you wish to see it, along with all the other main track papers.

The Congress Hall in the Paasitorni, the former Helsinki Workers’ House where the conference was held:

Kim and I also took part in the Developer Challenge in the ‘Fill My List’ team along with colleagues from the University of Southampton, where we wrote an application to populate drop-down boxes in forms with text and linked authority urls. The source code, list of team members and presentation is available at https://github.com/gobfrey/OR2014-chalege. We were chosen as one of the winning entries and hope to be able to develop this application into a service and integrate it with more systems.

The other members of the Fill My List Team:

Thank you to all the organisers and hosts of Open Repositories 2014 for an inspiring conference.

Claire Knowles, Library Digital Development Manager

@cgknowles

Manuscripts on display for Elizabeth Melville Day

From Monday 16th June to Friday 27th June manuscript work by Elizabeth Melville, Lady Culross is on display in New College Library. Two rare examples of early modern women’s writing are displayed together for the first time as part of the events around Elizabeth Melville Day on Saturday 21st June.

Elizabeth Melville, Lady Culross, was the first Scotswoman to see her work in print with the publication of her mini-epic ‘Ane Godlie Dreame’ in 1603.

She was the daughter of Sir James Melville of Halhill (1535/6–1617), the diplomat and autobiographer. Elizabeth was at the centre of a network supporting the exiled and imprisoned Presbyterian ministers, and her strong Calvinist faith is expressed in her writings.

On display is a volume of original letters, received by the University of Edinburgh in 1878 as part of the David Laing collection. It contains two holograph letters by Elizabeth to her son James (dated 1625 and 1629), nine to Reverend John Livingstone (eight holographs and one 19th century transcription, dated 1629-32), and one holograph to the Countess of Wigtoun (1630), and is a unique source of information about the poet.

This volume is displayed together with the Bruce Manuscripts, from New College Library Special Collections. The Bruce Manuscripts contains twenty nine sermons on Hebrews XI, preached in 1590-91 by Robert Bruce, Edinburgh minister. In 2002 Dr Jamie Reid-Baxter uncovered nearly 3500 lines of verse attributed to Elizabeth Melville contained in this manuscript.

Dr Joseph Marshall, Rare Books and Manuscripts Librarian & Christine Love-Rodgers, Academic Support Librarian – Divinity

Three different traits of open access publishers

This week I’ve been compiling some data for the next meeting of the RLUK Ethical and Effective Publishing Working Group. Some of the data itself is pretty interesting so I thought I would write a quick blog post and share some preliminary thoughts on what it means. The table below shows the top 5 publishers in terms of money spent on article processing charges (APCs) from the RCUK open access block grant in 2013-14.

| Publisher | Total spend | No. of APCs | Average APC | Discount on list price |

| Elsevier | £52,596 | 36 | £1,461.00 | 25% |

| Wiley | £51,781 | 35 | £1,479.46 | 25% |

| Public Library of Science (PLOS) | £23,737 | 24 | £989.04 | 0% |

| Nature Pub Group (NPG) | £21,226 | 8 | £2,653.25 | 0% |

| BioMed Central (BMC) | £20,746 | 16 | £1,296.63 | 15% |

Article processing charges (APC) for the most popular journals for Edinburgh authors.

We found that 2 publishers stood head and shoulders clear from the rest of the field. In terms of gross spend and number of articles published the top publisher was Elsevier, with £52.6k and 36 articles. In second place, with a similar publisher profile was Wiley with £51.8k and 35 articles. Both of these publishers were followed by PLOS, NPG and BMC who all had broadly similar spends of around £20k. Whilst the total cost per publisher is interesting, what is really noteworthy is the number of articles that money pays for, revealing something of the publisher’s strategy in the open access market place.

The lowest APCs are incurred from the open access journals – PLOS and BMC – who have fees roughly a third less than the other publishers. The highest APCs are incurred by hybrid journals, who also make money from subscriptions, and article reprints. NPG stand out from the crowd as they charge nearly double compared to their competitors.

In summary, what we see here are broadly 3 groups of publishers with different traits:

Money Makers – traditional publishers with the biggest market share, the highest number of articles published, APC set to the highest they think market can bear without losing submissions, initially offering biggest discounts for institutional deals to get sign ups (and easier access to authors).

Prestige reputation – traditional publishers trading on their reputational status. Significantly less articles published but with larger APCs levied to publish in the journals with the highest impact factors. Strategy of selling high end products and services to those that can afford them.

Emerging challengers – new business model and products, more reasonable APCs to attract a market share. However, it is worth noting that since being bought out by Springer, BMC have attracted criticism for raising APCs much quicker than the rate of inflation.

When we get round to submitting the final RCUK report we’ll release our full dataset of article processing charges.

[Minor edits made to original to correct grammar, headings and stylesheet]

Chrystal Macmillan Lecture: Professor Veena Das reading list

On Wednesday 18th June 2014 Professor Veena Das will deliver this year’s Chrystal Macmillan lecture.

Krieger-Eisenhower Professor at John Hopkins University and a founding member of the Institute of Socio-Economic Research in Development and Democracy, Professor Das is an established figure in Indian anthropology and her research interests also include feminist movements and gender studies, anthropology of violence, social suffering and subjectivity.

For the Chrystal Macmillan Lecture she will be speaking on the topic:

War and Intimate Violence: Reading the Ethnographic Record in the Light of the Mahabharata.

Professor Das has been published extensively and has worked as an editor on a number of publications. Using Resource Lists @ Edinburgh we’ve put together a Professor Veena Das reading list with just a small selection of books and articles authored or edited by Professor Das that University of Edinburgh staff and students can access through the University Library.

Professor Veena Das reading list

For more information on the 2014 Chrystal Macmillan lecture and how to book see:

Professor Veena Das to deliver 2014 Chrystal Macmillan lecture

For previous lectures see: Chrystal Macmillan lectures

Caroline Stirling – Academic Support Librarian for Social and Political Science

Collections

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Projects

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....