Home University of Edinburgh Library Essentials

April 18, 2024

AI, Theological Libraries … and me

The University of Edinburgh hosted the Association of British Theological and Philosophical Libraries conference this year at New College on 21-23 March. As usual there was the opportunity for discovering fascinating and historic libraries, including (of course) New College Library, the National Museum of Library of Scotland and the Signet Library.

Computer17293866, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

A key focus this year was Artificial Intelligence or AI, and Prof Nigel Crook from Oxford Brookes University opened the conference, speaking about ‘Generative AI and the Chatbot revolution’, and concluding that while he didn’t predict a future like the one in the Terminator, this couldn’t entirely be ruled out. 😊 Following this was Professor Paul Gooding from the University of Glasgow, with an engaging talk on ‘Applying AI to Library Collections’. He identified a key challenge for libraries as being the control of AI development by a handful of technology firms – the forces driving AI tools are not situated in the library sector. How can libraries play a part in AI innovation? Read More

Research and the One Health Archival Collections

Hello, I’m Elizabeth, the postdoctoral researcher on the One Health archival project! During the Wellcome Trust grant, I was employed for five months from October 2023 to the start of March 2024 to develop academic engagement with the archival material and undertake a short research project. Thanks to funding from Heritage Collections, I can continue for two more months until early May, focusing on engagement and another short research project. I will spend the next month blogging to introduce research strands identified across the collections that might be of interest to researchers/students, share short research projects I’ve undertaken, and our academic engagement activities so far. By doing this, you’ll really get a flavour for the richness of the collections as a resource for research.

RZSS Animal Arrival and Death Records

Just a quick introduction to my background! I have a PhD in environmental policy and ethics, with focus on biodiversity conservation, but more recently I have undertaken degrees in anthropology, in the subfield of anthrozoology, where we study human-animal relationships and interactions, considering socio-cultural, political contexts. My previous research projects have primarily involved captive wild animals in zoos and circuses, compassionate conservation and human-wildlife conflict and coexistence. I had previously undertaken research on Charles Darwin that introduced me to digital archival research, but I had not engaged directly with archival material – this is an exciting, new world to be immersed in. Thank you to Fiona Menzies, Project Archivist and lead, for introducing me to it!

Me and my cat, Reilly, who is known well at the Dick Vet due to his many rare health conditions!

The archival materials are fascinating in so many respects, windows into specific organisations in Edinburgh and how they were located within wider debates in Scotland and the UK about animal health, welfare, conceptions of animal cruelty, public health and the roles and perceptions of women in caring within communities, for instance. More on research possibilities in the next blog post! In the meantime, do get in touch if this post has already piqued your interest: you can comment on the blog post or reply to me directly at elizabeth.vandermeer@ed.ac.uk.

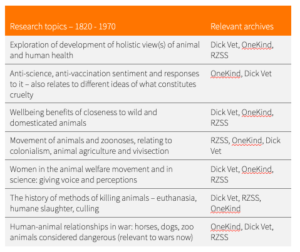

Sneak peak at research strands:

Research streams that cross the collections

Systematic Reviews: five frequently asked questions

When the Academic Support Librarians provide help for students and researchers who are conducting large-scale reviews, such as systematic and scoping reviews, we find that often the same questions will come up. This blog post aims to answer five of your frequently asked questions about systematic reviews and provide some useful resources for you to explore further.

For even more advice about systematic review guidance, see the library’s subject guide on systematic reviews and LibSmart II: Literature Searching for Systematic Reviews.

Now let’s dive in to five Frequently Asked Questions…

1. What is a systematic review, and how does it differ from other types of literature review?

According to the Cochrane Collaboration, a leading group in the production of evidence synthesis and systematic reviews;

systematic reviews are large syntheses of evidence, which use rigorous and reproducible methods, with a view to minimise bias, to identify all known data on a specific research question.1

This is done by a large, complex literature search in databases and other sources, using multiple search terms and search techniques.

Traditional literature reviews, such as the literature review chapter in a dissertation, don’t usually apply the same rigour in their methods because, unlike systematic reviews, synthesise all known data on a topic. Literature reviews can provide context or background information for a new piece of research, or can stand alone as a general guide to what is already known about a particular topic2.

What about scoping reviews?

There are other review types in the systematic review “family”3. You may have also heard of scoping reviews. These are similar to systematic reviews, in that they employ transparent reporting of reproducible methods and synthesise evidence, but they do so in order to identify knowledge gaps, scope a body of literature, clarify concepts or to investigate research conduct4. Literature searching for scoping reviews will be similarly comprehensive, but may be more iterative than in systematic reviews.

Useful resources:

- Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J, 26(2), 91-108.

- Munn, Z., Peters, M.D.J., Stern, C. et al. (2018) Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol 18, 143.

2. Which databases should I use?

Image by AcatXIo • So long, and thanks for all the likes! from Pixabay

Choosing appropriate databases in which to search is important, as it determines the comprehensiveness of your review. Using multiple databases means you are searching across a wider breadth of literature, as different databases will index different journals.

The list of Databases by Subject and the library subject guides can guide you to key databases for your topic.

To get an idea which databases are best suited to yield the data you need, you can also look at published systematic reviews on similar topics to yours, to see which databases those authors used.

The number of databases you use to search will vary depending on the research query, but it is important to use multiple databases to mitigate database bias and publication bias. More important than the number of databases is using the appropriate databases for the subject to find all the relevant data.

Useful resources:

3. What is grey literature and how do I find it?

Image by OpenClipart-Vectors from Pixabay

You may have read that you should include grey literature in your sources of data for your review.

The term ‘grey literature’ refers to a wide range of information which is not formally or commercially published, and which is often not well represented in library research databases.

Using grey literature will help you to find current and emerging research, to broaden your research, and to mitigate against publication bias.

Sources and types of grey literature will vary between research topics. Some examples include:

|

|

Key sources of grey literature

Finding grey literature can be tricky because it can vary a lot in type and where it’s published. To help you, the Library’s subject guide has some key sources of grey literature to explore. The Library also has several databases which include records of dissertations and theses, which can be a source of relevant data for your review.

Another useful approach is using a domain search in Google to search within the websites of key organisations or professional bodies in your subject. For example, searching site: followed by a domain in Google:

site:who.int will search within the WHO website.

site:gov.uk will search only websites with a url that ends .gov.uk

4. How do I translate searches between databases?

Image by 200 Degrees from Pixabay

You may have heard that you need to ‘translate’ your search. This simply means taking the search you have developed in the database and optimising it to work best in a different database.

The way you tell a database to search for a term in the title of the record, or the command for searching for terms in close proximity to each other, will be different between databases and platforms.

For example, in the medical literature database Ovid Medline, the search for a subject heading on gestational diabetes is Diabetes, Gestational/ whereas the nursing database EbscoHost CINAHL uses MH “Diabetes Mellitus, Gestational”. Both the syntax that refers to a subject heading needs to be translated (/ to MH) and the subject heading itself is different (Diabetes, Gestational to Diabetes Mellitus, Gestational).

You can practice translating a search in the Learn course LibSmart II in the module on Literature Searching for Systematic Reviews. We also have a Library Bitesize session on translating literature search strategies across databases coming up in April.

Useful resources:

- Polyglot search tool: A tool for translating search strings across multiple databases.

- Database syntax guide [PDF] by Cochrane

5. Do you have any training for systematic review?

Image by José Miguel from Pixabay

We do! The Learn course LibSmart II: Advance Your Library Research has a whole module on Literature Searching for Systematic Reviews. LibSmart II can be found in Essentials in Learn. If you don’t see it there, contact your Academic Support Librarian and we’ll get you enrolled.

We also have several recorded presentations on systematic reviews on our Media Hopper channel, including ‘What is a systematic review dissertation like?’ and ‘How to test your systematic review searches for quality and relevance’.

For self-paced training on the whole process of conducting a systematic review, Cochrane Interactive Learning has modules created by methods experts so you build your knowledge one step at a time. Perfect for what can be an overwhelming research method.

If you are a student conducting a systematic review, we can highly recommend the book Doing a Systematic Review (2023). With a friendly, accessible style, the book covers every step of the systematic review process, from planning to dissemination.

—–

The FAQs in this post are taken from the library subject guide on Systematic Review Guidance where you can find even more information and advice about conducting large-scale literature reviews.

You can contact your Academic Support Librarian for advice on literature searching, using databases, and managing the literature you find.

—–

References

- Higgins, J., et al., Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.4 (updated August 2023). 2023, Cochrane.

- Mellor, L. The difference between a systematic review and a literature review, Covidence. 2021. Available at: https://www.covidence.org/blog/the-difference-between-a-systematic-review-and-a-literature-review/. (Accessed: 20 March 2024).

- Sutton, A., et al., Meeting the review family: exploring review types and associated information retrieval requirements. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 2019. 36(3): p. 202-222.

- Munn, Z., et al., Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol, 2018. 18(1): p. 143.

Call for papers: Esther Inglis in contexts and culture, 19th-20th October 2024

The University of Edinburgh is delighted to invite proposals for a colloquium on the contexts and cultures surrounding the work of Esther Inglis (c.1570-1624), which will be held at the University of Edinburgh on the 19th and 20th October 2024. Guest speakers will include Dr Georgianna Ziegler (Folger Shakespeare Library) and Dr Jamie Reid Baxter (University of Glasgow)

Esther Inglis (c.1570-1624) is a uniquely important scribe, writer and artist.

Escaping religious persecution in France, she and her family moved briefly to England before settling in Edinburgh during her early childhood; here she acquired the skills in calligraphy, drawing, and embroidery that combined to create the extraordinary manuscript books for which she is still famed. Inglis was highly praised as a scribe in her own day, sometimes called the ‘mistress of the golden pen’, and the regard in which her skills were held allowed her books to play a role in the pursuit of personal, religious and political interests. Inglis’s work is not unfamiliar to both academic and wider audiences today, and she continues to inspire contemporary writers and artists. But much remains to be done to understand the multiple forces and contexts which shaped her activity and her singular place within the culture of her time — from her relationship with Scottish politics, to her experience as a Huguenot refugee.

In the quatercentenary of her death, the University of Edinburgh, with the support of the University of Leiden, is hosting a colloquium on the 19th and 20th October 2024, to bring together researchers working on any aspect of Esther Inglis’s life and work, and on any of the crafts, media and cultural contexts in which she worked.

We welcome proposals for 20 minute papers in any of the following areas of early modern study relevant to Inglis:

Scribal culture and manuscript production in an age of print

The practice of book making

Art and the making and giving of gifts

Craft skills and cultural production

Religious and/or cultural politics in early modern Scotland, France, and England

Women’s writing and women’s authorship

Translation and transmediation

Transnationality and the culture and politics of refuge

Proposals (max 200 words) should be sent to Inglis400@ed.ac.uk by 31st May 2024.

Download this call for papers as a PDF here: Esther Inglis contexts culture 24

This colloquium is part of a project that has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 864635, FEATHERS). Read more about the project here. This colloquium is organised in collaboration with the ongoing “Esther Inglis 2024” project at Edinburgh University Library.

Images copyright Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, and Folger Shakespeare Library, licensed under CC-BY-NC 4.0; copyright National Library of Scotland, reproduced with permission.

Meet the manuscripts — and what to do with an “Inglis manuscript” which is not by Esther Inglis

This blog post introduces the six manuscripts written by and associated with Esther Inglis which are held at Edinburgh University Library. The cataloguing, conservation, and digitisation of this manuscript group forms an important output of “Esther Inglis 2024”. This post is written by the Project Curator.

Today, sixty-three manuscripts by Esther Inglis are known worldwide. This number includes manuscripts which are currently held in libraries or in private collections. It also includes manuscripts which are recorded in older auction catalogues or described in historical records. The total of sixty-three known Esther Inglis manuscripts is the highest it has ever been, but this number is constantly shifting. In 2012, two manuscripts previously considered Esther Inglis’ work were de-attributed in a new catalogue drawn up by Nicolas Barker. These manuscripts are now thought to be compilations of sixteenth-century calligraphic pieces which were gathered together by later owners. One of these manuscripts is in the National Library of Scotland — MS 2197. The other is MS La.III.522, held by the University of Edinburgh. So where did this original attribution to Esther Inglis come from, and how does it relate to the other five manuscripts in the University which she definitely did write?

The six Inglis-related manuscripts at the University of Edinburgh all came to the Library at the bequest of David Laing (1793-1878). Laing was a Scottish antiquary, a collector of manuscripts and a bibliographer. At his death, Laing left his manuscript collection to the University; the Laing collection is the largest single manuscript collection in the University Library. Laing was an important early collector of Esther Inglis’ manuscripts; in 1865, he published “Notes relating to Mrs Esther (Langlois or) Inglis, the celebrated calligraphist” in the Proceedings of the Society of Antiquarians of Scotland. Today, this extensive article continues to be cited by modern scholars as a source of bibliographical information not only for Esther Inglis, but also for her father Nicolas Anglois, husband Bartilmo Kello, and father-in-law John Kello. Laing’s article also describes 28 manuscripts by Inglis which he has either seen, heard of, or owns. Five of the six Inglis-related manuscripts now at the University of Edinburgh are included in this list; these are: MS La.III.440, MS La.III.439, MS La.III.75, MS La.III.525, MS La.III.522.

David Laing continued to collect manuscripts by Inglis after publishing his 1865 article; the manuscript now MS La.III.249 includes a note in Laing’s handwriting to say that he acquired it in 1867. The rest of this blog post will introduce this group of six manuscripts, which form the part of the core of the “Esther Inglis 2024” project.

Read on to meet the manuscripts…

La.III.440

This is one of Esther Inglis’ earliest dated manuscripts, produced in 1592. It contains the text of the hundred verses entitled De la grandeur de Dieu et de la cognoissance qu’on peur avoir de luy par ses oeuvres [On the greatness of God, and on the knowledge that one can have of him through his works], originally written by Pierre du Val and published as a printed book in 1553. Forty years after this first publication, Esther Inglis’ copies of these verses are intricate and decorative; she rewrites these hundred verses in twenty different styles of script, which vary dramatically in size and ornamentation. Esther Inglis’ manuscript has an oblong format; this is unusual for its time, but is likely to reference the shape of sixteenth-century handwriting manuals or “writing books”, which were designed to be laid flat on a table. However, Inglis’ manuscript measures just 9 by 12 centimetres, much smaller than any writing-book she might have seen. This little book draws its viewer in to new worlds of writing, through which to read the wonders of creation described within its text.

La.III.525

This manuscript is an example of a “friendship album”, or album amicorum, kept by the Edinburgh-born George Craig. An album amicorum collects signatures or inscriptions by individuals, perhaps friends of the album’s owner, or those who the owner met on their travels. On the 8th August 1604, Bartilmo Kello and Esther Inglis both added inscriptions to Craig’s album while they were in London. These inscriptions are facing each other, and offer a striking comparison between the scribal hands of husband and wife.

Folios 7v-8r of MS La.III.525

La.III.249

This manuscript is a rare example of Esther Inglis working on a scribal commission; it is a copy of of Book 2 of the Latin ‘Treatise on Union’ composed by David Hume of Godscroft (1558-c.1630). Written in 1605, the manuscript is a presentation copy which Hume may have intended to present to King James VI/I and Prince Henry Frederick, as the dedicatees of this work. Although her name is not written in this manuscript, Esther Inglis’ calligraphy is clear from both the quality of its script, and her subtle floral decoration.

Title-page of MS La.III.249

La.III.439

This manuscript, produced by Esther Inglis in 1606, contains a copy of the popular religious and moral Quatrains written by Guy du Faur, Seigneur de Pybrac. In 1607, Inglis gave her manuscript as a gift for the New Year to Robert Cecil (1563-1612), 1st Earl of Salisbury. Like many of the books made by Inglis between 1600 and 1608, this manuscript has a richly illuminated title-page with a floral border (see this blog post), and each of its calligraphic verses would originally have been accompanied by individual botanical decorations. This particular manuscript of Quatrains, however, has been subject to the collecting or collaging activities of a later reader; with just four exceptions, all of these botanical decorations within the main text have been cut out. The manuscript makes for a fascinating record of the changing value judgements which have been placed upon this miniature book in the centuries after its production.

La.III.75

This manuscript is a collaborative production between Esther Inglis and her husband, Bartilmo Kello. The couple produced this manuscript in 1608 as a gift for Sir David Murray of Gorthy, thanking him for having secured the position of rector for Bartilmo Kello in the parish of Willingale Spain, in Essex. The text is Kello’s English translation of Yves Rouspeau’s Traitté de la préparation à la saincte Cène de Nostre seul Sauveur et Rédempteur (1563); Kello titles his version A Treatise of Preparation to the Holy Supper and of our only Saviour and Redeemer Jesus Christ. Esther Inglis copies this text into her manuscript in scripts which closely imitate a printed book. Part of the intrigue of this manuscript lies in its print-like appearance, from its words to its layout, and this replication (or perfecting) of print is a technique which Inglis continues to develop across her career.

Title-page of MS La.III.75

La.III.522

MS La.III.522 is not written by Esther Inglis herself, but instead is a composite manuscript of pieces assembled by a later collector. It contains several different collections of calligraphy samples now bound into one. Two of these collections follow the aspect and structure of early-modern writing-books; two decorative alphabet structure samples of writing in different kinds of script. One of these decorative alphabets is composed of gothic, knotwork intials, as shown below. Scripts and decoration are embellished with gold ink; these writing-books were presumably not produced as teaching samples, but to demonstrate the skills of particular writing masters.

Gothic initials accompanying the calligraphy samples in MS La.III.522

These alphabetised calligraphy samples, however, have since been bound with other materials. Nicolas Barker’s suggestion is that the compilation was made by Archibald Constable, whose son David Constable (1795-1857) later sold the manuscript to David Laing on the 18th December 1828. None of the items in the manuscript are dated, but several names of possible scribes appear. One section of its calligraphic pieces bears the name Jacques Dorsanne, and is dedicated to Philippe de Mornay (1549-1623), a Huguenot writer and supporter of Henry IV of France. Two further pieces, meanwhile, are signed by a William Geddie (d. 1624), a scribe who worked “at Barnetoun” [Barnton], in the outskirts of Edinburgh.

Ornamental frame and miniature writing by “M.W.Gedde” (William Geddie), MS La.III.522

As Jamie Reid Baxter has shown, it is very likely that William Geddie was a relative of John Geddie, a scribe connected with the court of James VI. John Geddie is known to have copied a manuscript of George Buchanan’s poem De Sphaera [On the Sphere], which then passed to William Geddie. David Laing certainly thought that there was a connection between these two scribes; on the inner cover of this manuscript, he has added a transcription of a record from the 8th May 1577, which awards a yearly pension from George Buchanan to “his lovit Mr Johne Geddy”. As Jamie Reid Baxter and others have noticed, there are in turn clear connections between the style of decoration used in a presentation manuscript made by John Geddie for James VI in 1586, and the decorative borders and initials found in Esther Inglis’ own manuscripts produced between 1599 and 1602. This connection strongly suggests that Inglis herself knew John Geddie, and both Geddie scribes may have been part of her circle in late sixteenth-century Edinburgh.

Signature and inscription of David Laing on inner front cover, MS La.III.522

When David Laing published his description of this manuscript in 1865, he also noted the presence of one important document bound into the collection which has sadly since been lost. This document is a draft “warrant” which, had it ever been signed, would have appointed Bartilmo Kello to the position of “clerk of all passports” under King James VI/I. The text of this warrant also makes reference to “the mest exquisit wreater [writer] within this Realme” who was to assist in the writing of official documents under King James — Esther Inglis herself. The fact that Inglis herself is not named directly strongly suggests that her writing was already known within royal circles. By 1596-7, when this warrant is likely to have been drafted, neither she nor her calligraphy needed any introduction.

The presence of this draft warrant, together with the calligraphic nature of the rest of the items bound within this manuscript, presumably combined to invite David Laing’s attribution of MS La.III.522 to Esther Inglis in his 1865 “Notes” — an attribution which endured for the next 147 years. But the question remains whether the subsequent deattribution of this manuscript decreases its value or scholarly interest. And does this deattribution mean that MS La.III.522 has become less significant for the work of the “Esther Inglis 2024” project?

Far from it. As Project Curator, my own view is that Esther Inglis’ calligraphy can only be fully understood or appreciated when it is set alongside the productions of other scribes working in similar circles. MS La.III.522 contains the handwriting of other scribes working in and around Edinburgh at the same time as Inglis. How else can audiences measure the differences of what Inglis herself writes and draws, the influences which she calls upon, and the artists or writers to which she responds, if her work is not examined alongside the productions of these wider contexts? The contents and history of MS La.III.522 offer just such a touchstone against which to set Esther Inglis’ own manuscripts, the better to understand the exceptionality of what she, as a rare woman calligrapher known within the royal court, was able to accomplish.

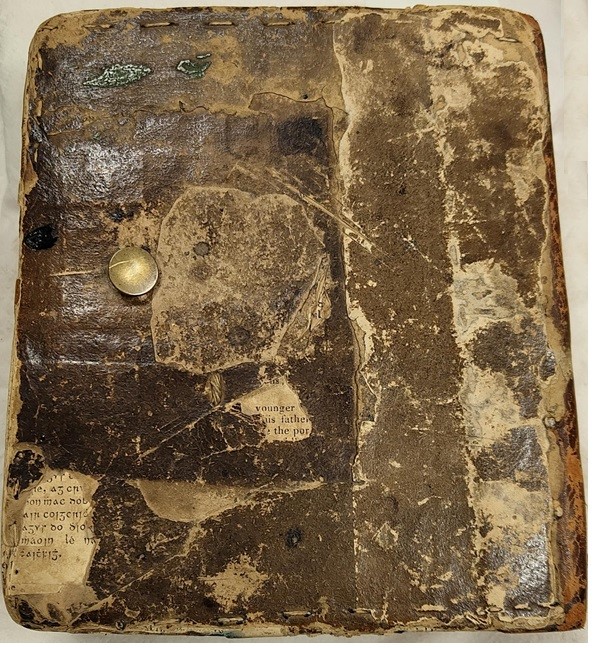

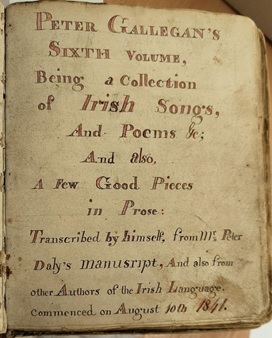

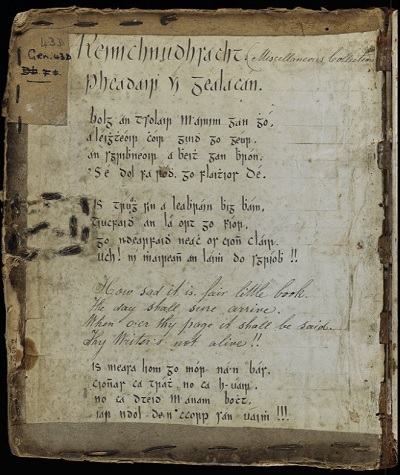

Peter Gallegan’s Collection of Irish Songs and Poems

To mark St Patrick’s Day, we thought we’d highlight a remarkable volume of Irish songs and poems that is in the University’s donated collections (ref. Coll-1366). The book was copied and compiled by Peter Gallegan or Peadar Úi Gealcáin (1792-1860) who was a scribe and a hedge school teacher in Moynalty parish, in County Meath.

- Back cover of Peter Gallegan’s book. Note the button for fastening a cord (no longer extant) to keep it shut and printed Irish paper underneath the worn leather as part of the binding. (Coll-1366)

- Title page of Peter Gallegan’s book.

It comprises about 700 pages, containing some 260 items in Irish, sometimes translated into English, and, as you would expect for a scribe, it is skilfully written. Gallegan always writes Irish in Irish script, English in cursive hand and titles in red ink. Some items are composed or translated by Gallegan himself and others were collected from local bards. In the main, the items are centred around love or patriotism and are often humorous or allude to characters from the classics. As with many collectors of that era, he endeavours to give biographical information on the composers and any background information on the subject matter. The following was composed for a young woman called Bridget.

Song entitled Réult na Maidne [The Morning star] Brighdin Padruic [or] Bridget Fergus. (Coll-1366, p. 355)

‘This is a Mayo song, Bridget lived about

the middle of the 17th Century, and was the

most beautiful female in Connaught. Her

father resided at Rohard, near Ballinrobe,

in Mayo, the song was the Joint Composition

of two contemporary bards, McNally & Fergus,

the latter having composed the 3rd. & 4th. Stanzas.’

The care with which Gallegan copied the material indicates the value he saw in its preservation. On one page (p. 488) he wrote:

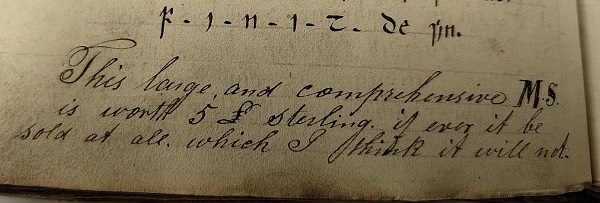

Coll-1366, p. 488

‘This large, and comprehensive M.S.

is worth 5 £ Sterling, if ever it be

sold at all, which I think it will not.’

Unfortunately, Gallegan’s employment as a teacher was precarious and he had to move schools quite regularly to maintain an income (see Dictionary of Irish Biography). In the end, his poverty obliged him to sell the books he’d compiled.

Throughout the volume Gallegan regularly wrote notes about himself asserting his position as the scribe of the volume, in some ways indicating a sense of his own mortality in comparison to the book’s own anticipated longevity.

IS truagh sin a leabharain bhig bháin

Tiucfaidh an lá ort go fíor

Go ndearfaihd neach os cionn cláir

Uch! ní mairean an láimh do sgriob!!

How sad it is fair little book,

The day shall sine arrive,

When o’er thy page it shall be said

Thy Writer’s not alive!!

(Coll-1366, inside front cover)

As for its provenance, this volume came from the library of Eugène Guilford Finnerty (d. 1888) (see Calendar of Irish Wills, 1889). Finnerty passed it to the ‘Hon[ora]ble J Abercrombie’, i.e., probably John Abercromby, 5th Baron Abercromby (1841-1924), and, although there is no known record of it, it looks like it was Abercrombie who donated it to the University of Edinburgh. Finnerty wrote on the final page that it was one of sixteen volumes Gallegan gave him in return for ‘some little kindness’. He adds (p. 702):

‘I doubt much if any of our National School=

masters have the talent perseverance or patriotic feeling

that this poor poor fellow possessed. I trust that

I have to a certain extent rendered him independent

and happy in his latter days without his applying

to any society whatever for his support (of which he

had the greatest abhorrence).’

Other similar volumes by Peter Gallegan are now held in repositories like University College Cork, the Royal Irish Academy, University College Dublin and Queens University Belfast, institutions a far cry from hedge school origins, but where they deservedly take their place among the richness of Irish cultural traditions.

Lá Fhéile Pádraig sona daoibh! – Happy St Patrick’s Day! – Là Fhèill Pàdraig sona dhuibh!

Kirsty M Stewart/Ciorstag Stiùbhart, Scottish and University Collections Archivist

Resource Lists: What do you think? We want to know!

We’re in the midst of gathering feedback about Resource List use within the School of Law and would like to invite our students to get involved in a short focus group that will help us shape our approach to lists in the future.

If you’re available on Wednesday 17 April 2pm to 4pm and will be in Central Edinburgh then please email our project manager Karen to register your interest.

Tea, coffee and cake will be provided and participants will receive a £10 gift card for Blackwells, which can be used to purchase any of their worldly goods (including books, games, stationery and much more!).

There are eight spaces available. The focus group will take the form of informal discussion with some structured questions about whether or not you use the List system, what you like about it, and will give you lots of time to provide your thoughts and discuss with others in the room. All feedback will be used to inform the development of lists within the school and responses will be anonymised.

If you have any questions about the process please contact Karen Stirling by email.

(NOTE: Date changed from 26th March to 17th April to gather more participants.)

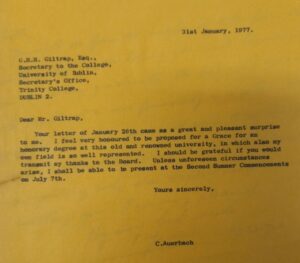

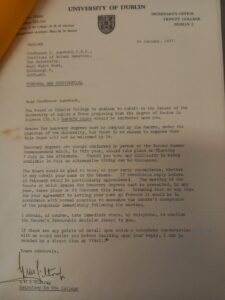

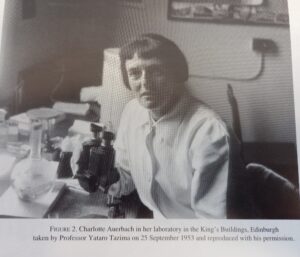

The Achievements of Professor Charlotte Auerbach

In celebration of International Women’s Day, our volunteer Ash Mowat looks to the archives to see what can be discovered about the achievements of scientist Professor Charlotte Auerbach.

In this piece I am writing to remark upon files from the University of Edinburgh’s Heritage Collections on the pioneering German geneticist Charlotte Auerbach.[1] I come at this as a volunteer and enthusiast so not with any academic expertise in here scientific field.

Charlotte Auerbach (1899 to 1994) was a German Jewish scientist, specialising in the field of genetics. [2] She was born in Krefeld Germany, and from a family with a rich heritage in academia, education and the arts. Her grandfather Leopold was a renowned physician in human anatomy, whilst her father, perhaps her greatest direct influencer of her later chosen studies, was a biologist.

A Genetics Society of America obituary of her, found in the archives, describes how she first had her interest sparked in childhood. “Her interest in Biology was kindled when by her father who took time to teach her to identify birds and plants, as well as the constellations in the night sky. Her interest in Biology was not fostered in School, however, and she received no formal instruction in the subject (in School) after she was fifteen.” Of her later time as a Lecturer at the University of Edinburgh it states “Often with little more than a short list of one word topics to guide her, she held the undivided attention of successive classes of undergraduates year after year. She spoke with authority but never minded being questioned.”

She went on to study biology and chemistry across several German Universities, excelling in her studies and commencing a career in teaching the sciences at School level. The rise of the Nazi government precipitated repeated obstacles to her rights to continue to work in education. These obstacles and the ever increasing threats posed to Jews by a brutal anti-Semitic regime persuaded her to leave Germany. She then settled in Edinburgh.

The Auerbach family tree above demonstrates the astonishing educational achievements of the extended family. Sadly, there is a tragic reference to the suspected death by suicide pact of her father’s sibling and wife in 1933, cited as brought about by persecutions of the Nazi government.

Auerbach received her PhD from the University of Edinburgh in 1935 at the animal genetics institute, where she would remain until her retirement, involved in both research and in teaching University students.

The area which was to prove her chief subject of expertise was mutagenesis, this being when an organism is affected by mutation precipitated either naturally or via an external influence, such as chemicals, x-rays or ultraviolet light etc. [3]

In a lecture given in May 1957 in New York City to the Radiation Research Society, she refers to her breakthrough work in Edinburgh in the 1940’s, kept secret until some years after the end of the Second World War, that for the first time established a direct agent for mutagenesis, that of how mustard gas can cause cellular mutations in fruit flies.

The importance in this work was to reach better understanding of and protection from mutations. Agents that could potentially cause mutations could also be essential tools in medicine, such as x-rays and radiotherapy, therefore one factor in her research was to help best identify optimum levels of exposure and dosage of any mutagens, such as to maximise the best possible treatment outcome, whilst minimising the risk of destructive damage to tissues and risk of inducing cancers.

In a paper of July 1959 entitled “a discussion of mutagenic specificity” dated July 1959, she comments, “I am an evolutionist, I believe that the DNA and the two main components are intimately and, probably, spiritually conjoined”. In describing how mutagenesis functions she states “the mutagen must enter the cell and penetrate the nuclear membrane. Once inside the cell further genetic change may affect the mutagen, which then interacts with the hosts DNA.”

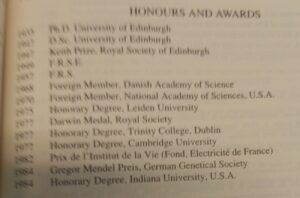

(The images above outline the granting to Auerbach of an Honorary Degree from Trinity College Dublin in 1977, one of many awards and accolades that she received throughout her life.)

Despite her many achievements I noted some instances where she could perhaps be overly self-critical of her work. In a letter to Dr Muller dated January 1946 she comments “My slow and plodding way of trying the same thing over and over again by different methods.” But later she recognises that this is surely the only way to undertake rigorous and effective science by remarking “After all, it is the only way which satisfies me and one can’t very well work in any other matter.”

Her methods were validated further in a written record of the cancer specialist Sir Anthony Haddow[4] from 1975. He observes of Auerbach “From the beginning I have had the highest opinion of Dr Auerbach’s great qualities as a researcher and teacher. In addition, I have a special reason for interest and respect, because of her pioneering in the field of chemical mutagenesis, contributions which have had an invaluable impact upon the closely related field of experimental carcinogenesis. Dr Auerbach was indeed, I believe, the first geneticist to demonstrate the mutagenic effect of chemical agents around 1940, and her method of analysis….has thrown much light on the mechanisms of gene mutation”.

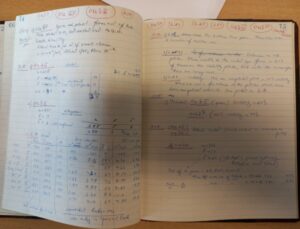

The above image from an undated hand written note book of Auerbach, further demonstrates the meticulous design of her experiments and thorough annotations. Such highly refined processes including use of control substances are essential in enabling proven results that can be replicated.

The above summary of Auerbach’s lifetime catalogue of honours and awards is evidence of the sustained expertise of her specialised field of genetics, and how widely her achievements were recognised and valued.

Outside of her academic prowess, Auerbach had a reputation for generosity and philanthropy. In a letter after her death from Professor Nicola Loprieno to Professor Geoffrey Beale at the University of Edinburgh, he remarks “I wish, apart from the great scientific contributions Charlotte Auerbach left, that everybody remembered the deepest humanity she was gifted with. I should like to point out, as I personally witnessed it, how for many years she supported through an international organisation, and an Italian youth from Sicily. She provided for his living and education, from primary school to the Scuola Tecnica Agraria. His name is Angelo Alecci. After graduation, Mr Alecci became Professor at the Istituto Tecnico Agraria. So grateful was Mr Alecci that he named one of his daughters Charlotte Auerbach Alecci.”

And Professor Beale wrote “She had a great love of children…in fact she did unofficially adopt two boys. One (Michael Avern, the other being the aforementioned Mr Alecci) was the child of a German speaking woman who lived in Lotte’s house in Edinburgh as a companion.” He notes that Auerbach left her home to Michael Avern when she moved into a care home.

In conclusion Charlotte Auerbach, or Lotte to her loved ones, devoted a lifetime of work to accomplish considerable advancements in the critical understanding of how genetics function and how such knowledge can improve healthcare. The circumstances that precipitated her having to flee Germany were obviously tragic and traumatic, however she proved to be a pioneering global asset in her chosen science. She made Edinburgh her home and a much admired and loved Lecturer at the University of Edinburgh, enhancing its prestige and bestowing her knowledge upon a whole new generation of students eager to learn from her and continue the better understanding and exploration of genetics.

[1] https://archives.collections.ed.ac.uk/repositories/2/resources/85712

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charlotte_Auerbach

Rediscovering the Poetry of Louisa Agnes Czarnecki, a 19th-Century Edinburgh Writer and Musician

Today we are publishing a blog by Ash Mowat, a volunteer in the Civic Engagement Team, on a little known 19th-century Scottish poet. The Edinburgh-born Louisa Agnes Czarnecki (née Winter) was a versatile, politically engaged writer married to a Polish political exile. Read More

Collections

Archival Provenance Project: a glimpse into the university’s history through some of its oldest manuscripts

My name is Madeleine Reynolds, a fourth year PhD candidate in History of Art....

Archival Provenance Project: a glimpse into the university’s history through some of its oldest manuscripts

My name is Madeleine Reynolds, a fourth year PhD candidate in History of Art....

Rediscovering the Poetry of Louisa Agnes Czarnecki, a 19th-Century Edinburgh Writer and Musician

Today we are publishing a blog by Ash Mowat, a volunteer in the Civic Engagement...

Rediscovering the Poetry of Louisa Agnes Czarnecki, a 19th-Century Edinburgh Writer and Musician

Today we are publishing a blog by Ash Mowat, a volunteer in the Civic Engagement...

Projects

Giving Decorated Paper a Home … Rehousing Books and Paper Bindings

In the first post of this two part series, our Collection Care Technician, Robyn Rogers,...

Giving Decorated Paper a Home … Rehousing Books and Paper Bindings

In the first post of this two part series, our Collection Care Technician, Robyn Rogers,...

The Book Surgery Part 2: Bringing Everything Together

In this blog, Project Conservator Mhairi Boyle her second day of in-situ book conservation training...

The Book Surgery Part 2: Bringing Everything Together

In this blog, Project Conservator Mhairi Boyle her second day of in-situ book conservation training...