The Association for Historical and Fine Art Photogapher’s (AHFAP) conference is always a highlight of the year and, alongside 2and3D Photography at the Rijksmuseum and Archiving, it has become one of the must-attend events for any cultural heritage imaging professional. This year we were fortunate that AHFAP took place at the National Museum of Scotland here in Edinburgh, meaning for the first time ever the entire Cultural Heritage Digitisation team could attend!

It was a great opportunity to hear about and explore some of the fascinating work being done by our colleagues across the UK and beyond: over the course of the two-day event there were many excellent speakers and workshops. Our team has put together some personal thoughts, highlights and reflections, starting with Juliette’s take on the opening keynote:

Keynote by Sophie Gerrard (Document Scotland)

Sophie Gerrard talked about her project ‘Document Scotland’, a collective of documentary photography of Scotland’s culture, landscapes and people. Initially a personal project, she now invites photographers to submit images that reflect the project’s ethos, and the group exhibit together regularly.

I enjoyed the notion of Sophie being mindful of her role within the subject matter – she considers it a serious responsibility to document the land and seemingly archaic practices (especially agricultural) that are fast disappearing. She spends considerable time with her subjects – people, spaces, landscapes and objects – in order to properly understand them. Working with medium format film, she takes photographs not only of nature, but also portraiture and still life shots inside the subjects’ homes. Capturing the ephemera may not seem important, but it is invaluable in bringing a human element to the storytelling.

Sophie presented two recent projects – the first documenting the establishment of the Trump golf course and the ensuing destruction of the protected shifting sand dunes and the lives of residents on the land. The second project was focused on female farmers around Scotland and exploring their relationship with the land. Sophie remarked that unlike male farmers who will talk about ownership, yield and profit, the women referred to themselves as custodians of the land, taking great care to keep it fertile and living. For Sophie this latter project was not only personal, but an important documentary reference of the land and objects relating to local identity and history.

Juliette

Following on from the keynote, there were several great talks including Sheila Masson from Historic Environment’s Scotland (HES) on the National Collection of Aerial Photography’s (NCAP) use of ‘cobots’ to mass digitise aerial photographs, Geoff Belknap’s on an innovative approach to engaging volunteers in digitisation projects, and an insightful overview from Iona Shepherd on her project to document the recent renovation of the Burrell Collection. The next session from was from Yosi Pozeilov, who delivered the most technical session of the day, and is described by Stuart:

Yosi Pozeilov – A Simple Ultraviolet-Induced Visible Fluorescence Target

Spectralon is a material used to create targets that help assess the ambient light level. This is a particularly important measurement when attempting to capture UV induced fluorescence images as it is important to distinguish visible light reflectance from the visible light induced by the UV light source. Spectralon is a good candidate for this due to its near perfect Lambertian reflectance and its non-fluorescence under UV light.

However, although they are initially very accurate, the targets themselves are very expensive to buy and are not particularly durable – any dirt on them or damage to the surface can throw off the measurements. While the targets can be cleaned (sanding is the recommended method), Yosi’s examples showed the process did not fully restore the essential characteristics.

Yosi was attempting to find a cost-effective alternative and noticed that, while the formulation of Spectralon was a commercial secret, it was described as a fluoropolymer in the literature. He began testing with the most common and cheapest fluoropolymer – polytetrafluoroethylene, also known as PTFE (a tape commonly used in plumbing around threaded joints) – and found its properties were very similar, while the cost was almost negligible.

He recommended using five layers of 2” McMaster-Carr tape, to get a very cheap alternative to expensive targets, creating a far more cost-effective solution.

Stuart

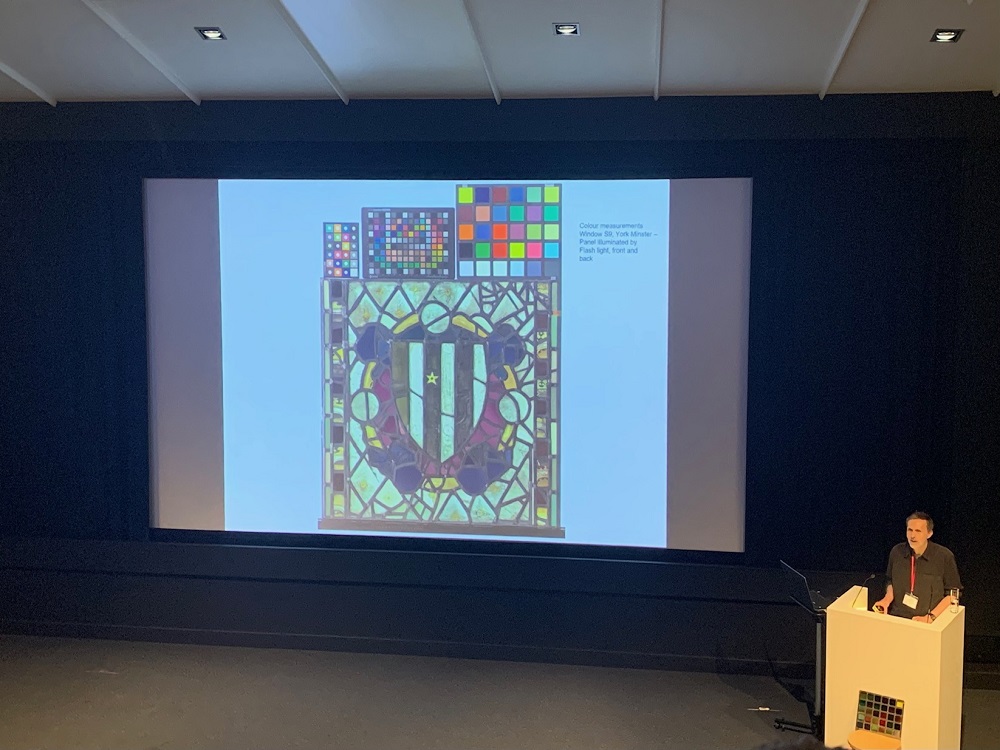

Nick Teed from the York Glaziers Trust followed Yosi’s talk, providing a fascinating overview of the challenges of photographing stained glass. Gaby reflected on his presentation:

Nick Teed – The Colour of Stained Glass

One of the highlights of this conference for me was a talk given by one of the York Glaziers Trust’s senior conservators, Nick Teed, on stained glass windows and some of the unique challenges that come with photographing them. I found that whether he was discussing the importance of documenting the condition of stained glass before and after conservation treatment or taking the opportunity to photograph aspects like fingerprints in the glaze of the glass that wouldn’t be visible with the windows in situ, there was always an underlying theme of responsibility. A responsibility to create a visual record that is as accurate and detailed as it can be.

However, one of the key points of his talk – his experiment with creating a glass specific colour checker test panel that would allow him to capture the colour of stained glass more accurately – also really demonstrated to me just how complicated this can be. While initially showing success, unique issues with the glass itself, including specific oxides used to make blue and purple coloured glass causing them to filter light differently to other colours of glass, meant that improving colour accuracy didn’t always produce images truly representative of how the windows look to the viewer.

Nick Teed’s experiment is still a work in progress, but it really got me thinking about what accuracy means when it comes to heritage photography. With collections, especially ones as visually stunning as stained glass, ensuring a faithful representation can be just as important as technical accuracy and it was fascinating to see these concepts explored during this conference.

Gaby

Nick’s talk wrapped up the morning session and was followed in the afternoon by Richard Everett from the Wellcome Trust, who gave an unforgettable overview of the varied and innovative work his photography team had undertaken over the years. Malcolm was impressed:

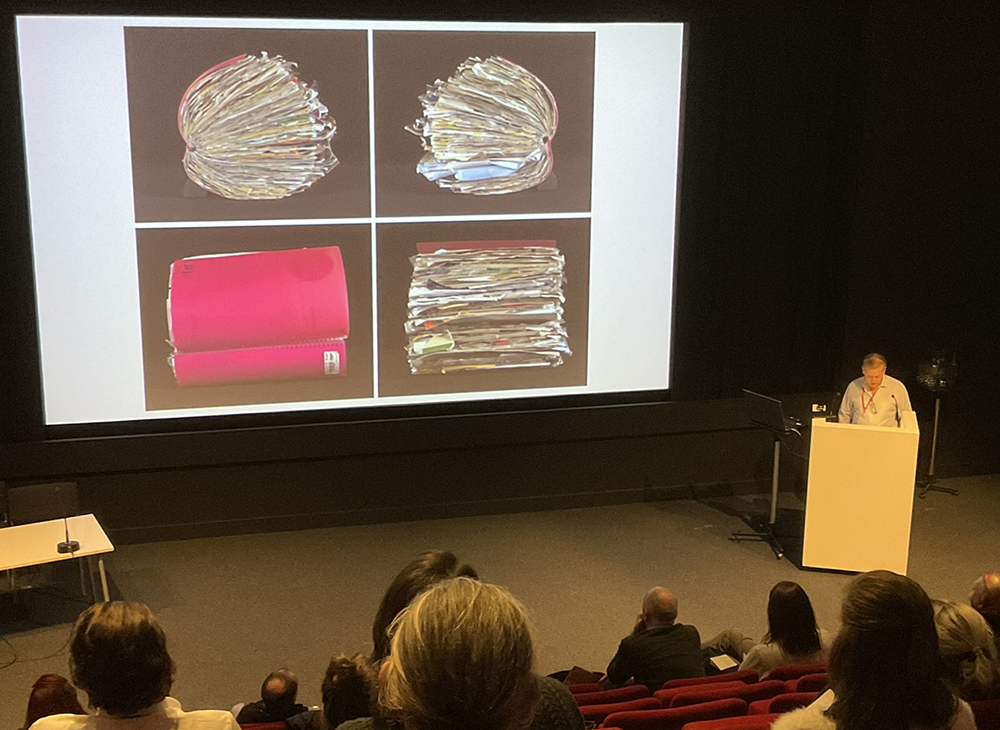

Richard Everett – Wellcome Collections a Digital Destination

This year’s AHFAP 2022 conference was outstanding in the range of talks and topics, but the one that stood out for a multitude of reasons was by Richard Everett, who presented on his journey of 30 years’ experience in heritage photography and delivery. This was echoed in the journey made by his team to research the correct models to populate Wellcome events gallery images via two modelling agencies. Having realised that the Wellcome events page online did not describe the actual events taking place, the team set out to create a page that was instantly informative. They arrived at a solution that encompassed using an agency with a diverse range of models that truly reflected their target audience and formulated a system of photographing presenters within the context of their workplace. The process of critical thinking around their own systems resulted in a stronger outcome for the Wellcome digital destination. It was that process of analysis that I found compelling from Richard and his team.

The Welcome project to photograph a collection of an artist’s (Audrey Amiss) food scrapbooks was breath-taking in its scope. The scrapbooks documented everything the artist ate each day, with food labels stuck onto every page. Food had lodged within the pages, creating mould and expanding the books to an unmanageable size. The system developed by the team to accurately capture these tomes relied on moveable custom mounts assisted by a custom-built laser guided focusing system and PPE to avoid mould inhalation. This was an almost unimaginable task brought to delivery online.

It was illuminating to hear from Richard about how he swaps the tasks assigned to his staff. His editorial team swap with the digitisation team on a two-year basis. They found that this reduced task burnout in either team. He noted that it was difficult to remain creative in the editorial team permanently and perhaps too monotonous to be digitising on a continuous basis. This role swap appears to work for the Wellcome team.

Malcolm

After Richard’s talk, Luke Unsworth gave a great overview of some of the cutting-edge technology in this field, followed by two final sessions from Margaret Weller, on the Imperial War Museum’s Digital Futures project, and Isidora Bojovic on photographing the contents of Stephen Hawking’s office.

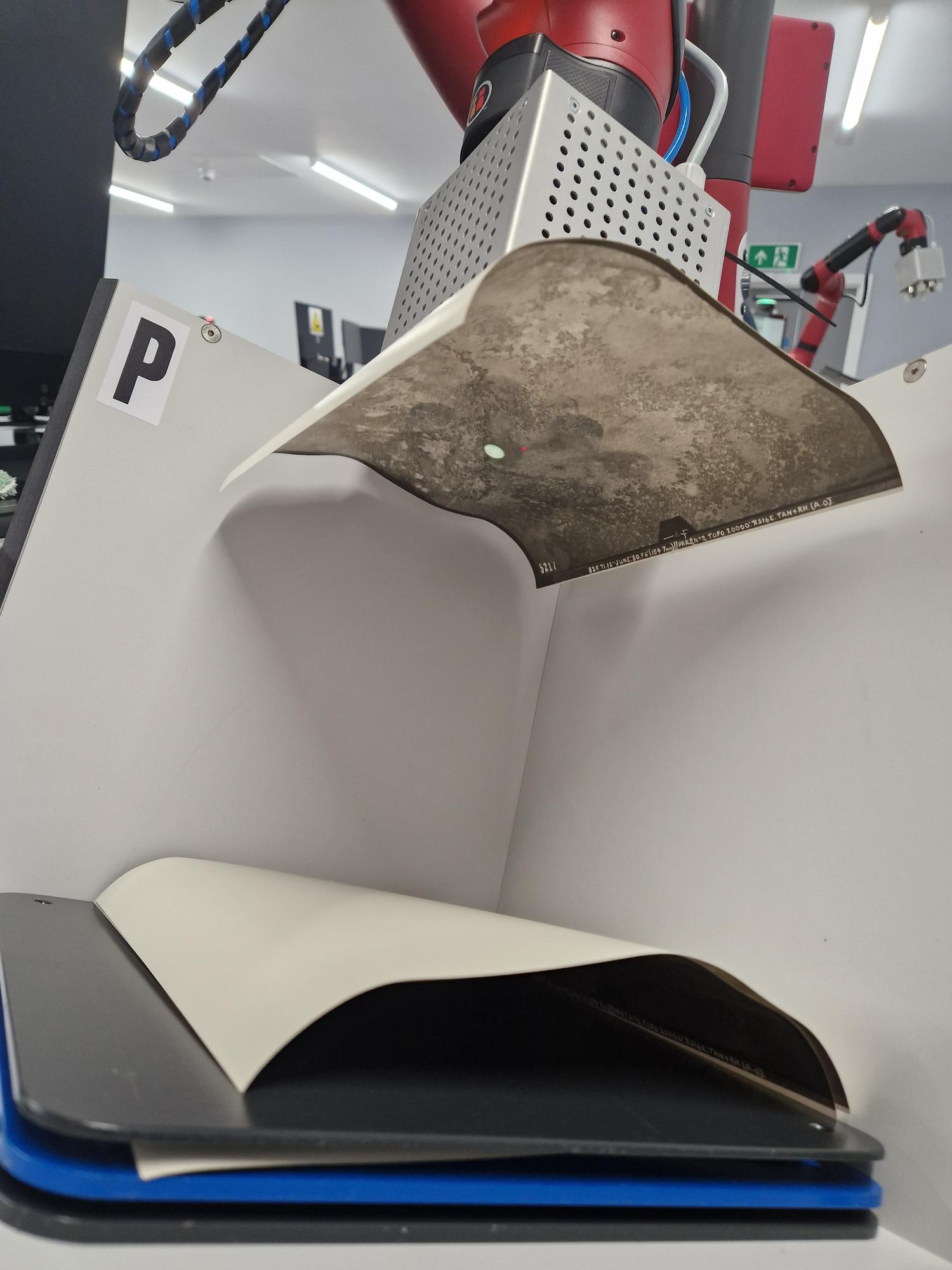

Part of the appeal of the AHFAP conference is that on Day Two there are opportunities for delegates to attend tours of nearby studios and services. Susan hosted two workshops for our team, introducing the uCreate Makerspace and demoing our new Rigster automated photogrammetry system, and other members of the team visited the Botanic Gardens, the National Museum of Scotland and other venues. Charlotte attended the NCAP tour to learn more about the ‘cobots’ mentioned in Sheila Masson’s talk on Day One:

NCAP Studio visit

There is always the worry in the back of your mind that robots will one day take over your job, but a visit to the National Collection of Aerial Photography’s (NCAP) brand-new digitisation facility just outside of Edinburgh showed us that at least for now they are happy working to digitise right alongside us. NCAP are currently utilising the skills of seven ‘cobots’, which is the preferred term as they are collaborative as opposed to fully independent. Their particular model is more commonly seen in factory production lines, but NCAP have been able to creatively program their machines, each of which of course has a distinct personality and name to go with it, to gently transfer photographic prints to and from the scanning bed.

The reason cobots are preferable to manpower alone is down to the sheer scale of the project: there are 1.5 million images to get through in the Directorate of Overseas Surveys collection and if humans were to take on the same workload it would take far longer and be physically demanding to an unacceptable and unsustainable level.

The visit was fascinating and insightful, and with the exception of the cobot (accurately, terrifyingly) named Terminator, having cobots for colleagues doesn’t seem like such a bad idea after all.Charlotte

The conference was an excellent learning experience for the team and a great chance to catch up with colleagues we hadn’t seen in person since before the pandemic. A number of themes ran throughout including the value of the profession, imaging at scale, and innovation. Gavin writes more below on the theme of people:

A recurring theme at this year’s AHFAP was that of people, specifically the invisible or hidden contributions people make to successful projects and activities across our sector and beyond.

This began with Sophie Gerrard’s inspiring work to Document Scotland, giving voice to women farmers and local residents impacted by the Trump International Golf development near Aberdeen, and continued through Iona Shepherd’s incredible portraiture of the diverse range of staff who worked behind the scenes to refurbish and relaunch the Burrell Collection in Glasgow earlier this year.

Nick Teed from the York Glaziers Trust developed this by highlighting the hidden labour that had gone into renovating the stained-glass windows from York Minster and revealed how traces of this labour lives on through fingerprints, fibres from their clothing, and graffiti and love notes etched into the glass. Geoff Belknap looked at the issue from a different angle, describing how the National Science and Media Museum’s innovative approach to working with volunteers, a group whose labour is often under-acknowledged, empowered them to make decisions about selection for digitisation, while Sheila Masson’s talk on the automation of digitisation at the National Collection of Aerial Photography (NCAP) showed us that, no matter how much value automation and robots / cobots can provide, there will always be a need for a human in the background to manage them, monitor them and clear up their mess!

Gavin

The issue of invisible labour is particularly appropriate for photographers working in cultural heritage settings, where the act of generating, managing and preserving digitised collections remains largely opaque to those working outside the field.

The team thoroughly enjoyed attending the AHFAP conference this year and would love to see the conference returning north again one day soon!

Be First to Comment