In this post book conservator Amy Baldwin talks about the conservation work undertaken on volumes appearing in the upcoming online exhibition “Rewriting the script: the works and words of Esther Inglis”.

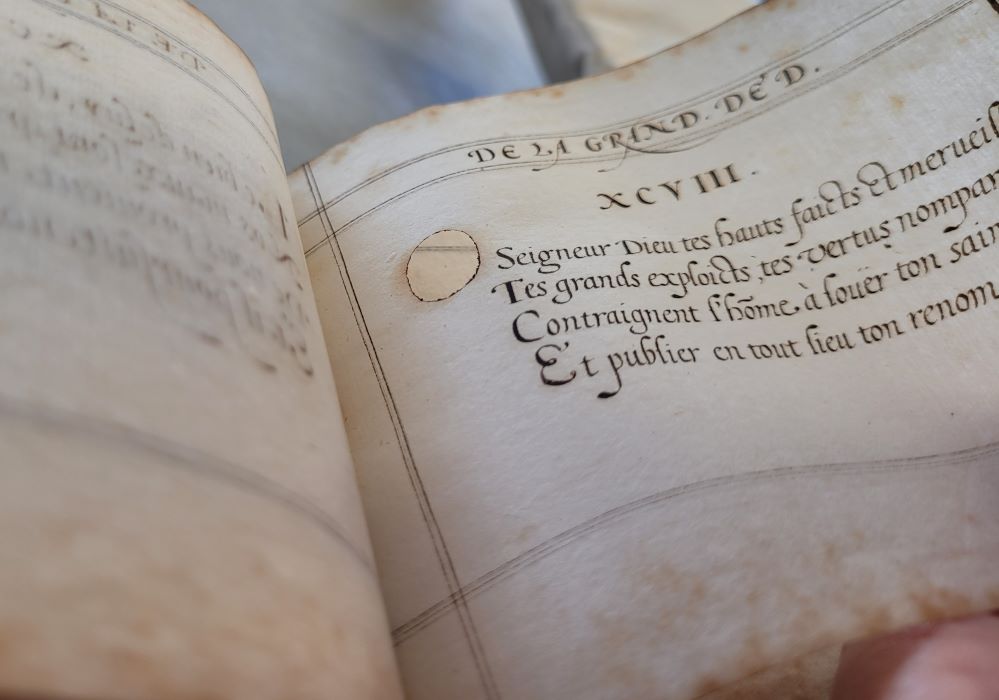

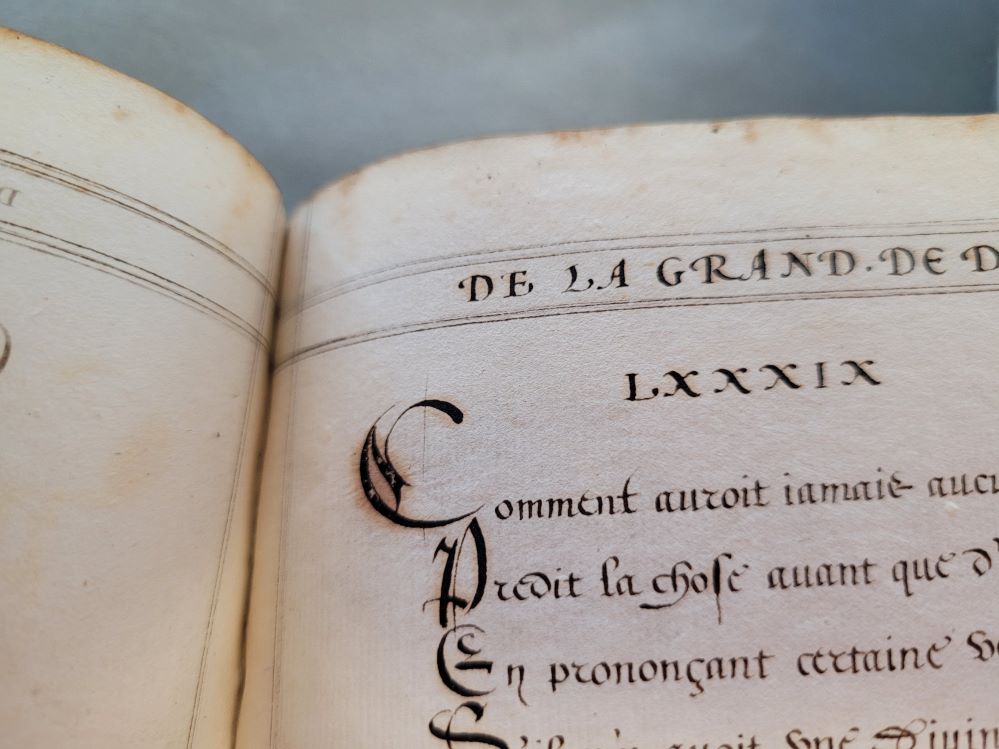

This conservation work took place as part of the “Esther Inglis 2024” project at Edinburgh University Library. 2024 marks the quartercentenary of the death of Esther Inglis (c.1570-1624), a remarkable calligrapher, author, artist, and manuscript-maker who lived much of her life in Edinburgh. 65 of her manuscripts are known to survive today, of which six are held in Edinburgh University Library. Esther Inglis’ life and works will be celebrated in an international two-day colloquium, “Esther Inglis in contexts and culture” to be held at the University of Edinburgh in October 2024 (click here to learn more about the “Esther Inglis in contexts and cultures” conference, and for registration details) . The online exhibition “Rewriting the script: the works and words of Esther Inglis” will launch in October as part of this colloquium. The six Esther Inglis manuscripts held in the University Library will be highlights of this, and they have accordingly required digitisation.

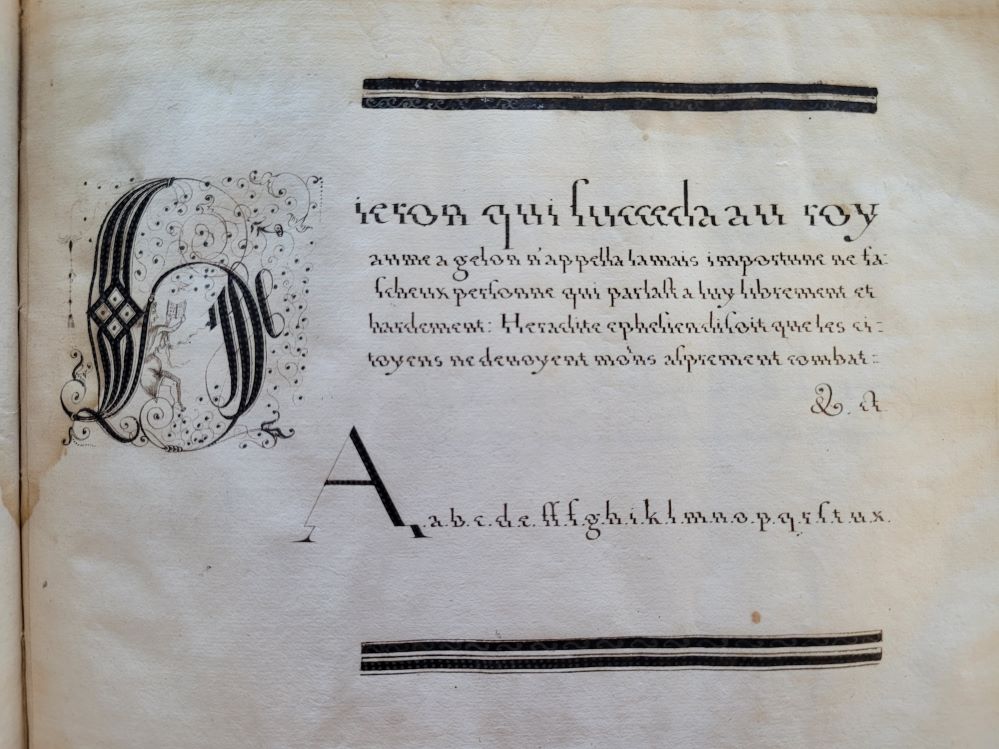

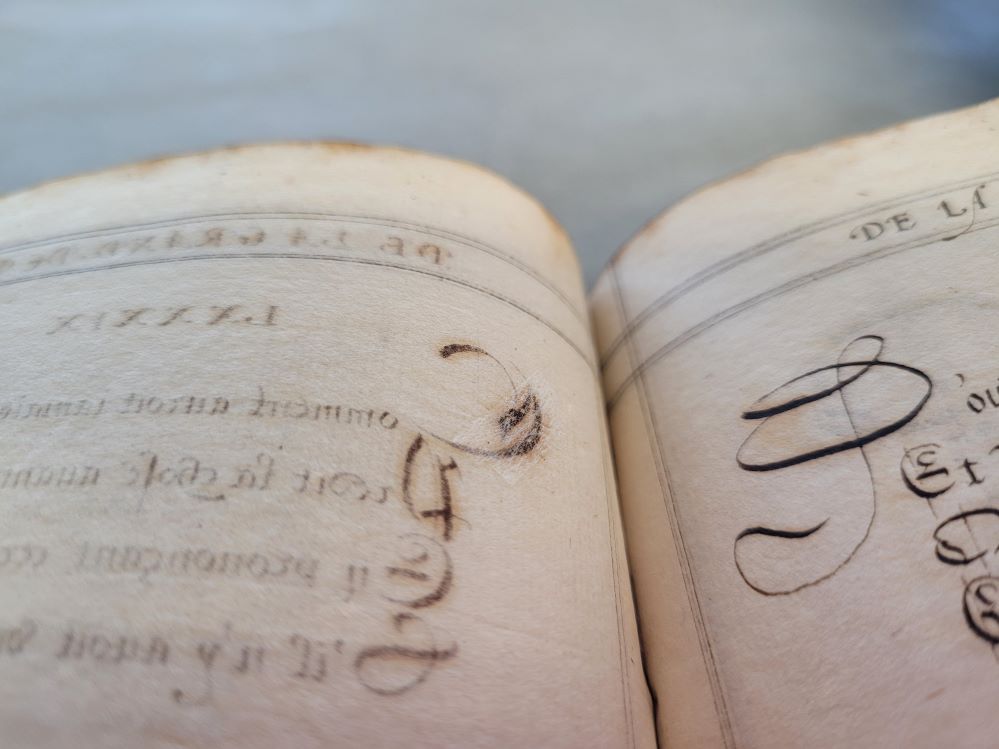

An example of Esther Inglis’ calligraphic skill: folio 10r of La.III.522

This is where I, as the University Library’s book conservator, come in! My involvement in the project began by assessing the condition of the six Inglis manuscripts and determining what conservation (if any) was necessary in order for them to be digitised safely. Digitising every page of a manuscript involves repeated handling and positioning, and vulnerable or damaged Library materials may need conservation treatment before this to prevent existing damage getting worse or new damage occuring.

The Inglis volumes posed a variety of conservation issues, ranging from small amounts of surface dirt to detached boards and missing leather. There was evidence that some had been altered and repaired already in the past, testifying to the historic popularity of Inglis’ work: torn fold-out pages had been mended with paper and glue, and some pages had been extended in order to fit the dimensions of their binding.

Old repairs to folio 30v of La.III.522

One of the features of Esther Inglis’ work which distinguished her as a calligrapher was her ability to work in multiple different forms of writing, including letters which are reversed or zigzagging, miniature writing, and imitation of print. Esther wrote these volumes in iron gall ink, which was very widely used in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. When fresh, iron gall ink is a rich, blue-black colour, but it can be chemically unstable. This results in the colour changing to brown over time and, in more serious cases, the ink can corrode the paper which supports it.

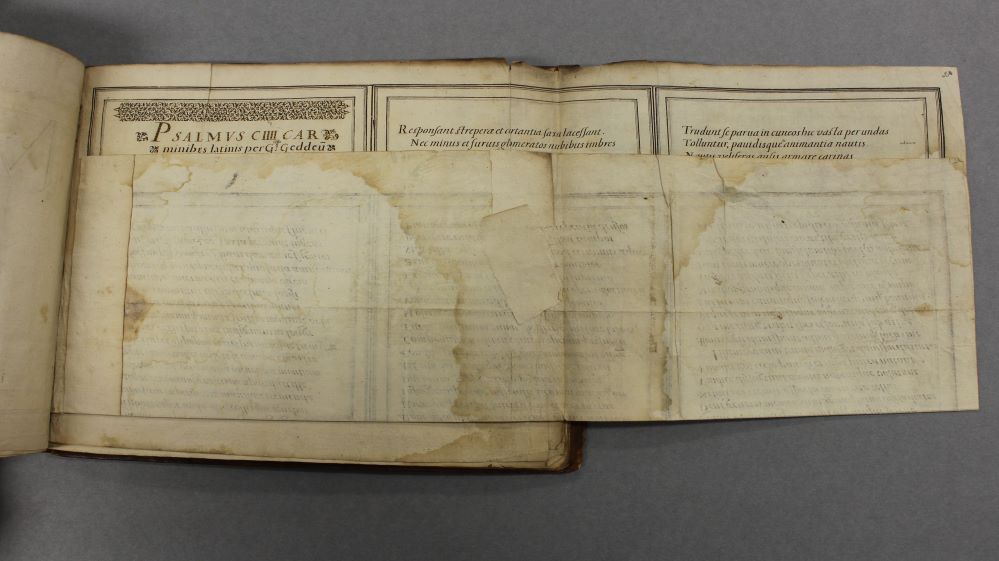

Folio 79 of La.III.440: the letter ‘O’ has fallen out due to ink corrosion.

Unfortunately, there were examples of this corrosion in manuscript La.III.440. Some areas of text had already been corroded so badly that they had fallen out of the page, while others were still in place but very vulnerable. I addressed this by attaching a very thin layer of gelatin-coated Japanese mulberry-fibre repair paper (weighing 6 grams per square metre) to the reverse of the damaged text. This holds any fragmentary pieces of ink and paper in place and prevents them from becoming lost. I chose gelatin as an adhesive because it slows down the chemical degradation of iron gall ink and should therefore extend the lifespan of the vulnerable text.

Ink corrosion visible on the recto of folio 72 of La.III.440.

Repair to corroded ink on verso of folio 72 of La.III.440.

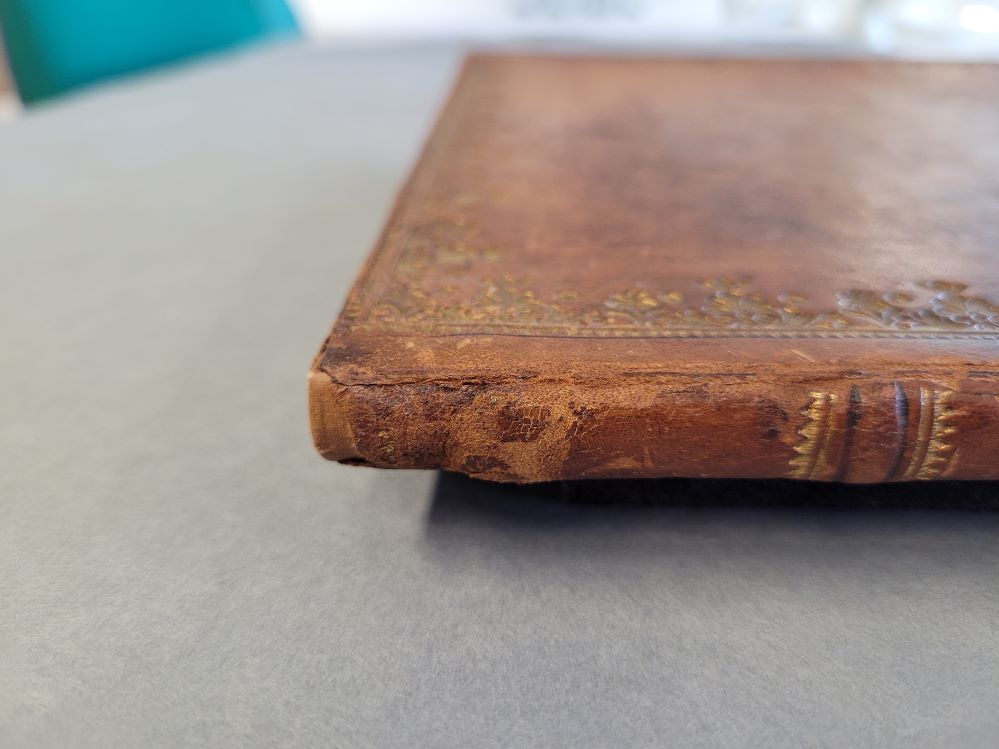

In the case of two of the Inglis volumes, the condition of the binding was of concern as well as that of the textblock. Manuscript La.III.522 was missing some of its original leather at the corners of the boards and at the head and tail of the spine. I filled these areas of loss using a heavier-weight Japanese repair paper which I toned with acrylic paints to match the colour of the original leather. I repaired with paper rather than new leather because it involved using less water-based adhesive, and old, damaged leather can blacken if exposed to moisture.

La.III.522: corners repairs drying under pressure.

Spine of La.III.522 following repair with acrylic-toned paper.

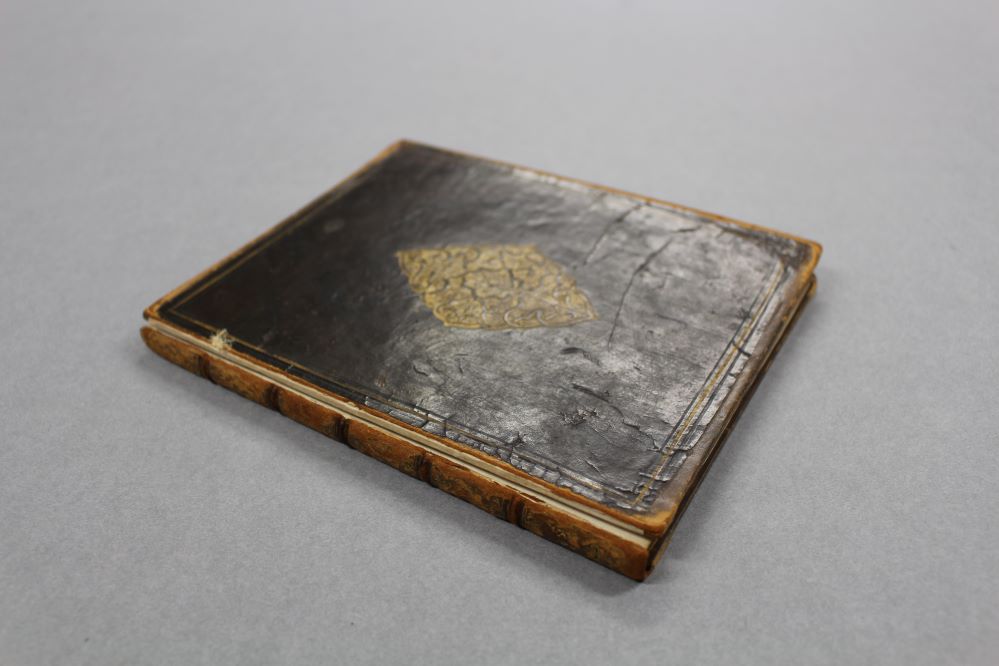

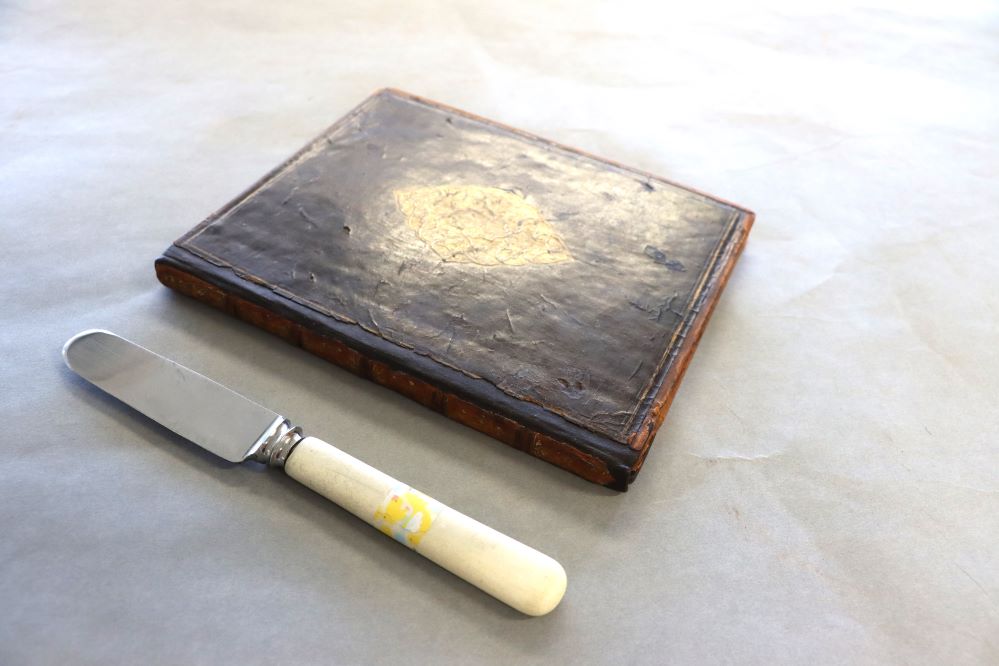

The most badly-damaged volume of the six was manuscript La.III.75. One of its boards was detached, and the leather holding the other board in place was badly degraded. To access the book’s spine and re-secure the boards I first removed the original spine leather, which came off in one piece with the help of an sharpened butter knife (a very useful tool). I reattached the boards in their original position with a piece of cotton fabric which overlapped from the exposed spine onto the insides of the boards. New leather, dyed to match the colour of the original, was attached over the spine and beneath the old leather on the outside of the boards. In this case, it was preferable to use new leather rather than paper because of its strength, as the area of the boards’ attachment to the spine experiences a lot of movement and wear. Following the treatment, the original decorative spine leather was reattached on top of the new leather.

La.III.75 before treatment.

La.III.75 after treatment, next to the sharpened butter knife.

Following conservation, digitisation of four of the volumes is now complete, and all will be available to view in the “Rewriting the script: the works and words of Esther Inglis” online exhibition from October. As well as enabling online access from anywhere in the world via digitisation, the conservation work undertaken means that these books will be accessible in person for readers and researchers to consult in the Centre for Research Collections Reading Room for years to come.

To look at the Esther Inglis manuscripts which have already been digitised, please click on the links below:

Many thanks to Anna-Nadine Pike, Curator of the Esther Inglis 2024 Project, for her help in writing this blog. Click here to read Anna-Nadine’s blog on the “Esther Inglis 2024” project.