Welcome to the Project!

This post is written by Anna-Nadine Pike, Project Curator of “Esther Inglis 2024”. Alongside this position, Anna is an AHRC-funded PhD student at the University of Kent’s Centre for Medieval and Early Modern Studies. Read more about Anna’s doctoral research here.

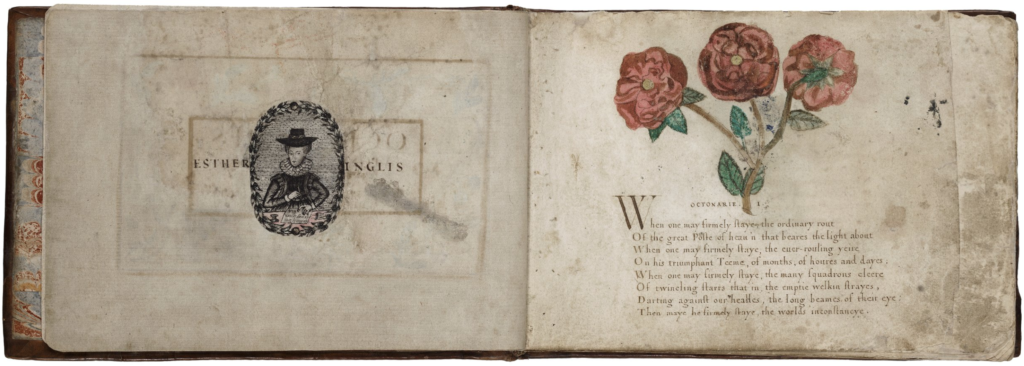

Welcome to the new blog for “Esther Inglis 2024”. This project will run at Edinburgh University Library throughout 2024, to mark 400 years since the death of Esther Inglis (c.1570-1624). Esther Inglis was a remarkable calligrapher, author, artist, and manuscript-maker of the late-sixteenth and early-seventeenth centuries, who for much of her life was based in Edinburgh. The intention of the project is to raise Esther Inglis’ profile, nationally and internationally, bringing her story to new and varied audiences. The project will mark Esther’s quatercentenary by celebrating the life and work of this exceptional woman, and locating her scribal and artistic productions within a broader cultural heritage, in Scotland and beyond. This blog will be a place to record the progress of the project, while also providing space for guest posts, wider discussions, and spotlights on particular elements of Inglis’ work. As Project Curator of “Esther Inglis 2024”, my primary output will be the development of an online exhibition which will tell Inglis’ story, and situate her work within wider cultural and historical contexts. The exhibition will bring together digital manifests of the Inglis’ manuscripts which are currently held in libraries and institutions throughout the world. The hope is for the exhibition to become a lasting scholarly and public resource, through which Esther’s story and her books can be known more widely.

In this first post, it seems fitting to introduce Esther Inglis, with an outline of her life and her manuscripts.

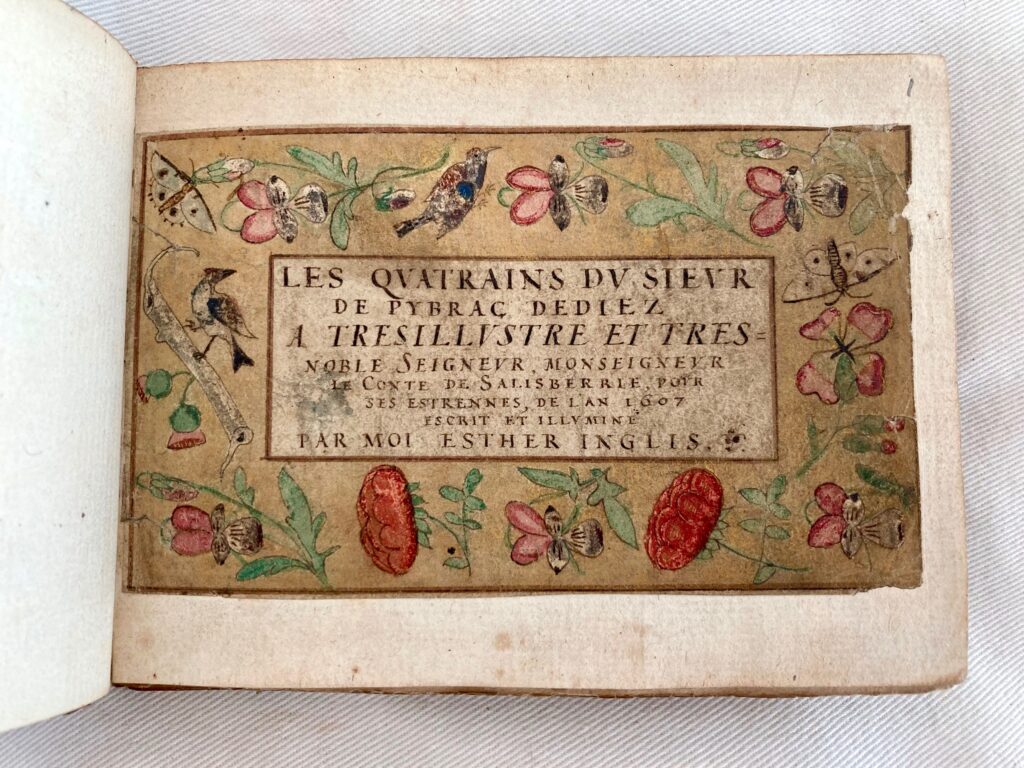

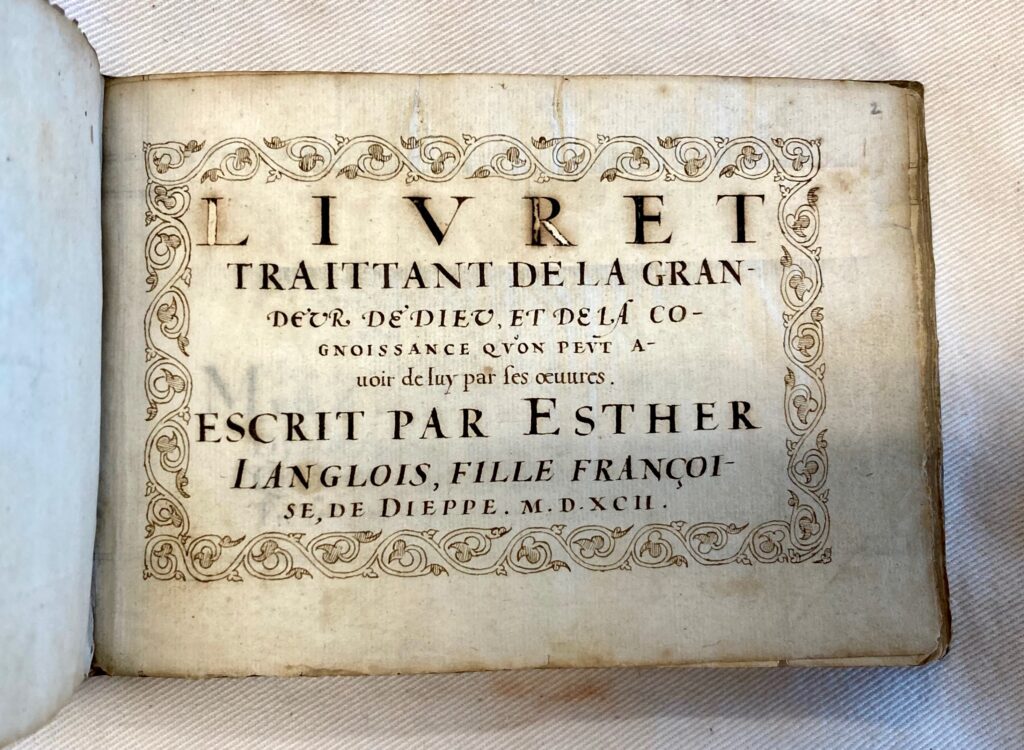

Esther Inglis was the daughter of French Huguenot refugees, Nicolas Langlois and Marie Presot, who emigrated from Dieppe to Britain close to 1570, to escape religious persecution. The family moved first to London, and then settled in Edinburgh, where Nicolas Langlois became master of the French school. Esther Inglis’ first surviving manuscript dates to 1586, when she was around 16 years old, and is a copy of two Psalms written in five different kinds of script. Her ability to work in multiple different forms of writing would come to distinguish her as a scribe. Across Esther’s corpus, her range of scripts includes letters which are reversed, zigzagging, or interlaced, miniature writing, and imitation of print. Marie Presot was a calligrapher, and it is likely that she first taught her daughter how to write. But Esther also learned her forms of writing from several ‘writing-manuals’, a genre of early-modern manuscript or printed books produced as teaching tools. These books provide examples of different handwriting styles, with sample-texts to copy from. Such books were produced throughout Europe in the second half of the sixteenth century, but Esther seems to have used those particularly produced by French writing-masters: Pierre Hamon’s Alphabet de plusieurs sortes de lettres (1567), and A Booke containing diverse sortes of handes (1571) by Jean de Beauchesne, another Huguenot scribe working in London. In total, 65 manuscripts produced by Esther Inglis are known today. For a woman working in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, this is an astonishing quantity of surviving works, and there are likely to be others; many new manuscripts by Esther Inglis have come to light since scholarly interest in her work was revived in the late twentieth century.

Nearly all of Esther Inglis’ manuscripts are bound books, and many of these were produced as gifts, which were presented to their chosen recipients with the probable hope of patronage. The vast majority contain devotional texts — either texts copied from the Geneva Bible, works of paraphrase, or other religious verse. As an author as well as a scribe, Inglis also composed some of the works which she copies into her manuscripts; she was bilingual in French and Anglo-Scots. Close to one-third of Inglis’ corpus is composed of floral, illuminated manuscripts; many of her manuscripts are truly miniature; others imitate different kinds of early-modern printed book with an accuracy that makes it hard to believe these are truly works of the pen. The variety and richness of Inglis’ manuscripts becomes a challenge when seeking to do justice to her corpus, but the hope is for “Esther Inglis 2024” to assist in celebrating the range of her skills and the interweaving of the many different influences which are brought together within the books she makes.

As the project will also emphasise, Esther Inglis was deeply integrated into the social, political, religious, and textual cultures of early-modern Edinburgh. Around 1596, Esther married a Scotsman named Bartilmo or Bartholomew Kello (c.1564-1631), who trained within the Scottish Kirk and who was part of the spy network surrounding Anthony Bacon (1558-1601). Esther Inglis’ involvement not only with the royal court of King James VI, but also with networks of scholars, literary authors, religious reformers, and other scribes working in Edinburgh and its surroundings, will all become central focus-points of the research underpinning this project.

As the project gets underway, an important first step is facilitating the digitisation of the six Esther Inglis manuscripts held in Edinburgh University Library, so that they can be included in the project’s online exhibition. These Inglis manuscripts were all once owned by the Scottish antiquary David Laing, an important early collector of Esther Inglis’ work. In preparation for this digitisation, I have been working on fuller descriptions of these Edinburgh-held manuscripts. A sample of this work can be seen here, while the full range of the Inglis-associated manuscripts held in Edinburgh University Library can be found here. Ahead of their digitisation, several of these manuscripts will require some conservation work, and I hope to share this process on the blog as the work progresses in the next few months.

If you would like to hear more about the research, discoveries, and progress of “Esther Inglis 2024”, make sure to follow its social media channels; the project can currently be found on Instagram and on X. And for the most up-to-date record of Esther Inglis’ known manuscripts, see the listing compiled here by Dr Georgianna Ziegler (Folger Shakespeare Library).

2 thoughts on “Esther Inglis 2024: Project Introduction”