We were saddened to learn recently of the death of the artist and stage designer Yolanda Sonnabend, on 9 November 2015. In May 2013 we were delighted to acquire a collection of 200 or so artworks by Sonnabend, produced in collaboration with the developmental biologist C.H. Waddington, whose papers were catalogued as part of the ‘Towards Dolly’ project. This collection was first viewed in 2010 by our colleague Graeme Eddie, who visited Sonnabend in her home and took the photographs featured here.

We were saddened to learn recently of the death of the artist and stage designer Yolanda Sonnabend, on 9 November 2015. In May 2013 we were delighted to acquire a collection of 200 or so artworks by Sonnabend, produced in collaboration with the developmental biologist C.H. Waddington, whose papers were catalogued as part of the ‘Towards Dolly’ project. This collection was first viewed in 2010 by our colleague Graeme Eddie, who visited Sonnabend in her home and took the photographs featured here.

Yolanda Pauline Tamara Sonnabend was born on 26 March 1935 in Bulawayo, Southern

Yolanda Pauline Tamara Sonnabend was born on 26 March 1935 in Bulawayo, Southern

Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) to German-Russian parents. After a cultured upbringing, Yolanda went on to study art in Geneva, and painting and stage design at the Slade School of Fine Art, London. She received her first design commission at the Royal Ballet in 1958, while she was still an undergraduate, and went on to forge a brilliant career as a stage designer. She worked closely with the choreographer Sir Kenneth MacMillan throughout the 1960s-1980s, and designed for theatre, opera and ballet shows across Europe, as well as designing Derek Jarman’s 1979 film adaptation of The Tempest. She was also an acclaimed portrait painter, whose subjects included Stephen Hawking and Steven Berkoff. In 2000 Sonnabend was awarded the Garrick/Milne Prize for theatrical portraiture.

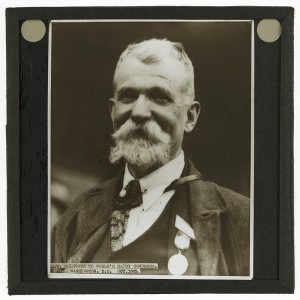

Sonnabend’s friendship and collaboration with C.H. Waddington is captured in the illustrations she produced for his book Tools for Thought: how to understand and apply the latest scientific techniques of problem solving. Waddington was a biologist and embryologist, and at the time he knew Sonnabend, was the director of the Institute of Animal Genetics in Edinburgh. However, Waddington’s interests extended far beyond the purely scientific, encompassing art, architecture, ecology, robotics and early computing; he was also committed to communicating with the wider public about these topics. Tools for Thought was his final book, published posthumously in 1977, and was intended to be a popular guide to new ways of perceiving and understanding the world’s scientific, political and ecological problems. Sonnabend’s stark and imaginative pen and ink drawings formed the perfect ‘other half’ to the book; incorporating triangles, graphs, arrows and bird heads.

Many of Sonnabend’s designs were, sadly, not included in the final book (Waddington died during the proofing stage), but the originals exist in the collection acquired by the Library.  Sketches on graph paper and collages made with shredded magazine articles sit alongside completed, signed pieces. The correspondence which accompanies these works shows the affectionate and intellectual stimulating relationship Sonnabend and Waddington shared.

Sketches on graph paper and collages made with shredded magazine articles sit alongside completed, signed pieces. The correspondence which accompanies these works shows the affectionate and intellectual stimulating relationship Sonnabend and Waddington shared.

Sonnabend’s artistic legacy lives on in the portraits collected by the National Portrait Gallery and the Science Museum and the Design Collection at the Royal Opera House – but her work for C.H. Waddington sheds a new light on both their careers.

With thanks to Graeme Eddie and Dr Joseph Sonnabend.

Clare Button

Project Archivist