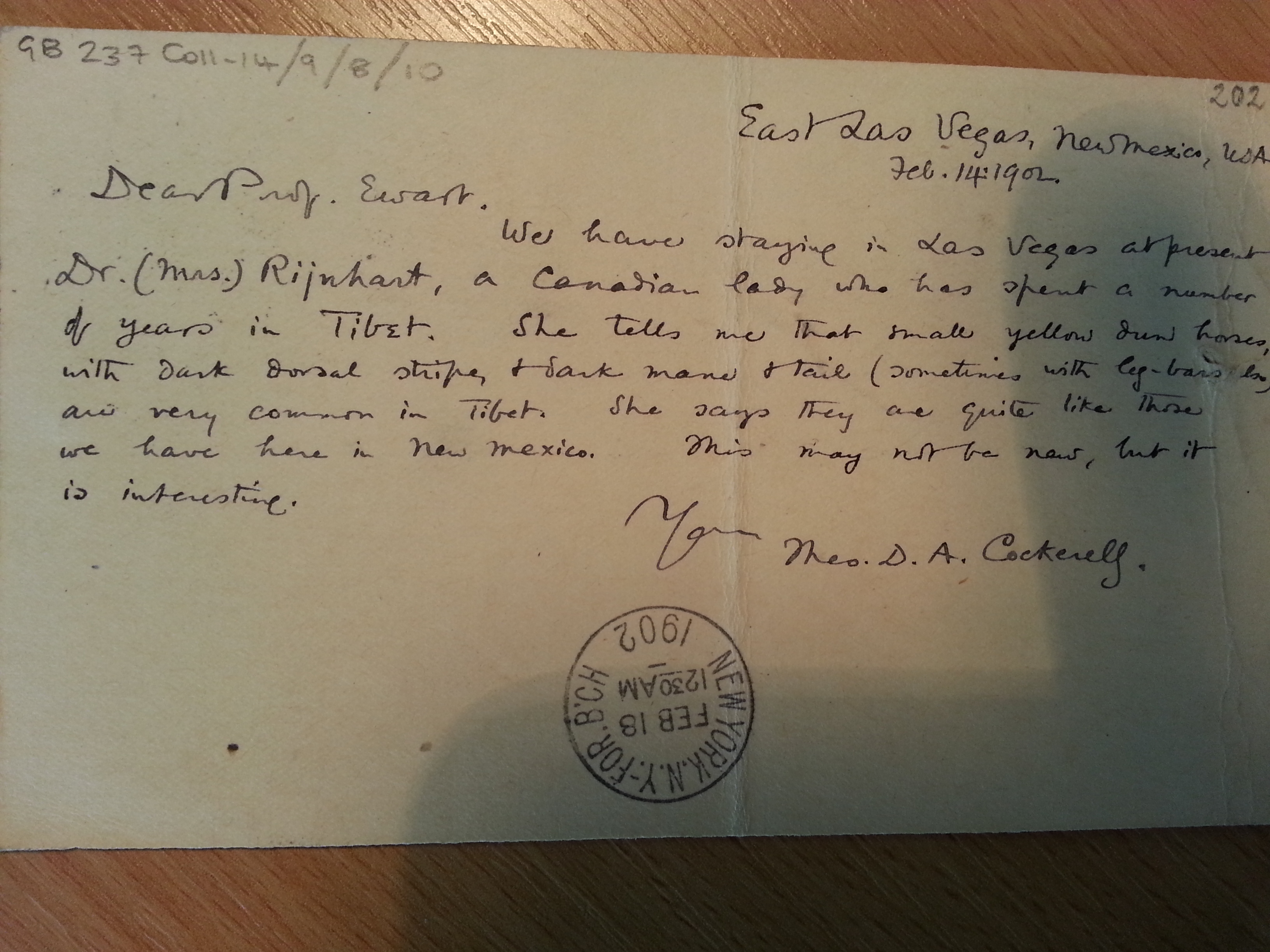

Cataloguing the correspondence of zoologist/animal breeder James Cossar Ewart (1851-1933), I have been intrigued by the various ‘life stories’ which emerge from the letters. Periodically I will be including some highlights in a series of posts entitled ‘letters in the limelight’ .

Cataloguing the correspondence of zoologist/animal breeder James Cossar Ewart (1851-1933), I have been intrigued by the various ‘life stories’ which emerge from the letters. Periodically I will be including some highlights in a series of posts entitled ‘letters in the limelight’ .

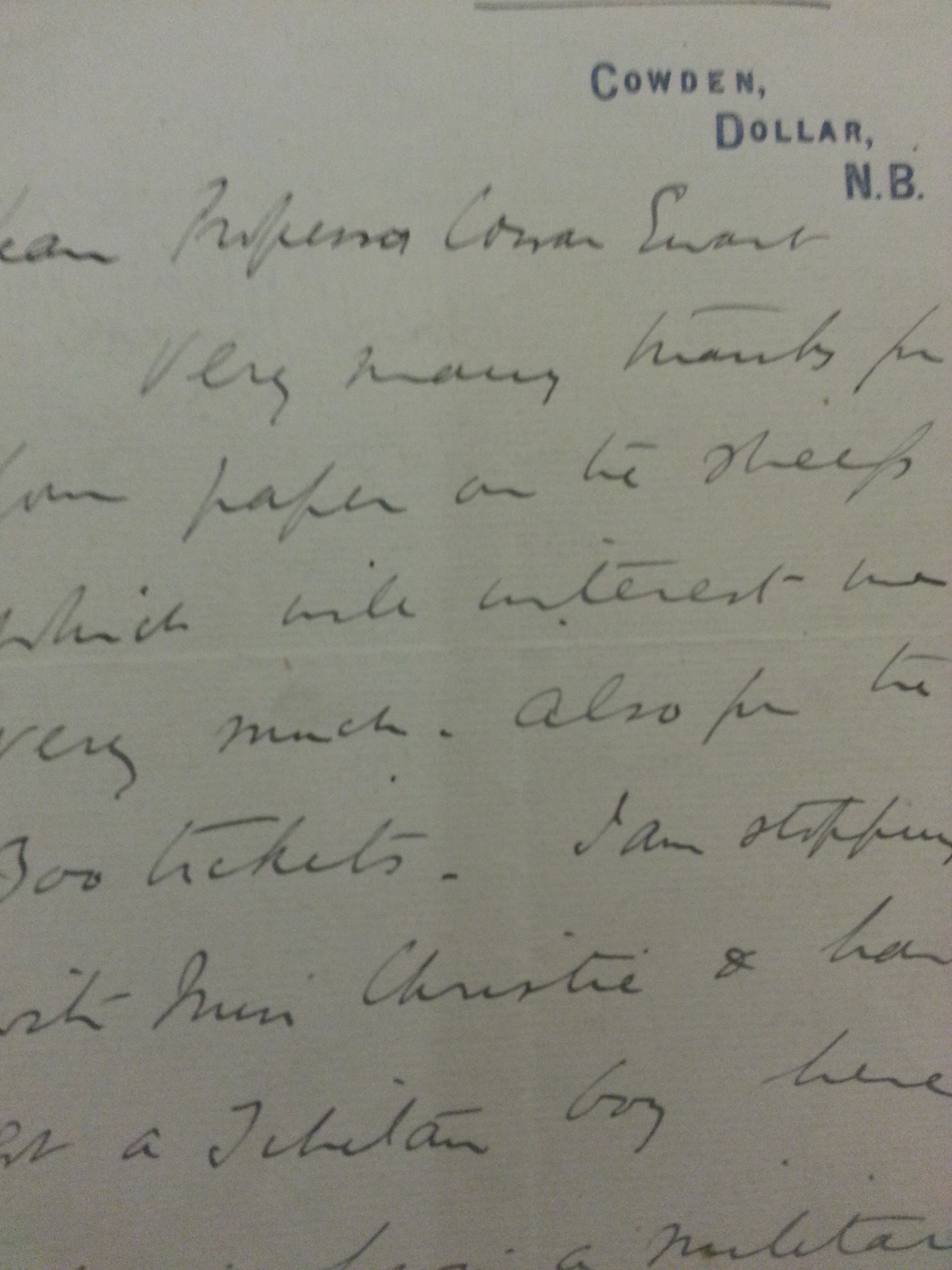

Sometimes even the smallest mention of a name in a letter contains the kernel of a fascinating story. On 13 June 1915, Mr Bailey writes to Ewart that he is currently staying with a ‘Miss Christie’ at Cowden Castle, Dollar, Perthshire, where a ‘Tahitian boy’ is lodging and receiving a military education. Bailey also provides some details about the sheep he has seen in Tahiti, which would have been of relevance to Ewart’s researches into different sheep breeds at this time. But who was this ‘Miss Christie’, Mr Bailey’s host at Cowden Castle?

Isabella (Ella) Robertson Christie (1861-1949) was an independent woman who travelled the world, photographed and wrote about her experiences and was made a Fellow of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society as well as the Royal Geographical Society. However, she is now best remembered for the Japanese garden she commissioned in the grounds of her home at Cowden Castle. When visiting Japan in 1907, Christie was especially struck by the gardens, which she wrote ‘were first copied from the Chinese, and then improved upon the lines of nature till one can scarcely see where the artificial and natural join.’ Once back at Cowden, Christie created a lake out of some marshy ground and employed Japanese designer Taki Hionda, from Nagoya’s Royal School of Garden Design, to help create a garden filled with symbolic stones that traced a route around the lake. The garden, named Shah-rak-uenor (Place of Pleasure and Delight) was frequently used for entertaining the friends and visitors who came to Cowden from all over the world. A favourite activity of visitors would be to take a fishing trip on the lake before tea, served in the tea house on an island in the middle of the lake.

Christie later called upon the advice of Professor Jiju Soya Susuki of the Soami School of Imperial Design, who deemed the gardens ‘the best in the western world’, except for the bridge, which he called ‘a flaw in a precious gem.’ Suzuki insisted on redesigning the bridge. In 1925, Christie used her contact with Susuki to employ a gardener called Matsuo, who had lost his entire family in an earthquake in Japan. Matsuo was able to provide specialist care for the plants and although he had little English and Ella Christie had no Japanese, they were clearly able to find a way to communicate. Christie granted Matsuo an estate cottage, and when he died in 1937 he was buried next to the Christie family plot in the cemetery of Muckhart Church.

After Ella Christie’s death in 1947, the Japanese gardens were maintained and kept open to the public, even after Cowden Castle was demolished in 1952. However, things quickly deteriorated. Several acts of vandalism in the 1960s, including the burning of the teahouse, the destruction of the bridges, shrine and lanterns, left Ella Christie’s beloved garden in ruins. Now, despite efforts to raise money to restore the gardens, not to mention the enthusiasm of Christie’s great-nephew and the current owner of the estate, Sir Robert Stewart of Arndean, little remains of Sharakuen except the lake, some stonework and a few tantalising fragments of the shrine, although the rhododendrons that Christie imported from the Himalayas can still be seen.

Although it would be nice to know more about the ‘Tahitian boy’ undergoing military training that F. Bailey mentions, his letter’s brief hint does at least point the way towards the fascinating life of Ella Christie and the garden she created.

You can read more information about the Ella Christie’s Japanese garden, and also see some pictures, here: http://www.geocities.jp/kita36362000/perthshire_english.htm

Photographs from Ella Christie’s travels can be seen on the Royal Geographical Society’s website: http://www.rsgs.org/ifa/gemellachristie.html

I am also indebted to Catherine Horwood’s book, Gardening Women: Their Stories from 1600 to the Present (Virago, 2010).