The Roslin Collection comprises a surprisingly wide-range of material from archival papers, the bound collection of scientific offprints and glass slides. It also includes 71 books on agriculture, animal breeding and genetics. The span of topics and time is remarkable – the earliest book in the collection is a book on Italian horse breeding from 1573  up to a book on Scottish photography from 1999! These books were used by scientists at the Institute of Animal Genetics Library, Edinburgh; Animal Breeding Research Organization and Animal Breeding Research Department, University of Edinburgh; University of Edinburgh Agricultural Department, Poultry Research Centre, the Commonwealth Breeding Organization, Imperial Bureau of Animal Breeding and Genetics and Roslin including Professor Robert Wallace and FAE Crew. Some books contain beautiful fold-out illustrations and may have some annotations.

up to a book on Scottish photography from 1999! These books were used by scientists at the Institute of Animal Genetics Library, Edinburgh; Animal Breeding Research Organization and Animal Breeding Research Department, University of Edinburgh; University of Edinburgh Agricultural Department, Poultry Research Centre, the Commonwealth Breeding Organization, Imperial Bureau of Animal Breeding and Genetics and Roslin including Professor Robert Wallace and FAE Crew. Some books contain beautiful fold-out illustrations and may have some annotations.

To give you an idea of the scope of the collection:

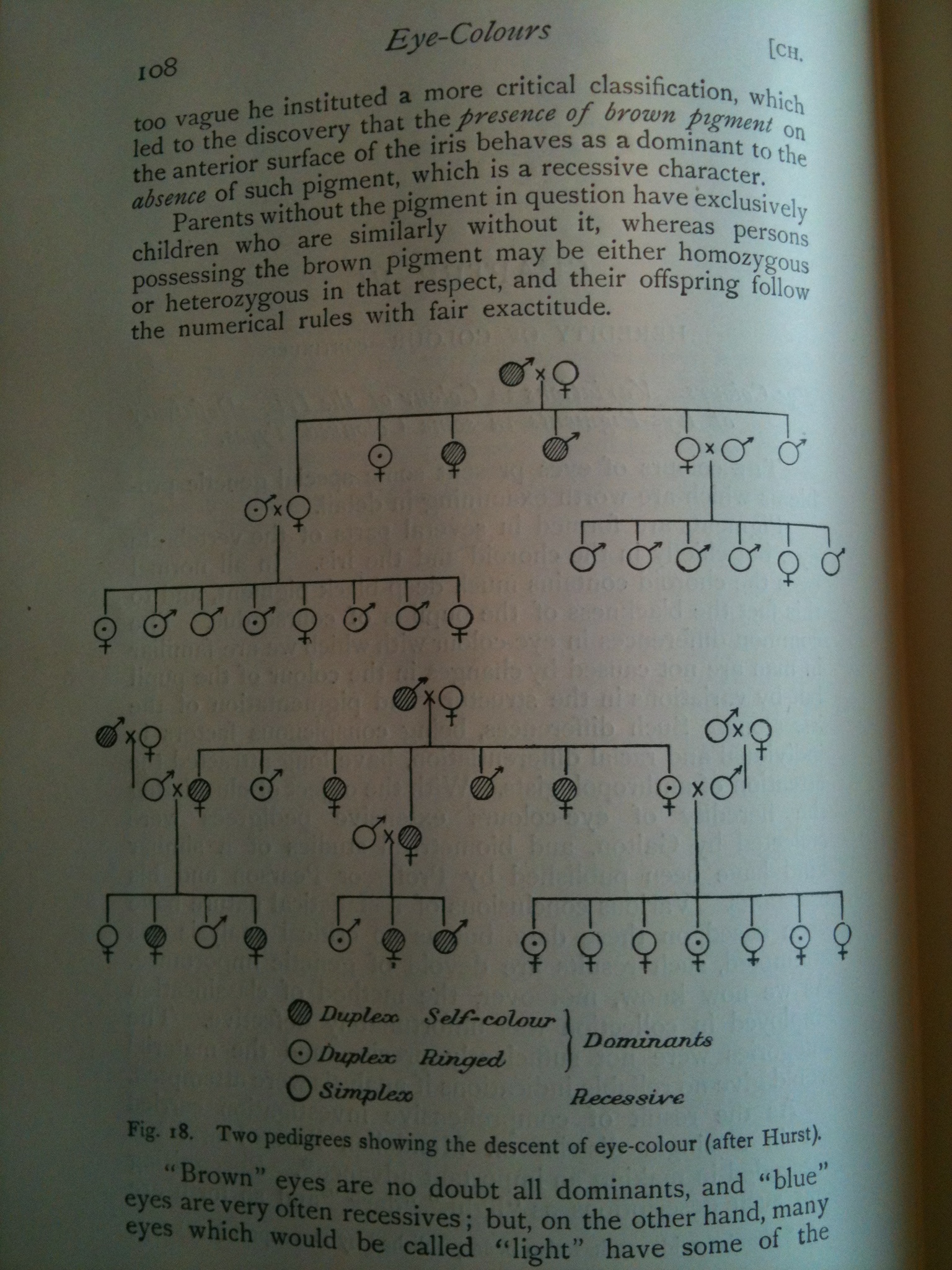

Corte, Claudio, Il Cauallerizzo de Claudio Corte da Pauia, 1573; Instruction sur la maniere d’elever et de perfectionner la bonne espece des betes a laine de Flandre, 1763; Buc’hoz, Traité Economique et physique des oiseaux de basse-cour, 1775; Hunter, A., Georgical Essays, 1777; Bakewell and Culley, Letters from Robert Bakewell to George Culley, 1777; Great Britain Board of Agriculture, Communications to the Board of Agriculture, vol. 1-7,1797-1813; Salle-Pigny, F.A., Essai sur l’education et l’amelioration des betes a laine…, 1811; Desaive, Maximillian, Les Animaux Domestiques, 1842; Low, David, The Breeds of the Domestic Animals of the British Islands Vol. 1 & 2, 1842; Dickson, Walter B., Poultry: their breeding, rearing, diseases, and general management, 1847; Dixon, Reverend Edmund Saul, Ornamental and Domestic Poultry, 1848; Dickson, James, The Breeding and Economy of Livestock…, 1851; Youatt, William, The Dog, 1852; Doyle, Martin (ed), The Illustrated Book of Domestic Poultry, 1854; Wegener, J.F. Wilhelm, Das Hühner- Buch, 1861; Brown, D J, The American Poultry Yard, 1863; Charnace, Le Cte Guy de, Etudes sur les animaux domestiques, 1864; Youatt, William, Sheep, 1869; Bates, Thomas, The History of Improved Short-Horn or Durham cattle …, 1871; Nathusius, Hermann, Vortrage über Viehsucht,1872; Coleman, J, The Cattle of Great Britain: being a series of articles on the various breeds…vol.1 & 2, 1875; La Pere de Roo, Monagraphie des Poules, 1882; Tegetemeir, WB, Pigeons: their structure, varieties, habits, and management, 1883; Poli, A and G Magri, Il bestiame bovino in Italia, 1884; McMurtrie, William, Report upon an examination of Wools and other Animal Fibres, 1886; Croad, AC, The Langshan Fowl, it’s history and characteristics, 1889; Wright, L, The Practical Poultry Keeper, 1890; Tegetmeier, WB, Poultry for the Table and Market…, 1893; Gordon, DJ, The Murray Merino, 1895-96; Theobald, Fred V., The Parasitic Diseases of Poultry, 1896; Felch, IK, Poultry Culture. How to Raise, Manage, Mage and Judge, 1898; Hearnshaw, Roger R, The Rosecomb Bantam, 1901; Weir, Harrison, Our Poultry and All About Them, Vol. 1 & 2, 1902; Parlin, S W, The American Trotter, 1905; Axe, Professor J Wortley, The Horse: its treatment in health and disease, Vol. 1-9, 1905; Davenport, CB, Inheritance in Poultry, 1906; Gunn, WD, Cattle of Southern India, 1909; Committee of Inquiry on Grouse Disease, The grouse in health and in disease Vol. 1 & 2, 1911; Hewlett, K, Breeds of Indian Cattle, Bombay Presidency, 1912; Lewis, Harry R, Productive Poultry Husbandry, 1913; Bateson, W, Mendel’s Principles of Heredity, 1930; Punnett, RC, Notes on Old Poultry Books, 1930; Houlton, Charles, Cage-bird hybrids : containing full directions for the selection, breeding, exhibition and general management of canary mules and British bird hybrids, 1930; Prentice, E Parmale, The History of Channel Island Cattle: Gurnseys and Jerseys, 1930; Hays, FA and Klein, GT, Poultry Breeding Applied, 1943; Odlum, George M, An Analysis of the Manningford Herd of British Friesians, 1945; Heiman, Victor (editor), Kasco Poultry Guide, 1950; Schlyger, Hühnerrassesn, c1951; Hartley and Hook, Optical Chick Sexing, 1954; Tyler, Cyril, Wilhelm von Nathusius 1821-1899 on Avian Eggshells, 1964; Marsden, Aloysius, The effects of environmental temperature on energy intake and egg production in the fowl, 1981; Ford, Donald, Millennium Images of Scotland, 1999; Bayon, HP, Diseases of Poultry: their prevention and treatment, n.d.

This collection of books provide a valuable resource for the collection as it offers an insight into what the scientists were reading and researching over the years. Over then next few weeks I’ll be highlighting some of the gems of the collection!