Our intern, Nathalie, is reaching the end of the project, working on the earliest of the library records. She has achieved a great deal in the weeks she has been with us: we have a set of descriptions of the documents ready to transfer into the Archives cataloguing software, and the draft of a research guide to the early records ready to go onto the CRC web page. These have already helped us answer enquiries about the early library collections. We presented a short paper about the project and the records at the recent conference of the CILIP Library and Information History Group conference in Dundee.

Nathalie reflects on the project and what she has learnt. We wish her well as she goes back to her studies for the new academic year, and hope we have given her the bug for old library records!

The Early Library Records Project began as a project aimed at opening up a series of early records to make them easier to navigate. With just under 55 items to examine in 10 weeks, the project had clear objectives: the flagging up of items needing conservation work, or to prioritise for digitisation, the update of the information available on the online catalogue for early library records and the creation of a research guide to enable researchers, members of the public and CRC staff to understand early library records better. It is hoped that the results of the project will have far-reaching benefits. To enhance the data on the online catalogue, the type of information gathered from the records needed to be consistent, despite their being very varied in kind. The focus has thus been on: their approximate period of use, their purpose, their potential compilers and users and the language they are written in.

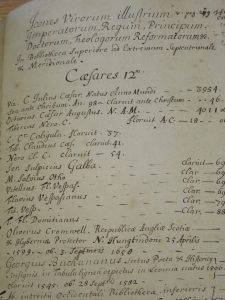

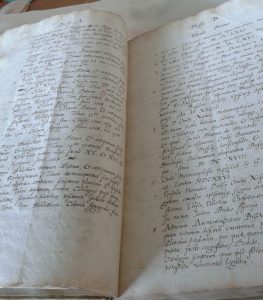

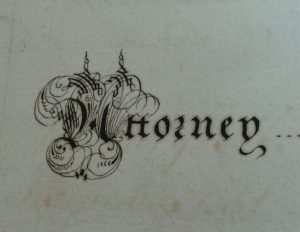

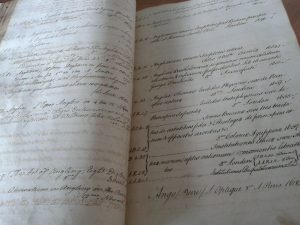

The diversity of these records is worth mentioning. The library possesses early press and author catalogues, account books, matriculation registers, borrowing registers, accessions books and subject catalogues. Some periods in the library’s history are richer in certain types of records, but overall, there is some record to be found for every half century up to now. These records not only give us precious general information about the management of the library, but also give us information about the university at large. They also contain numerous precious details which are at times surprising, comical, confusing or enlightening.

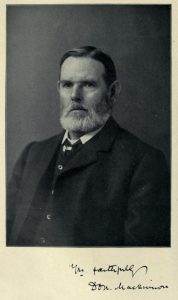

The project had its share of surprises. Scientific instruments such as telescopes, microscopes, globes and quadrants appeared from time to time, either in a list of instructions on how to use them, or in an account book when money had been spent to mend or purchase them. Equally, I met with volumes which had unexpected contents. Da.1.5 is such an item, as it is a collation of three different inventories: a manuscript author catalogue, followed by a printed version of the Nairn catalogue, itself followed by a manuscript list of pamphlets and other titles belonging to the library of the College of Surgeons. I was glad to come across a few references in Gaelic, such as the Gaelic translation of Dodsley’s work The Economy of Human Life and a few other entries, all in the 4-volume author catalogue compiled in the 1750s. Some of the earliest volumes exhibited physical conventions of early book production such as catchwords and folio numbers, while item Da.1.15 is a fantastic illustration of stationary binding, only used for certain types of records, especially ledgers. While working on the project, I became acquainted with several librarians through their observations, especially the Hendersons. Together, the father and his son were librarians to the university library for 80 years (1667-1747). Both left numerous notes in the catalogues and account books, and their comments, sometimes stern, allow us to get a glimpse into the day-to-day management of the library.

What is more, the outcome of the project goes further than suggested above. As a range of sources is now better known, new routes for future enquiry have emerged. As we know more about what kind of information can be had in these records, we can be bolder in our research questions. Interesting research could be done on the borrowing registers still surviving, and a study of the donations to the library could also be valuable. Beside these potential routes for future research, the project’s results have also challenged some previously-held beliefs. For example, it has been discovered that what was thought to be a 1636 author catalogue is in fact more likely to be a late 17th century author catalogue.

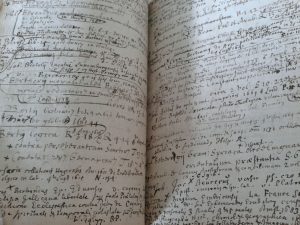

There have been challenges, for sure. Deciphering 17th century script was not always easy for me, as I did not have any previous experience in palaeography. Formatting the data I was compiling so that it would be easily transferable to Archives Space was also something I had to get my head round. Equally, I had to acquire some elementary knowledge about the university’s early history, its buildings and running, since these elements impacted on the library’s administration and evolution. Yet, these challenges have only had valuable outcomes, most likely because I was working in a particularly supportive environment.

Beside the benefits of the project’s results for CRC staff, researchers and members of the public, a significant outcome of the project is what it has brought to me, as an intern. I have not only learnt a great deal about the library’s management and history in the pre-Enlightenment and Enlightenment periods, but also gained experience in working with archival material. I have absorbed the basics of cataloguing, found out about digitisation projects, shadowed several people’s work and all this has given me an acute sense of what the CRC is about. This internship was a truly unique opportunity which has given me insight into the library and museum professional sector.

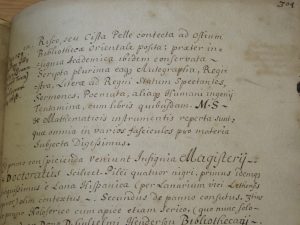

The library has, from very early on, been a welcoming home to objects other than books. This can be seen in items Da.1.18 and 19, as both contain several lists of wonders and curiosities. We are indeed told that precious items were kept in a chest – a sort of 17th century equivalent to our fire-safe! Among the items precious enough to go in the chest were the Bohemian Protest, the marriage contract between Mary Queen of Scots and Francis Dauphin of France, and a thistle banner printed on satin 1640 being found carelessly put in one of Mr Nairn’s books. What is more, a list is given us of portraits that were hung in the library, a celebration of illustrious men and women. Featured celebrities included Tiberius Claudius, Martin Luther, and Mary Queen of Scots. We still do hold some of these portraits. Items related to the discipline of anatomy were also gifted to the library, and we are told in several lists that these comprised the ‘skeleton of a French man’, or a ‘gravel stone (…) cut out of the bladder of Colonel Ruthven’, who, we are informed in Da.1.31, ‘lived six weeks thereafter’.

The library has, from very early on, been a welcoming home to objects other than books. This can be seen in items Da.1.18 and 19, as both contain several lists of wonders and curiosities. We are indeed told that precious items were kept in a chest – a sort of 17th century equivalent to our fire-safe! Among the items precious enough to go in the chest were the Bohemian Protest, the marriage contract between Mary Queen of Scots and Francis Dauphin of France, and a thistle banner printed on satin 1640 being found carelessly put in one of Mr Nairn’s books. What is more, a list is given us of portraits that were hung in the library, a celebration of illustrious men and women. Featured celebrities included Tiberius Claudius, Martin Luther, and Mary Queen of Scots. We still do hold some of these portraits. Items related to the discipline of anatomy were also gifted to the library, and we are told in several lists that these comprised the ‘skeleton of a French man’, or a ‘gravel stone (…) cut out of the bladder of Colonel Ruthven’, who, we are informed in Da.1.31, ‘lived six weeks thereafter’.