Home University of Edinburgh Library Essentials

February 24, 2026

New to the Library: Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome

I’m happy to let you know that the Library now has access to the Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome from Oxford Reference Online. This encyclopedia offers a comprehensive overview of the major cultures of the classical Mediterranean world—Greek, Hellenistic, and Roman—from the Bronze Age to the fifth century CE.

You can access the Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome via DiscoverEd.

The encyclopedia brings the work of the best classical scholars, archaeologists, and historians together in an easy-to-use format. With over 1000 articles written by leading scholars in the field, it seeks to convey the significance of the people, places, and historical events of classical antiquity, together with its intellectual and material culture. Broad overviews of literature, history, archaeology, art, philosophy, science, and religion are complimented by articles on authors and their works, literary genres and periods, historical figures and events, archaeologists and archaeological sites, artists and artistic themes and materials, philosophers and philosophical schools, scientists and scientific areas, gods, heroes, and myths. Read More

The encyclopedia brings the work of the best classical scholars, archaeologists, and historians together in an easy-to-use format. With over 1000 articles written by leading scholars in the field, it seeks to convey the significance of the people, places, and historical events of classical antiquity, together with its intellectual and material culture. Broad overviews of literature, history, archaeology, art, philosophy, science, and religion are complimented by articles on authors and their works, literary genres and periods, historical figures and events, archaeologists and archaeological sites, artists and artistic themes and materials, philosophers and philosophical schools, scientists and scientific areas, gods, heroes, and myths. Read More

The Aberdeen Breviary: A National Treasure

The Aberdeen Breviary is a highly significant book for a number of reasons. Initiated by King James IV and compiled by Bishop William Elphinstone, it is Scotland’s first printed book, published in Edinburgh in 1510. It also represents the most in depth collection of information on the lives and stories of Scottish Saints. Our copy is one of five known remaining original copies making it a key addition to our Iconics Collection. Read More

New to the Library: Illustrated London News Historical Archive

I’m delighted to let you know that the Library now has access to The Illustrated London News Historical Archive, 1842-2003 from Gale Cengage. Illustrated London News was the world’s first pictorial weekly newspaper and this archive gives access to the full run of this iconic illustrated newspaper.

You can access The Illustrated London News Historical Archive via the Databases A-Z list and the Newspapers & Magazine databases list.

The first issue of Illustrated London News was published on Saturday 14 May 1842 and as the world’s first fully illustrated weekly newspaper, it marked a revolution in journalism and news reporting.

Screenshot from front page of Illustrated London News, May 14, 1842; pg. [1]; Issue 1.

New to the Library: Foreign Office Files for China, 1919-1937

I’m really pleased to let you know that the Library has recently purchased access to the Foreign Office Files for China, 1919-1937 from Adam Matthew Digital. This means we now have access to the full Foreign Office Files for China database covering the years 1919 to 1980. This fantastic resource provides access to the digitised archive of British Foreign Office files dealing with China, Hong Kong and Taiwan.

You can access Foreign Office Files for China, 1919-1980 via the Databases A-Z list, Primary source database list, the History Subject Guide or DiscoverEd. Read More

My Royal Mile

This week, we have our final blog from Project Conservator, Helen Baguley, who has been working with us for the past 18 months on the Collections Rationalisation Project…

The Royal Mile is an iconic street which runs through the centre of Edinburgh. It is a ‘must see’ attraction for tourists, and one of the first places I visited when I moved up to Edinburgh for my new job which began 18 months ago. Running from the Castle to Holyrood, the Royal Mile is actually slightly longer than a mile, and measures 1.81 kilometres. Here at the Centre for Research Collections (CRC), I have been working within the conservation department on the Collections Rationalisation Project, caring for some of the rare books and archive collections which are housed at the University Collections Facility (UCF) and the Main Library. As my contract here has now come to an end, I have added up the linear meterage of the shelves which house the collection I have been working on, and it comes to an incredible 1801.25 metres. To put this into perspective, 1801.25 metres is just 8.75 metres short of the Royal Mile. But I think my Royal Mile is just as historic and exciting, as it is made up of beautiful rare books, interesting archives and fascinating objects from the collections!

Steps Through Time at New College Library

Have you seen the new Steps Through Time display at New College Library? Today we’re celebrating the Steps Through Time project, which developed six display panels to be mounted alongside the steps up into New College Library. These panels highlight treasures from New College Library’s rare book and archive collections against a timeline of Scottish and religious history.

Student engagement event

This project kicked off with a student engagement event between Monday 23 to Wednesday 25 April. We held a daily display of New College Special Collections items featuring items from two different centuries each day, and encouraged students to take a few minutes break from their revision to vote on their favourite items from each century. Over the three days we had nearly 120 visitors to our displays, many of whom commented that they had no idea that New College Library held Special Collections items like these. I’m grateful to my two volunteers, Nastassja Alfonso and Jessica Wilkinson, for helping with these events and persuading revising students that they really did want to look at some Special Collections. The item that gathered the most votes was the 1638 National Covenant (bequeathed by Thomas Guthrie), which is one of five National Covenants in the New College Library collections. The National Covenants have recently returned to New College Library after benefiting from conservation work and digital photography at the CRC.

Image selection and text writing

A key task was the selection of the images, which we did with the data gathered from students votes, but also by consulting with student representatives from the School of Divinity. A clear message about representing diversity in our text and image choices was received from the student community and so we aimed to curate diversity into the timeline narrative. Student engagement transformed the project into more than developing some display panels of library treasures. If we had planned just to do that, the panels would have included images of incunabula, Bibles or Luther pamphlets, some of New College’s collection strengths. But that was not the story that the student community wanted to tell.

Impact

We hope the project will improve an area of the library entrance which is used by all visitors to the library, and that it will raise the profile of New College Library’s unique Special Collections. We will be gathering feedback both over the summer and in the first few weeks of semester to better understand the impact of the Steps Through Time display.

Christine Love-Rodgers, Academic Support Librarian, Divinity

New! Oxford Handbooks Political Science 2017 collection

I’m pleased to let you know that following a request from staff in Politics & International Relations the Library now has access to the Oxford Handbooks Online Political Science 2017 collection. This includes titles such as The Oxford Handbook of Populism, The Oxford Handbook of Gender and Conflict and The Oxford Handbook of U.S. National Security.

You can access the individual book titles in the collection via DiscoverEd. Or you can access the Oxford Handbooks Online site via the E-books pages. Read More

Marking up collections sites with Schema.org – Blog 2

This blog was written by Nandini Tyagi, who was working with Holly Coulson on this project.

This blog follows the blog post written by Holly Coulson, my fellow intern at the Library Metadata internship with the Digital Development team at Argyle House. For the benefit of those who are directly reading the second blog, I’ll quickly recap what the project was about. The Library Digital Development team have built a number of data‐driven websites to surface the collections content over the past four years; the sites cover a range of disciplines, from Art to Collections Level Descriptions, Musical Instruments to Online Exhibitions. While they work with metadata standards (Spectrum and Dublin Core), and accepted retrieval frameworks (SOLR indices), they are not particularly rich in a semantic sense, and they do not benefit from advances in browser ‘awareness’; specifically, they do not use linked data. The goal of the project was to embed schema.org metadata within the online records of items within Library and University Collections to bring an aspect of linked data into the site’s functionality, and resultantly, increase the sites’ discoverability through generic search engines (Google etc.) and, more locally, the University’s own website search (Funnelback).

In this blog, I’ll share my experience from the implementation perspective i.e. how were the documented mappings translated into action and what are the key findings from this project. Before I dive into implementation of Schema, it is important to know what Schema is and how does it benefit us. Schema.org is a collaborative, community activity with a mission to create, maintain, and promote schemas for structured data on the Internet, on web pages, in email messages, and beyond. Schema.org vocabulary can be used with many different encodings, including RDFa, Microdata and JSON-LD. These vocabularies cover entities, relationships between entities and actions, and can easily be extended through a well-documented extension model. I’ll explain the need for Schema better through an example. Most webmasters are familiar with HTML tags on their pages. Usually, HTML tags tell the browser how to display the information included in the tag. For example, <h1>Titanic</h1> tells the browser to display the text string “Titanic” in a heading 1 format. However, the HTML tag doesn’t give any information about what that text string means—” Titanic” could refer to the hugely successful movie, or it could refer to the name of a ship—and this can make it more difficult for search engines to intelligently display relevant content to a user. In the collections for example, when the search engine would be crawling the pages, they will not understand if a certain title refers to a painting, sculpture or an instrument. Using Schema, we can help the search engine make sense of the information on the webpage and it can list our website at a higher rank for the relevant queries.

Before: No sense of linked data. Search engines would read the title and never understand that these pages refer to items that are a part of creative work collections.

Anatomical Figure of a Horse (ecorche), part of Torrie Collection (before)

Keeping this in mind we started mapping the schema specification in the record files of the website. There were certain fields such as ‘Inscriptions’ and ‘Provenance’ that could not be mapped because Schema does not support a specification for them yet. We are documenting all such findings and plan to make suggestions to Schema.org regarding the same.

Implementation of mapping in the configuration file of Art collections

This was followed by implementing changes directly in the record files of the collection. There were a lot of challenges such as marking up images, videos and audios. Especially from images point of view, some websites used the IIIF format and others used the bitstream which required making wise decisions in how to mark up such websites. With a lot of help and guidance from Scott we were able to resolve these issues and the end result of the efforts was absolutely rewarding.

After: Using the CreativeWorks class of Schema the websites have been marked up. Now, search engines can see that these items refer to creative work category such as art, sculpture, instrument etc. They are rich in other details such as name of creator, name of collection, description etc. These huge changes are bound to increase the discoverability of collections website.

Anatomical Figure of a Horse (ecorche), part of Torrie Collection (after)

I was very fortunate that Google Analytics and Search Engine Optimisation (SEO) trainings were held at the Argyle House during my internship period and I was able to get insights from these trainings. They illuminated a whole new direction and lend a different viewpoint. The SEO workshops in particular gave ideas about optimizing the overall content of the websites and making St.Cecilias more discoverable. I realized the benefits of SEO are seen in the form of increased traffic, Return on Investment (ROI), cost effectiveness, increased site usability and brand awareness. These tools combined with schema can add significant value to the library services everywhere. It is a feeling of immense pride that our university is among the very few universities that have employed schema for their collections. We are confident that schema will make the collections more accessible not only to students but also to the people worldwide who want to discover the jewels held in these collections. The 13 collections website that we worked on during our internship are nearing completion from implementation perspective and will be live soon with Schema markup.

To conclude, my internship has been an amazing experience, both in terms of meaningful strides in the direction of marking up the collections website and the fun, conducive work-culture. Having never worked on the web development side before, I got the opportunity to understand first-hand the intricacies associated in anticipating the needs of users and delivering a perfect information-rich website experience to the users. As the project culminates in July, I am happy to have learned and contributed much more than I imagined I would in the course of my internship.

Nandini Tyagi (Library Digital Development)

Thanks very much to both Nandini and Holly on their sterling work on this project. We’ve implemented schema in 3 sites already (look at https://collections.ed.ac.uk/art for an example), and we have another 6 in github ready to be released. The interns covered a wealth of data, and we think we’re in a position to advise 1) LTW that this material can now be better used in the University website’s search and 2) prospective developers on how to apply this concept to their sites.

Scott Renton (Library Digital Development)

Re-discovering a forgotten songwriter: the archive of Louisa Matilda Crawford

Re-discovering a forgotten songwriter: the archive of Louisa Matilda Crawford.

Daisy Stafford, CRC intern who catalogued the papers of Louisa Matilda Crawford, talks about her experience.

This summer I was offered the opportunity to undertake an archiving internship in the Centre for Research Collections, cataloguing the personal papers of Louisa Matilda Crawford, a nineteenth century songwriter. Other than her name and occupation, little information about Louisa was known. Through two months of close examination of her archive, I was able to stitch together a narrative of Louisa’s life. Here’s what I found…

Louisa Matilda Jane Crawford was born on the 27th September 1789 at Lackham House in Wiltshire. She was the daughter of Ann Courtenay (d. 1816) and George Montagu (1753-1815), an English army officer and naturalist. Louisa was related to nobility on both sides of the family; her maternal grandmother, Lady Jane Stuart, was the sister of Scottish nobleman John Stuart, 3rd Earl of Bute and Prime Minister to George III. Her father, meanwhile, was a descendent of Sir Henry Montagu, the first Earl of Manchester and also the great-grandson of Sir Charles Hedges, Queen Anne’s Secretary.

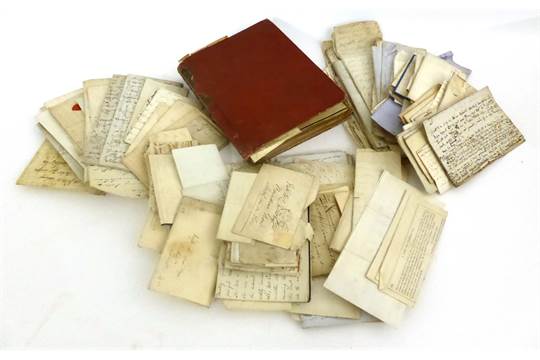

Papers of Louisa Matilda Crawford. Coll-1839 (picture from the seller’s catalogue)

Louisa had three older siblings; George Conway Courtenay (b. 1776), Eleanora Anne (b. 1780) and Frederick Augustus (b. 1783). Little direct information is known about Louisa’s childhood, but it must have been turbulent; in 1798 Montagu left his wife and family and moved to Kingsbridge in Devon to live with his mistress Elizabeth Dorville, with whom he had four more children. It is here that he wrote his two pioneering works, the Ornithological Dictionary; or Alphabetical Synopsis of Birds (1802) and Testacea Britannica, a History of British Marine, Land and Freshwater Shells, which saw several bird and marine species named after him, most notably Montagu’s harrier. The family’s disapproval of his relationship with Dorville ultimately cost him his ancestral home. On the death of his unmarried brother, James, the will stipulated that he would not inherit Lackham House, but had only “a rent charge of £800 a year subject to which the estates were left to his eldest son, George, for life.” The ensuing lawsuit between the pair resulted in huge debts which cost the family the estate; as Louisa wrote in The Metropolitan Magazine in 1835; “The thoughtless extravagance of youth, and the unwise conduct of mature age, caused the estates to be thrown into chancery” (vol. 14, pp. 308-309). Louisa reflected on seeing the native woods of her family home cut down upon its sale in a later poem (Coll-1839/7 pp.415-416):

Those brave old woods, when I saw them fall,

Where they stood in their pride so long,

The giant guards of our ancient hall,

And the theme of our household song;

I wept, that one of my Father’s race

Could forget the name he bore,

And turn the land to a desert place,

Where an Eden bloom’d before.

Louisa began courting Matthew Crawford, a barrister of Middle Temple, in 1817. Many of the papers consist of love letters and poems exchanged between the pair during this early period of their relationship, including three locks of hair, presumably Louisa’s. In 1822 the couple were married and Louisa moved to London, although their continued correspondence evidences that Matthew spent much of their marriage away working in the North of the country. It is then that Louisa began to earn an income through song writing and poetry, although the couple always struggled financially and frequently appealed to their wealthier relatives for aid.

Much of Louisa’s work appeared, often anonymously, in magazines and journals, was sold to publishers, and was set to music by composers Samuel Wesley, Sidney Nelson, Edward Clare and others. She frequently contributed both poems and prose, including several “autobiographical sketches”, to London literary journal The Metropolitan Magazine (which has subsequently been digitised by the HathiTrust and can be fully searched here). Many of her songs and poems related to historical events and persons; songs titled “Anne Boleyn’s Lamentation” (Coll-1839/7 p. 285) or “Chatelar to Mary Queen of Scots” (Coll-1839/7 pp. 381-382) are written from the point of view of famous queens. One poem (Coll-1839/3/1/9) tells the story of Frederick the Great (1712-1786), King of Prussia, who, in order to deceive his enemies as to his position during the Seven Years’ War, commanded that no light should be kindled throughout his encampment. However, a young soldier lit a taper to write a letter to his new bride. The second stanza reads:

His head was bent in act to write,

The memories gusting o’er him –

When through the gloom of gathering night,

Stood Frederick’s self before him!

Oh sternly spoke the Monarch then

His doom of bitter sorrow

“Resume the seat – Resume the pen

And add “I die tomorrow.”

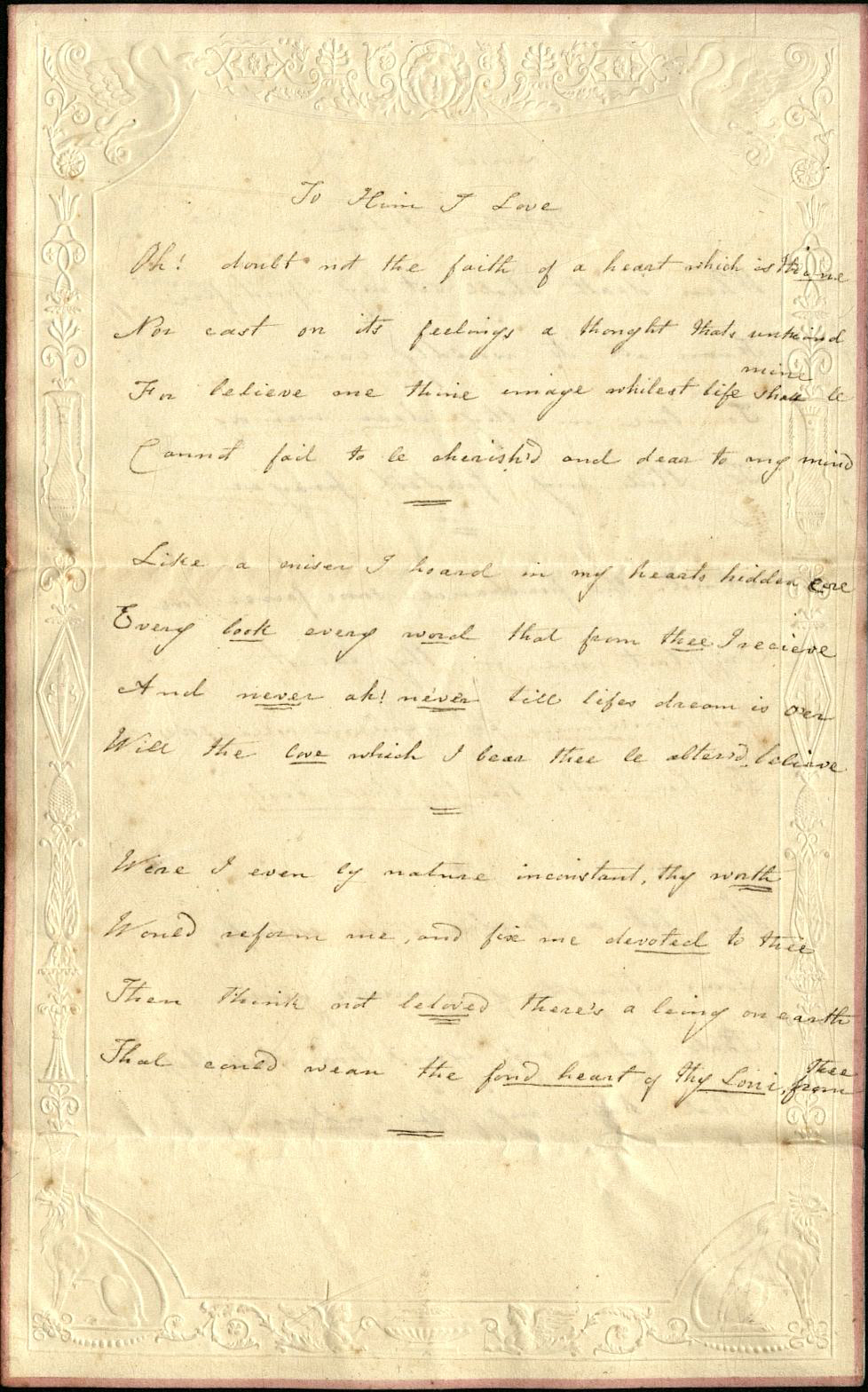

Other poems in the collection are more personal, including reflections on her childhood and family, such as “The Home of Our Childhood” (Coll-1839/7 pp. 17-18) and “On the Death of a Sister” (Coll-1839/7 p. 394). Many verses are addressed to her husband Matthew; one poem (Coll-1839/1/2/5) dated 23rd July 1817 and titled “To Him I Love”, begins:

Oh! Doubt not the faith of a heart which is thine

Nor cast on its feelings a thought thats unkind

For believe me thine image whilest life shall be mine

Cannot fail to be cherish’d and dear to my mind

Like a miser I hoard in my hearts hidden core

Every look every word that from thee I receive

And never ah! never till lifes dream is o’er

Will the love which I bear thee be alter’d believe

Coll-1839/1/2/5. Poem addressed to Matthew Crawford titled “To Him I Love” in the hand of Louisa Matilda Crawford, 23 July 1817.

Matthew often responded with poems of his own, and seems to have played a collaborative role in Louisa’s writing. She frequently included stanzas of her work in letters to him, asking him to look over and edit them.

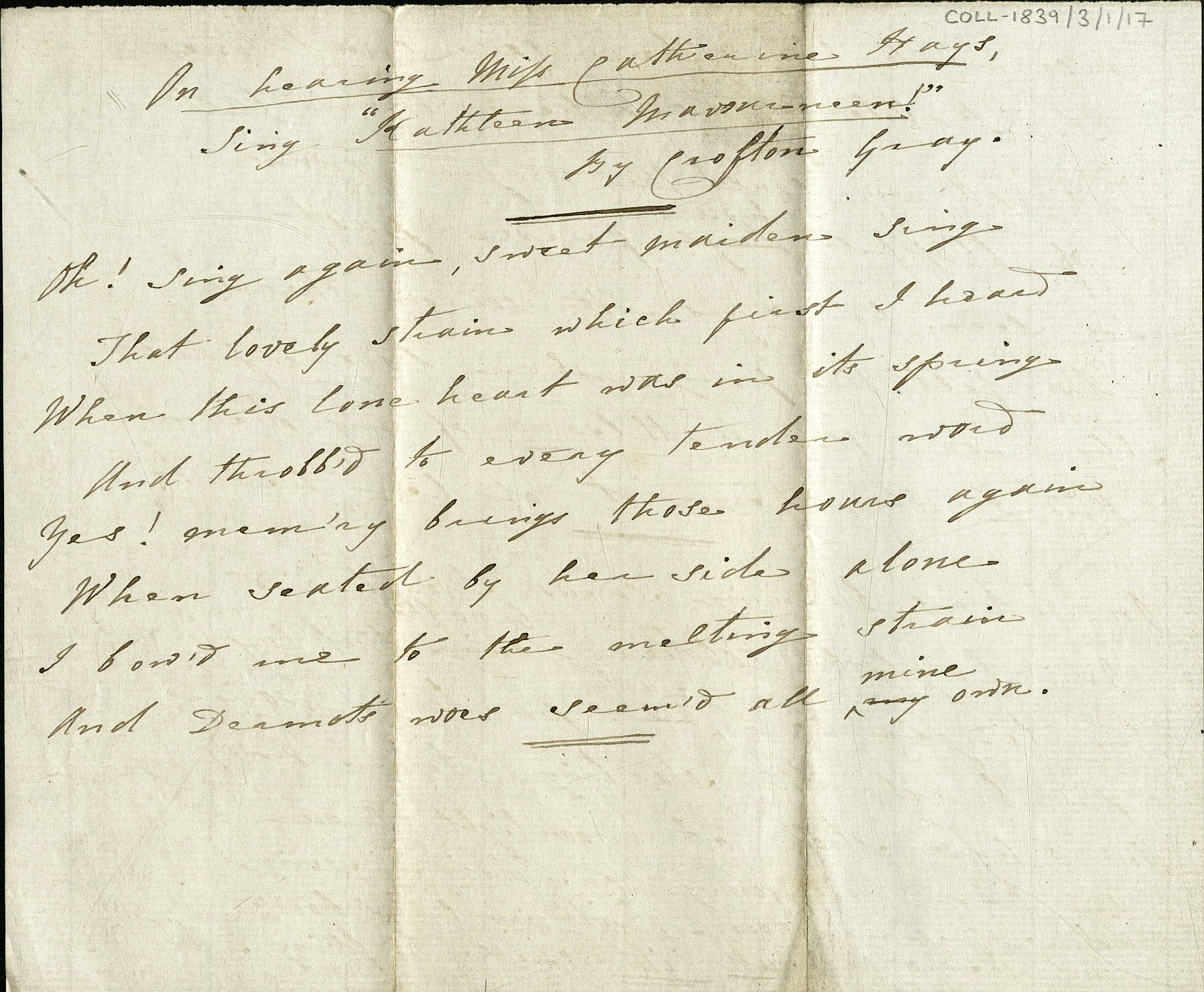

Louisa’s most successful song, “Kathleen Mavourneen,” was set to music by composer Frederick Crouch and enjoyed wide success in America where it was popularised by Irish Soprano Catherine Hayes on her international tours. Recordings of it still exist, and a version by Irish tenor John McCormack (1884-1945) can be found on youtube here. No original version of the song is amongst her papers, although there is a poem titled “On hearing Miss Catherine Hays [sic] sing “Kathleen Mavourneen!”” (Coll-1839/3/1/17). However, the song was frequently attributed solely to Crouch, or erroneously to Annie, Julia, or Marion Crawford.

Coll-1839/3/1/17. Poem titled “On hearing Miss Catherine Hays, sing “Kathleen Mavourneen!” by Crofton Gray” in the hand of Louisa Matilda Crawford, 1837-1857.

Louisa arranged her poems into small series, and the collection includes ten stitched booklets with titles such as “Irish ballads” and “Scotch songs”. Attempts to track down her work can be seen in correspondence with her publishers. In an undated later to magazine editor Mr Emery (Coll-1839/1/1/22) she requests copies of her published songs, writing; “I am not wanting them to give away, but to have them bound up in a volume since I find it impossible to keep single songs…I am going to beat up for recruits in all quarters where my bagatelles have been published, in order that I may have a little memorial to leave to those that will value the gift when I am gone.” A notebook containing 165 poems and songs neatly written in Louisa’s hand seems to be the result of these efforts.

Some outlying items in the collection initially seemed not to relate to Louisa at all, including a 17th century indenture on vellum, recording the sale of a messuage or house between waterman Thomas W Watson and master mariner Josiah Ripley of Stockton-on-Tees. However, a bit of biographical research revealed the answer. Many of these miscellaneous items reference Bayley and Newby, a firm of solicitors operating out of Stockton-on-Tees in the 19th century, which may explain the presence of the indenture. Matthew Crawford’s first cousin, William Crawford Newby (1807-1884) worked at the firm, and it seems that, since the couple were childless, their papers passed to him upon their deaths and thence on to his heirs. The latest item in the collection (Coll-1839/1/3/16) is a 1930 letter by William’s son, who writes:

I enclose a manuscript book written by Mrs Crawford including many well-known songs…Mrs Crawford was a Montagu of the Duke of Manchester family and died in 1857. She was married to Matthew Crawford a barrister. They had independent means which however they frittered away. My late father who was a 1st cousin of Matthew Crawford’s assisted them from time to time and their M.S.S. came to him on their death and through him to me. I am not anxious to part with them, but I am an old man and my family may not attach the same importance to their possession.

This would seem to account for how the papers came to be in the possession of the bookseller and for the few items relating to the Newby’s present in the collection.

Louisa died in 1857, the cause unknown, although Matthew refers to a long affliction of heart disease supplemented by attacks of Bronchitis in an 1846 letter (Coll-1839/2/6). Despite her obvious talent, and the clear enjoyment she derived from her work, she received little notoriety for her song writing during her lifetime and even less so after her death. Alongside gaining invaluable archival skills during this project it has been a pleasure to think that I have been able to increase the visibility of Louisa’s work and make her collection available to interested researchers. Although separated by over two centuries, I have come to know more about Louisa than any person living, and that is a great privilege.

You can see the catalogue of the papers on ArchivesSpace: https://archives.collections.ed.ac.uk/repositories/2/resources/86789

References:

Cleevely, R. J. “Montagu, George.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Online, 23 Sep. 2004, https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/19017. Accessed 19 Jul. 2018.

Crawford, Louisa Matilda Jane. The Metropolitan Magazine. Accessed 19 Jul. 2018.

- “An Auto-Biographical Sketch. Lacock Abbey.” Vol. 12, Jan-Apr. 1835, pp. 400-402, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433081737904;view=1up;seq=412.

- “Autobiographical Sketches Connected with Laycock Abbey.” 14, Sept-Dec. 1835, pp. 306-318, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433081737888;view=1up;seq=322.

- “Autobiographical Sketches.” Vol. 22, 1838, pp. 310-317, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=umn.319510007530342;view=1up;seq=325.

- “Autobiographical Sketches.” Vol. 23, Sept-Dec. 1838, pp. 189-194, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433081737839;view=1up;seq=203.

Cummings, Bruce F. “A biographical sketch of Col. George Montagu (1755-1815).” Zoologisches Annalen Würzburg, vol. 5, 1913, pp. 307–325, http://www.zobodat.at/pdf/Zoologische-Annalen_5_0307-0325.pdf. Accessed 19 Jul. 2018.

“Kathleen Mavourneen.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kathleen_Mavourneen. Accessed 19 Jul. 2018.

Pratt, Tony. Two Georgian Montagus: the manor of Lackham. Wiltshire College, second edition, 2015, https://tinyurl.com/y7tpp39h. Accessed 19 Jul. 2018.

Urban, Sylvanus. “Obituary – Rev. George Newby.” The Gentleman’s Magazine, vol. 26, 1846, pp. 100-101, https://tinyurl.com/yatonw6n. Accessed 19 Jul. 2018.

Written by Daisy Stafford, July 2018.

Women in Scotland: Manufacturing

This is the first post in our new series looking at women in Scotland. If you search for the subject “women” in the Statistical Accounts of Scotland the results are very revealing. They are dominated by references to the work women were doing in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

This work included:

- spinning and weaving;

- being servants;

- in agriculture;

- in the fishing industry;

- in mining.

In the report for Campsie, County of Stirling, there is a very interesting table showing how females in that parish were employed in 1793. (OSA, Vol. XV, 1795, p. 361)

| Wives to the different householders | 410 |

| Daughters, residing in their parents families | 170 |

| Servants in gentlemen’s families | 26 |

| Menial servants to the farmers and different householders in the parish | 110 |

| As sempstresses and mantua makers | 12 |

| Midwives | 3 |

| The remaining 71 are either widows or unmarried women, who reside in cot-houses | 71 |

| Of the married women and young persons, residing in their parents houses, there may be about 150 who pencil calico [at] the print-fields. |

With regards to midwives, not all were trained and some parishes did not have even one! We will look at midwives again in a later post. Other themes we will touch upon in future posts on women in Scotland are health, social status, dress, crime and punishment, and superstitions.

Spinning

In many parishes, it was women who carried out the principle, and sometimes only, form of manufacturing at that time – spinning. In Moulin, County of Perth, “the principal branch of manufacture, carried on in the parish, is the spinning of linen yarn, the staple commodity of the country. In winter, it is the only employment of the women. A woman spins, at an average, 16 cuts the day, the size of the yarn being ordinarily a spindle or 48 cuts from a pound of lint. A woman, who is a good spinner, and employed in nothing else, may earn 3 s. the week; but 1 s. is a high enough estimate of the earnings of a woman, who has a family of 2 or 3 young children to take care of.” (OSA, Vol. V, 1793, p. 61) In Blackford, County of Perth, “the women are the only manufacturers in this parish. From the flax that is raised in it, they spin a good deal of linen yarn, and make many pieces of coarse linen cloth for sale; and, by their industry, raise a part of the rent that is paid to the landlord.” (OSA, Vol. III, 1792, p. 212)

Females started spinning when they were very young, and some carried on til old age. In the parish report for Moulin, County of Perth, you can find the ages of women spinners and their typical work rate: “The women, from 10 years old and upwards, employ themselves in spinning linen yarn, almost wholly for sale, from the beginning or middle of November, till about the end of March, a period of 21 weeks. Of the 789 females above 8 years of age, 272, who are married, may be supposed to spin at the rate of one spindle the week. From the remainder, 517, one fifth part, 103, may be deducted, consisting of girls, old women, etc. whose work cannot be reckoned of any account. The rest, 414, may be supposed to spin at the rate of two spindles.” (OSA, Vol. V, 1793, p. 63) You can discover more information on spinning and the wages paid for this work in many parish reports, such as that of Auchertool, County of Fife (OSA, Vol. VIII, 1793, p. 115), Birsay and Harray, County of Orkney (OSA, Vol. XIV, 1795, p. 324) and Forgan, County of Fife (OSA, Vol. XVI, 1795, p. 95).

By the time of the Statistical Accounts of Scotland changes in spinning had already taken place. These included:

– the amount women spun,with the introduction of the wheel for spinning with both hands (Leslie, County of Fife, OSA, Vol. VI, 1793, p. 43)

– an increase in the use of machinery which replaced the spinning wheel altogether (Dalry, County of Ayrshire, OSA, Vol. XII, 1794, p. 103)

– spinning being replaced by weaving (Carmylie, County of Forfar, NSA, Vol. XI, 1845, p. 371 and Newtyle, County of Forfar, NSA, Vol. XI, 1845, p. 565)

Women were increasingly being employed by large manufacturers. As stated in the parish report of Newtyle, County of Forfar, “since the spinning-wheel gave place to the spinning-mill, females have betaken themselves to weaving, and there are now nearly as many women employed at the loom as men.” (NSA, Vol. XI, 1845, p. 565) In the parish of Kirkmichael, County of Ayrshire, “the large Glasgow warehouses appoint agents here, who give out the cotton to the hand-loom weavers, and are responsible for its manufacture into the required fabric. By this means, a large sum of money is transmitted weekly from Glasgow to the country.” (NSA, Vol. V, 1845, p. 503)

In Avondale, County of Lanark, during the late 1770s “a considerable part of the yarn was manufactured for the behoof of people in the place, and the remainder was carried to the great manufacturing towns. Now [1793] the weavers are almost wholly employed by the Glasgow and Paisley manufacturers, and cotton yarn is the principal material.” (OSA, Vol. IX, 1793, p. 387) In the parish of Glenmuick, County of Aberdeen, women were sent flax for spinning by the manufacturers of Aberdeen (OSA, Vol. XII, 1794, p. 218), whereas in Lochs, County of Ross and Cromarty, “several merchants at Aberdeen send a great quantity of flax annually to a trustee at Stornoway, who distributes it to be spun, not only in this, but in all the parishes of Lewis.” (OSA, Vol. XIX, 1797, p. 278)

Tambouring and flowering muslins

Some women were also learning new skills and being employed to tambour or flower muslins instead. For example, in Hamilton, County of Lanark, “formerly, almost all the weavers manufactured linen only, and either employed themselves, or derived their employment from others on the spot. Now they get employment from the great manufacturers in Glasgow, etc. and cotton yarn is the principal material. Young women, who were formerly put to the spinning-wheel, now learn to flower muslin, and apply to the agents of the same manufacturers for employment.” (OSA, Vol. II, 1792, p. 199) In Kilwinning, County of Ayrshire, “women, and girls from 7 years old, are employed in tambouring muslins. The others flower muslins with the needle. The gauzes and muslins are sent here, for that purpose, by the manufacturers of Glasgow and Paisley.” (OSA, Vol. XI, 1794, p. 160) This was also the case for the parish of Kilbirnie, County of Ayrshire. “This branch of industry is very well paid at present, as, without any outlay or much broken time, an expert and diligent sewer will earn from 7s. to 10s. a week, though probably the average gains, one with another, throughout the year, do not exceed 1s. per day. This employment furnishes the means of decent support to many respectable females, and is decidedly preferred by nearly all the young women, natives of Kilbirnie, to working in either of the manufactories.” (NSA, Vol. V, 1845, p. 717)

Weaving

Women were also involved in the weaving industry, both of cotton and silk. In Hamilton, County of Lanark, “formerly, almost all the weavers manufactured linen only, and either employed themselves, or derived their employment from others on the spot. Now they get employment from the great manufacturers in Glasgow, etc. and cotton yarn is the principal material.” (OSA, Vol. II, 1792, p. 199) With a big increase in demand, especially due to imports to other countries, such as France, this method of manufacture was hard to sustain. For a discussion on this and the fact that hand-loom weavers earned so little, go to the parish report for St Vigeans. (NSA, Vol. XI, 1845, p. 507)

In Dalry, County of Ayrshire, “some years ago, when the silk manufacture flourished, there were above 100 silk weavers in the village, besides a few in the country part of the parish; and these were generally employed by the silk manufacturers in Paisley or Glasgow. But now the number of such weavers is greatly reduced, and cotton weaving has become the chief trade of the place.” (OSA, Vol. XII, 1794, p. 103) The writer of the parish report made the effort to find out the numbers of men, women, and children employed in the different branches of silk and cotton working:

| Silk weavers | 36 |

| Women to prepare the silk yarn for the loom | 8 |

| Cotton weavers | 107 |

| Women and children to prepare the yarn for the loom | 127 |

This highlights the fact that not only women were employed in the weaving industry. In Maybole, County of Ayrshire, “it is very common for women to weave. Boys are put at an early age to the loom, and the hours of working are, more especially in times of depression, very long. I have known the weaver to labour, with little intermission, fourteen and sixteen hours a-day, and after all earn but the miserable pittance of 6s. or 7s. per week, a sum barely adequate to support his family in the meanest way;” (NSA, Vol. V, 1845, p. 371)

As an aside, in Kilmuir, County of Inverness, “perhaps the most interesting custom which prevails in the parish is the manner of fulling, or waulking cloths, which is always performed by females” and is a step in woolen cloth-making. For a description of this process read the parish report (NSA, Vol. XIV, 1845, p. 286).

Introduction of Machinery

It is very interesting to look at the consequences of the introduction of machinery. As reported by the parish of Dundee, County of Forfar, “the general use of machinery has almost wholly superseded that of the spinning-wheel, and sent the females to a less appropriate labour for their support. Old men and old women no longer able to undergo the labour of the loom, and young persons of both sexes not yet strong enough for that work, are employed in winding for the warper and the weaver, and thereby contribute something to the general funds of the family.” (NSA, Vol. XI, 1845, p. 27)

In Renfrew, County of Renfrew, “the first and most important [manufacturing] is the muslin weaving. Connected with this branch, there are 257 looms, of which 176 are called harnessed looms. Each of the whole occupies one man,-except a few, which are wrought by women; and every two occupy one woman winding yarn. But in addition to these, every harnessed loom requires the assistance of a boy or girl, from seven or eight, years of age, up to probably fourteen or fifteen. There are thus, 257 weavers, 176 children drawing, and at least 128 women winding, making in all 561.” (NSA, Vol. VII, 1845, p. 23)

In the parish of Dalry, County of Ayrshire, mule jennies were introduced to spin cotton, “having 15 constantly going, and a small carding mill which goes by water, for preparation. And as they mean to extend their work to the number of 30 jennies, they are now building a carding-mill on a larger scale, to go by water, to answer the purpose of preparation for the above number. The cotton yarn is not manufactured in the place, but is sent to the Paisley or Glasgow markets. Those at present employed in the above work, including men, women, and children, may be about 50.” (OSA, Vol. XII, 1794, p. 104)

A fascinating insight into changes in machinery and employment practices can be found in the parish report for Glasgow, County of Lanark, where “about the year 1795, Mr Archibald Buchanan of Catrine, now one of the oldest practical spinners in Britain, and one of the earliest pupils of Arkwright, became connected with Messrs James Finlay and Company of Glasgow, and engaged in refitting their works at Ballindalloch in Stirlingshire”. (NSA, Vol. VI, 1845, p. 143).

Knitting stockings

At the time of the Old Statistical Accounts of Scotland, parishes located in the County of Aberdeen chiefly manufactured stockings. In Forbes and Kearn, County of Aberdeen, the knitting of stockings was the occupation of which “most of the women, throughout the whole year, and some boys and old men, during the winter season, are employed. They receive for spinning, doubling, twisting and weaving each pair, from 10 d. to 2 s. Sterling, according to the fineness or coarseness of the materials, and the dimensions of the stockings.” (OSA, Vol. XI, 1794, p. 195) In Leochel, County of Aberdeen, “a considerable number of women, chiefly of the aged and poorer class, employ themselves in knitting stockings from worsted, furnished to them by the Messrs Hadden in Aberdeen, and thereby earn annually from L. 70 to L. 100.” (NSA, Vol. XII, 1845, p. 1127)

As reported in the parish of Alford, County of Aberdeen, it was only the manufacture that was carried out by the people of Aberdeenshire. The wool itself was imported from England as it was of better quality. “It is spun and worked into stockings, at a price proportioned to their fineness or coarseness; and the average gain of a good worker, will be 2 s. per week.” (OSA, Vol. XV, 1795, p. 472) In Rayne, County of Aberdeen, “it is supposed, that this article [stockings] may yield to the parish about 400 L. Sterling. The hose are of that coarse kind, which bring for working the pair 12 or 14 pence Sterling; and some of the women will knit two pairs, or two pairs and a half in the week.” (OSA, Vol. XV, 1795, p. 115)

However, the knitting of stockings in the parish of New Machar, County of Aberdeen, was beginning to suffer as “from the invention of stocking looms, the price of women’s work being much reduced, they have begun to direct their attention to spinning, in which they will find their account.” (OSA, Vol. VI, 1793, p. 469) Wars with France and Holland also had an affect on this manufacturing, leading to another diversification. In Rayne, “through the persevering enterprise of few eminent capitalists in Aberdeen, it was succeeded by one a similar kind, viz. the knitting of coarse worsted vests or under-jackets, for seafaring persons, and of blue woolen bonnets, commonly worn by labouring men and boys, which are also knitted with wires, and afterwards milled. This is the common employment of all the aged, and many of the young women in the district of Gazioch; and at the rate of 3d. to 4d. for knitting a jacket, and 1d. to 2.d. for a bonnet, it will yield, with some coarse stockings, to those of this parish alone, about L.600 per annum.” (NSA, Vol. XII, 1845, p. 431)

Other types of manufacturing

Here are some examples of other types of manufacturing undertaken by women, as reported by the parishes of Scotland.

- Needlework

Newton-Upon-Ayr, County of Ayrshire – “As nearly as can be estimated, there are 600 or 700 women, principally girls and unmarried women, employed in hand-sewing for warehouses in Glasgow… The Ayrshire needle-work, so extensively known and justly celebrated, was executed in this parish forty years ago: and it has been gradually improving until the present day. It consists of various patterns sewed on muslin and cambric for ladies’ dresses, babies’ robes, caps, &c. From the year 1815, when point was introduced into the work, the demand for it in London and other parts of England, as well as in Dublin and Edinburgh, has increased to a considerable extent. It is also sent to France, Russia, and Germany, and is exposed to sale in the shops of Paris. This valuable means of employment affords a fair profit to the manufacturer, and gives support to many respectable females, who by dint of industry, can earn from 1s. to 1s. 6d. and, in some cases, 2s. per day. In this work, which is confined to Ayr and its neighbourhood, several hundreds are engaged: and it is calculated that at least from 50 to 60 of them, who are chiefly young women, reside in the parish of Newton.” (NSA, Vol. V, 1845, p. 99)

Kirkcolm, County of Wigton – “The only thing worth mentioning under this head [‘Manufactures’] is, that in almost every house in the village, and indeed through the parish generally, young women are much employed in embroidering muslim webs, obtained from Glasgow or Ayrshire. By embroidering they earn, according to their expertness and the time they can devote to this word, from 8d. to 1s. 3d. a day, and sometimes more.” (NSA, Vol. IV, 1845, p. 119)

- Printing

Bonhill, County of Dumbarton – “Of the hands employed at the printfields [i.e. cotton-printing works], there is nearly an equal number of both sexes. The wages given to the women, at first, were generally at the rate of 3 s. per week. They are now in general paid by the piece, and they may be said to earn 14 s. per month, at an average. The greater part of the women are employed in pencilling. A great variety of colours cannot be put upon the printed cloth without the assistance of the pencil.” (OSA, Vol. III, 1792, p. 447)

Campsie, County of Stirling – “by far the most extensive [printfield] is Letinox-mill Field, which was first established as a print-work about 1786. About 1790 it contained twenty printing tables and six flat presses. At that period, however, a great many women were employed to pencil on colour. This method is now entirely abandoned.” (NSA, Vol. VIII, 1845, p. 254)

- Bleachfields

A bleachfield was an open area of land used for spreading cloth and fabrics on the ground to be bleached by the action of the sun and water. There were many bleachfields in 18th-century Scotland, including those in the parish of Markinch, County of Fife (NSA, Vol. IX, 1845, p. 676), St Vigeans, County of Forfar (NSA, Vol. XI, 1845, p. 509), and Banff, County of Banff, where 40 people were employed (OSA, Vol. XX, 1798, p. 356).

In Tibbermore, County of Perth, “as early as 1774, Huntingtowerfield was formed for the purpose of bleaching linen cloth. This work was carried out with great spirit and success for forty years, by Messrs Richardson and Co., when it was let by the present proprietors, Sir John Richardson of Pitfour, and Robert Smythe, Esq. of Metheven, to Messrs William Turnbull and Son. Under the energy and activity of the present lease-holder, the work has now become one of the first in Scotland. At present about 40 Scotch acres are covered with cloth. The quantity whitened annually is about a million a-half of yards, besides from 80 to 100 tons of linen yarn, for a power-loom factory in the neighbourbood. The number of people employed is about 150, of whom nearly one-third are women and boys… Immediately below this work, on the same Lead, are the flour and barley-mills, the property of Mr Turnbull, the tacksman of the bleachfield, at which a considerable amount of business is done.” (NSA, Vol. X, 1845, p. 1034)

Conclusion

Women played a massive part in the manufacturing industries of Scotland, willing and able to support themselves, their family and their parish. They have had to adapt to changes in demands and technology – and they have done this ably. These qualities are recurrent in future posts, including our next one where we turn our intention to women working in the farming and fishing industries.

Collections

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Projects

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....