Home University of Edinburgh Library Essentials

December 15, 2025

Issues for research software preservation

[Reposted from https://libraryblogs.is.ed.ac.uk/blog/2013/09/18/research-software-preservation/]

Twelve years ago I was working as a research assistant on an EPSRC funded project. My primary role was to write software that allowed vehicle wiring to be analysed, and faults identified early in the design process, typically during the drafting stage within Computer Aided Design (CAD) tools. As with all product design, the earlier that potential faults can be identified, the cheaper it is to eliminate them.

Life moves on, and in the intervening years I’ve moved between six jobs, and have worked in three different universities. Part of my role now includes overseeing areas of the University’s Research Data Management service. In this work, one area that gets raised from time to time is the issue of preserving software. Preserving data is talked about more often, but the software that created it can be important too, particularly if the data ever needs to be recreated, or requires the software in order to interrogate or visualise the data. The rest of this blog post takes a look at some of the important areas that should be thought about when writing software for research purposes.

In their paper ‘A Framework for Software Preservation’ (doi:10.2218/ijdc.v5i1.145) Matthews et al describe four aspects of software preservation:

1. Storage: is the software stored somewhere?

2. Retrieval: can the software be retrieved from wherever it is stored?

3. Reconstruction: can the software be reconstructed (executed)?

4. Replay: when executed, does the software produce the same results as it did originally?

Storage:

Storage of source code is perhaps one of the easier aspects to tackle, however there are a multitude of issues and options. The first step, and this is just good software development, is documentation about the software. In some ways this is no different to lab notebooks or experiment records that help explain what was created, why it was created, and how it was created. This includes everything from basic practices such as comments in the code and using meaningful variable names, through to design documentation and user manuals. The second step, which again is just good software development practice, is to store code in a source code management system such as git, mercurial, SVN, CVS, or going back a few years, RCS or SCCS. A third step will be to store the code on a supported and maintained platform, perhaps a departmental or institutional file store.

However it may be more than the code and documentation that should be stored. Depending on the language used, it may be prudent to store more than just the source code. If the code is written in a well-known language such as Java, C, or Perl, then the chances are that you’ll be OK. However there can be complexities related to code libraries. Take the example of a bit of software written in Java and using the Maven build system. Maven helps by allowing dependencies to be downloaded at build time, rather than storing it locally. This gives benefits such as ensuring new versions are used, but what if the particular maven repository is no longer available in five years time? I may be in the situation where I can’t rebuild my code as I don’t have access to the dependencies.

Retrieval:

If good and appropriate storage is used, then retrieval should also be straightforward. However, if nothing else, time and change can be an enemy. Firstly, is there sufficient information easily available to describe to someone else, or to act as a reminder to yourself, what to access and where it is? Very often filestore permissions are used to limit who can access the storage. If access is granted (if it wasn’t held already) then it is important to know where to look. Using extra systems such as source code control systems can be a blessing and a curse. You may end up having to ask a friendly sysadmin to install a SCCS client to access your old code repository!

Reconstruction:

You’ve stored your code, you’ve retrieved it, but can it be reconstructed? Again this will often come down to how well you stored the software and its dependencies in the first place. In some instances, perhaps where specialist programming languages or environments had to be used, these may have been stored too. However can a programming tool written for Windows 95 still be used today? Maybe – it might be possible to build such a machine if you can’t find one, or to download a virtual machine running Windows 95. This raises another consideration of what to store – you may wish to store virtual machine images of either the development environment, or the execution environment, to make it easier to fire-up and run the code at a later date. However there are no doubt issues here with choosing a virtual format that will still be accessible in twenty years time, and in line with normal preservation practice, storing a virtual machine in no way removes the need to store raw textual source code that can be easily read by any text editor in the future.

Replay:

Assuming you now have your original code in an executable format, you can now look forward to being able to replay it, and get data in and out of it. That it, of course, as long as you have also preserved the data!

To recap, here are a few things to think about:

– Like with many areas of Research Data Management, planning is essential. Subsequent retrieval, reconstruction, and replay is only possible if the right information is stored in the right way originally, so you need a plan reminding you what to store.

– Consider carefully what to store, and what else might be needed to recompile or execute the code in the future.

– Think about where to store the code, and where it will most likely be accessible in the future.

– Remember to store dependencies which might be quite normal today, but that might not be so easily found in the future.

– Popular programming languages may be easier to execute in the future than niche languages.

– Even if you are storing complete environments as virtual machines, remember that these may be impenetrable in the future, whereas plain text source code will always be accessible.

So, back to the project I was working on twelve years ago. How did I do?

– Storage: The code was stored on departmental filestore. Shamefully I have to admit that no source code control system was used, the three programmers on the project just merged their code periodically.

– Retrieval: I don’t know! It was stored on departmental filestore, so after I moved from that department to another, it became inaccessible to me. However, I presume the filestore has been maintained by the department, but was my area kept after I left, or deleted automatically?

– Reconstruction: The software was written in Java and Perl, so should be relatively easy to rebuild.

– Replay: I can’t remember how much documentation we wrote to explain how to run the code, and how to read / write data, or what format the data files had to be in. Twelve years on, I’m not sure I could remember!

Final grading: Room for improvement!

Stuart Lewis, Head of Research and Learning Services, Library & University Collections.

The Royal Medical Society publishes new issue

Res Medica, the Journal of the Royal Medical Society, founded in 1957 has published its first new issue online using the Library’s Journal Hosting Service.

The first new issue features original research (Medical Student Dress code), Clinical review articles, Case reports and Historical articles (Dissection: A Fate worse than Death? Deadly Décor: A Short History of Arsenic Poisoning in the Nineteenth Century).

The Library has also digitised all the back issues of Res Medica. Volumes 1-5 (1957-67) are available in the archives section. The remaining back issues will be made available over the next few months.

All articles, current and historic, have been allocated a DOI (Digital Object Identifier) the first time the Library has made use of its very own DOI prefix.

The new issue and the archives are available via the journal’s site: http://journals.ed.ac.uk/resmedica

If you would like to find out more about using the journal hosting service to publish a new OA peer -reviewed journal or migrate a journal from print to online, please get in touch angela.laurins@ed.ac.uk

Open Access milestone: 10,000th deposit

We are delighted to announce that this month we have deposited the 10,000th open access article in our Current Research Information System (PURE). All this content is made publicly available through the University’s research portal, the Edinburgh Research Explorer. This significant milestone was made possible by the University’s Open Access Implementation project which was funded by a grant from the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills. Each College has been allocated significant resources to recruit extra staff to assist with the sourcing of papers, and to undertake their subsequent upload and description in PURE. These staff have been working with authors, RCUK funded or not, to identify suitable published papers and to make them available online.

This month we have also seen the 7000th item archived in the Edinburgh Research Archive. The PhD thesis by Andres Guadamuz from the School of Law, titled “Networks, complexity and internet regulation scale-free law“, joins one of the largest institutional collections of electronic theses and dissertations in the UK. Together with the content held in PURE, the University of Edinburgh is proud to host one of the largest collections of Open Access materials in the UK with nearly 17,000 full text items freely available to download from our digital repositories.

Peter Higgs and Hunting the Boson

Peter Higgs – one of the University’s most famous living physicists – is the subject of a new exhibition at the National Museum of Scotland. We have loaned one of his earliest papers to this exhibition, which opens today: http://www.nms.ac.uk/our_museums/national_museum/exhibitions/hunting_the_higgs_boson.aspx

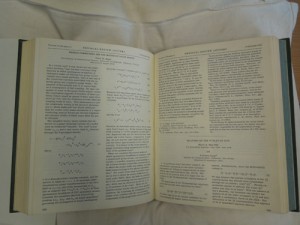

Looking at the Acta Sanctorum – Life of St Cuthbert

We welcomed University of Edinburgh MSc Medieval History students today for a tour of New College Library and the chance to see one of the texts they were studying, the Life of St Cuthbert, in New College Library’s first edition of the Acta Sanctorum, which was on display in the Funk Reading Room. Published in the seventeenth century, the Acta Sanctorum, which contains the first printed edition of this work, is a huge Latin work in sixty-eight volumes examines the lives of saints, organised according to each saint’s feast day in the calendar year. This image shows the large folio volume, still in its original leather binding with metal clasps, open at the Life of St Cuthbert. The Acta Sanctorum is also available online to University of Edinburgh users.

Fire and Brimstone

This week we have been working on some Religious pamphlets for the English Short Title Catalogue. These have come from both the New College Library and here at the Centre for Research Collections, and some of them have the most delightful fire and brimstone titles.

For more information about the ESTC see http://estc.bl.uk/F/GFIV3P5UCLQIQIHNQC1EQBU4HFL4Q9YYCCQ5XD4QM8XJRAED8Q-13504?func=file&file_name=catalogue-options

Susan Pettigrew

RDM in the arts and humanities

The tenth Research Data Management Forum (RDMF), organised by DCC was held in St Anne’s College, University of Oxford on 3 and 4 September. Thus follows an account of proceedings, the goals of which were to examine aspects of arts and humanities research data that may require a different kind of handling to that given to other disciplines, and to discuss how needs for support, advocacy, training and infrastructure are being met.

The tenth Research Data Management Forum (RDMF), organised by DCC was held in St Anne’s College, University of Oxford on 3 and 4 September. Thus follows an account of proceedings, the goals of which were to examine aspects of arts and humanities research data that may require a different kind of handling to that given to other disciplines, and to discuss how needs for support, advocacy, training and infrastructure are being met.

Dave De Roure (Director of the Oxford e-Research Centre) started proceedings as keynote #1. He introduced the concept of the ‘fourth quadrant social machine’ (see Fig. 1) which extends the notion of ‘citizen as scientist’ taking advantage of the emergence of new analytical capabilities, (big) data sources and social networking. He talked also about the ‘End of Theory‘ – the idea that the data deluge is making scientific method obsolete also referencing Douglas Kell’s BioEssay ‘Here is the evidence, now what is the hypothesis‘ which argues that that “data- and technology-driven programmes are not alternatives to hypothesis-led studies in scientific knowledge discovery but are complementary and iterative partners with them.” This he continued, could have major influence on how research is conducted not only in hard sciences but also the arts and humanities. Fig. 1 – From ‘Social Machines’ by Dave De Roure on Slideshare (http://www.slideshare.net/davidderoure/social-machinesgss)

Fig. 1 – From ‘Social Machines’ by Dave De Roure on Slideshare (http://www.slideshare.net/davidderoure/social-machinesgss)

He contends that citizen science initiatives such as Zooniverse (real science online) extend the idea of ‘human as slave to the computer’ however stating that the ‘more we give the computer to do the more we have to keep an eye on what they do.’ De Roure talked about sharing methods being as important as sharing data harnessing the web as lens (e.g. Twitterology) onto society, as infrastructure (e-science/e-research), and as the artifact of study. He went on to highlight innovative sharing initiatives in the arts and humanities that employ new analytical approaches such as:

- the HATHI Trust Research Center which ‘enables computational access for nonprofit and educational users to published works in the public domain now and, in the future’ i.e. take your code to the data and get back your results!

- CLAROS which uses semantic web technologies and image recognition techniques to make the geographically separate scholarly art datasets ‘interoperable’ and accessible to a broad range of users’

- SALAMI (Structural Analysis of Large Amounts of Music Information) which focuses on ‘developing and evaluating practices, frameworks, and tools for the design and construction of worldwide distributed digital music archives and libraries’

De Roure used the phrase ‘from signal to understanding’ to describe the workflow of the ‘social machine’ and went on to described the commonalities that the arts and humanities community have with other disciplines such as working with multiple data sources (often incomplete and born digital), sharing of new and innovative digital methods, the challenges of resource discovery and publication of new digital artifacts, the importance of provenance, and risks of increasing automation. He also highlighted those differences that digital resources in arts and humanities possess in relation to other disciplines in the age of the ‘social machine’ such as specific content types and their relationship to physical artifacts, curated collections and an ‘infinite archive’ of heterogeneous content, publication as both subject and record of research, and the emphasis on multiple interpretations and critical thinking.

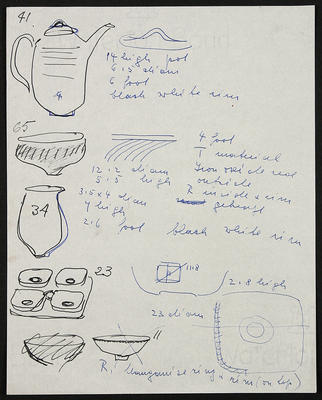

Keynote #2 was delivered by Leigh Garrett (Director of the Virtual Arts Data Service) who opined that little is really known about the ‘state’ of research data in the visual arts. It is both tangible yet intangible (what is data in the visual arts?)! Both physical and digital, heterogeneous and infinite, complex and complicated. He made mention of the Jisc-funded KAPTUR project which was aimed to create and pilot a sectoral model of best practice in the management of research data in the visual arts.

As part of the exercise KAPTUR evaluated 12 technical systems most suited for managing research data in the visual arts including CKAN, Figshare, EPrints, DataFlow. Criteria such as user friendliness, visual engagement, flexibility, hosted solution, licensing, versioning, searching were considered. Figshare was seen as user friendly, visually engaging, intuitive,and flexible however the use of CC Zero licences were seen as inappropriate for visual arts research data due to commercial usage clauses. Whilst CKAN appeared most suited no single solution completely fulfilled all requirements of researchers.

Fig 2. Lucie Rie, Sheet of sketches from Council of Industrial Design correspondence for Festival of Britain, 1951. © Mrs. Yvonne Mayer/Crafts Study Centre.

Available from VADS

Simon Willmoth then gave an institutional perspective from the University of the Arts London. It was interesting that from his experience abstract terms such as research data do not engage researchers, and indeed the term is not in common usage by art and design researchers. His definition in the context of art and design was that research data can be ‘considered anything created, captured or collected as an output of funded research work in its original state’. He also observed that as soon as researchers understand RDM concepts they ask for all of their material (past and present) to be digitised! Echoing earlier presentations regarding the ‘heterogeneous and infinite’ nature of research data in the arts and humanities Simon indicated that artists and designers normally have their own websites, some of the content can be regarded as research data e.g. drawings, storyboards, images, whilst some of it is a particular view dependent upon what it is used for at that instant. He then described the institutional challenges of resourcing (staff, storage, time), researcher engagement, curation (incl. legal, ethical and commercial constraints), infrastructure, and enhanced access. Simon finished with some very interesting quotes from researchers regarding how they perceive their work in relation to RDM e.g.

The work that is made is evidence of the journey to the completed artwork …… it’s kind of a continuous archive of imagery

I try not to throw things out but I often cut things up to use as collage material …. so it’s continual construction and deconstruction. Actually ordering is part of my own creative process, so the whole idea of archiving I think is really interesting

I used to think of a website as something where you display things and now increasingly I see it as a way of it recording the process, so I am using more like a Blog structure. But I am happy to post notes, photographs, drawings, observations and let other people see the process

My sketch books tend to be a mish-mash between logging of rushes notes, detailing each shot, things that I read, things that I hear, books that I’m reading, so it will be a jumble of texts but they’ve all gone in to the making of a piece of work.

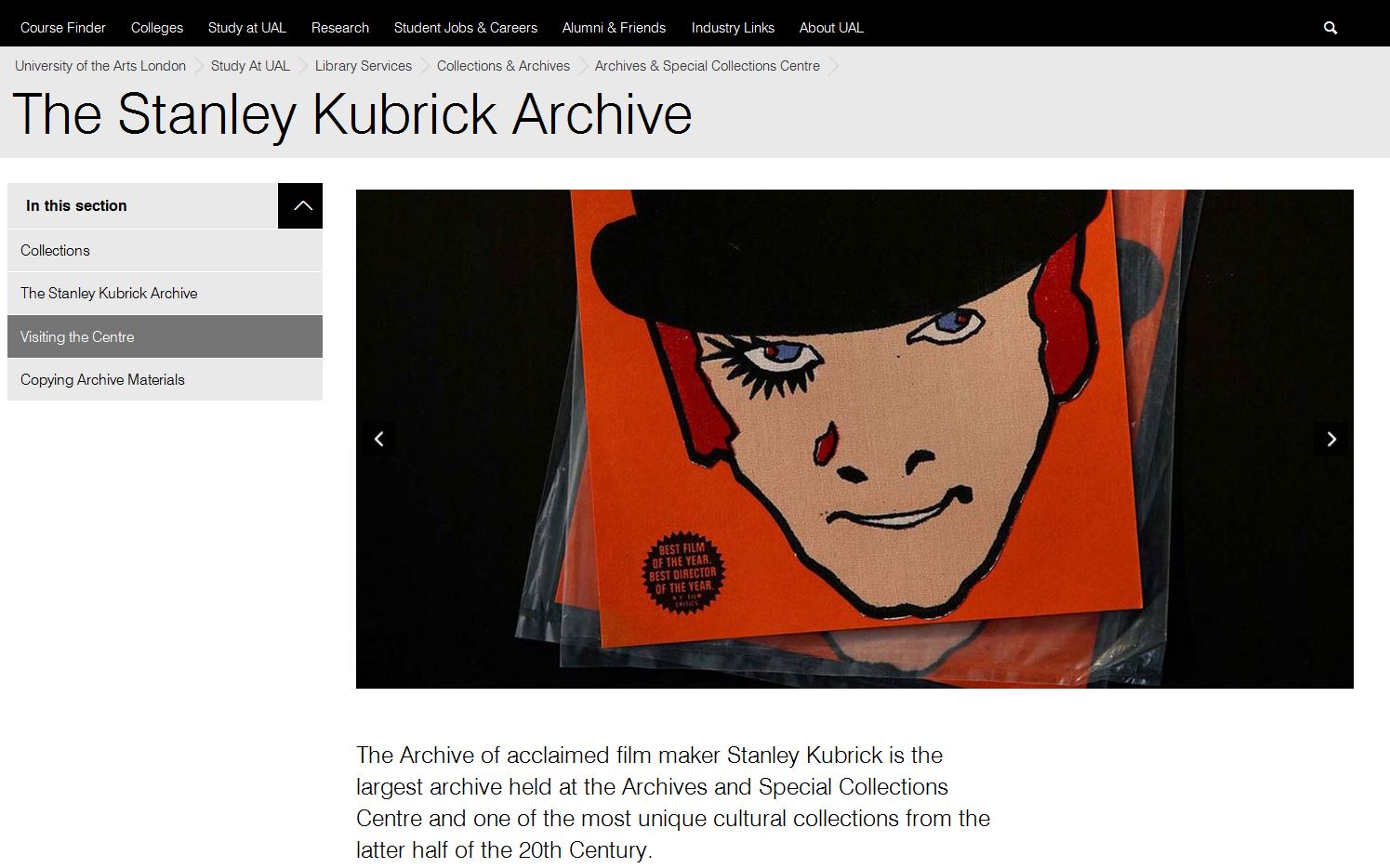

Simon showcased the Stanley Kubrick Archive based at UAL which contains draft and completed scripts, research materials such as books, magazines and location photographs. It also holds set plans and production documents such as call sheets, shooting schedules, continuity reports and continuity Polaroids. Props, costumes, poster designs, sound tapes and records also feature, alongside publicity press cuttings. He argues that the approach of digital copy and physical artifact accompanied by a web catalogue may be the way forward for RDM in the field of art and design.

Julianne Nyhan (UCL) kicked off day two providing a researcher’s view on arts and humanities data management/sharing with particular emphasis on infrastructure needs and wants. She observed that arts and humanities data are artifacts of human expression, interaction and imagination which tends to be collected rather than generated and rarely by those who create the object(s) which can be:

- complex complete with variants, annotations, editorial comment

- multi-lingual

- long lasting

- studied for many purposes

Julianne also reiterated the need to bridge management and sharing on both physical and digital objects as well as more documentation of interpretative processes and interventions (for which she employs a range of note management tools). She went onto say that much of the work done in her own discipline goes beyond disciplinary/academic/institutional boundaries and that the need to retain and appreciate the bespoke should be balanced against need for standardisation.

In terms of strategic developments Julianne saw much mileage in facilitating more research across linguistic borders (through legal instruments at a national/international level) with resultant access to large multilingual datasets from different cultures to inform comparative and transnational research.

Next up Paul Whitty and Felicity Ford (Oxford Brookes University) provided an overview of RDM practices at the Sonic Art Research Unit (SARU). The use of the internet to advertise work is common amongst SARU researchers, musicians, freelance artists. It was however recognised that there lacked any unified web presence such as Ubuweb.

Paul emphasised the need for the internet to be seen as a social space for SARU researchers. At the moment research is disseminated across multiple private websites without consistent links back to the university. Research objects and documentation is split over multiple platforms (e.g. Soundcloud, Vimeo, YouTube). This makes resource discovery difficult except through individual artists web spaces. As of March 2014 research disseminated across multiple private websites will be linked to/from the university with data stored on RADAR, the multi-purpose online “resource bank” for Oxford Brookes thus enabling traceability and impact measurement in terms of the use of digital research assets. As a concluding remark Paul did question whether university IT departments were qualified to provide bespoke website design for arts practitioners and researchers.

Paul emphasised the need for the internet to be seen as a social space for SARU researchers. At the moment research is disseminated across multiple private websites without consistent links back to the university. Research objects and documentation is split over multiple platforms (e.g. Soundcloud, Vimeo, YouTube). This makes resource discovery difficult except through individual artists web spaces. As of March 2014 research disseminated across multiple private websites will be linked to/from the university with data stored on RADAR, the multi-purpose online “resource bank” for Oxford Brookes thus enabling traceability and impact measurement in terms of the use of digital research assets. As a concluding remark Paul did question whether university IT departments were qualified to provide bespoke website design for arts practitioners and researchers.

James Wilson, Janet McKnight and Sally Rumsey then gave an overview of the University of Oxford approach to RDM in the humanities which utilises different business models (extensible or reducible) for different components e.g. DataFinder, Databank, DataFlow, DHARMa. Findings from earlier projects at Oxford indicated that humanities research data tends not to depreciate over time unlike that for harder sciences, is difficult to define, tends to be compiled from existing sources and not created from scratch,and is often not in an optimal format for analysis. Other findings indicated that humanities researchers are least likely to conduct their research as part of a team, least likely to be externally funded, least likely to have deposited data in a repository. Conclusions reached were that humanities researchers were amongst the hardest to reach and that training and support is required to encourage cultural change. Janet McKnight from the Digital Humanities Archives for Research Materials (DHARMa) Project then spoke about enabling digital humanities research through effective data preservation warning that before you impose a workflow in terms of developing systems and processes it would be wise to ‘walk a mile in their [the researcher’s] shoes!’

This was a well-attended and enlightening event, ably organised and chaired by Martin Donnelly (DCC). It offered insight and a wide range of perspectives all of which enhance our understanding of service, of practice, of advocacy, of support in relation to research data management in the arts and humanities.

Slides from all presenters are available from DCC website.

Stuart Macdonald

EDINA & Data Library

New College Library’s Torah Scroll

New College Library’s Torah Scroll (Pentateuch) was on display to visitors today in the Funk Reading Room.

Scrolls such as these are an integral part of Jewish communal life, being read in their entirety in a yearly cycle. The portions of the masoretic texts are divided into weekly portions and their reading in communal worship is followed by a set reading from the prophetic books of the Hebrew Bible.

This scroll is no longer suitable for ritual use, as it is no longer bound onto its original etzim (rollers) or clothed in its original protective and decorative garments. Some letters are damaged, indicating its non-kosher status. Conservation work was undertaken in 2008 to ensure that the scroll was preserved in an appropriate state for study and teaching, and it received new rollers and new box. The funds for this work were raised by the New College Library Book Sale.

The provenance of the scroll is not known, but it may have come to the Library at the same time as other objects from Jewish religious practice in the New College Library objects collection. These include a phylatctory or tefillin, a small, black leather cube-shaped case made to contain Torah texts.

First data curation profile created at Edinburgh

Following our involvement in the pilot presentation of the “RDM Training for Liaison Librarians” course, and taking inspiration from the existing model at Purdue University in the U.S., three liaison colleagues (Marshall Dozier, Angela Nicholson, Nahad Gilbert) and I took up the challenge to create some data curation profiles here at Edinburgh. As at Purdue, it is intended that the creation of such research profiles here will enable us to gain insight into aspects of data management and assist in the assessment of information needs across the disciplines.

To this end I contacted Dr Bert Remijsen, a researcher in linguistics in the School of Philosophy, Psychology & Language Sciences, for which I currently provide liaison support. He had recently deposited a dataset in Edinburgh DataShare and very kindly agreed to be my case study for this pilot.

Drawing on materials at Purdue and Boston Universities, Marshall, Nahad, Angela and I collaborated at some length on the creation of a manageable data curation profile questionnaire for our own use. This was then forwarded by each of us to our respective interviewees ahead of our scheduled meetings with them.

Although I had been involved with RDM issues for some time, I nevertheless approached my own interview with some trepidation. However, I need not have worried, as all went very smoothly indeed! Sending the questionnaire ahead of our meeting ensured that Dr Remijsen had to hand all appropriate information that we might need to consult in the course of the interview.

Although I consigned each of his responses to my iPad as we worked through the questionnaire, Dr Remijsen also supplied a good deal of additional information which I captured in my recording of our meeting. The ability to listen to this a couple of times after the event greatly assisted me both in my later preparation of the final profile and my general understanding of his research and its associated dataset.

Finally, and in contrast to the apprehension that attended this pilot interview, I can honestly say that am now rather looking forward to the next one!

Anne Donnelly, Liaison Librarian, Colleges of Medicine & Veterinary Medicine AND Humanities & Social Science

Welcome to the Main Library

[wpcs]

It’s the start of the new academic year, so we’d like to welcome back existing University of Edinburgh students, and introduce the library to our freshers. You may have noticed some new images on the large screens in the foyer of the Main Library, but if not, they are shown above. We hope that they introduce some of the services offered by the library, and provide you with some interesting snippets about a few of our lesser known services!

Collections

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Projects

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....