Home University of Edinburgh Library Essentials

December 20, 2025

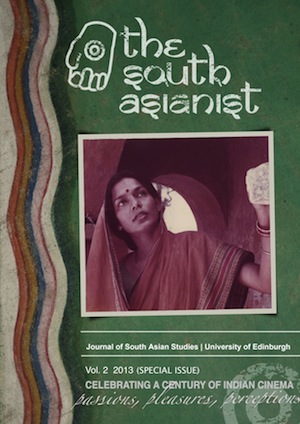

South Asianist celebrates a century of Indian Cinema

The fifth issue of The South Asianist celebrates a century of India cinema with an impressive range of articles, interviews and film reviews.

Senior Indian film-music critic, writer and commentator, Rajiv Vijayakar provides a valuable overview to ‘the role of a song in a Hindi film’ alongside a who’s who of eight decades of Hindi film music.

Founder editor of Stardust and pioneer of film journalism in India, Nari Hira, shares the inside drama behind some of the biggest Bollywood scoops of all time.

While Rajani Krishnakumar, investigates how the nature of the clothing of a heroine and its attributes contribute to the marriage-worthiness of a Tamil woman, using examples from a century of Tamil cinema.

There is also a candid interview with Sai Paranjpye, ‘Queen of humour’ and Ram Mohan, the forgotten ‘father of Indian animation’.

http://www.southasianist.ed.ac.uk

The South Asianist is supported by the University’s Journal Hosting Service: http://journals.ed.ac.uk

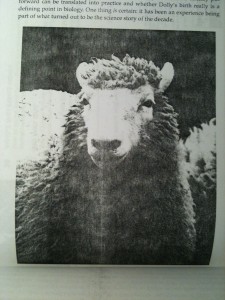

Dollymania – Seven Days that Shook the World

1997 was quite a significant year for the Roslin Institute with “’Dolly, the sheep, ‘…the first mammal cloned from a cell from an adult animal…generated an amazing amount of interest from the world’s media.” (Griffin, Harry. ‘Dollymania’, University of Edinburgh Journal, XXXVIII: 2, December 1997, GB237 Coll-1362/4/1476). And so, it’s been exciting to find articles in the offprints discussing her and the issues of cloning, biotechnology, ethics – Dr. Grahame Bulfield even wrote a report to Parliament on what this breakthrough means for science!

Harry Griffin, former Assistant Director (Science) at the Roslin Institute in 1997’s article, ‘Dollymania’ (cited above) provides an insider’s point of view of how Dolly was produced and the science and research involved. He writes,

Dolly was produced from cells that had been taken from the udder of a 6-year old Finn Dorset ewe and cultured for several weeks in the laboratory. Individual cells were then fused with unfertilised eggs from which the genetic material had been removed and 29 of these ‘reconstructed’ eggs – each now with a diploid nucleus from the adult animal – were implanted in surrogate Blackface ewes. One gave rise to a live lamb, Dolly, some 148 days later. Other cloned lambs were derived in the same way by nuclear transfer from cells taken from embryonic and foetal tissue.

…

On Monday, Dolly provided the lead story in most of the papers and Roslin Institute was besieged by reporters and TV crews from all over the world…. Dolly rapidly became the most photographed sheep of all time and was invited to appear on a chat show in the US. Astrologers asked for her date of birth and PPL’s share price rose sharply. President Bill Clinton called on his bioethics’ commission to report on the ethical implications within 90 days and Ian Wilmut was invited to testify to both the UK House of Commons and the US Congress…. Dolly Parton sad she was ‘honoured’ that we have named our progeny after her and that there is no such thing as ‘baaaaaed publicity’. Sadly, we also received a handful of requests to resurrect relatives and loved pets.

In the article, ‘Seven days that shook the world’ by Harry Griffin and Ian Wilmut in New Scientist, 22 March 1997 also describe the reality of the science of cloning in the face of intense media speculation and reportage.

In the article, ‘Seven days that shook the world’ by Harry Griffin and Ian Wilmut in New Scientist, 22 March 1997 also describe the reality of the science of cloning in the face of intense media speculation and reportage.

Dr. Grahame Bulfield, former Director of the Roslin Institute, wrote several articles in 1997 on biotechnology, ethics, livestock and cloning. In some articles, he writes generally on the techniques of genetic engineering, genome analysis, and embryo manipulations and provides a biological context of these new technologies. (GB237 Coll-1362/4/1394 – 1400). He discusses Dolly more directly in the article, ‘Dit is pas het begin’ in the Dutch journal Natuur & Techniek, No. 8, 1997 (4/1376)  and The Roslin Institute and Cloning an address to the Parliamentary and Scientific Committee in Science in Parliament, Vol. 54, No. 5, September/October 1997 (4/1400). In this particular article he writes specifically about Dolly:

and The Roslin Institute and Cloning an address to the Parliamentary and Scientific Committee in Science in Parliament, Vol. 54, No. 5, September/October 1997 (4/1400). In this particular article he writes specifically about Dolly:

As you know we have been thrown into the middle of public debate recently with a considerable amount of public interest and concern about “Dolly”.  Over a period of about five days we had 3,000 telephone calls, 17 TV crews and we basically ground to a halt. We are perfectly aware now of the issues that are raised , and I don’t believe that a scientific organisation like ours can do anything buy try and be proactive in terms of communicating new biotechnology advances to the public and Government and ensuring the issues involved are widely debated.

Over a period of about five days we had 3,000 telephone calls, 17 TV crews and we basically ground to a halt. We are perfectly aware now of the issues that are raised , and I don’t believe that a scientific organisation like ours can do anything buy try and be proactive in terms of communicating new biotechnology advances to the public and Government and ensuring the issues involved are widely debated.

Thinking about Research Data Asset Registers

[Reposted from https://libraryblogs.is.ed.ac.uk/blog/2013/12/12/thinking-about-research-data-asset-registers/]

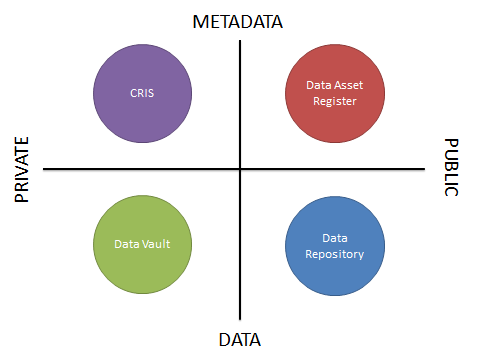

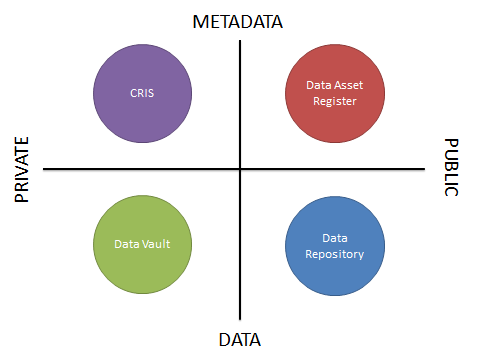

In my last blog post, I looked at the four quadrants of research data curation systems. This categorised systems that manage or describe research data assets by whether their primary role is to store metadata or data, and whether the information is for private or public use. Four systems were then put into these quadrants.

The University of Edinburgh already has two active services from this diagram: PURE, our Current Research Information System and DataShare, our open data repository.

This blog post will start to unpack some of the requirements for a Data Asset Register.

The first aspect to cover is its name. What should it be called? Traditionally systems like this, which only hold metadata records that either just describe, or describe and point to other resources, are known as registers, catalogues, directories, indexes, or inventories.

The University already has a ‘Data Catalogue’, maintained by the Data Library. However this list has a different purpose, to hold details of external data. Oxford University, instead of opting for a name such as this, have instead opted to call their service by the verb ‘find’ – DataFinder. Whilst there may be some brand or service name applied to the system we create at the University of Edinburgh, for now its working title is ‘Data Asset Register’ as one of its main functions will be to allow data creators to ‘register’ their data assets by describing them, and if the data is published online to link to the data.

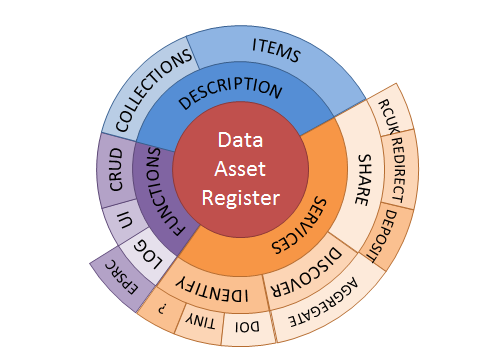

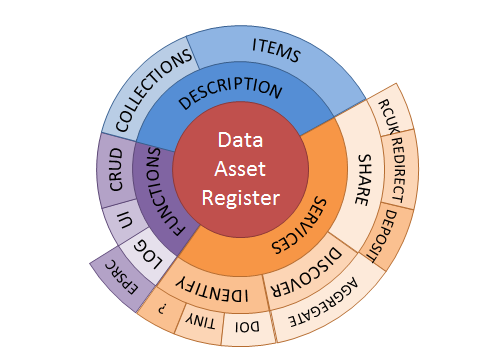

But what should the Data Asset Register provide? The following diagram shows some early thoughts:

The diagram splits this up into three broad areas:

- Description – what the asset register should describe

- Functions – the functions needed to allow data asset description

- Services – the value-added services that will add benefit to people who register their data

Description

The core purpose of the system is to describe data. This is split into two categories: being able to describe single items or data assets, and describing collections of data assets. Many data assets are created on their own, for example a population health longitudinal study. As such, this should be described on its own. In contrast, some data are created in large sets, where it isn’t necessarily useful to describe every part of that set on its own. In this case, the collection as a whole can be described. A good example of this is the Research Data Australia service from the Australian National Data Service.

We’ll need to decide how to describe the data. A likely initial candidate will be the DataCite Metadata Schema, but we may find this needs to be extended to cover extra elements relevant to the University or the discipline of the data asset being described. There will also be requirements coming from a possible UK research data registry, development of which is being led by the Digital Curation Centre.

Functions

In order to enable data asset description, a register will need certain functions. So far three have been identified:

- CRUD: Create / Read / Update / Delete are the basic functions required when manipulating data. The system should allow records of research data to be created, read later, updated, and if needed, deleted.

- User Interface (UI): In order to enable CRUD functionality, a user interface will be required. To be useful, this will need to provide search and display functionality, for example using faceted search and browse.

- Log: Some funders have requirements to keep data for certain lengths of time, or for periods of time that must be reset each time a data set is accessed. For this reason each access of a data asset must be logged by the system. An example is from the EPSRC:

“Research organisations will ensure that EPSRC-funded research data is securely preserved for a minimum of 10-years from the date that any researcher ‘privileged access’ period expires or, if others have accessed the data, from last date on which access to the data was requested by a third party;”

It may also be that the Data Asset Register can be a front-end for our Data Vault too – more about that in another blog post!

Services

Extra value-added services are required in order to make the Data Asset Register useful to people. Our initial thoughts about these services include the following:

- Identify: The ability to assign identifiers to data assets. Some of these identifiers will need to be persistent.

- DOI: DataCite DOIs allow DOIs to be assigned to data assets, in the same way that DOIs are assigned to journal articles. This allows them to be persistently identified over time even if they move between systems, but also allow them to be cited using a well-known identifier.

- TinyURL: A short URL such as those provided by TinyURL or bitly are useful to give easy web identifiers to objects. For example it might be nice to be able to issue URLs such as http://data.ed.ac.uk/abcd.

- Other: Are there any other identifier systems that we should consider using?

- Discover: It is important that the data records held in the Data Asset Register are searchable and can be indexed by external services. This may be by national, international, or discipline-based data aggregators, or by normal web search engines.

- Share: Whilst often the data assets will be described online but kept offline by the researcher, they may wish to share the data. The Data Asset Register may need to facilitate this in a number of ways:

- Deposit: If the data is held in the Data Vault, along with a description in the Data Asset Register, then using a deposit protocol such as SWORD it would be possible to deposit the data into the institutional data repository, or into an external repository. The Data Asset Register can then record the identifier for the hosted data set.

- Redirect: Where the data is hosted online elsewhere, the Data Asset Register could automatically redirect users. For example visiting http://data.ed.ac.uk/abcd could redirect a visitor directly to the repository, rather than showing them just the data asset record description. If the data is not shared openly, then contact details can be provided of the data owner.

- RCUK: Some funders, such as the RCUK members (Research Councils UK) require funded journal papers to include “a statement on how the underlying research materials – such as data, samples or models – can be accessed”. The data asset register could facilitate this by automatically writing statements such as “Details about accessing the data referenced in this paper may be found at http://data.ed.ac.uk/abcd”

It is very early days in our thinking about what features a Data Asset Register should offer, and like many components of a modern research data management infrastructure, there are very few existing examples to look at. Our thoughts will be refined over the coming months so that we can start looking at implementation options. Is there an existing system that can do all of this for us, or is it better to build something new, either alone or with collaborators?

Images available from http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.873617

Stuart Lewis, Head of Research and Learning Services, Library & University Collections.

Thinking about Research Data Asset Registers

In my last blog post, I looked at the four quadrants of research data curation systems. This categorised systems that manage or describe research data assets by whether their primary role is to store metadata or data, and whether the information is for private or public use. Four systems were then put into these quadrants.

The University of Edinburgh already has two active services from this diagram: PURE our Current Research Information System, and DataShare our open data repository.

This blog post will start to unpack some of the requirements for a Data Asset Register.

The first aspect to cover is its name. What should it be called? Traditionally systems like this, which only hold metadata records that either just describe, or describe and point to other resources, are known as registers, catalogues, directories, indexes, or inventories.

The University already has a ‘Data Catalogue’, maintained by the Data Library. However this list has a different purpose, to hold details of external data. Oxford University, instead of opting for a name such as this, have instead opted to call their service by the verb ‘find’ – DataFinder. Whilst there may be some brand or service name applied to the system we create at the University of Edinburgh, for now its working title is ‘Data Asset Register’ as one of its main functions will be to allow data creators to ‘register’ their data assets by describing them, and if the data is published online to link to the data.

But what should the Data Asset Register provide? The following diagram shows some early thoughts:

The diagram splits this up into three broad areas:

- Description – what the asset register should describe

- Functions – the functions needed to allow data asset description

- Services – the value-added services that will add benefit to people who register their data

Description

The core purpose of the system is to describe data. This is split into two categories: being able to describe single items or data assets, and describing collections of data assets. Many data assets are created on their own, for example a population health longitudinal study. As such, this should be described on its own. In contrast, some data are created in large sets, where it isn’t necessarily useful to describe every part of that set on its own. In this case, the collection as a whole can be described. A good example of this is the Research Data Australia service from the Australian National Data Service.

We’ll need to decide how to describe the data. A likely initial candidate will be the DataCite Metadata Schema, but we may find this needs to be extended to cover extra elements relevant to the University or the discipline of the data asset being described. There will also be requirements coming from a possible UK research data registry development of which is being led by the Digital Curation Centre.

Functions

In order to enable data asset description, a register will need certain functions. So far three have been identified:

- CRUD: Create / Read / Update / Delete are the basic functions required when manipulating data. The system should allow records of research data to be created, read later, updated, and if needed, deleted.

- User Interface (UI): In order to enable CRUD functionality, a user interface will be required. To be useful, this will need to provide search and display functionality, for example using faceted search and browse.

- Log: Some funders have requirements to keep data for certain lengths of time, or for periods of time that must be reset each time a data set is accessed. For this reason each access of a data asset must be logged by the system. An example is from the EPSRC:

“Research organisations will ensure that EPSRC-funded research data is securely preserved for a minimum of 10-years from the date that any researcher ‘privileged access’ period expires or, if others have accessed the data, from last date on which access to the data was requested by a third party;”

It may also be that the Data Asset Register can be a front-end for our Data Vault too – more about that in another blog post!

Services

Extra value-added services are required in order to make the Data Asset Register useful to people. Our initial thoughts about these services include the following:

- Identify: The ability to assign identifiers to data assets. Some of these identifiers will need to be persistent.

- DOI: DataCite DOIs allow DOIs to be assigned to data assets, in the same way that DOIs are assigned to journal articles. This allows them to be persistently identified over time even if they move between systems, but also allow them to be cited using a well-known identifier.

- TinyURL: A short URL such as those provided by TinyURL or bitly are useful to give easy web identifiers to objects. For example it might be nice to be able to issue URLs such as http://data.ed.ac.uk/abcd.

- Other: Are there any other identifier systems that we should consider using?

- Discover: It is important that the data records held in the Data Asset Register are searchable and can be indexed by external services. This may be by national, international, or discipline-based data aggregators, or by normal web search engines.

- Share: Whilst often the data assets will be described online but kept offline by the researcher, they may wish to share the data. The Data Asset Register may need to facilitate this in a number of ways:

- Deposit: If the data is held in the Data Vault, along with a description in the Data Asset Register, then using a deposit protocol such as SWORD it would be possible to deposit the data into the institutional data repository, or into an external repository. The Data Asset Register can then record the identifier for the hosted data set.

- Redirect: Where the data is hosted online elsewhere, the Data Asset Register could automatically redirect users. For example visiting http://data.ed.ac.uk/abcd could redirect a visitor directly to the repository, rather than showing them just the data asset record description. If the data is not shared openly, then contact details can be provided of the data owner.

- RCUK: Some funders, such as the RCUK members (Research Councils UK) require funded journal papers to include “a statement on how the underlying research materials – such as data, samples or models – can be accessed”. The data asset register could facilitate this by automatically writing statements such as “Details about accessing the data referenced in this paper may be found at http://data.ed.ac.uk/abcd”

It is very early days in our thinking about what features a Data Asset Register should offer, and like many components of a modern research data management infrastructure, there are very few existing examples to look at. Our thoughts will be refined over the coming months so that we can start looking at implementation options. Is there an existing system that can do all of this for us, or is it better to build something new, either alone or with a collaborators?

Images available from http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.873617

The Story of One

In 1932 and 1947, every 11 year old child in Scotland was given an intelligence test*. This fact is referred to throughout the blog. Its the reason Thomson was famous (he designed the test), it was unique (no equivalent exists anywhere else in the world), and it was done on a huge scale (87, 498 children were tested in the first Scottish Mental Survey, and 70,805 in the second).

For over a decade, Professor Ian Deary and his team have used the results of the tests in Lothian Birth Cohorts 1921 and 1936 to explore why some individuals’ cognitive abilities decline more than others – vital and far reaching research in an increasingly ageing population. Hundreds of people given the intelligence test as a child have participated in the follow on studies, which have explored their cognitive skills, their physical well being, and their lives.

At the very heart of all this data are the people themselves, and what the numbers given in the beautifully neat test ledgers don’t tell us. Deary and his colleagues have previously secured funding for author Ann Lingard to tell the Lothian Birth Cohort’s stories through words, artist Fionna Carlisle through paint, and photographer Linda Kosciewicz-Fleming through the lens.

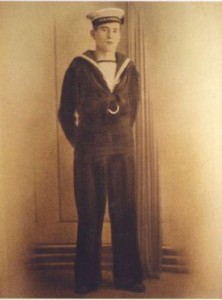

One individual who participated in the 1932 survey, but who was unable to tell his story, was Deary’s Uncle, Richard Deary.

Richard Deary was the son of a miner, and lived with his parents and five siblings

in a one-bedroom miners’ terraced cottage. The family had the most basic of education – Richard would leave school at the age of 14. He, like the thousands of other school pupils who sat the test, was never told his results. He probably never gave them a second thought, and went on to become a miner like his Father. His IQ was an impressive 120.

As an adult, Richard found himself in the midst of World War II:

In the last letter he sent to his parents, he tries to alleviate his parent’s worry, and informs them about a new fangled thing called ‘air graphs’. Two acts of kindness universal from children to their parents the world over. He ends the letter with a ‘cheerio’, and signs ‘your loving son’. Richard died aged 21 when his submarine struck a mine in the Mediterranean Sea 2 months later.

On lecturing at the McEwan Hall on the centenary of the psychology department in November 2006, Deary was presented with this rather wonderful poem by poet Michael Davenport, scribed as he listened to Richard’s story:

A PORTRAIT BY NUMBERS

27.10.2006: a psychologist speaks

of intelligence quotients, cognitive differences,

the Scottish Mental Survey 1932.

Using Powerpoint he illustrates,

shows details from a ledger of the time.

He highlights one boy, Richard,

born 4.4.1921:

number 4 in a class list,

IQ 120 on the Moray House Test.

2.8.1942: Richard’s letter

describes his submarine the ‘Talisman’.

He asks his parents not to worry

if they do not often hear from him

and finishes: ‘Your Loving Son.’

10.9.1942: the ‘Talisman’

leaves Gibraltar reports

a U-boat 5 days later.

18.9.1942: Richard dies at sea,

presumed mined off Sicily.

He’s 21, his navy number:

30938

His nephew, the psychologist, describes

follow-ups of 1930’s survey scores:

correlations with rank and fate in war;

effects of illness, ageing, on the mental skills

of those who still live on.

And with a quiet love

he has included Richard

in this journey of discovery,

his numbers, dates, transmuted

into an elegy.

Michael Davenport

That both history and science are fundamentally about people becomes obvious when looking at a story like Richard’s – or any of the cohorts who shared their lives with Deary and his team. Their stories may not be unusual, but they are all unique, and they allow us to gain some understanding of the humanity behind the numbers – vital if the significance of history and science are to be conveyed to those of us who don’t know much about either!

Every effort has been made to contact Michael Davenport before reproducing his poetry. If there are any objections to this being re-produced in whole or in part, contact Project Archivist, Emma Anthony (Emma.Anthony@ed.ac.uk) who will remove it from the blog.

Hydra, SPSS journal, publishes second issue

Hydra, the postgraduate journal for the School of Social and Political Science has published its second issue on the University’s Journal Hosting Platform.

Hydra’s mission is to strengthen dialogue in SSPS by drawing attention to the excellent postgraduate work going on in the School. The articles in this second issue address a variety of topics, but they do so in a way that is accessible and engaging for a non-specialist audience.

Jacque Clinton begins the issue by examining how historical institutionalism and path dependency have influenced the development of healthcare policy in the UK and US. Nida Sattar follows this with a deconstruction of the complexities of citizenship, focusing on the multi-layered situation faced by the “rejected Biharis” of South Asia.

The final four articles all engage with issues around international aid and development; Katharine Heus critiques the construction of evidence of aid effectiveness in global health interventions, while Megan Wanless examines the World Bank’s approach to dealing with corruption. Katherine Allen interrogates the M-PESA money transfer initiative in Kenya, and Serena Suen rounds off this issue of Hydra by questioning accepted wisdom about the role of women’s education in global development initiatives.

Hydra is a student publication supported by the graduate school. We hope Hydra, like its namesake, will endure and regenerate for years to come.

Welcome to the new Research Data Management Service Coordinator: Kerry Miller

We have great pleasure in welcoming a new member of staff to the research data management programme. Kerry Miller has joined us in the role of Research Data Management Service Coordinator.

Kerry is featured in the latest BITS magazine, sharing details of her new role:

What’s your background?

I’ve undertaken research for various organisations, in industry and charity sectors –

including what is now GlaxoSmithKline and Cancer Research UK as well as the

Ministry of Defence and the British Council. I then joined the Digital Curation

Centre (DCC) in 2011 as an Institutional Support Officer. This involved working

with Higher Education institutions across the UK to help them improve their

Research Data Management policy and practice, in response to Research

Councils UK and other similar requirements.

Tell us about the new position.

My new post, RDM Service Co-ordinator, is a newly-created post, aiming to

bring together and co-ordinate all the different aspects of the research data

management work that’s currently being undertaken throughout the University: lots of

infrastructure improvements, and new tools and support for researchers. There

are things like DataShare, which has been active for a while now, but which we’re

promoting, so more researchers are aware of it and know when to use it. There

are also a few more services that are still in the design phases. You can read all

about the RDM work that is going on via the RDM Blog: datablog.is.ed.ac.uk

What particularly excites you about the new role?

The work we do at the DCC is in many ways quite theoretical; we go out and talk

to institutions about what they ought to be doing, what they need to do to meet

requirements, and that sort of thing, but this new role will be going from talking

the talk to walking the walk; I’ve got to actually do what I’ve been telling people at

other institutions to do! It’s quite scary but also quite exciting; just to see whether

or not I can actually turn that into a real, successful service.

Where exactly will you be based?

I’m within the Research and Learning Section of Library & University Collections, on the lower ground floor of the Main Library. There is a huge number of people involved in the area, but the RDM team itself is small and there aren’t that many people full-time at the moment. RDM is part of a lot of people’s jobs – people like Stuart Lewis and John Scally from the library side, Tony Weir in IT Infrastructure and Robin Rice in the Data Library, but I’ll be one of the few people for whom it’s a full-time, dedicated role.

What do you enjoy doing outside work?

I watch a lot of films, and do a lot of cooking and baking. I’ve been doing a recipe

a week from The Great British Bake Off, with greater or lesser success. I often use

my office colleagues as a waste disposal system!

New staff member: Kerry Miller

Library & University Collections has great pleasure in welcoming a new member of staff to its ranks. Kerry Miller has joined us in the role of Research Data Management Service Coordinator.

Kerry is featured in the latest BITS magazine, sharing details of her new role:

What’s your background?

I’ve undertaken research for various organisations, in industry and charity sectors –

including what is now GlaxoSmithKline and Cancer Research UK as well as the

Ministry of Defence and the British Council. I then joined the Digital Curation

Centre (DCC) in 2011 as an Institutional Support Officer. This involved working

with Higher Education institutions across the UK to help them improve their

Research Data Management policy and practice, in response to Research

Councils UK and other similar requirements.

Tell us about the new position.

My new post, RDM Service Co-ordinator, is a newly-created post, aiming to

bring together and co-ordinate all the different aspects of the research data

management work that’s currently being undertaken throughout the University: lots of

infrastructure improvements, and new tools and support for researchers. There

are things like DataShare, which has been active for a while now, but which we’re

promoting, so more researchers are aware of it and know when to use it. There

are also a few more services that are still in the design phases. You can read all

about the RDM work that is going on via the RDM Blog: datablog.is.ed.ac.uk

What particularly excites you about the new role?

The work we do at the DCC is in many ways quite theoretical; we go out and talk

to institutions about what they ought to be doing, what they need to do to meet

requirements, and that sort of thing, but this new role will be going from talking

the talk to walking the walk; I’ve got to actually do what I’ve been telling people at

other institutions to do! It’s quite scary but also quite exciting; just to see whether

or not I can actually turn that into a real, successful service.

Where exactly will you be based?

I’m within the Research and Learning Section of Library & University Collections, on the lower ground floor of the Main Library. There is a huge number of people involved in the area, but the RDM team itself is small and there aren’t that many people full-time at the moment. RDM is part of a lot of people’s jobs – people like Stuart Lewis and John Scally from the library side, Tony Weir in IT Infrastructure and Robin Rice in the Data Library, but I’ll be one of the few people for whom it’s a full-time, dedicated role.

What do you enjoy doing outside work?

I watch a lot of films, and do a lot of cooking and baking. I’ve been doing a recipe

a week from The Great British Bake Off, with greater or lesser success. I often use

my office colleagues as a waste disposal system!

CENSORED!

Last week I was sent a wonderful book, Deletrix – a collaboration between the artist Joan Fontcuberta, Catalan PEN and Arts Santa Mònica and it explores censorship and violence done to books. Thought provoking, and beautifully illustrated with images that have a strange haunting quality- indeed Fontcuberta challenges the audience as to whether the inherent beauty of the object can redeem the violence done to them. It has got me thinking about the items in our collections that have suffered changes at the hands of censors over the years.

Perhaps the one that immediately springs to mind is Micheal Servetus’ Christianismi Restitutio http://images.is.ed.ac.uk/luna/servlet/s/tv7257. It is thought to be the copy Servetus sent to Calvin; incensed by Servetus’ theories, Calvin ripped out the first 16 pages before he set the wheels in motion to have Servetus burned at the stake using his own books for the fire! (See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michael_Servetus for more information).

However, there are many more censored images in the collection, often the result of religious belief & moral concerns. All the illustrations in the Genesis chapter of this French Bible appear to have God covered with Gold paint http://images.is.ed.ac.uk/luna/servlet/s/q28182

And there are many examples of people being defaced http://images.is.ed.ac.uk/luna/servlet/s/ir0qfd

And there are many examples of people being defaced http://images.is.ed.ac.uk/luna/servlet/s/ir0qfd

Further examples can be found below

http://images.is.ed.ac.uk/luna/servlet/s/75ig3v – perhaps an example of Victorian vandalism?

Or how about this one, where it looks as though the owners name and anathema has been deliberately erased http://images.is.ed.ac.uk/luna/servlet/s/55b726

More information on Deletrix can be found at the links below

http://nathaliepariente.wordpress.com/2012/11/05/nouvelle-exposition-joan-fontcuberta-deletrix/

http://www.flickr.com/photos/pencatala/sets/72157635582961896/with/10022317404/

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vr_AP8dK18w&feature=youtu.be

Many thanks to Ana González Tornero for the beautiful book, the links and information about the Deletrix Project.

Susan Pettigrew

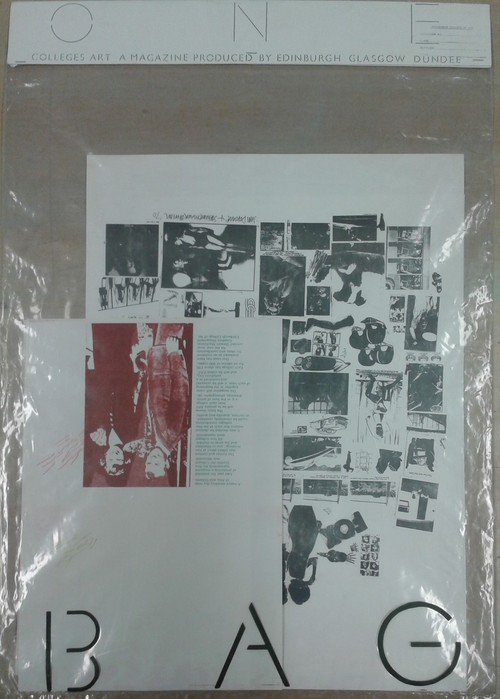

BAG: The Student Magazine

Exciting morning so far! We’ve been sorting through prints and posters for the ECA collections and found something interesting…

Earlier in the year we posted a story in the archives about BAG, the concept for a joint art colleges student magazine between Edinburgh, Glasgow and Dundee in 1970. The magazine was to be called BAG and it would be sold in a polythene bag.

Well we found the prototype ‘BAG’ this morning! And here it is…

We think this is the only one created. The idea was that the contents would be unbound. This prototype contains poetry, illustrations and comment.

Anyone remember talk of BAG at ECA in 1970? If so let us know!

Collections

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Projects

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....