Home University of Edinburgh Library Essentials

December 19, 2025

SPS have top Resource List of semester one!

Sociology 1A had the most used Resource List of semester one, 2014/15, with an average of 67.3 visits per student.

Find out what the course organisers, tutors and students thought about their Resource List and how useful it was for them.

Sociology 1A – Students and Tutors

Interested in creating a successful Resource List for your course? Or just want to find out more about Resource Lists?

See the Resource Lists @ Edinburgh website or their blog: https://libraryblogs.is.ed.ac.uk/resourcelists/

Caroline Stirling – Academic Support Librarian for Social and Political Science

The Working Lives of Ordinary Scots

We know shockingly little of how ordinary Scottish people spent their working lives in the past. We know even less about the work women did. An intriguing comment by the minister of Rogart in the 1790s suggests that whatever it was, it was important. He maintained that a family working for one of the ‘farmers in better circumstances’ were as well off as their masters if, but only if, the wife was industrious. What was it that these industrious women did that was so vital?

I am a great fan of the thick descriptions of life in the 1790s contained in the drily-entitled First Statistical Account of Scotland. They contain surprisingly few statistics and are fantastic sources for glimpsing into the experiences of ordinary people. I thought I would find out how women were spending their time and energy in the eight Sutherland parishes near my home: Creich, Lairg, Rogart, Dornoch, Golspie, Clyne, Loth and Kildonan.

How work was divided up between the sexes was not an issue that was of particular interest to people in the 1790s so was not usually commented on. This leaves historians with the task of identifying little pieces of the jigsaw, the inadvertent remarks of long-dead commentators, and joining them up to create some sort of an incomplete picture. There are a few jobs, like spinning, which seem to be exclusively female and a lot where we don’t really know how labour was divided.

The late eighteenth century was the time of the first industrial revolution. Textile manufacturing on a commercial scale was developing all over Scotland, including in south-east Sutherland. Some Dornoch women processed flax on a small scale, but the biggest impact of this industry was in Brora and Spinningdale. By the 1790s two Brora men were in business as merchants. They imported goods from Aberdeen and London for sale in their shop, and they also imported lint. They paid as many as two to three thousand women to spin the lint in their own homes and then re-exported the yarn to the south. On the banks of the Kyle of Sutherland, David Dale tried to take the textile business one step further by manufacturing, rather than just preparing, raw materials. The venture came to a fiery end, but it provided an income not only for those who worked in the cotton factory, but for women who could earn up to four or fivepence a day in their own homes. One remarkable spinner allegedly produced 10,000 spindles annually.

Fishing boats pulled up in Brora harbour, 1890. From here the two merchants would have shipped the lint processed by local women.

Photo credit: Historylinks Image Library http://www.historylinksarchive.org.uk/picture/number6307.asp

Other women left the region to earn wages. Many young people migrated seasonally to the big arable farms of the Lowlands. Apparently as soon as the boys of Rogart and Creich were strong enough for heavy work they took off in search of higher wages, returning in the winter, to ‘live idle with their friends’. The young, single girls went south later in the summer ‘to assist in cutting down and getting in the crop’. Presumably when they were a little older they put these skills to use getting in their own harvests.

Most of the information in the Statistical Accounts about work does not distinguish between what men did and what women did. Most likely they worked together, or broke big jobs down into smaller tasks: some for men and some for women.

Housebuilding, peat digging, crop raising and tending livestock were probably all shared tasks. Most of these involved hard, physical work and the co-operation of all family members. Houses in east Sutherland were built with turf and ‘thatched with divot’. To build a house you needed to dig turf, transport it, build, then after three or so years when the house was somewhat falling into disrepair and the materials were coated with soot, pull it down and spread the materials on the fields as fertiliser.

Providing heat and light also required the hard labour of all who could provide it. In the parish of Dornoch, the peat mosses which supplied winter fuel were awkwardly distant from the fertile coastal strip where the bulk of the population lived. If nineteenth-century practices of peat digging are anything to go by, men dug and women stacked. By the end of the summer when the peats had dried, the people and their ‘small, half-starved horses’ trekked into the upland areas. They walked from their homes in the evening, camped out in the open, and loaded up the baskets tied to the horses’ backs the next morning.

Monochrome negative of photograph of the harvesting in the Highlands. From Miss Lyon’s collection. (1920)

Photo credit: Historylinks Image Library http://www.historylinksarchive.org.uk/picture/number3158.asp

Women and men spent most of the year in agricultural tasks. There is no way that men alone could do all the ploughing, planting, sowing, manuring, weeding, harvesting, threshing, storing or drying for the oats, bere, pease, potatoes, beans and rye that people grew and ate in Sutherland. These crops fed themselves and the stock of pigs, goats and sheep which provided for the family, plus the black cattle whose sale in the southern markets raised cash for goods and rent. As elsewhere in the Highlands, women played crucial roles in summering these cattle on the low hills of east Sutherland, especially through dairying.

We still don’t really know precisely why Rogart’s minister thought an industrious wife was so vital. However, the clues in the Statistical Accounts at least suggest what tasks women did, and why communities divided work in the gendered ways that they did.

Dr Elizabeth Ritchie, Centre of History, University of Highlands and Islands

We hope you have enjoyed this post: it is characteristic of the rich historical material available within the ‘Related Resources’ section of the Statistical Accounts of Scotland service. Featuring essays, maps, illustrations, correspondence, biographies of compliers, and information about Sir John Sinclair’s other works, the service provides extensive historical and bibliographical detail to supplement our full-text searchable collection of the ‘Old’ and ‘New’ Statistical Accounts.

Mary Lyon (1925-2014) – Edinburgh connections

We were saddened to hear recently of the passing of Mary Lyon, a distinguished mouse geneticist. Born in 1925 in Norwich, Mary was best known for her X-chromosome inactivation hypothesis, which proposed that one of the two X chromosomes in every cell of female mammals is inactivated. Mary worked at the MRC Radiobiology Unit in Harwell from 1955 until her death, becoming head of the genetics division (later the Mammalian Genetics Unit) in 1995. What is perhaps not so well-known is that her early work took place in Edinburgh, at the Institute of Animal Genetics.

Mary began at the Institute in 1948 to continue her PhD on mouse genetics, which she had begun in Cambridge under R.A. Fisher. This was after studying zoology at Girton College, Cambridge (although, as women were not allowed to be official members of the University until 1948, Mary was only awarded a ‘titular degree’). The Institute of Animal Genetics, then under the directorship of C.H. Waddington, possessed superior histology facilities, which she needed for her work. Mary ended up staying for a further five years after her PhD, working with Toby Carter on a project funded by the Medical Research Council to study mutagenesis in mice (this was at a time, following the Second World War and atomic bombs in Japan, of great concerns about the effects of nucelar fallout in the atmosphere). In a 2010 interview, Mary Lyon stated that, out of her whole career, it was her time in Edinburgh that she enjoyed the most: ‘It was a very lively academic atmosphere…a big genetics lab and a lot of able and enthusiastic geneticists.’ The above photograph, from the Institute of Animal Genetics archives, shows Mary (far right) with (right to left) Institute Librarian Stella Dare-Delaney, Mary’s assistant Rita Phillips, and distinguished molecular geneticist and embryologist Margaret Perry.

Toby Carter’s Mutagenesis Unit moved south to Harwell in order to find more space in which to breed and keep mice, taking Mary with it, as well as Rita Phillips. Scientists working with Douglas Falconer in Edinburgh had been the first to discover X-linked mutants in mice. With this discovery in mind, Mary, noticed that female mice carrying X-linked coat colour mutations had mottled coats. Male mice which inherited a mottled coat (i.e. a mutant gene on their single X-chromosome) all died, but the females survived. This must mean that the female possessed one, inactivated, mutant gene on one X-chromosome, but a normal gene on the other chromosome, which was activated – therefore a female mouse needs only one X chromosome for normal development. This inactivation of one of the two X chromosomes in the cells of females is still called ‘Lyonisation’, and the discovery had profound implications for understanding the genetic basis of X-linked diseases such as Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Grahame Bulfield, later director of the Roslin Institute, first positioned the mouse muscular dystrophy mutant on the X-chromosome using Mary’s stock of mouse X-chromosome mutants.

Over the next six decades, Mary also made important studies of Chromosome 17 and ‘the t-complex’, which had significant bearings on the understanding of non-Mendelian inheritance (a departure from the expected one-to-one ratio due to the abnormal segregation of chromosome pairs). Mary’s work pioneered the use of the mouse as a model organism for advances in cell and developmental biology as well as molecular medicine, and laid the foundations for comprehending the human genome. She chaired the Committee on Standardised Genetic Nomenclature for Mice from 1975 to 1990, was made a foreign associate of the US National Academy of Sciences, and was a Fellow of the Royal Society (being the 28th woman to be elected such). In 2004, the Mary Lyon Centre opened at Harwell, a leading international centre for mouse genetics, and in 2014 the UK Genetics Society created the Mary Lyon medal.

Mary died on Christmas Day 2014, aged 89, ‘after drinking a glass of sherry, eating

her Christmas lunch and settling down in her favourite chair for a nap’.

The University of Edinburgh’s remembrance of Mary Lyon can be read here: http://www.ed.ac.uk/news/staff/obituaries/2015/mary-lyon-030215

Clare Button

Project Archivist

Sources:

– ‘The Gift of Observation: An Interview with Mary Lyon’, Jane Gitschier (2010), http://journals.plos.org/plosgenetics/article?id=10.1371/journal.pgen.1000813

– ‘Mary F. Lyon (1925-2014): Grande dame of mouse genetics’, Sohaila Rastan, Nature, 518, (05 February 2015)

Capturing the Moment on Glass Plate Negatives

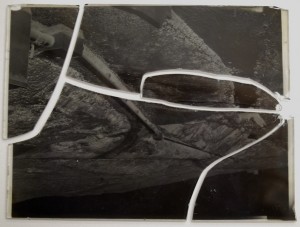

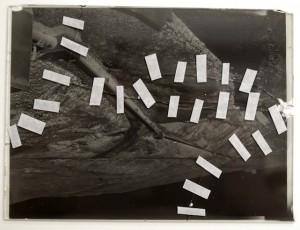

I recently attended a one-day workshop at the RCAHMS conservation studio regarding the preservation and conservation of glass plate negatives. The day was split roughly into two parts, with the first half of the day dedicated to lectures in digitising glass plate negative collections, preservation, identification of damage and the conservation and stabilisation techniques available for broken negatives. Practical sessions were conducted by ICON intern, Marta Garcia-Celma during the second part of the day when the group were given a practical demonstration of the cleaning procedures of glass plate negatives, gelatine consolidation, and a stabilisation technique for cracked and broken negatives called the sink mount with pressure binding technique. This system of encapsulation uses blotter to create a tight fitting frame-mount and two pieces of clean glass to sandwich the broken glass plate negative within, allowing the plate to be safely handled, digitised and stored. I shall discuss how to make this enclosure in more detail during this blog post as I had never undertaken such a procedure before, finding the experience insightful, rewarding, and very fiddly! First of all though, chaps, you need to find yourself a broken glass plate negative. Here’s one I prepared earlier! Cue Blue Peter theme tune…

Once you have completed surface cleaning the glass side of the pieces of broken plate using a very soft squirrel hair brush and dampened cotton wool, you may begin to create your flush repair. You start by wiping the surface of two new pieces of glass with IMS (industrial methylated spirit), which should be cut slightly larger than your glass plate negative. Next, you should place your broken glass plate negative emulsion side down onto a piece of blotter (about 1cm larger than your plate and the same size as your new pieces of glass) and splint the broken pieces back together using filmoplast p90 tape. This is a delicate and time consuming process, however the key thing to remember is to avoid sticking the splints down too much, otherwise you’ll have a real job of pulling them off again later!

To create a tight fit within the blotter sink mount, you should carefully score around the edge of the negative using a scalpel blade then cut out the centre of the blotter and discard – you only need the outer rim to act as a frame-mount for your glass plate negative. Your glass plate negative should now fit snugly in the newly cut centre of the blotter. This part of the process is probably the trickiest, as it is very important for the mount to fit tightly and perfectly around the glass to avoid movement – a saggy mount will not do! Then once you have placed your newly mounted glass plate negative on to your clean sheet of glass and removed your splints you can begin the procedure of binding your glass sandwich together!

With your broken glass plate negative snugly within its blotter mount and now sandwiched between two new sheets of glass you can bind the edges together using a pasted out strip of silver safe photographic paper; roll your glass plate along the pasted paper and secure as you go. This part is also fiddly mainly because the pasted out strip is damp and weak. So don’t be namby-pamby about it, you don’t want to lose grip of your sandwich whilst smoothing down the binding paper! Once the whole glass sandwich is bound you can snip and fold the corners to make them neat and pretty.

And voilà! Your broken glass plate negative is now easy to handle and store, which is quite jolly considering its prior sorry shattered state and always worth a shot if you ask me….

Post by Samantha Cawson, Conservation Intern

Bicentennial of the birth of Professor Edward Forbes (1815-1854), marine biologist, geologist, natural historian and biogeographer

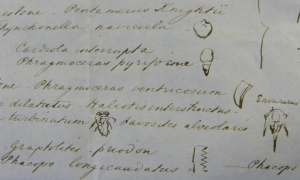

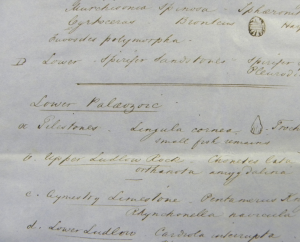

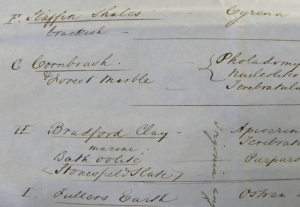

DRAWING & SKETCHING, STUDYING & RESEARCHING, TRAVELLING & DREDGING, DESCRIBING MOLLUSCS & SHELLFISH, MUSEUM CURATION & PALAEONTOLOGY, PRESIDING OVER SCIENTIFIC BODIES & CLASSIFIYING TERTIARY FORMATIONS, AND LECTURING – ALL IN A SHORT BUT PACKED 39-YEARS… PROFESSOR EDWARD FORBES… ‘A BRILLIANT GENIUS’…

12 February 2015 marks the 200th anniversary of the birth in Douglas, Isle of Man, of Edward Forbes the marine biologist, geologist, naturalist and pioneer in the field of biogeography (the study of the geographic distribution of plants and animals). On the Isle of Man, Forbes is most noted for his cataloguing of the marine life inhabiting the island and the neighbouring sea.

Born on 12 February 1815, Edward Forbes received his early education in Douglas and even in those early years he showed a taste for natural history, literature and drawing. His parents were said to have been so impressed with the artistic talent behind the drawings and caricatures on his schoolbooks that they sent him to London to study art with ambitions for a place in the Royal Academy Schools. His artistic talent was not good enough for the Royal Academy however, so in 1831 he entered Edinburgh University as a medical student instead.

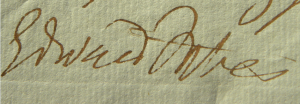

Signature of Edward Forbes, from the Isle of Man, Edinburgh University session 1831-32. The signature was written in November 1831, and Forbes was the 115th student to matriculate. Volume ‘Matriculation 1829-1846’.

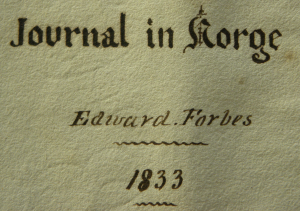

His 1832 vacation was spent looking at the natural history of the Isle of Man, and in 1833 he travelled to Norway, sailing on a brig from Ramsey on the Isle of Man to Arendal in Norway. He described his Norwegian trip in a journal – his Journal in Norge – illustrated with his own sketches. Barely four lines into his journal, started on Monday 27 May 1833, we find the first natural history log of the trip, ‘Caught some Gurnards … on one of them were several parasite insects’.

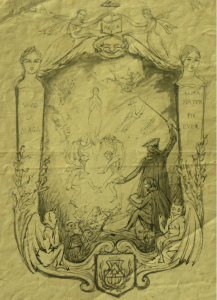

Title to the journal Edward Forbes wrote on his trip to Norway, 1833. From the ‘Journal in Norge’. Dc.6.91

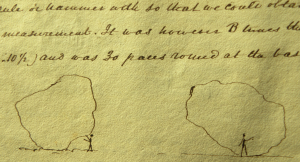

On Saturday 22 June 1833, Forbes was in the country around Stavanger, ‘hilly but apparently fertile’ where the rock was chiefly gneiss and mica slate. There he found an immense boulder though with ‘neither rule or hammer’ he ‘could obtain neither specimen or correct measurement’. From the ‘Journal in Norge’. Dc.6.91

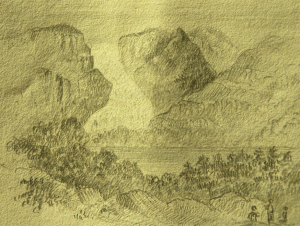

On Tuesday 3 July 1833, in the evening, Forbes arrived at a little village in the vicinity of the Glacier at Bondhus on Hardanger Fjord. He sat down at ‘a table plentifully supplied with the staple food of the country’. From the ‘Journal in Norge’. Dc.6.91

Other natural history during these years included dredging work in the Irish Sea, and travels in France, Switzerland and Germany. Indeed he spent the winter of 1836-37 in Paris studying at the Le Jardin des Plantes which included attending the lectures of De Blainville (1777-1850) and Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire (1772-1844), and looking at the geographical distribution of animals. He then travelled to the south of France and across the Mediterranean to Algeria collecting specimens. A born naturalist rather than a student of medicine, he had earlier – by 1836 – abandoned the notion of a medical degree and instead devoted his studies to science and literature.

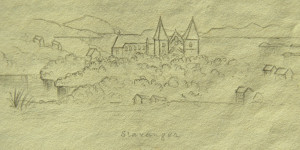

Sketch by Forbes of Stavanger, Norway, including Stavanger Cathedral (Stavanger domkirke) in his ‘Journal in Norge’. Dc.6.91

Sketch by Forbes of Kronborg Castle (Hamlet’s Castle) at Helsingør, Denmark, in his ‘Journal in Norge’. Dc.6.91

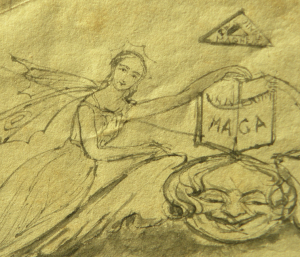

While at Edinburgh University, Forbes and John Percy were joint publishers of a magazine, called the University Maga, which was published weekly during session 1837-1838. Its frontispiece was sketched by Forbes and contained subjects within it which were similar to those commented on by Sir Archibald Geikie much later on in 1915. Forbes’s animals and figures are ‘in all kinds of comical positions and employments’, said Geikie (quoted from Manx Quarterly, p.329. Vol.V. No.20, 1919).

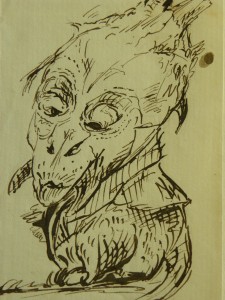

Detail from the cover of the ‘University Maga’ (pen and ink drawing) is shown here. Dc.4.101 Forbes.

Investigations by Forbes into the natural history of the Isle of Man occupied much of his time, leading to a volume on Manx Mollusca once he was back in Edinburgh. The remainder of the 1830s saw him touring Austria, delivering scientific papers and lecturing in Newcastle, Cupar and St. Andrews and to the Edinburgh Philosophical Association, on subjects such as terrestrial pulmonifera in Europe, the distribution of pulmonary mollusca in the British Isles, and British marine life. In 1839 he obtained a grant for dredging research in the seas around the British Isles, and towards the end of that year he published a paper on British mollusca in which he established a division of the coast into four zones.

The 1840s opened for Forbes with a series of lectures in Liverpool. He also visited London where he met other scientists, and he travelled and did more dredging. In 1841 he published a History of British Starfishes based on his own observations – and many observed for the first time – and that year too he was appointed as naturalist on board HMS Beacon engaged in surveying work in the eastern Mediterranean and the Aegean Sea. He also explored upland Turkey, looking at its antiquities, freshwater mollusca, plants and geology.

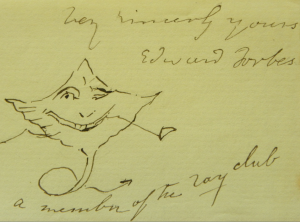

Small pen and ink sketch of a ray and reference to membership of the ‘ray club’ on a letter, showing the signature of Edward Forbes. The ‘ray club’ may refer to the Ray Society, a scientific text publication society founded in 1844. It was named after John Ray, the 17th-century naturalist. Gen.524.3.

Back in Britain again, Forbes took a post as Curator of the museum of the Geological Society, and in 1844 he became Palaeontologist to the Society. He presented a report on his research in the Aegean to the British Association and lectured before the Royal Institution on his studies of the littoral zones and his discoveries in these. Also in 1844 he became a Fellow of the Geological Society and Palaeontologist to the Geological Survey, and in 1845 a Fellow of the Royal Society. He was also voted as a member of the Athenaeum Club. Dredging in Shetland and around the west of Scotland occurred during this period, as did the presentation of a course of lectures at the London Institution and then also at King’s College.

Forbes was instrumental in the founding of the Palaeontological Society in 1847, and in 1849 he was working on the position in geological time-scale of the Purbeck Group (the Purbeck Beds) famous for its fossils of reptiles and early mammals. More dredging occurred, this time in the Hebrides, and more lecturing, and preparation for the on-going co-publication of a History of British Mollusca which appeared 1848-1852. His many dredging excursions contributed to this work. Between 1849 and 1850 he was busy arranging a new geological museum at the Geological Survey premises in Jermyn Street, London, which would open in 1851. Before that though, more dredging occurred in the western Hebrides, and more lecturing in the Royal Institution.

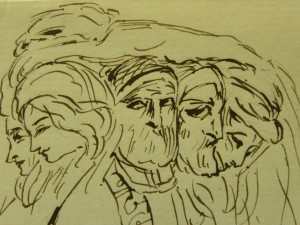

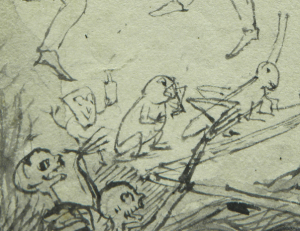

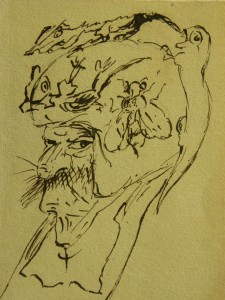

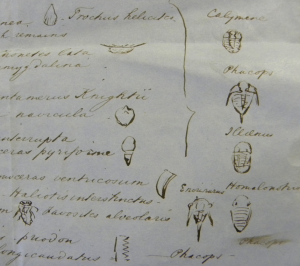

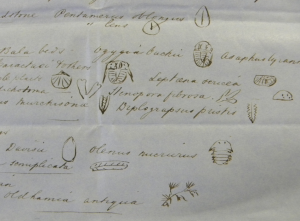

Throughout their work, ‘Memoir of Edward Forbes, F.R.S.’, Macmillan & Co., Cambridge and London, 1861, Archibald Geikie and George Wilson include vignettes and tail-pieces by Edward Forbes at chapter-ends… Probably not unlike these here. Gen.524.3.

Throughout their work, ‘Memoir of Edward Forbes, F.R.S.’, Macmillan & Co., Cambridge and London, 1861, Archibald Geikie and George Wilson include vignettes and tail-pieces by Edward Forbes at chapter-ends… Probably not unlike these here. Gen.524.3.

In the summer of 1851, Forbes became Lecturer in Natural History in a new School of Mines (the Government School of Mines and Science Applied to the Arts, later the Royal School of Mines) which had been formed out of the efforts of geologist Sir Henry De La Beche (1796-1855). Indeed the staff of the Geological Survey became the Lecturers and Professors of the School of Mines, and the new School was located in the same Jermyn Street premises as the museum.

The winter of 1852-1853 saw Forbes working on the classification of the tertiary formations, and still a comparatively young man – in his late-30s – he was elected as President of the Geological Society in 1853. The following year, in 1854, he became Professor of Natural History at Edinburgh University, succeeding Professor Robert Jameson who held the Chair for nearly half a century from 1804 until 1854. In his History of the University of Edinburgh 1883-1933, Arthur Logan Turner would write that Forbes was among ‘a remarkable group of outstanding men’ whose ‘individual influence’ after the mid-19th century would help science become ‘seriously recognised in the University’ – the other remarkables included Lyon Playfair (Chair of Chemistry), P. G. Tait (Chair of Natural Philosophy), and Archibald Geikie (Chair of Geology). Another historian – Sir Alexander Grant – would describe Forbes as ‘a brilliant genius’.

Professor Edward Forbes delivered his inaugural lecture on 15 May 1854 but during the meetings of the Geological section of the British Association held in Liverpool he suffered from a fever. Forbes would not live to see publication of his work on the tertiary formations, and after only a few month’s tenure as Professor – after only a few days into the winter session 1854-1855 – he had to cancel his lectures owing to ill-health. He died shortly afterwards on 18 November 1854 at the age of 39. The brilliant genius ‘was extinguished’, his light ‘having just shown itself above the horizon’, Sir Alexander Grant was to write later.

Professor Edward Forbes was buried in Edinburgh’s Dean Cemetery.

A student of Edward Forbes, James Hector (1834-1907), later Sir James Hector the Scottish geologist, naturalist, and surgeon, would name a mountain after his former Professor. Hector had participated in the Canadian Palliser Expedition to explore new railway routes for the Canadian Pacific Railway, and named the 8th highest peak in the Canadian Rockie Mountains after Forbes. Mount Forbes (3,612 metres) is in Alberta, 18 km southwest of the Saskatchewan River crossing in Banff National Park.

Organised by the Department of Environment, Food and Agriculture in partnership with Manx National Heritage, the Isle of Man Natural History and Antiquarian Society and the Society for the Preservation of the Manx Countryside, the Edward Forbes Bicentenary Marine Science and Conservation Conference will take place 12-14 February 2015 at the Manx Museum, Douglas, Isle of Man. The Museum will also stage pop-up displays on the life and legacy of Edward Forbes during the Conference.

Dr. Graeme D. Eddie, Assistant Librarian Archives and Manuscripts, Centre for Research Collections

Sources:

- Manx Worthies. Professor Edward Forbes (from the Manx Note Book, by A. W. Moore): Edward Forbes [accessed 2 Feb 2015]

- Eric L. Mills. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Forbes, Edward (1815-1854), marine biologist, geologist, natural historian [accessed 2 Feb 2015]

- Grant, Sir Alexander. Story of the University of Edinburgh during its first three hundred years in 2 volumes. London: Longmans Green and Co., 1884. Vol.II., p.434-435.

- Turner, A. Logan. History of the University of Edinburgh 1883-1933. Edinburgh: Oliver & Boyd, 1933. p.240.

- Material contained within Coll-133, Papers of Edward Forbes, Edinburgh University Library (Centre for Research Collections)

The National Monument of Scotland

The Digital Imaging Unit has digitised many architectural drawings held in University of Edinburgh special collections over the years. They always present a challenge because of thier scale. They offer a fascinating glimpse of history in relation to many of the buildings in Edinburgh that we are familiar with on a daily basis. I think many of us have a positive relationship with the National Monument more commonly known as the Acropolis on Calton Hill. Read More

About the Project

Welcome to the Fairbairn Blog.

William Ronald Dodds Fairbairn (1889-1964) was a leading psychoanalyst whose pioneering work helped children suffering from trauma in the early 20th century. His personal library including works by Freud and Jung is held by Edinburgh University Library. His papers, diaries and correspondence are in the National Library of Scotland. This project, funded by the Wellcome Trust, will see these collections fully catalogued and conserved and made accessible online through a new collaborative website.

New donation of Scottish poetry

Tessa Ransford, poet activist and founder of the Scottish Poetry Library, has gifted to the University of Edinburgh her personal collection of poetry pamphlets. This is a major new acquisition for Special Collections which strengthens our excellent existing holdings of modern literature and Scottish poetry.

‘No one has done more for the cause of poetry in Scotland than Tessa Ransford’ asserted Dorothy McMillan in the Scottish Review of Books in 2008, and her influence on contemporary poetry in Scotland has been profound. Born in India, Tessa has spent most of her life in Scotland, and has published numerous collections of poetry since the 1970s. She founded the Scottish Poetry Library in 1984 and directed it until 1999. She has edited Lines Review poetry magazine and set up the Callum Macdonald Memorial Award to encourage the publishing of poetry in pamphlets (www.scottish-pamphlet-poetry.com). As a student at the University of Edinburgh she was influenced by philosopher John Macmurray, whose papers we also hold.

This collection includes many rare works produced in small editions, and numerous copies signed or annotated by the writer – as well as letters and other handwritten documents. It will be kept together as a new named special collection.

http://www.wisdomfield.com/biograph.html

http://www.scottishpoetrylibrary.org.uk/poetry/poets/tessa-ransford

Collections

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Projects

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....

Combining two of our most popular Pop-up Library sessions from last semester you will get the opportunity to play our 1980s inspired game, learn how tagging and metadata can help your studies and get up close and personal with some highlights from the University’s Art Collections.

Combining two of our most popular Pop-up Library sessions from last semester you will get the opportunity to play our 1980s inspired game, learn how tagging and metadata can help your studies and get up close and personal with some highlights from the University’s Art Collections.