We know shockingly little of how ordinary Scottish people spent their working lives in the past. We know even less about the work women did. An intriguing comment by the minister of Rogart in the 1790s suggests that whatever it was, it was important. He maintained that a family working for one of the ‘farmers in better circumstances’ were as well off as their masters if, but only if, the wife was industrious. What was it that these industrious women did that was so vital?

I am a great fan of the thick descriptions of life in the 1790s contained in the drily-entitled First Statistical Account of Scotland. They contain surprisingly few statistics and are fantastic sources for glimpsing into the experiences of ordinary people. I thought I would find out how women were spending their time and energy in the eight Sutherland parishes near my home: Creich, Lairg, Rogart, Dornoch, Golspie, Clyne, Loth and Kildonan.

How work was divided up between the sexes was not an issue that was of particular interest to people in the 1790s so was not usually commented on. This leaves historians with the task of identifying little pieces of the jigsaw, the inadvertent remarks of long-dead commentators, and joining them up to create some sort of an incomplete picture. There are a few jobs, like spinning, which seem to be exclusively female and a lot where we don’t really know how labour was divided.

The late eighteenth century was the time of the first industrial revolution. Textile manufacturing on a commercial scale was developing all over Scotland, including in south-east Sutherland. Some Dornoch women processed flax on a small scale, but the biggest impact of this industry was in Brora and Spinningdale. By the 1790s two Brora men were in business as merchants. They imported goods from Aberdeen and London for sale in their shop, and they also imported lint. They paid as many as two to three thousand women to spin the lint in their own homes and then re-exported the yarn to the south. On the banks of the Kyle of Sutherland, David Dale tried to take the textile business one step further by manufacturing, rather than just preparing, raw materials. The venture came to a fiery end, but it provided an income not only for those who worked in the cotton factory, but for women who could earn up to four or fivepence a day in their own homes. One remarkable spinner allegedly produced 10,000 spindles annually.

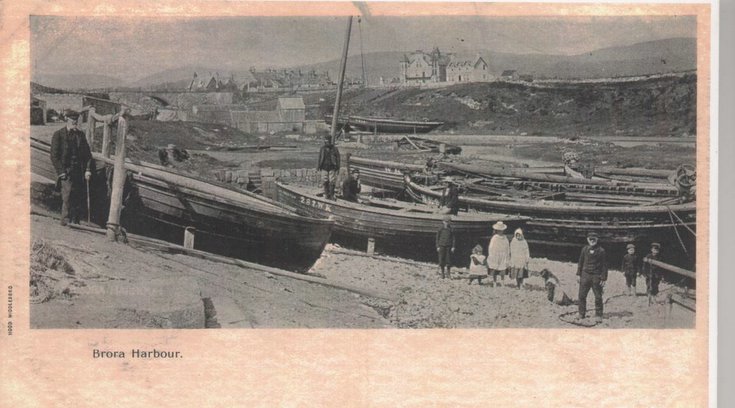

Fishing boats pulled up in Brora harbour, 1890. From here the two merchants would have shipped the lint processed by local women.

Photo credit: Historylinks Image Library http://www.historylinksarchive.org.uk/picture/number6307.asp

Other women left the region to earn wages. Many young people migrated seasonally to the big arable farms of the Lowlands. Apparently as soon as the boys of Rogart and Creich were strong enough for heavy work they took off in search of higher wages, returning in the winter, to ‘live idle with their friends’. The young, single girls went south later in the summer ‘to assist in cutting down and getting in the crop’. Presumably when they were a little older they put these skills to use getting in their own harvests.

Most of the information in the Statistical Accounts about work does not distinguish between what men did and what women did. Most likely they worked together, or broke big jobs down into smaller tasks: some for men and some for women.

Housebuilding, peat digging, crop raising and tending livestock were probably all shared tasks. Most of these involved hard, physical work and the co-operation of all family members. Houses in east Sutherland were built with turf and ‘thatched with divot’. To build a house you needed to dig turf, transport it, build, then after three or so years when the house was somewhat falling into disrepair and the materials were coated with soot, pull it down and spread the materials on the fields as fertiliser.

Providing heat and light also required the hard labour of all who could provide it. In the parish of Dornoch, the peat mosses which supplied winter fuel were awkwardly distant from the fertile coastal strip where the bulk of the population lived. If nineteenth-century practices of peat digging are anything to go by, men dug and women stacked. By the end of the summer when the peats had dried, the people and their ‘small, half-starved horses’ trekked into the upland areas. They walked from their homes in the evening, camped out in the open, and loaded up the baskets tied to the horses’ backs the next morning.

Monochrome negative of photograph of the harvesting in the Highlands. From Miss Lyon’s collection. (1920)

Photo credit: Historylinks Image Library http://www.historylinksarchive.org.uk/picture/number3158.asp

Women and men spent most of the year in agricultural tasks. There is no way that men alone could do all the ploughing, planting, sowing, manuring, weeding, harvesting, threshing, storing or drying for the oats, bere, pease, potatoes, beans and rye that people grew and ate in Sutherland. These crops fed themselves and the stock of pigs, goats and sheep which provided for the family, plus the black cattle whose sale in the southern markets raised cash for goods and rent. As elsewhere in the Highlands, women played crucial roles in summering these cattle on the low hills of east Sutherland, especially through dairying.

We still don’t really know precisely why Rogart’s minister thought an industrious wife was so vital. However, the clues in the Statistical Accounts at least suggest what tasks women did, and why communities divided work in the gendered ways that they did.

Dr Elizabeth Ritchie, Centre of History, University of Highlands and Islands

We hope you have enjoyed this post: it is characteristic of the rich historical material available within the ‘Related Resources’ section of the Statistical Accounts of Scotland service. Featuring essays, maps, illustrations, correspondence, biographies of compliers, and information about Sir John Sinclair’s other works, the service provides extensive historical and bibliographical detail to supplement our full-text searchable collection of the ‘Old’ and ‘New’ Statistical Accounts.

Really loved this insight . They were tough people for sure.

Everyone had to contribute. I’m in no doubt women did whatever they possibly could do. We all still do….

I find their diet interesting. Found out that the Oats were Black Oats. These are now fed to racehorses.

Must try the Pease meal and Bere!

So glad you enjoyed the post, Karen. You may like to have a read of our series of posts on Scotland’s food and drink. We are also planning to publish posts on women in Scotland. Watch this space!