Home University of Edinburgh Library Essentials

December 17, 2025

What’s New in DiscoverEd – September 2017

The latest release of DiscoverEd includes some very useful new features and functionality. Read on for full details…

1. New Filter for Special Collections Material

A new “Special Collections” filter has been added to the Show Only filters section. Selecting this filter allows you to limit the results of your search to material held at the Centre for Resource Collections (CRC) and other special collections in the Main Library, the Library Annexe (our off-campus storage facility), New College Library, Moray House Library and ECA Library.

2. Exclude/Include Multiple Filters

It is now possible to select multiple filters to include or exclude items from your search results:

To include a filter, hover on the filter name and click on the tick box which appears to the left.

To exclude a filter, hover over the filter name and click on the Exclude This.. icon which appears to the right.

You can exclude or include as many filters as you wish. When you are finished making your selections, click on the APPLY FILTERS button to apply your selected filters to your search results.

3. Sticky Filters

It is now possible to apply a set of filters to a search and make them “sticky” for the remainder of your DiscoverEd session. For example, you may wish to make the “Full Text Online” Show Only filter and the “Books” Resource Type filter sticky. This would result in subsequent searches being limited to electronic books.

To make filters sticky:

- Run an initial search in DiscoverEd and apply the filter(s) you wish.

- In the “Active filters” section, hover over the name of a filter you wish to make sticky. A small opened padlock icon will appear. Click on this icon and it will change to a closed padlock icon. Repeat this process for each of the filters you want to make sticky.

If you want to remove sticky filters at any stage in your session, simply repeat the above process, this time changing the closed padlock icon back to the open padlock icon.

4. Sort items in My Favourites

It is now possible to sort the items you have stored in My Favourites by Date Added, Title and Author.

To use this functionality, simply go to your My Favourites and use the Sort by dropdown menu to apply the sort order you require.

5. Support for RSS Feeds

DiscoverEd now allows you to harvest the results of a saved search in your chosen RSS reader application.

- Make sure you are signed in to DiscoverEd.

- Run a search and click on Save this search to My Favourites.

- Go to My Favourites and select the SAVED SEARCHES tab.

- Click on the RSS icon on the right hand side of the display.

- Follow your usual procedure for setting up an RSS feed in your browser or dedicated RSS reader application.

You can also create an RSS feed for any of the searches you have already saved in My Favourites by following steps 3-5 above.

Interactive Integrated Pest Management

The final post from Sophie Lawson, our conservation Employ.ed intern, in this week’s blog…

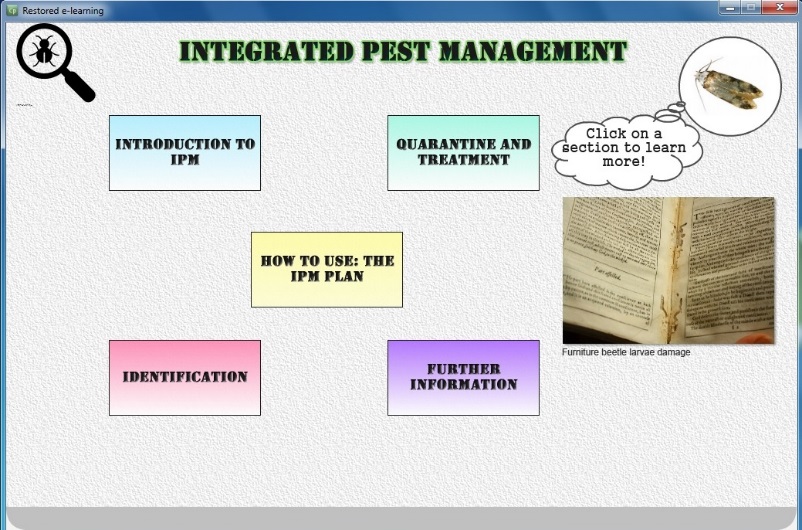

We are approaching the end of our Conservation E-learning project, with a completed trial resource being prepared to go to our first focus group. The resource focuses on providing the user with an introductory level of knowledge of Integrated Pest Management, with a focus on the problem of insect pests in Special Collections storage. More specifically, the resource aims to provide a wider knowledge of the following: an introduction to Integrated Pest Management (or IPM), how an IPM plan is implemented, pest identification procedures and the quarantine and treatment procedures within an institution.

The interactive menu-based home screen of the trial e-learning resource

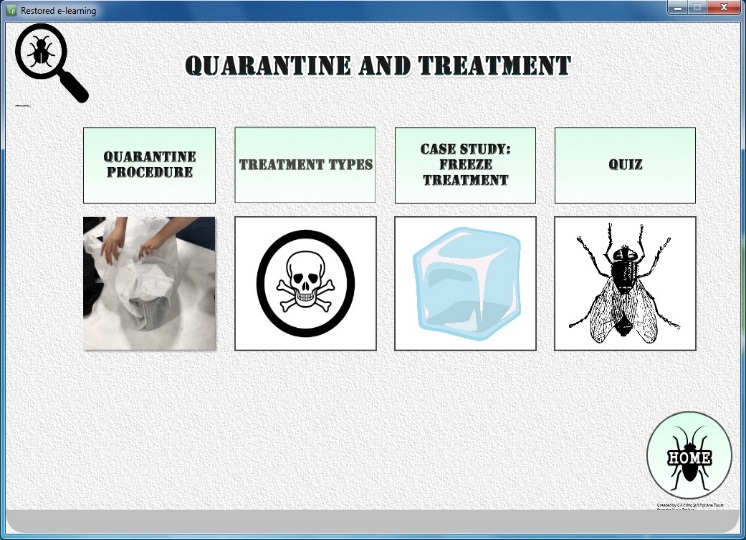

Quarantine and Treatment clickable menu screen

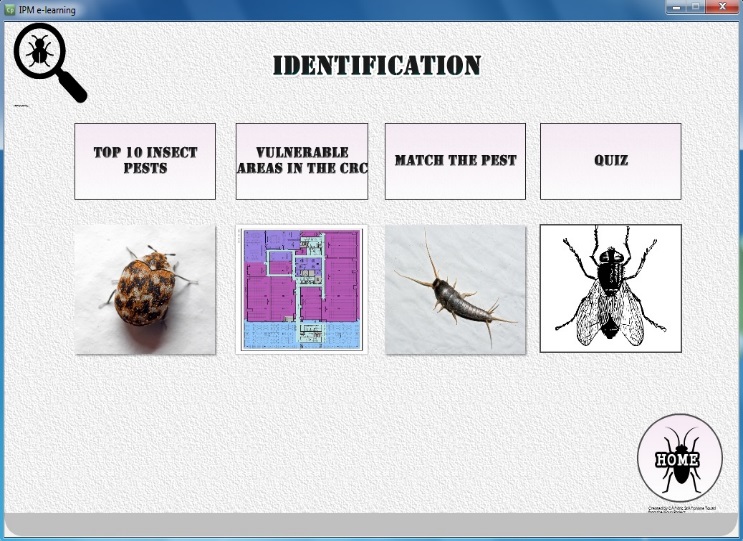

Identification clickable menu screen

On trial: Codices Vossiani Latini Online

Thanks to a request from a member of staff in Classics, we currently have trial access to Brill’s Codices Vossiani Latini Online which publishes all 363 codices which form the world-famous Latin part of Isaac Vossius’ manuscript collection held at Leiden University Library.

Thanks to a request from a member of staff in Classics, we currently have trial access to Brill’s Codices Vossiani Latini Online which publishes all 363 codices which form the world-famous Latin part of Isaac Vossius’ manuscript collection held at Leiden University Library.

You can access this resource via the E-resources trials page. Access is available both on and off-campus.

Trial access ends 27th September 2017.

Screenshot from VLQ 079 – Aratea, c. 850.

Isaac Vossius (1618-1689) was a Dutch scholar and collector of manuscripts, maps, atlases and printed works, who for a few years was also the court librarian to Queen Christina of Sweden. According to contemporaries Vossius’s extensive library was the best in Europe, if not the world, and after he died his library of books and manuscripts was sold to the University of Leiden. Read More

Christian-Muslim Encounters in Texts

This week, the School of Divinity hosts the first conference of the Global Network for Christian-Muslim Studies, Reframing Christian-Muslim Encounter : Theological and Philosophical Perspectives.

In a new display in New College Library, we can see some Christian-Muslim encounters in texts from New College Library’s collections. These texts record Christian reactions to the Muslim encounters Turkish military campaigns brought close to home, and the preparations of Christian missionaries to venture into Muslim territories.

Robert, of Chester, active 1143, Peter, the Venerable, approximately 1092-1156, Bibliander, Theodorus (1504-1564), Luther, Martin (1483-1586) Melanchthon, Philipp (1497-1560), Machumetis Saracenorum principis, eius’ que successorum vitae, doctrina, ac ipse Alcoran.

(Basel, 1550) MH.163

At the same time as Martin Luther was challenging the authority of the papacy using scripture, the military campaigns of the Turks were approaching closer into Europe. Luther approached this encounter with Islam by inquiring into Islamic texts, which culminated in his involvement in this publication in Latin of the Qur’ān. Read More

Dealing with Data Conference 2017 – Call for Papers

[Update: Deadline for submissions has now been extended to Thursday 5th October]

Date: Wednesday 22nd November 2017

Location: Playfair Library

Themes:

- Balancing openness with privacy – How do you meet funder demands for open data without exposing research participants sensitive information?

- Informed consent – Is it possible to get informed consent from a research participant if you don’t know how their data may be used in future?

- Is your research data Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable (FAIR)? – How easy is it to apply the FAIR data principles to your research data?

- Is open data changing the way you do research? – Has open access to research data helped your research? Have you struggled to access data which ought to be open? Is the need to make our data open taking you away from conducting new research?

- How have research data tools impacted on your productivity? What tools do you need to work with your research data effectively?

Format: Presentations will be 15 minutes long, with 5 minutes for questions. Depending on numbers, thematic parallel strands may be used. Presentations will be aimed at an academic audience, but from a wide range of disciplines. Opening and closing keynote presentations will be given.

Call for proposals:

Open research data is not an end in itself, its purpose is to push research forward by making existing research data available to others so that they can build upon it and in doing so make new discoveries not even envisaged by the original data creators.

The Dealing with Data 2017 one-data conference is your opportunity to talk about how the drive towards open data is affecting your research. How do you balance competing demands for data openness with the right to privacy of research participants? Has access to open data already helped in your research, or are the demands for openness discouraging you from undertaking certain types of project?

Are new tools providing new and exciting ways to work with your data or are you struggling to find tools to help you do what you need?

This is your opportunity to tell fellow researchers how you are benefiting from, or struggling with, the ever changing research data environment.

Please send abstracts (maximum 500 words) to dealing-with-data-conference@mlist.is.ed.ac.uk before Thursday 5th October 2017. Proposals will be reviewed and the programme compiled by Friday 3rd November 2017.

Kerry Miller

Research Data Services Coordinator

Library & University Collections

Sydney Goodsir Smith Stands for Rector

In 1951, students voting for a new Rector of Edinburgh University faced a choice between a quite extraordinary range of candidates. The election of actor Alistair Sym in 1948 had put an end to a long tradition of electing career politicians or military men. This time, in the wake of Sym’s success, nominees included Nobel-prize winning scientist Sir Alexander Fleming, novelist Evelyn Waugh, music hall entertainer Jimmy Logan, and politician and spiritual leader, Sir Sultan Muhammed Shah, Aga Khan III.

Also on the ballot was Lallans poet Sydney Goodsir Smith, who had come to prominence three years earlier through his collection Under the Eildon Tree, one of the most significant works of the Scottish Literary Renaissance. Edinburgh University Archives have recently purchased a copy of Smith’s campaign leaflet, adding to our major collection of Smith papers (Coll-497).

Smith was born in New Zealand but moved to Scotland in 1928 when his father Sir Sydney Alfred Smith (1883-1969) was appointed Professor of Forensic Medicine at Edinburgh University. Smith himself began a medical degree at Edinburgh University but soon abandoned it to study Modern History at Oxford. The ‘Message from the Candidate’ in the campaign leaflet alludes to his brief Edinburgh career:

During my short and somewhat hectic time as a medical student here, I must have been inoculated with the bug of not exactly ‘study’ so much as just ‘being a student’, for I seem to have remained a student, of one thing or another, ever since.

Smith thus presents himself as ‘a real student’s rector’, who, unlike his ageing and out-of-touch rivals, will provide an ‘effective student voice’ on the University Court. There is a second strand to his campaign, however, which voters may have struggled to reconcile with his stance as a spokesman for student interests.

The ‘Message from the Candidate’ also states that Smith’s nomination is:

single evidence of the increased regard held for Scottish literature – too long the Cinderella of Scottish life and thought – by the student body of what used to be Scotland’s capital in fact as well as name

The leaflet, in fact, foregrounds Smith’s literary credentials. The cover photo portrays Smith in his study, resplendent in a smoking gown, and surrounded by tottering piles of books. Beneath the caption ‘Sydney Goodsir Smith: Poet, Scholar, Artist, Wit’ are endorsements from major literary figures of the day, Edith Sitwell, Neil M. Gunn, Duncan Macrae, Sorley Maclean, and Hugh MacDiarmid.

Conspicuously, the least political endorsements are placed first. Sitwell claims that ‘it would honour poetry should [Smith] be elected’, Gunn declares that ‘to vote for a Scots poet of so rare a vintage as Sydney Goodsir Smith I should find irresistible’. For actor Duncan Macrae, Smith is alone among the candidates in possessing ‘the distinction of genius’. Maclean too credits Smith with ‘creative genius’ along with an ‘irresistible personality’ and a place among ‘the very finest critical intelligences’.

Only the final endorsement from Hugh MacDiarmid, himself a rectorial candidate in 1935 and 1935, gives a hint of Smith’s political position. Presenting Smith as ‘an outstanding figure in the Scottish Renaissance Movement’, MacDiarmid describes him as:

A scholar, a lover of all the arts, a great wit, a well-informed Scot with all his country’s best interests at heart and above all a passionate concern for freedom and hatred of every sort of cant or humbug, he typifies all that is best in the Scottish National Awakening now in progress and is contributing magnificently thereto.

The rest of the leaflet does not so much explain how a commitment to the Scottish Literary Renaissance will shape Smith’s rectorial work, as set the two strands of his campaign side-by-side, leaving the voter to trace a connection. For example, it gives the following ‘Four Reasons for Supporting Sydney Goodsir Smith’:

- His distinction is that of real creative genius.

- He would be sure to give a worthwhile and amusing address.

- He is a Scotsman who believes in his own country.

- He would be a real students’ rector.

In places, the leaflet is a little self-contradictory. Students are asked to vote for Smith because ‘a Scottish university should first of all honour the great men of its own country’. They should not vote for Fleming, however, because he may be ‘a great scientist and benefactor of mankind’ but the ‘rectorship is an office of spokesman for the student body, not an honour per se‘.

Perhaps, in fact, the strongest claim that emerges from the leaflet is the likelihood of Smith delivering a colourful rectorial address. His credentials as ‘wit and humorist’ are illustrated in a series of put-downs of rival candidates. Particularly acerbic barbs are directed at Jimmy Logan (‘information scanty but supposed to be a comedian’), politician Sir Andrew Murray (‘nicely groomed ex-provost … non-allergic to limelight’), Evelyn Waugh (‘hobby – writing blue books for naughty, naughty Catholics’), and the Aga Khan (‘but who can’t?’).

Since acquiring the leaflet, we have discovered that another recent purchase, the archives of the Edinburgh student literary magazine The Jabberwock (Coll-1611), contains a draft version of Smith’s ‘Message from the Candidate’, together with the original manuscripts of the endorsements by Hugh MacDiarmid and Edith Sitwell. The Jabberwock’s editor Ian Holroyd evidently worked as Smith’s campaign manager, and the archive also contains a letter from veteran Scottish writer Compton Mackenzie, regretting that he cannot endorse Smith’s candidature, as he has been approached by two other candidates with equal claims on his support.

The draft of Smith’s ‘Message from the Candidate’ contains a substantial amount of text omitted from the published version. One deleted paragraph reads:

If this were a political election (which I am told it is not to be, this time), I think my sentiments would be well-known to some of you as those of a man who wished to restore the ancient dignity of Scotland – all-out, in fact, and only falling somewhat short of bombs in letter-boxes and Customs at the Border. However, as this is not to be political, and as we are unfortunately unlikely as yet to get the chance of reducing the tax on whisky, I come to you with no ‘policy’ at all. I have none, in the circumstances, for I believe it would not be proper (in the happy event of my election) or my place to represent any other body than the students of this University and to be their spokesman on the University Court.

Was it the hints of political extremism, the allusion to Smith’s drinking habits, or the cheery admission of having no policy, that most alarmed Smith’s campaign manager? Also deleted is the postscript ‘I am truly sorry Groucho refused – he’d have unstuffed a few more shirts’. Groucho Marx had, in fact, been asked to stand as a rectorial candidate, but sadly declined.

In the end, Sir Alexander Fleming, who enjoyed the near unanimous support of medical students, won a resounding victory. Smith’s backers may over-estimated the average Edinburgh student’s interest in literature. Canvassers for Evelyn Waugh commonly met with the response: ‘Who’s she?’

For more on the 1951 Rectorial campaign, see Donald Wintergill, The Rectors of the University of Edinburgh 1859-2000 (Edinburgh: Dunedin Academic Press, 2005), pp. 127-35. Although Smith was never to stand again, his father Sir Sydney Smith won the next Rectorial election in 1954.

Paul Barnaby, Acquisition and Scottish Literary Collections Curator

UPDATE: Subsequent research in our C. M. Grieve Archive has revealed that Sydney Goodsir Smith was invited to stand for Rector by the university’s recently formed Scottish Renaissance Society. In a letter to Hugh MacDiarmid, dated 14 October 1951, Ian Holroyd writes that ‘we thought Sydney a very good choice as a Scottish literary candidate in that he can draw support from the medical faculty as son of the dean and a former student as well as appealing to the nationally-conscious Scottish undergraduates’ (MS 2951.6/6-7).

Victorian Veterinary Journals

Recently I worked on digitising a small number of volumes of The Veterinary Journal from the late 19th century and late 20th century. Almost 100 years apart, the earlier volumes from 1889-1898 had some questionable advice and cures for ailments including the free use of toxic chemicals and even a few drams of whisky for a horse’s stomach ache! We view these archaic methods nowadays with humour – after all, some absurdities are expected from a late Victorian medical journal.

Student interns in Stack III this summer

Over this summer, our three student interns, Thomas, Holly and Mila have been hard at work behind the scenes in New College Library’s Stack III. Their task was to work with the X Collection, a collection of large (folio) early printed books. Over the years this collection had gathered a layer of dust, which our interns carefully removed with a museum book hoover. Having our interns handling each of these books was also a great opportunity to learn more about them, and to understand how the collection was composed in terms of date, language and place of publication. These details were logged using methodology adapted from projects on collections in National Trust Houses.

Over this summer, our three student interns, Thomas, Holly and Mila have been hard at work behind the scenes in New College Library’s Stack III. Their task was to work with the X Collection, a collection of large (folio) early printed books. Over the years this collection had gathered a layer of dust, which our interns carefully removed with a museum book hoover. Having our interns handling each of these books was also a great opportunity to learn more about them, and to understand how the collection was composed in terms of date, language and place of publication. These details were logged using methodology adapted from projects on collections in National Trust Houses.

We’re delighted to say that that our interns have tackled three full bays of the X Collection, and cleaned and logged over 1600 books. We now know that the collection (as logged so far) is almost entirely pre-1800 in date, predominantly in English and Latin and pretty equally split between European and UK imprints. All this information will help us to develop future projects to catalogue this collection online.

It was a pleasure to work with our student interns, and through their enthusiasm to rediscover these collections. Hope to do it all again next year!

Christine Love-Rodgers, Academic Support Librarian – Divinity.

With thanks to Margaret Redpath, NCL Library Services Manager and Karen Bonthron, ECA/NCL Helpdesk Team Lead

Alexander Murray Drennan – pioneer of Eusol

Alexander Murray Drennan – or Murray to his friends – was born in Glasgow on 4th January 1884, and grew up in Helensburgh before coming to Edinburgh in 1901 to study medicine. Murray was a keen letter writer, and his letters to his sweetheart ‘Nan’ (Marion Galbraith, who would later become his wife) give an insight into the life of a young aspiring medical student:

Our first class begins at 8am so we have to be up betimes in the morning. From 8 to 10 I have anatomy and then at 11 I go over to the Infirmary; nominally we leave there at 1pm but on Operation days, twice a week at least, it is often 3 before I get away as I have the pleasure of being the instrument clerk and as such have to see after the instruments.

– GD9/45

It wasn’t all hard work, though. Murray’s letters to Nan and his family recount evenings spent at enjoying Edinburgh’s cultural offerings (“I went to see Faust on Monday night. It is rather a ‘creepy’ sort of opera but the music is very fine”); attending dinners (“at night there was a complimentary dinner given to Professor Beattie in the Caledonian Hotel … Beattie was very popular when he was here and no wonder for he was an exceptionally nice man and knew his work thoroughly”) and afternoons spent playing tennis and golf with fellow students as well as professors (“Professor Schӓfer had the goodness to ask me down to North Berwick to golf with him … a most enjoyable day’s golf in the most delightful weather. We went back to the house and had tea and then I had just time to get the 6.43 train back”).

Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh Residents, Summer 1907. Drennan is seated front row, far right.

After graduating MB ChB in 1906, Murray took up a practical apprenticeship as a Resident of the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh. In between visiting patients and supervising the various nurses, clerks, dressers and medical students who attended the wards, the Residents made time to enjoy themselves (you can find out more about their antics over on the LHSA blog). In one letter to Nan, Murray related a night out for the ‘Mess’:

RIE Residents on a bus, ready for an outing.

Friday … evening at 9pm, the Mess having chartered a visitor bus (& driver) set out for Peebles. It created quite a sensation when at the appointed time one of these large buses labelled “Jeffery’s Lager” rolled up to the door & we all embarked. The inside was converted into smoking room, saloon bar, while the upper deck was occupied by the sightseers. It was very funny going out Dalkeith Rd, several people tried to get on board thinking it was a public conveyance, needless to say their attempts to mount our machine were not encouraged by word or deed. The run out was delightful as it was a clear warm evening & the road lies through pretty country. We got to Peebles shortly after 11pm & found supper all ready for us at the ‘Cross Keys’ inn. As usual the Mess meeting was constituted & we did full justice to the repast, reembarking again about 12.40am.”

– GD9/46

Following his residency Murray stayed close to home, working in the by-now familiar Pathology Department of the University of Edinburgh. When war broke out in 1914, he signed up as an official Pathologist with the Royal Army Medical Corps (R.A.M.C), and in 1915 he had to postpone an imminent appointment as the first full-time Professor of Pathology at the University of Otago in New Zealand and instead make his way to the R.A.M.C. Depot in Aldershot. In a letter home dated October 1915, he describes some of the men he will serving with and the set-up of their team:

The staff seem all very decent men, one or two are well over forty & must have been in practice. There are several Edinburgh graduates amongst them … on the whole I think we should work well together … There are two or three surgical specialists, one medical specialist, several radiologists, several anaesthetists and one bacteriologist … there is a little man Brown who has done a little in that way & I shall try & get him on to help, but he does not profess much technical knowledge!

– GD9/7

In early November 1915 Murray’s unit was deployed to Mudros, on the island of Greece. He would later describe how this previously “bare, stony island” was overtaken by military personnel:

As the occupation spread the whole of the harbour side of the island was dotted with tents from Mudros East to Condia on the west. It was a shifting population, today 10000, next week perhaps 60000. The only permanent fixtures, so to speak, being the various H.Q.s, the Base depots and the Hospitals.

To the north a little outside Mudros East were several stationary hospitals situated on a sun-baked flat, and there they bore the burden of the day; blinded with dust and flies and crowded up with cases of dysentery, the staff often sick, they cheerily toiled along. In the neighbourhood also were numerous camps of combatant units; and one bright spot, facetiously known as the “dogs’ home”, where extra medical officers were kept on the chain and supplied as required to the Peninsula or to units on the island.

– GD9/38

Murray’s letters home to Nan and their children from this time paint rather a relaxed picture of life in war time. Reading them, one is left with the impression that he only wanted to recount activities that his wife would be familiar with, rather than the full realities of a life in an overseas field hospital. One letter, for example, describes how they spend their evenings: “After dinner we had our usual games at whist. It is quite an institution and we have played every evening after dinner, always Richards and Thuilliers against the Colonel and me, and so far the games have been very even”. In another letter, Murray talks of attending a garden party: “it was just quiet tea in the Fergusons’ little garden, a shady spot with palms, & bougainvillea, & such things growing about. … We had tea & chatted & then left in small batches”.

Alexander Murray Drennan in Cairo, 1915

By 1915 some of Murray correspondents had already been stationed abroad for some time, and his incoming letters give insights into some very different military experiences. Murray’s younger brother James Stewart Drennan (who had joined the Royal Horse and Field Artillery in 1912) described life in Salonika and a close encounter with a German zeppelin:

It has been beastly hot here again the last few days and we have now chucked working in the middle of the day, instead we lie on our beds in a more or less nude condition and curse the flies, luckily it is still nice and cool at night.

Salonica [sic] had another visit from a Zepp. three or four days ago, just before daylight. All the guns and searchlights in the place got on to it at once and it was brought down before it had a chance of dropping any bombs. It came down in the marshes at the mouth of the Vardar River and the men were captured, so were felt rather bucked at having bagged a Zepp in this corner of the world.

– GD9/10

A letter from Tom Graham Brown, physiologist and mountaineer, gives an insight into the life of medical personnel at home:

Write me a decent letter and tell me all your news. I wish I was out there with you. I am at present fixed in this hospital which is one for shock cases – mostly men who are pretty badly shaken or bad mentally after bombardments. Very many of them get well – tho’ we get a good many early G.P.I’s before they are diagnosed.

I wish all the same that I could get out. It isn’t any catch being in this country. However I must trust to luck.

– GD9/4

Yet another perspective was provided by Dr John Fraser (later Prof. Sir John Fraser, Principal of University of Edinburgh). Dr Fraser was stationed in Northern France, and his letters describe the long, difficult days the staff there endured:

Lately we have been deluged with work: you can probably imagine what Monday was like. I was in the theatre from 10am to 12 midnight, and in that time there were 6 craniotomies: an amputation and 2 gas gangrene: in addition to others. One doesn’t feel much inclined for reading or writing after such days.

– GD9/100

There were benefits to working in such tough conditions, however. War often brings about significant advances in technology and medicine: as well as the greater incentive to improve the health of fighting forces, the need to take risks and experiment can also increase.

Many of the battles of WW1 took place on muddy farmland, and it could sometimes be days before a soldier was transported to a clearing hospital for comprehensive treatment. This meant the risk of already-traumatic wounds becoming infected was high, with gangrene claiming many lives.

For some time prior to his deployment Murray had been working with colleagues in the Pathology Department at the University of Edinburgh “to find an antiseptic which could be applied as a first dressing in the field to prevent sepsis”[1], and in 1915 they published a paper in the British Medical Journal on their experiments with ‘Eusol’, or Edinburgh University Solution of Lime. This was a combination of bleaching powder and boric acid, and early experiments both in the wards and in the field showed great success at reducing infection and speeding up healing.

In gathering accounts of these experiments, Murray relied on other colleagues who were using the Eusol treatment. This letter from Dr Fraser sets out the dilemma faced by many front-line surgeons, and his experience using Eusol:

Since I last wrote you I have had a run of gas gangrene cases, all of them I have treated with Eusol and in each case I have been thoroughly satisfied with the result. With one case I was exceedingly impressed. Lt. Col. —- had been infected 5 days before admission to the Hospital – on admission there was most gangrene to the lower of the knee: from this knee to the groin there was the gas infection of the tissues which precedes the tissue necrosis. One was faced with three possibilities – 1. Leaving him alone to die 2. Doing a flapless amputation at the hip joint: a mutilating operation from which few recover 3. Amputation through the centre of the thigh, in other words, through the centre of the gas infected area, and risking it.

I chose the last: I did the operation under Special Anaesthesia and as I was doing the operation I remarked that it ought to satisfy the criteria as regards the use of Eusol. I amputated through the thigh and not only so but I made flaps and partly closed the wound, a thing one had never dared to attempt previously… The result was a complete success: no trace of gangrene appeared subsequently.

– GD9/100

A further hurdle to be overcome in wartime was the difficulty in communicating such advances. Recognising the delays to the mail that could occur, Murray devised a system for himself and Nan:

I sent off my last to you on Sunday afternoon, & I labelled it no.1 as I explained so that you would know by the number if a letter was missing, of course I have sent several to you before I began the numbering. This is a recapitulation in case you didn’t get my last letter.

– GD9/4

Murray also kept a small diary in which he recorded letters sent and received – an absolute dream for archivists and researchers!

There are roughly 6 archive boxes of letters like this – thankfully Drennan had a system by which to organise them!

No such system was in place for the medical men, however, and correspondence over a number of weeks between Murray, J. Lorrain Smith and Fraser details the somewhat arduous process of getting an article published.

I am sorry to have been so lazy in getting this note away, but during the last week the pace of work has increased and although [things are quieter] at present, if I do not get these away now it may be a long while before I have another opportunity.

– Fraser to Drennan, 17 Sep 1915

For the past fortnight I have been cut off from all correspondence and your letter and the manuscript were awaiting me here on my return. I have handed the manuscript to the Colonel and he has approved of it: he forwards it to the DMS [Director of Medical Services] and who if he approves will forward to the War Office: the WO will notify the BMJ or Dr Fletcher to proceed with the publication. The ways of the army are wonderful but there they are!

– Fraser to Drennan, 5 Dec 1915

By 1916 Eusol was an established means for treating septic wounds, and even today[1] hypochlorus acid forms a backbone to attempts to accelerate wound healing.

After being discharged from service in 1916, Murray was finally able to take up his place in New Zealand, with his wife and children joining him shortly after. They remained there until 1929 when Professor Drennan took up the Chair of Pathology at Queen’s University in Belfast, and in 1932 he returned to his alma mater to take up the Chair at the University of Edinburgh, where he remained until his retirement in 1954. Professor Drennan died in 1984, a few weeks after his 100th birthday.

Alexander Murray Drennan and family on a picnic in Dunedin, New Zealand.

References

[1] http://www.pmfanews.com/media/4762/pmfaas17-cleansing-new.pdf

[1] 2 Smith JL, Drennan AM, Rettie T, Campbell W. Experimental observations on the antiseptic action of hypochlorous acid and its application to wound treatment. BMJ 1915;ii: 129-36.

New College Library Collections go under wraps during essential maintenance work

Essential maintenance work is being undertaken in September and October on the New College heating system. We will be installing protective coverings in the Library to manage risks of leaks from the heating pipes which run through the New College Library collections on all the Stack floors. This means that public access to library collections in Stack I and Stack II is likely to be restricted between Monday 28 August and Wednesday 20 September. The Library Hall and the David Welsh Reading Room will be open as usual, and we will be running a fetch on demand service for library users with hourly collections. We regret that there is likely to be some noise disruption from the works during September and October, and we will continue to provide earplugs for anyone who needs them.

Updates and further information on New College Library

Christine Love-Rodgers, Academic Support Librarian – Divinity

Collections

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Projects

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....