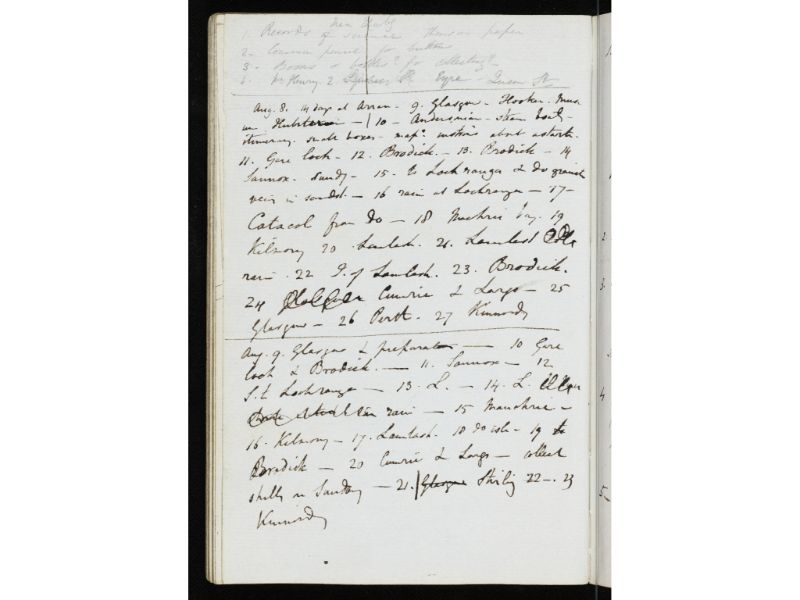

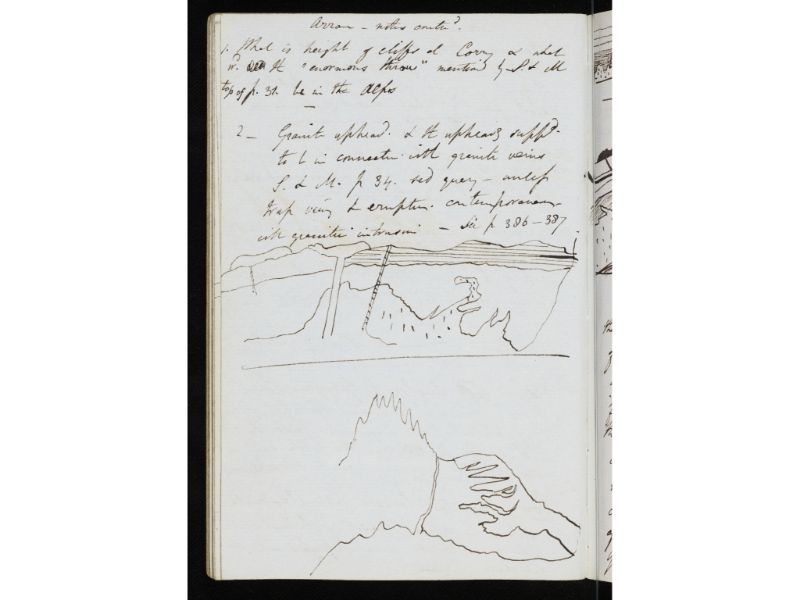

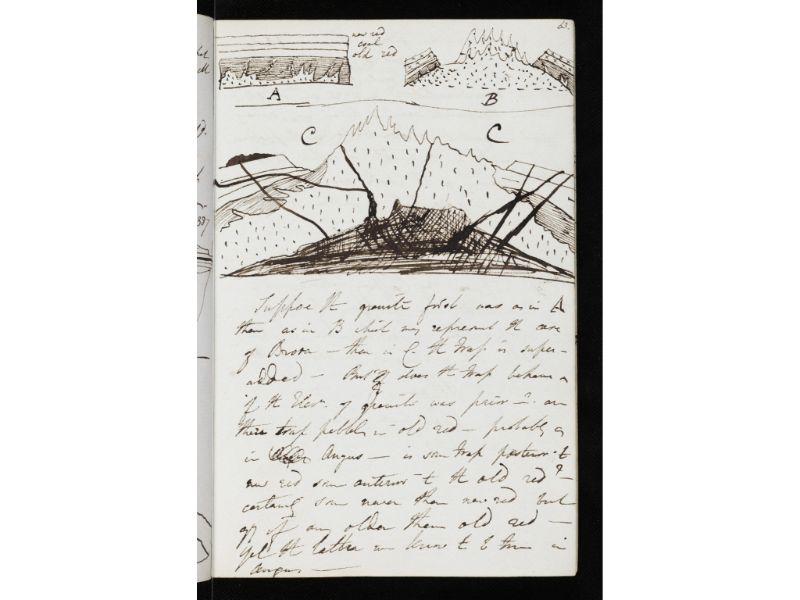

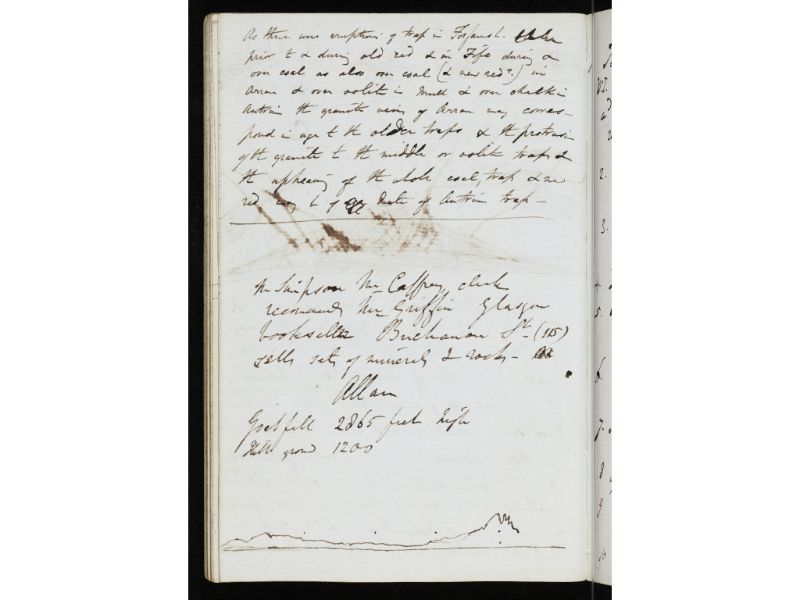

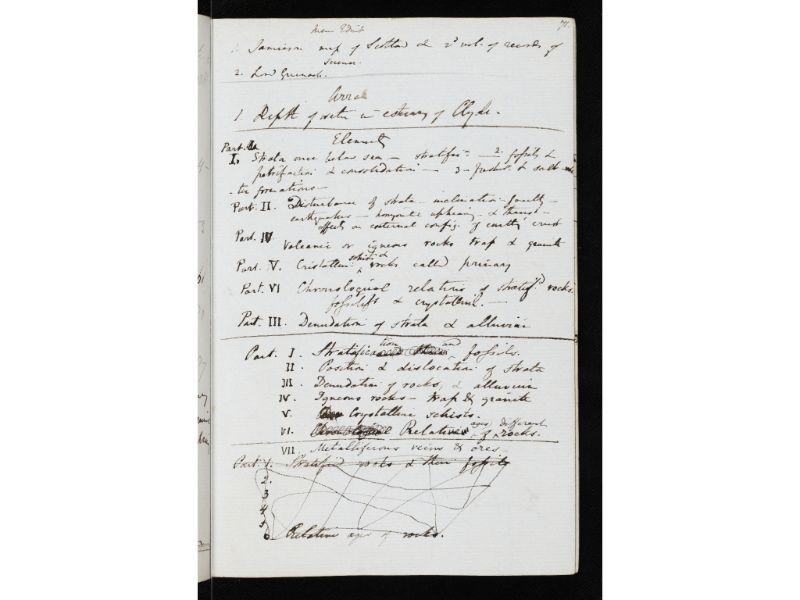

‘No. 1 Mem for Tours’ features ‘Author’s (CL’s) Copies of Papers’.

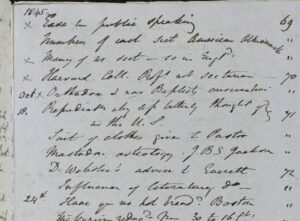

In his Scientific Notebook 1, dated March – April 1825, Charles Lyell lists things to take on his first geological tour, designed to gather the evidence for his first book. In the list, he notes ‘Author’s (C.Ls) copies of papers‘, and it’s delightful to see him describe himself in that role.

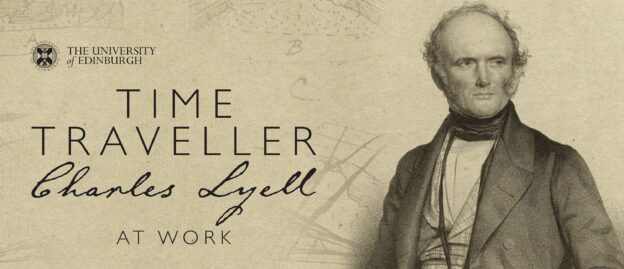

Felicity with Jeremy Upton, Director of Library & University Collections at Lyell exhibition opening.

Felicity MacKenzie came across Charles Lyell whilst completing her History degree at Bristol – and for a considerable part of that, consulted online versions of his books during lockdown conditions. Felicity has now completed her Masters degree at Cambridge, where again, she was able to focus on Lyell. She is currently applying for a PhD in order to be able to explore his life further. Here, she gives a thorough introduction to Lyell’s books, as well as current links to online versions.

The books that Charles Lyell wrote played an important role in the way in which he honed and communicated his geological work. When considered alongside each other, they offer the opportunity to trace the threads that run across Lyell’s thought and practice, as well as to compare and contrast his interests and concerns at different times in his career.

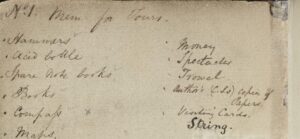

A selection of different editions of Lyell’s Principles, held at the University Library.

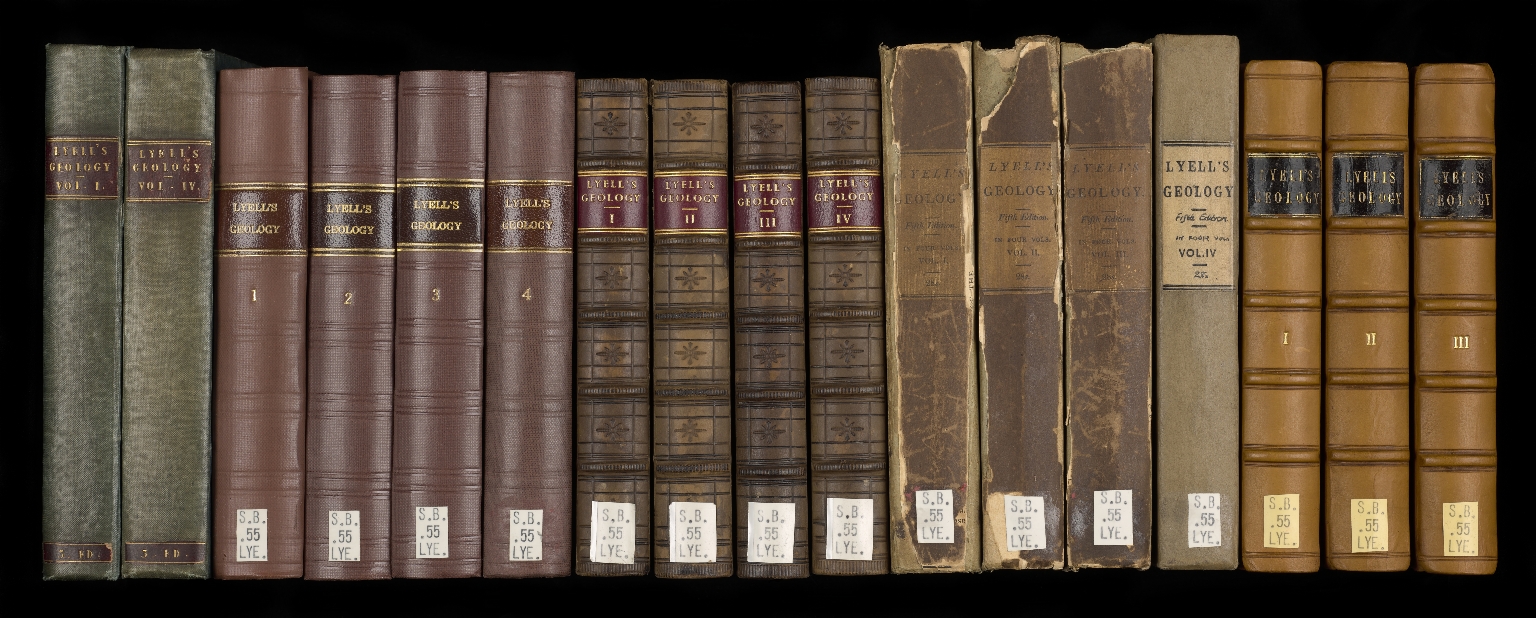

Lyell’s first and most famous book was the Principles of Geology: Being an Attempt to Explain the Former Changes of the Earth’s Surface, by Reference to Causes Now in Operation. Initially published in three volumes – volume I 1830, volume II 1832 and Volume III 1833, the Principles was reprinted in twelve editions over Lyell’s lifetime and sold over twenty-five thousand copies. As the name suggests, Lyell used the book to consolidate and promote the ‘principles’ by which he believed modern geological science should be conducted. The most central of these principles was Lyell’s insistence on the exclusive explanatory authority of the reliable, rationally trained human observer.

For Lyell, human witness and reason formed the only basis for truth. This led him to state his

famous case – that ‘the present is the key to the past’ based on the idea that the action of

geological causes in the present, fell within the remit of human observation, and so formed the only trustworthy basis for knowledge about the way in which such forces might have acted in the past.

Principles, 10th Edition, volume 2, 1868.

This kind of human reason-centred geology had particular political ramifications in the 1830s, when ideas about reason versus revelation – and the bearing of the Bible upon truth – had significant implications for the politics of church, state and education. Lyell was aware that his work could produce heated debate and touch realms beyond geology. As a result, he structured his rhetoric in the Principles carefully. In so doing, he produced a masterpiece in the tactful presentation of controversial ideas. The Principles burst onto the British intellectual scene and remained an important cultural work throughout the nineteenth century and beyond.

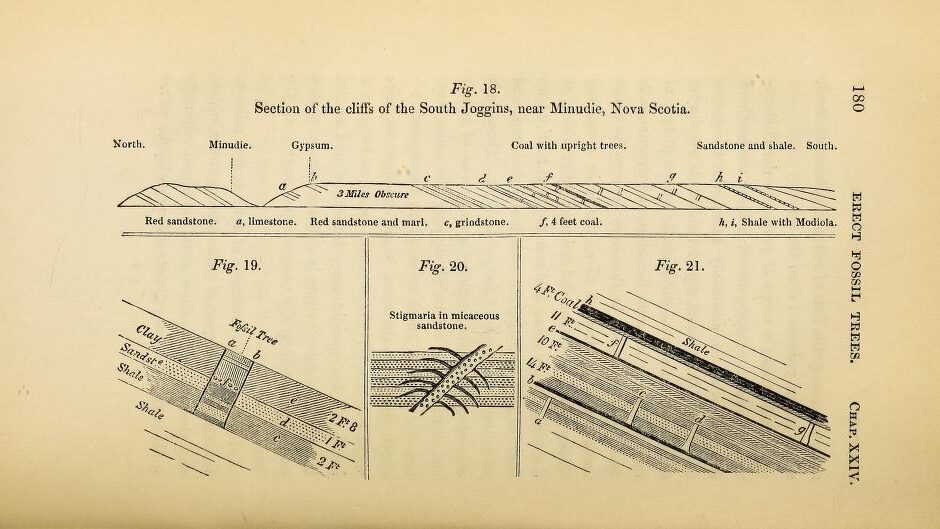

Lyell’s second book was the Elements of Geology (1838). This was published in seven editions

between 1838 and 1871; its name changing to the Manual of Elementary Geology with the third

edition. This book was a practical, ‘how-to’ supplement to much of the material already covered

in the Principles, and taught the practitioner what they needed to know for application in the

field.

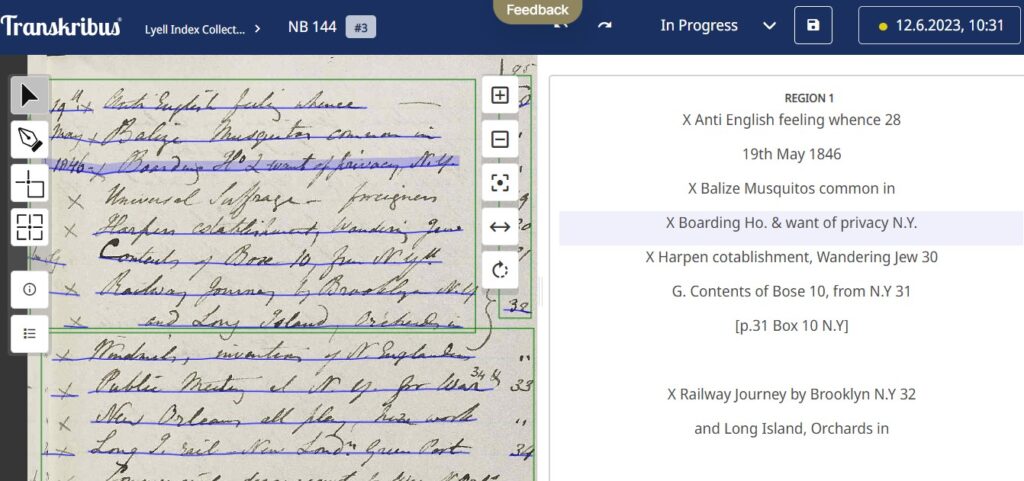

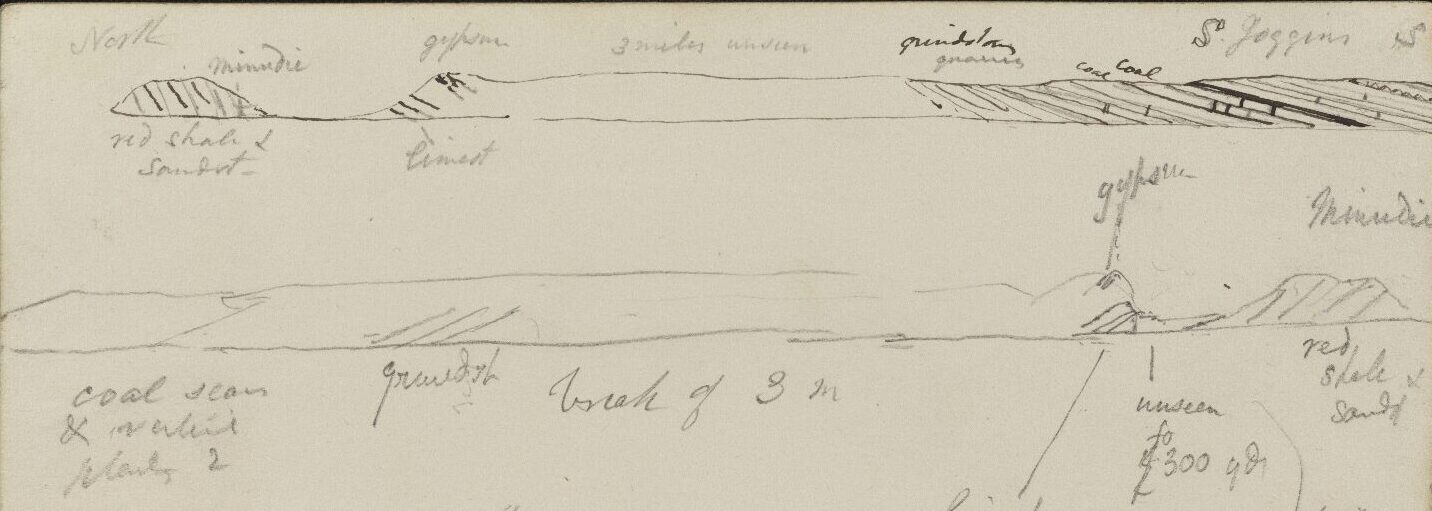

Next, came Lyell’s American travelogues. Lyell was invited to give a series of lectures at the Lowell Institute in Boston in 1841. During this visit, Lyell not only lectured in Boston, Philadelphia and New York, but travelled extensively around the northern and southern states with his wife Mary, observing and collecting geological phenomena. On returning home, Lyell decided to write up his geological work alongside social and political commentary. This resulted in the Travels in America: With Geological Observations on the United States, Canada, and Nova Scotia volume I and volume II in 1845.

Next, came Lyell’s American travelogues. Lyell was invited to give a series of lectures at the Lowell Institute in Boston in 1841. During this visit, Lyell not only lectured in Boston, Philadelphia and New York, but travelled extensively around the northern and southern states with his wife Mary, observing and collecting geological phenomena. On returning home, Lyell decided to write up his geological work alongside social and political commentary. This resulted in the Travels in America: With Geological Observations on the United States, Canada, and Nova Scotia volume I and volume II in 1845.

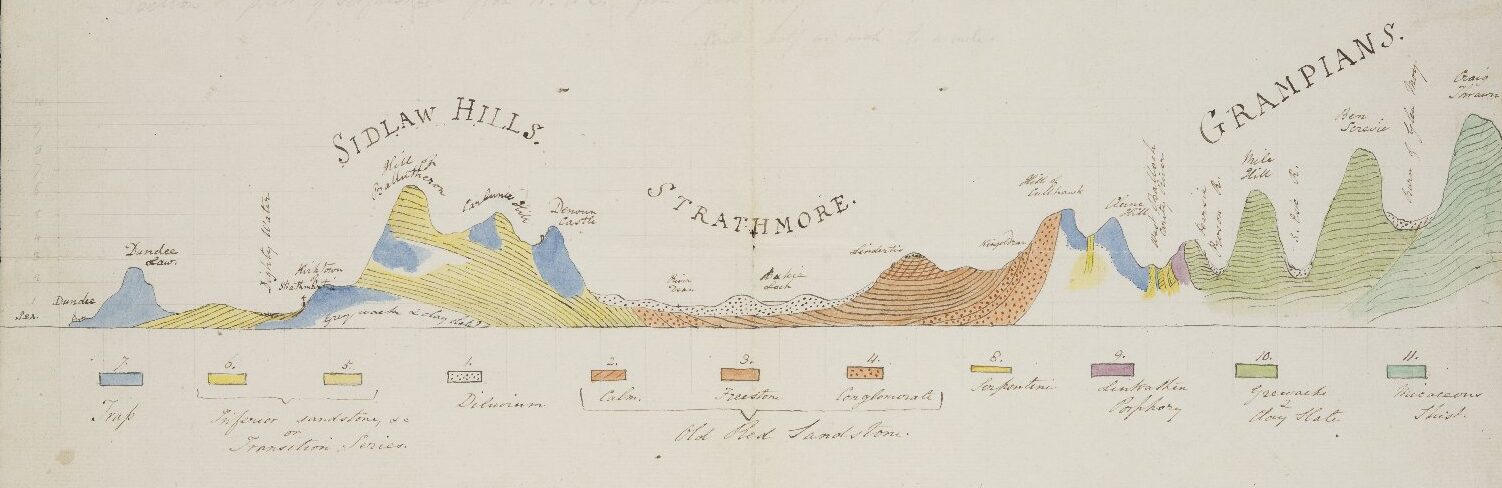

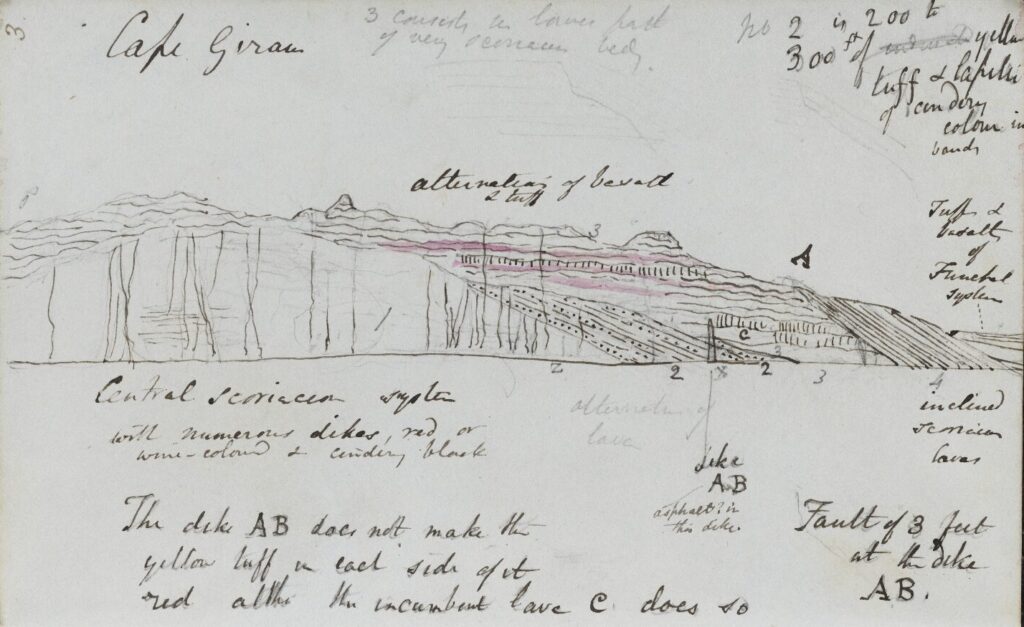

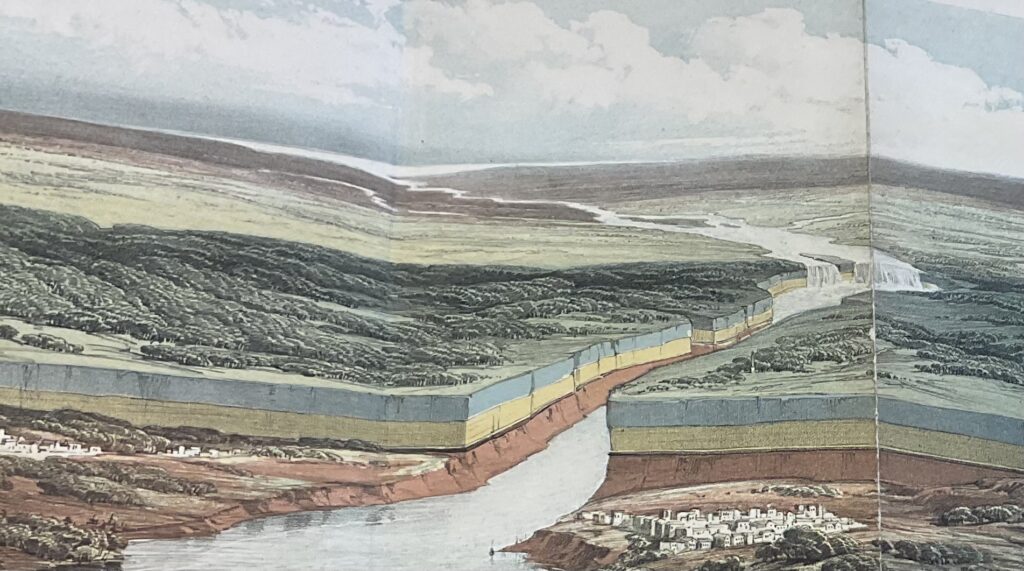

Both volumes include terrific foldouts, necessary to accommodate the scale of the country and its geological features.

Illustrations were important to Lyell, and in his Travels he included a fantastic fold-out, necessary to accommodate the scale of Niagara

That same year, Lyell was invited to lecture again at the Lowell Institute, and factored in another nine-month stint of travelling. The results were published in his A Second Visit to the United States of North America volume I and volume II, in 1849. Once again, a significant portion of this work was dedicated to social and political commentary, which makes it an important insight into Lyell’s broader ideology. In particular, it sheds light on Lyell’s very problematic attitude to race and enslavement

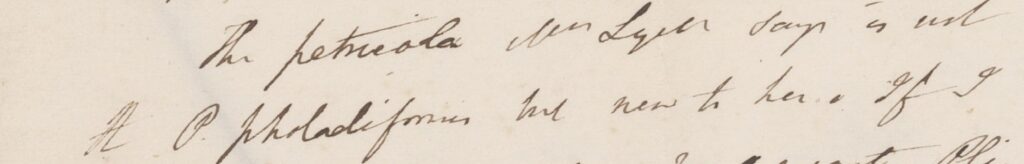

Lyell’s final book was the Geological Evidences of the Antiquity of Man, with remarks on theories of The Origin of Species by Variation (1863). This work focussed on the question of human antiquity and is famous for how many people Lyell upset with it. Charles Darwin was frustrated that Lyell did not take the opportunity – as a significant figure in the highest echelons of British science – to offer full support for an evolutionary account of human origins. Additionally, Lyell infuriated colleagues, such as Robert Owen, Hugh Falconer and John Lubbock, who accused him of plagiarising their own and others’ works.

Lyell’s final book was the Geological Evidences of the Antiquity of Man, with remarks on theories of The Origin of Species by Variation (1863). This work focussed on the question of human antiquity and is famous for how many people Lyell upset with it. Charles Darwin was frustrated that Lyell did not take the opportunity – as a significant figure in the highest echelons of British science – to offer full support for an evolutionary account of human origins. Additionally, Lyell infuriated colleagues, such as Robert Owen, Hugh Falconer and John Lubbock, who accused him of plagiarising their own and others’ works.

Each of Lyell’s books had a different and important impact on the intellectual and cultural life of nineteenth-century Britain. Hugely successful, they chart a course over what was an amazing timeframe in both scientific findings and their popularisation.

Thank you Felicity for sharing your knowledge on Lyell’s books with us! Copies of Lyell’s books from the University’s collections, as well as Lyell’s own annotated copies, are featured in our current exhibition. We will be featuring Felicity’s comprehensive online book list, and more, in our forthcoming website.

Recommended further reading:

- James A. Secord, ‘Introduction’, in Principles of Geology (London; New York: Penguin Books, 1997)

- Martin J.S. Rudwick, Worlds before Adam: the reconstruction of geohistory in the age of reform, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008)

- Martin J.S. Rudwick, ‘The Strategy of Lyell’s Principles of Geology’, ISIS, 61:1 (1970), 4-33

- Roy Porter, ‘‘Charles Lyell and the Principles of the History of Geology’, The British Journal for the History of Science, 9:2 (1975), 91-103

- Stuart A. Baldwin, ’Charles Lyell: A Brief Bibliography’, (Essex: Baldwin’s Scientific Books, 2013)

- Robert H. Dott, Jr., ’Lyell in America: his lectures, field work and mutual influences 1841-1853’ Earth Sciences History, 15 (1996), 101-140

- W. F. Bynum, Charles Lyell’s ‘Antiquity of Man’ and Its Critics, Journal of the History of Biology, Summer, 1984, Vol. 17, No. 2 (Summer, 1984), pp. 153-187