This month we learn that Erin, one of our Lyell project volunteers, has had her eyes opened to the present-day natural world – thanks to inspiration from our Sir Charles Lyell Collection.

We have all caught the Lyell / Geology bug here at the Sir Charles Lyell Collection Project HQ. Each of us has developed a preoccupation with spotting and identifying pebbles, fossils, gneiss, and schist and so on. Our work and personal libraries groaning with the additional weight of multiple biographies of Lyell, and an almost absurd array of spotters guides to rocks, minerals and fossils. Even our twitter feeds are increasingly populated with evidence of geological time lines (mostly pebbles with veins). No return from a trip to the beach complete without a pocketful of geological specimens; pebbles of grey granite, ovoid pebbles of slate with quartz vein running through it, fragments of whitish chert, and things we used to know, simply, as shells.

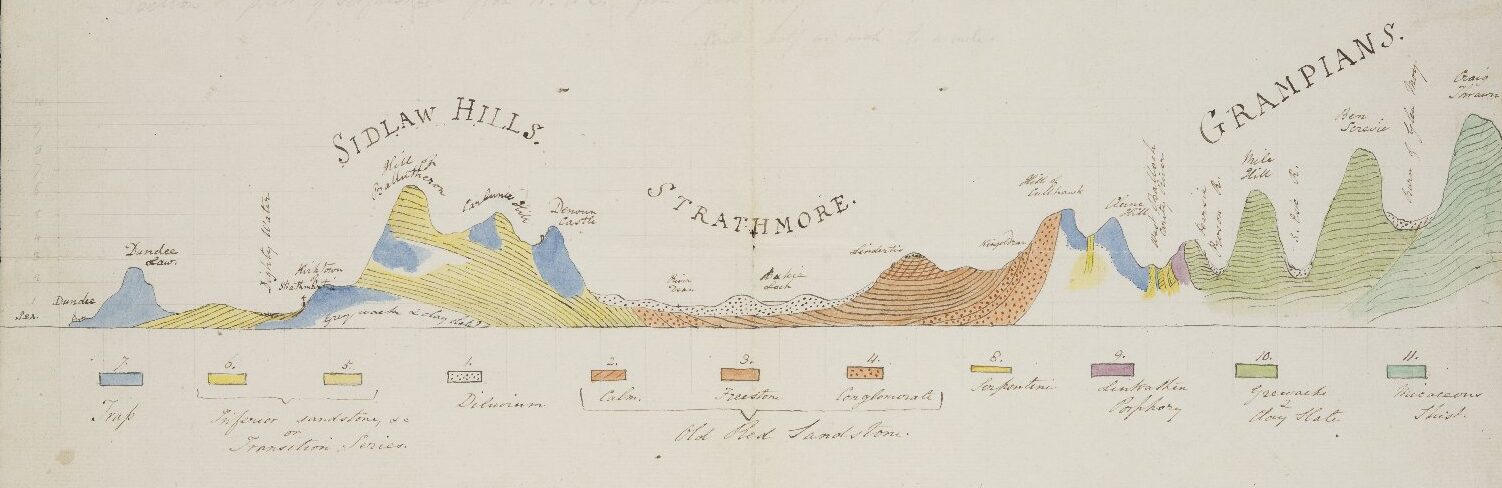

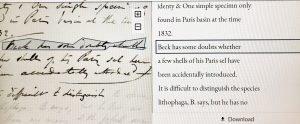

A list of shells sent to Bedford Place, dated 5 February 1840, from Sir Charles Lyell’s Notebook, No. 80, 5 February 1840 – 25 June, 1840, (Ref: Coll-203/A1/80)

On my desk, as I type, are an assortment of granite, quartzite, and possibly metamorphic mud – a recent haul from Point beach on the Isle of Lismore. It is one of the great privileges of working so intimately with historical collections: we are repeatedly offered a unique opportunity to develop knowledge and interest in a person, subject, or era that, most likely, would have eluded us had we chosen a different line of work. Earlier this week I read, in the New York Times, Dennis Overbye’s review of the renovated hall of gems and minerals at the American Museum of Natural History. He suggests that ‘Geology Is Our Destiny’.1 For all of us working together to interpret, catalogue and make accessible the Sir Charles Lyell Collection, it would certainly seem so.

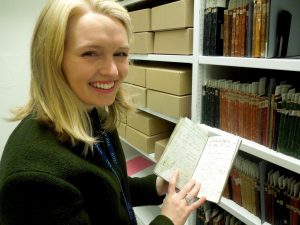

Project volunteer, Erin, has developed only a little infatuation with molluscs (to the extent that her new found knowledge required the creation of its very own data-set – Erin is a qualified archivist after all). In working with the Lyell notebooks, Erin has begun to see the world through Lyell’s nineteenth-century geological wisdom. The present-day natural world has opened up to Erin in a way she had never imagined possible. Here, Erin tells us more about her work transcribing Lyell’s notebook indexes and how it has fuelled her growing obsession.

“Transcribing Sir Charles Lyell’s scientific notebook indexes has been a sometimes ruffling but always captivating journey. The one thing I never expected was that like Lyell, I found myself becoming fascinated with molluscs. The Mollusca phylum is:

“one of the most diverse groups of animals on the planet, with at least 50,000 living species (and more likely around 200,000) [and it] includes such familiar organisms as snails, octopuses, squid, clams, scallops, oysters, and chitons”.2

Lyell often took note of the different genera and species he found during his travels. In notebook 80, for instance, I found a list of shells belonging to various molluscs which Lyell had identified and had sent to his home in London.

I felt like both an amateur detective and biologist as I hunted for these bivalves and gastropods on the World Register of Marine Species and MolluscaBase (a global species database, covering all marine, freshwater and terrestrial molluscs, both recent and fossil). As I transcribed, I felt compelled to document them and my new found knowledge about them in an Excel data-set. Some of them proved very elusive and some others are still a mystery. The excitement I felt each time I was able to find a mollusc Lyell had listed was extremely gratifying, particularly when the name he had recorded had fallen out of accepted or general use.

What I have loved most about transcribing Lyell’s notebook indexes is how much I am able to learn from only one index entry; nineteen molluscs in a single page that I had the pleasure of trying to find and learn about! This is what I feel is the most rewarding part of being an archivist. Through this amazing collection we are given the opportunity to explore the life and times of Sir Charles Lyell while presenting his knowledge, research, ideas and wondrous curiosity to a wider audience.

Now, each time I go to Yellowcraigs or North Berwick for a wild swim, I can’t help but stop and examine the rocks, the shells, the crab skeletons, the little pools full of marine life and of course the molluscs. I never would have stopped to explore in this way had I not first discovered so much through the eyes of Sir Charles Lyell.”

- North Berwick, a favourite swim spot and mollusc hunting ground for Lyell project volunteer, Erin. © Erin McRae

- One of Lyell project volunteer Erin’s present-day crustacean finds, a crab skeleton © Erin McRae

We hope you enjoyed reading about how the Sir Charles Lyell Collection has inspired our project volunteer, Erin, to observe and learn about her natural surroundings with new-found enthusiasm. Erin’s story is just one example of the power of historical collections to enable, support and enhance the acquisition of new knowledge, learning and understanding. We would love to know how you might use the collection to aid learning, teaching and research. Please share your thoughts in the comments.

Thanks to Dr. Gillian McCay, assistant curator at the Cockburn Geological Museum, for her help in identifying the Point beach pebbles. Look out for our next blog post, (coming very soon), when we will be taking a bit of a deep-dive into Lyell’s indexes and hearing from another of our project volunteers, Michael. Thanks for reading!

Elaine MacGillivray, Senior Lyell Archivist

Erin McRae, Lyell Project Volunteer

Sources and further information:

1. Dennis Overbye, ‘Why Geology Is Our Destiny’, The New York Times, 22 June 2021 (https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/22/science/natural-history-museum-gems-minerals.html), [accessed 25 June 2021].

2. Paul Bunje, ‘Lophotrochozoa: The Mollusca: Sea slugs, squid, snails, and scallops,’ Proceedings of the Royal Society B274(1624):2413-2419 (https://ucmp.berkeley.edu/taxa/inverts/mollusca/mollusca.php), [accessed 25 June 2021] .

World Register of Marine Species

MulluscaBase