“[Charles Lyell’s] cultivated mind and classical taste, his keen interest in the world of politics and in the social progress and education of his country, and the many opportunities he enjoyed of friendly intercourse with the most leading characters of his age, make the letters abound in lively anecdotes and pictures of society, constantly interspersed with his enthusiastic devotion to Natural History.” -Katherine Lyell, Life, Letters and Journals of Sir Charles Lyell, Bart, 1881

To mark 7 months working with the Lyell collection, I’d like to share some discoveries I’ve made while cataloguing these amazing notebooks, and researching Lyell’s published works. Lyell today is known for his great discoveries of the Earth, and the elevation and establishment of the science. Here, we see Lyell’s other interests.

Discoveries:

- Charles Lyell was deeply interested in the role of universities and education in society. He writes in his notebooks extensively about the religious requirements at Oxford and Cambridge, to which he objected. In Notebook 4 he makes this list:

![An image of a notebook page written in pencil or light pen in which Charles Lyell writes his thoughts on University education. Transcript: What is the portion of those who ought to have a Univ[ersit]y Ed[ucatio]n in England. Who really have one? 1. Learn number Att[ourn]ys & their cle-rks. Barristers not Oxf[or]d or any Univ[ersit]y men - Dissenter who an barrister, attournies, or spe-cial pleaders &c [etc] 2. Engineers, Architects, Surveyors 3. Physician dissenters how many Surgeon d[itt]o. Discipline was intended. ought not those below 16 to be required to go to church.](http://libraryblogs.is.ed.ac.uk/lyell/files/2020/09/0183475c.jpg)

Notebook No 4, p. 106, one instance of Lyell’s notes on Universities and education.

Transcription: “What is the portion of those who ought to have a Univ[ersit]y Ed[ucatio]n in England. Who really have one? 1. Learn number Att[ourn]ys & their cle-rks. Barristers not Oxf[or]d or any Univ[ersit]y men – Dissenters who an barrister, attournies, or spe-cial pleaders &c [etc] 2. Engineers, Architects, Surveyors 3. Physician dissenters how many Surgeon d[itt]o. Discipline was intended. ought not those below 16, to be required to go to church.”

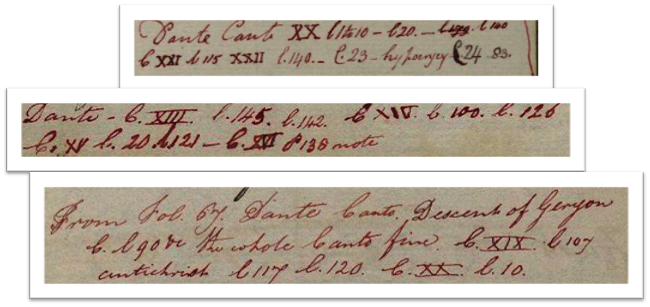

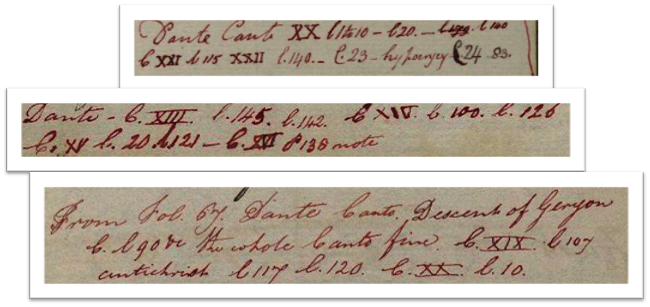

2. Dante’s Inferno was a constant reference in Lyell’s notebooks, though it’s not clear yet for what purpose, other than the geologist’s keen interest. In the midst of notes on other subjects, Lyell often makes brief abbreviated citations of the parts and lines of Dante. These must have been important to him, because he regularly references these citations in his table of contents. His father being a Dante scholar, this is intriguing for further research to understand how Dante’s poetry influenced Lyell’s understanding of the earth.

Excerpts from Notebook No. 4 (1827), where Lyell cites Dante.

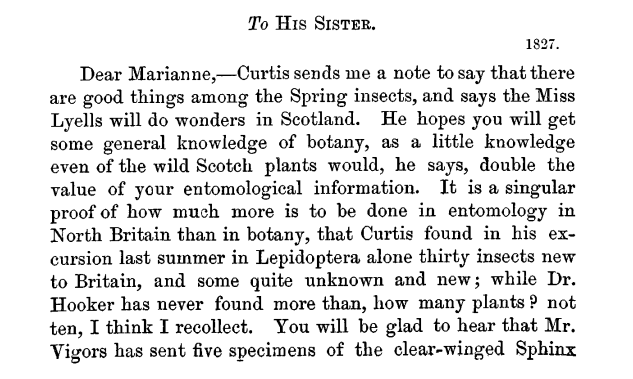

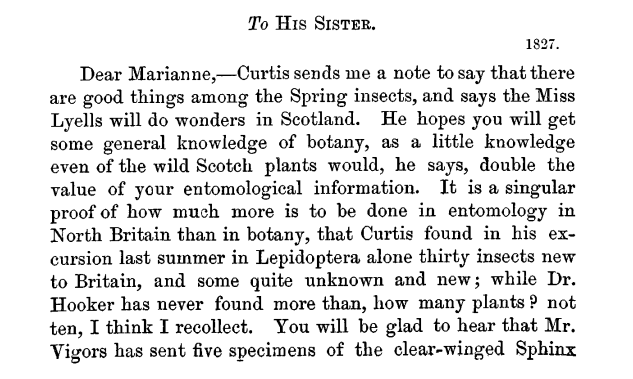

3. Lyell wasn’t the only naturalist in his family, his sisters and father were keen on insect collecting and naming. In those days, much of the flora and fauna of Scotland had no official name, and therefore budding lepidopterists “discovered” and named the insects they caught. We hope to describe illuminating family letters like this in the newly acquired papers of Lyell.

Letter to Marianne from Charles Lyell concerning the Lyell sisters’ prowess and interest in identifying insects

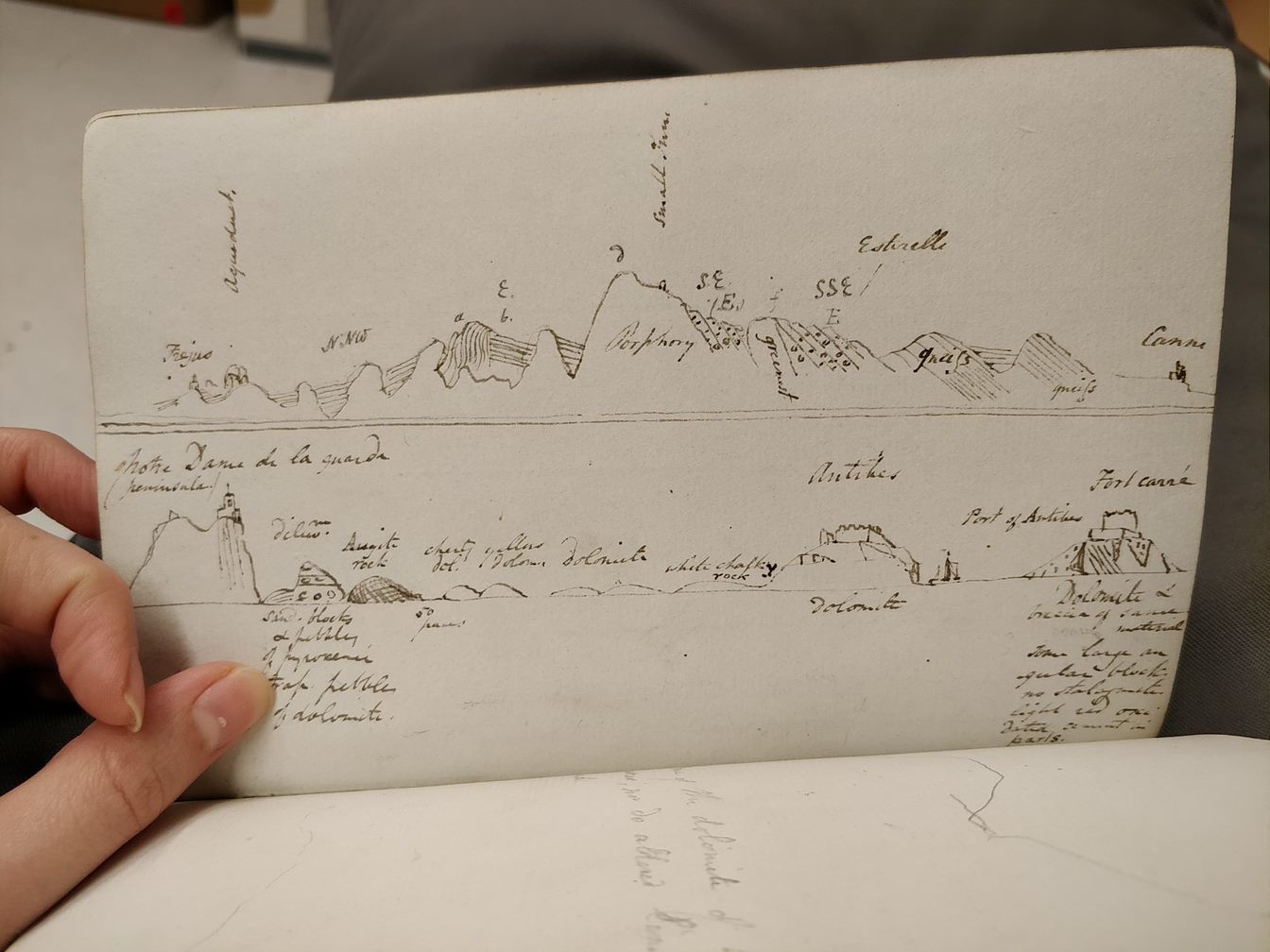

4. Lyell’s eyesight is known for being poor and limiting his abilities all his life, but the reason why is now contested. Most biographies cite that his eyesight worsened while studying the law by candlelight, but in a letter to Murchison in preparation for their Grand Tour to France and Italy, Lyell writes that his eye injury was caused by the long days in the Tuscan sun on holiday with his family. On that Grand Tour, to appease his father, Lyell brought with him a clerk named Hall to aid him in his work and treatment of his eyes – though no detail of the treatment has yet been found.

Excerpt from a letter to Murchison, April 29, 1828, explaining his father’s wishes for Lyell to bring his clerk with him, to make up for his troubles with his eyes.

References:

Lyell, C. (2010). Life, Letters and Journals of Sir Charles Lyell, Bart (Cambridge Library Collection – Earth Science) (K. Lyell, Ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511719691

Bailey, E., 1962. Charles Lyell, F.R.S., (1797-1875). Edinburgh: Thomas Nelson and Sons Ltd.

Charles Lyell Notebook No. 4, digitised here: https://images.is.ed.ac.uk/luna/servlet/s/cennww

![An image of a notebook page written in pencil or light pen in which Charles Lyell writes his thoughts on University education. Transcript: What is the portion of those who ought to have a Univ[ersit]y Ed[ucatio]n in England. Who really have one? 1. Learn number Att[ourn]ys & their cle-rks. Barristers not Oxf[or]d or any Univ[ersit]y men - Dissenter who an barrister, attournies, or spe-cial pleaders &c [etc] 2. Engineers, Architects, Surveyors 3. Physician dissenters how many Surgeon d[itt]o. Discipline was intended. ought not those below 16 to be required to go to church.](http://libraryblogs.is.ed.ac.uk/lyell/files/2020/09/0183475c.jpg)