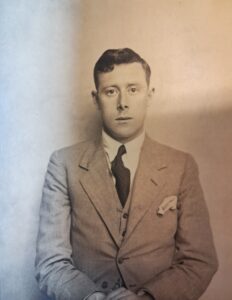

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for the last 4 months, I have been a Digital Collections Assistant working on digitising and improving information available regarding the Hill and Adamson Collection. Although my own research does not deal with conservation or Scottish heritage, I have a lot of experience working with archives and archival documents. Further, as my research area is based in East Asia, many of the documents I need are stored in archives that would require a long and expensive flight, thus the power of digitisation in conservation is very valuable to me personally as it allows me access to vital documents. Therefore, I was thrilled to be able to improve the metadata of and help facilitate access to the digitised images from the Hill and Adamson Collection as part of my role as Digital Collections Assistant.

Phoebe at work in the CRC office.

The Hill and Adamson Collection is made up of 701 calotype photographs that were taken between 1843-1847 by photographers David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson. They are some of the earliest photographs in history. As calotypes, they are different in their process from the more famous daguerreotypes which became the chosen process for photography. Calotypes are negatives which are made using paper coated with silver iodine, and specifically for Hill and Adamson, they used a type of ‘silver salted’ paper created by William Henry Fox. These calotypes in our collection are mostly of the 1843 Disruption, an event in which the Church of Scotland split, and the Free Church of Scotland was founded. The ministers who signed the Act of Declaration and Deed of Demission that signified this split are showcased in the portraits in this collection.

Other photographs in the collection include scenery of Edinburgh, such as Calton Hill and the Scott Monument, and laypeople of Edinburgh such as fishwives. It is an incredible collection that provides a snapshot into both the lives of clergymen, academics and laypeople in the 1840s in Edinburgh. Particularly, as photography was extremely expensive, and usually portraiture was at the expense of the subject, it is rare to find older photographs of laypeople. Therefore, this collection is very special in providing rare insight into these lives. Hill and Adamson were a powerful duo in the field of photography, but unfortunately Hill’s untimely death at the age of 26 in 1847 prematurely ended their partnership. Other collections of their works are kept at many different archives and museums around the world, further signifying the importance of their work to the fields of photography and history.

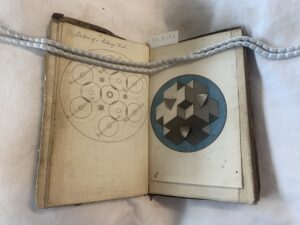

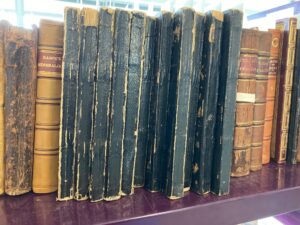

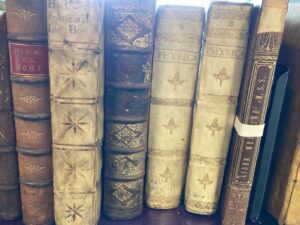

The aim of the project was to help provide better access to the digitised images of the Hill and Adamson Collection on the Library’s digital collections platform by providing fuller metadata for each photograph. The photographs’ descriptions were incomplete, and needed expanding upon. Creating information about the provenance and the people in the photographs, and then connecting this information to the existing digitised copy of the photograph was required. This was accomplished by looking through the physical collection, which is made up of 6 bound volumes, 4 loose-leaf collections kept in boxes, and one further box of photographs reproduced from the negative calotypes at a later time, from 1906 to 1920.

Most of the photographs were of white, upper-class men, who were members of the gentry, clergy, academia, or any combination of all three. Furthermore, the women in these photographs were very rarely identified by name, or even by relation to the man in the photograph, leading to confusion over their identities. Therefore, I made it my mission to identify as many of the women in the photographs as possible. However, within the collection, there were certain photographs that stood out to me as particularly interesting or novel, or providing key insight into politics and religion in the 1840s.

The Scott Monument

Coll-1073/7/45: Photograph of the Scott Monument in the 1840s.

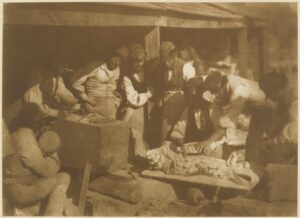

Coll-1073/6/9: Group portrait of workers building the Scott Monument, Edinburgh.

These photographs show the Scott Monument, and the masons working on carving a griffin for the construction of the Monument. These are beautifully shot and composed photographs that show a snapshot of 1840s Edinburgh, particularly the photograph of the Scott Monument, which we can see shortly after its completion in 1845, but before its inauguration in 1846. Many of the masons who worked on the construction of the Monument passed due to incredible back-breaking labour or respiratory issues from the stone dust. It is estimated that the monument killed half of all the masons that were employed to construct it due to lung disease.[1] Therefore, it is incredible to be able to see a photograph of those who worked on the construction, so they can be identified in some small way as those who contributed to such an iconic Edinburgh landmark.

Isabella (Burns) Begg

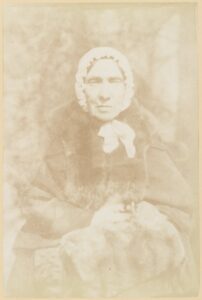

Coll-1073/1/24: Portrait of Isabella Begg (Burns).

This calotype shows Isabella Begg (Burns), youngest sister to Robert Burns, national poet of Scotland. She was born on 27 June 1771 and died on 4 December 1858, aged 87. She married John Begg at age 22, and had nine children with him. He died in 1813, leaving Begg a widow for 35 years.

Isabella was a valuable source of information into Burns as a poet, clarifying details of obscurity around his poems and stories, and identifying individuals in question. Her brother died when she was 25 years old. Begg has been identified as being 72 in this photograph, meaning it was taken around 1843.

This photo is one of the few photographs of women in the collection, especially one that has already been identified by the compiler. This portrait reveals a continued interest in Begg, despite the fact that Robert Burns had died nearly 50 years prior, and showed that she remained relevant to the Edinburgh community, as her photo was one of the first taken in the period of Hill and Adamson’s partnership.

Fishwives

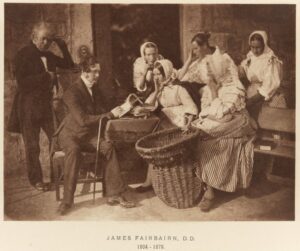

Coll-1073/3/8: Group portraits of James Fairbairn, James Gall Sen.r, and fishwives.

This group portrait is one of a number in the collection which showcases the fishwives of Edinburgh. As previously expressed, it is rarer to find photographs of the laypeople from this period due to the expense of photographic production. Fishwives were women who helped catch, prepared (i.e. cleaned and gutted), and sold fish. They were not always married, as wife here meant ‘woman’ and not ‘wife’. They were famed for being loud and outspoken, often swearing and presenting ‘uncouth’ behaviour that was not expected from women of the period. They were often self-sufficient as men were away fishing for long periods, therefore needing to help provide for themselves by successfully selling their wares. The Newhaven Fishwives (as shown in these photographs) were famous, even known to royalty. They were admired by Queen Victoria, and George IV thought they were ‘handsome’ (in the historical sense).[2]

Incredibly, four of the five women in this photograph are identified by name – Carnie Noble, Bessy Crombie, Mary Combe, and Margaret (Dryburgh) Lyall. The two men are identified as Reverend Dr James Fairbairn and James Gall. The calotype has been named ‘The Pastor’s Visit’ for this reason. This photograph potentially showcases James Fairbairn reading a pamphlet, perhaps religious, to the women, who sit in contemplation around him – focused? Or perhaps bored? – we cannot tell exactly. The posing for these photographs took around 3 minutes, a dramatic improvement from daguerreotypes which could take up to 15 minutes plus for exposure.[3]

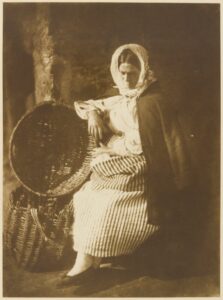

Coll-1073/5/34: Portrait of a fishwife.

Another portrait of a fishwife, this time an individual, also remarkably identified as Mrs Elizabeth Hall (Johnstone). This portrait, although posed again, provides insight into the typical clothing of fishwives of the 1840s. Although the photos are in black and white, we know that the Newhaven fishwives wore blue duffle coats and striped colourful petticoats, as well as a cap or headdress, and carried a creel which would have their fish.[4] All these items can be seen in this photograph, although unfortunately not in their striking colour.

[1] Tomlinson, Charles, “Stone”, in The Cyclopaedia of Useful Arts. Mechanical and Chemical, Manufactures, Mining and Engineering. Vol 2 Hammer to Zirconium, edited by Charles Tomlinson (London: James S. Virtue, 1854), pp.741–52.;

Donaldson, Ken, et al. “Death in the New Town: Edinburgh’s Hidden Story of Stonemasons’ Silicosis.” The Journal of The Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, 47.4 (2017), pp.375-383, doi:10.4997/JRCPE.2017.416.

[2] Bertram, James Glass, The Harvest of the Sea; a Contribution to the Natural and Economic History of the British Food Fishes, with Sketches of Fisheries & Fisher Folk (London, 1869), p.424.

[3] The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica (ed.), “Calotype”, Encyclopædia Britannica. Available at: <https://www.britannica.com/technology/calotype> [Accessed: 08 July 2025].

[4] Bertram, James Glass, The Harvest of the Sea; a Contribution to the Natural and Economic History of the British Food Fishes, with Sketches of Fisheries & Fisher Folk (London, 1869), p.429.