In this post conservator Amy Baldwin talks about working with the University of St Andrews to help develop their new arsenic identification tool.

You may have seen increased media coverage of the issue of poisonous green books in libraries over the last few years. As a result of research initiated by the University of Delaware in 2019, awareness of the presence of arsenic in nineteenth-century cloth and paper bindings has increased, and libraries around the world have been working out how best they can identify potentially arsenical books within historic collections and protect their readers and staff from any health risks.

It is worth noting at this stage that arsenic is not the only toxic substance which can be found in nineteenth-century bindings – mercury, chromium and lead are often present as well – so I would always recommend washing your hands after handling these materials, no matter what colour they are. But arsenic is of particular concern because copper acetoarsenite, the bright green dye in which it is contained, is very friable and likely to flake off cloth or paper covering materials when handled. Accordingly, the risk of it transferring to the person handling the book is higher.

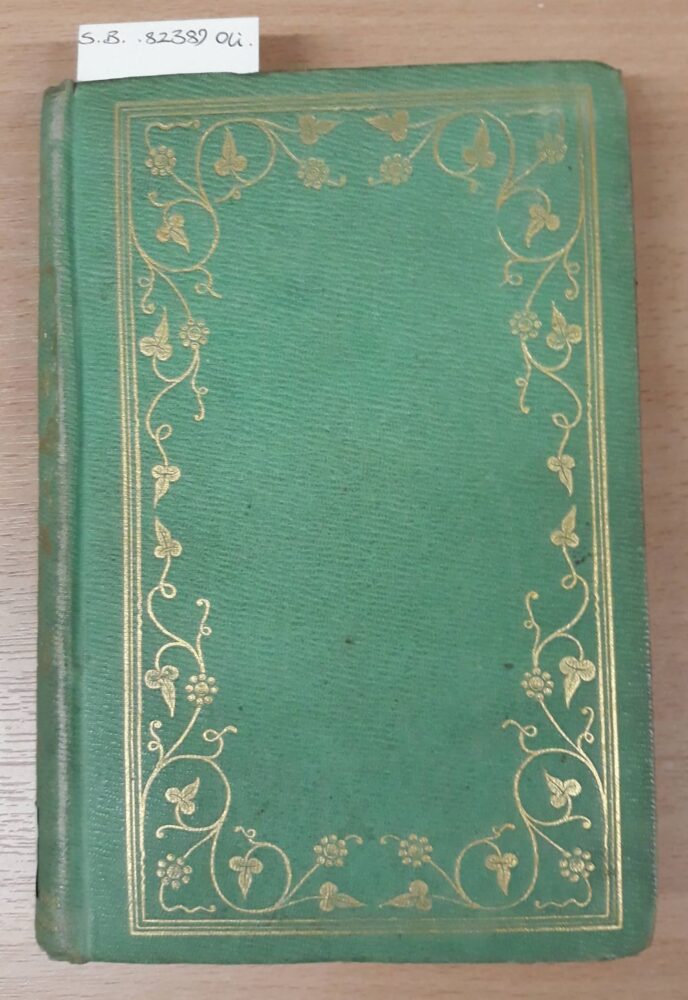

An arsenical book from the University of Edinburgh Heritage Collections

Being able to test books for arsenic is therefore key, so that libraries know which green books pose a risk and which ones are safe. Testing can be done in a number of ways, including using x-ray fluorescence, raman spectroscopy, and infra-red spectroscopy, but these all these involve access to expensive specialised equipment which is often unavailable to smaller institutions.

A team of conservators and scientists at the University of St Andrews have been working to address this issue by developing an affordable, handheld tool which can confirm the presence of arsenic in seconds. This has been adapted from a geological tool used to detect minerals in rocks, and it works simply by pointing the tool at a green binding and pulling the trigger. Results are immediate and simple to interpret.

Myself (second from right) and the team from St Andrews testing University of Edinburgh books using a prototype of the new tool

Having initially tried out the prototype tool on books from St Andrews, the team have been keen to access other collections to test it further, and at the University of Edinburgh we have been very happy to oblige! Our Rare Books collection contains many nineteenth-century books bound in cloth and paper so we are well placed to track down potentially arsenical volumes. This could have been like looking for needles in a green haystack, but fortunately not all green books are candidates. Copper acetoarsenite was used for dyeing bookcloth between the 1830s-1860s, so cloth-bound books from outside this date range are much less of a concern. It was used to dye paper throughout the whole nineteenth-century, but fortunately our collections feature far fewer paper bindings than cloth ones. By identifying storage areas with large nineteenth-century holdings, myself and colleagues were able to find 52 books which fit the criteria, which have been tested by the St Andrews team over the course of two sessions. They were tested with the newly-developed tool, and the results subsequently corroborated by raman spectroscopy.

A potentially arsenical book inside a raman spectrometer, ready to be tested

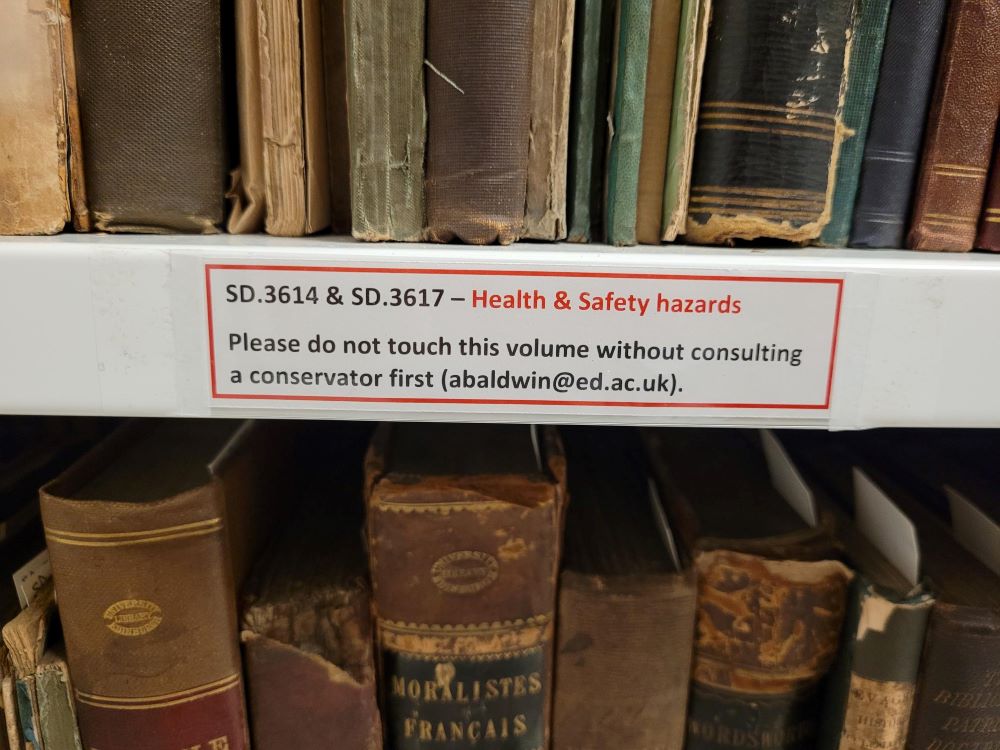

Of the 52 books tested, eight have tested positive for arsenic. I have been developing health and safety measures to ensure that the risk posed to staff and readers at the University of Edinburgh by our arsenical books remains as low as possible. Our aim in the Centre for Research Collections is to minimise direct handling, and to avoid producing the books in the reading room whenever we can. Currently, all the arsenical books have a label on their shelf with instructions not to handle. The next stage of the plan will be to place these books inside Ziploc bags, then put them in boxes with warning labels. This will further reduce the risk of their being handled, and prevent them from contaminating shelving and neighbouring books. Access still remains a priority for us, however – if an arsenical book is requested in the reading room we will attempt to source either an alternative copy in a safe binding or a digital surrogate. If the only option is to produce the arsenical copy, safe handling instructions have been produced for both staff and readers.

Current interim warning labeling

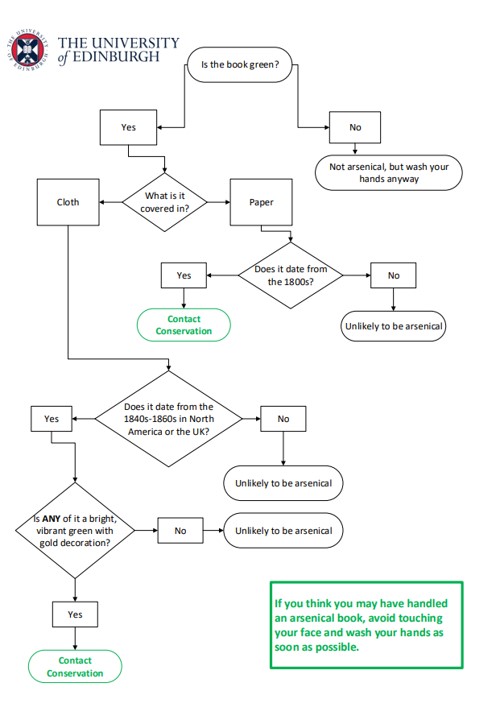

Realistically, we will probably find more arsenical bindings within our Heritage Collections in addition to the current eight. To help colleagues I have drawn up a flowchart, based upon resources supplied by the University of Delaware, which distinguishes between harmless bindings and ones which are worth testing. Arsenic poses a serious health risk, but by putting these measures in place and collaborating with projects such as that at St Andrews, we can shield our staff and users from this risk while learning more about the history and materiality of our collections.

A flowchart to help distinguish between harmless and potentially arsenical bindings

If you think you may have arsenical books in a collection you work with, resources and advice are available on the website of the Poison Book Project, hosted by the University of Delaware.

Fascinating!! May I ask which books were arsenical?

Hello Lynne, thank you for your comment. All our volumes which tested positive for arsenic will soon be listed on the Arsenical Books Database, hosted by the University of Delaware: https://sites.udel.edu/poisonbookproject/resources/arsenical-books-database/

This is such a fascinating collaboration, it’s impressive to see practical tools being developed to keep staff and readers safe while preserving these historic collections. Have you noticed any surprising trends in which types of books are most likely to test positive for arsenic?

Thanks for your question. Apart from the date range, there aren’t any consistent trends regarding what was bound with copper acetoarsenite – it seems to have been used across a wide range of subject matter. It comes up quite often on volumes related to plants and horticulture (not surprising really since it is a lovely green colour!) but it’s definitely not a hard and fast rule.