Home University of Edinburgh Library Essentials

December 15, 2025

AI, Openness & Future Publishing – Event summary

This is a guest blog post written by Veronica Cano, Open Data and REF Manager

The CAHSS Research Cultures team organised the half-day event “AI, Openness & Publishing Futures”, which took place at Edinburgh Futures Institute on the 13th November. Following our last half-day event earlier in 2025, “Open research issues and prospects in the Arts, Humanities and Social Science”, the focus shifted towards exploring the dynamic interplay between AI, open research, and the publishing industries. The event featured Dr. Ben Williamson, Dr. Lisa Otty and Dr. Andrea Kocsis, who each deliberated on how AI is reshaping research practices and publishing.

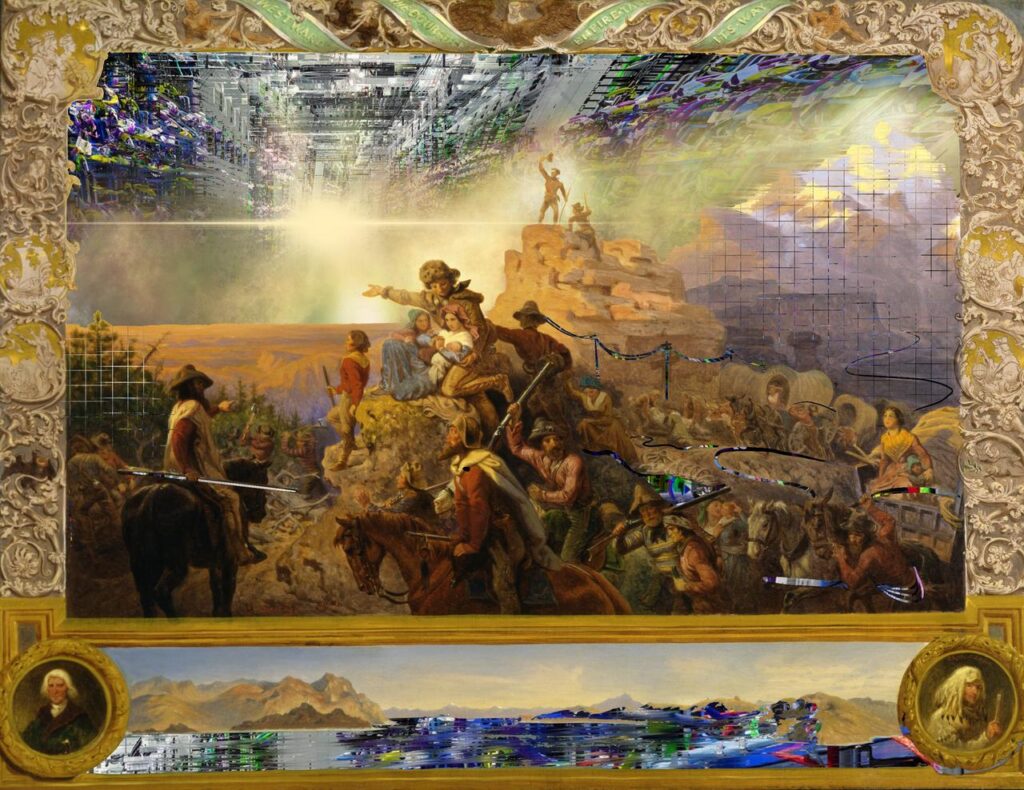

Highlighting risks of new forms of colonisation in the digital realm, this image was shared by Dr Otty as part of her presentationHanna Barakat & Archival Images of AI + AIxDESIGN / https://betterimagesofai.org / https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Critical Evaluation of Academic Content Commercialization

Dr. Ben Williamson shed light on the commercial motives of publishers and technology giants in harnessing AI for processing academic content. He drew on his recent work with Janja Komljenovic to argue that emerging publishing practices transform scholarly work into data assets, leveraging AI to maximise profits, often at the expense of academic integrity and control over research outputs. Referencing the work of Mirowski, he linked these developments to wider moves around commercialised platform science. Sharing his experiences as a journal editor, Ben highlighted instances where significant journal archives, like those from Taylor and Francis, were sold to AI companies, often without much transparency, underscoring a concerning trend toward the privatisation of academic knowledge and raising questions about the impact of this on open research and publishing.

Balancing Sustainability with Open Research Practices

Dr. Lisa Otty provided an analysis of sustainable AI use, noting the environmental impact associated with the growing computational demands of AI systems. She highlighted that while AI offers substantial benefits like efficiency in research and accessibility, it also comes with significant energy and carbon footprints. She suggested practical strategies such as using smaller, more efficient AI models and engaging in sustainable software engineering practices to mitigate the eco-impact of digital research tools. Making the most of the benefits of AI requires careful judgement about what is worth using ‘maximal computing’ for, and where more sustainable, possibly smaller-scale practices are appropriate and sufficient. More information about this is available on the Digital Humanities Climate Coalition web site: https://sas-dhrh.github.io/dhcc-toolkit/index.html.

Emphasising Open GLAM Data and AI Integration

Dr. Andrea Kocsis highlighted the longstanding engagement of AI within GLAM (Galleries, Libraries, Archives, Museums) sectors. Her presentation provided a historical timeline showing the evolution of AI technologies in these institutions, noting significant shifts towards more advanced machine learning and generative AI systems in recent years. Reflecting on the work being done at National Library of Scotland (NLS), including their advocacy for open data to foster research and innovation while ensuring ethical compliance and data stewardship, Andrea emphasized the necessity of responsible, open-data practices to mitigate risks such as bias and loss of metadata context which can accompany AI integration. Ongoing projects at NLS highlight both the promise of responsible AI in the GLAM sector and the creative possibilities unlocked by open data, exemplified by Andrea’s Digital Ghosts exhibition and its innovative use of web-archive material.

Community Response and Forward Thinking

The event moved on to a group discussion framed by extracts from blogs, reports and press articles on different issues regarding AI and publishing. The texts sparked thoughtful responses from the audience, generating insights on how the monetisation and privatisation of research is facilitated by AI and raising questions on what the open research community should do in the face of the risks posed by AI. Researchers’ pressure to publish frequently has become a playing ground for AI outcomes, resulting in unethical practices like papermills. The impacts are many, the erosion of public trust in research being a main one.

One of the attendees reflected afterwards: “… as it related to publishing, I got the impression that there was a sense of resignation, that it is too late, because the articles have already been sold and in many ways, we cannot opt out from AI (the google/bing summaries when you look something up, suggestions in Word, etc.) in our workplace, but also in our personal lives… Perhaps giving researchers advice on what individual action they can take, while showing what the sector is advocating for would be helpful.”

The role of higher education not only in grappling with current realities but in shaping future practices through individual and collective action was seen as extremely important, and conversations included how students can be engaged with these issues. Participants highlighted a need for ongoing dialogue and adaptive strategies as the landscapes of AI, open research, and publishing continue to evolve rapidly.

5 things: supporting you in your exams

Semester one is almost over and exams are looming! As the exam period approaches, it’s natural to start feeling the pressure build. But remember, you’re not alone!

At the University of Edinburgh, there are plenty of resources and services designed to support you every step of the way. In this post, we’ll highlight five key ways the library can help – from available study spaces and digital resources to helpful guides and wellbeing support – so you can make the most of your revision and head into exams feeling confident and prepared.

1) Study space, study space everywhere but not a place to sit?

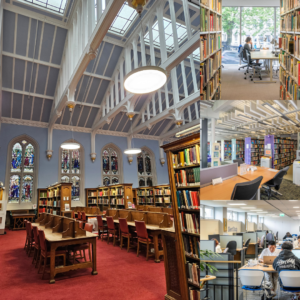

Clockwise from left: New College Library, ECA Library, Noreen and Kenneth Murray Library, and Moray House Library.

It can feel like this sometimes during the revision and exam period, particularly if you are a regular at the Main Library or Law Library. But there are lots of study spaces across our campuses that you have access to, including some temporary additional study space during the exam period.

While the Main Library is a favourite for many, there are 8 other site libraries that you have access to (with your student card). These range from old-fashioned, picturesque libraries, to modern libraries with light and space and also include a library in what used to be a swimming pool.

Shorthand in the New College Special Collections

by Danielle Fox, Archive & Library Assistant, New College Library

Shorthand writing, also known as tachygraphy, stenography, or brachygraphy, is a system of writing that uses symbols and abbreviations to represent words. This method allows the writer to transcribe speech at the same rate it is spoken, making it ideal for recording sermons, lectures, and court sessions. While modern technology has reduced its widespread use, shorthand played a crucial role in communication for centuries and existed in various forms. We are lucky enough to have many wonderful examples of shorthand in our New College collections.

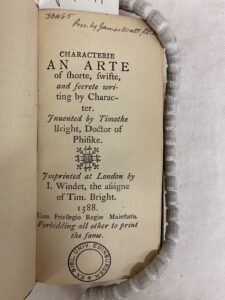

Bright, Timothy. Characterie (1588). University of Edinburgh, Heritage Collections. Df.9.141.

While shorthand can trace its origins back to ancient times, modern English shorthand systems largely emerged in the 16th and 17th centuries[1]. In 1588, Timothy Bright published Characterie; An Arte of Shorte, Swifte and Secrete Writing by Character, which introduced a refined system of shorthand that set the stage for future developments.

Other systems followed, such as Thomas Shelton’s Short Writing in 1626, and Isaac Pitman’s shorthand in 1837. Early English systems used arbitrary symbols for words or letters but eventually adopted phonetic systems. This meant that shorthand symbols focused on how words sounded, rather than how they were spelled, allowing writers to transcribe faster and capture the pace of speech.

Shorthand was especially popular in the 19th and early 20th centuries for tasks like journalism and secretarial work. However, with the advent of modern technology (like computers and voice recognition software), the use of shorthand has declined. Even though shorthand is less common today, it remains a part of history as a crucial tool for efficient writing. Read More

From tablets to computer screens; digitising some of the oldest texts at the University

by Elin Crotty, Archive & Library Assistant, New College

Over the past few months, the two New College Archive and Library Assistants (ALAs) have been liaising with the Cultural Heritage Digitisation Service (CHDS) about digitising our cuneiform tablets. The New College Library cuneiforms are 4 fragments of carved text, which range in date from the Neo-Babylonian Empire, (circa 626 – 539 BCE) to the Neo-Sumerian Empire (circa 2046 – 2038 BCE). The Neo-Sumerian tablet (NCL/Object/2025/3), which has split into two pieces, is thought to be one of the oldest examples of writing in the University’s collections at circa 4070 years old.

CHDS have recently been using Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI) to experiment with creating 3D representations of surface texture. You can read a much more thorough description of how the process works on their blog post here, but essentially the objects are placed upon a flat surface under a dome, with a camera positioned directly above them. Lights are fixed inside the dome at all angles and they flash in sequence as 72 photos are taken. This changes the light angle and resultant shadows for the camera, throwing details upon the surface of the object into high relief. The photos with the varying shadows are stitched together using specialist software, creating a 3D model of the surface of the object. A few months ago, the ALAs worked with CHDS to bring the New College cuneiforms to the uCreate MakerSpace, to use the RTI dome there.

The actual photography was very quick, but it was a careful process ensuring that the cuneiforms were supported and kept as flat as possible. After assessment by our conservation team, we built the fragments some temporary supports and handled them using nitrile gloves – no Hollywood white cotton gloves in our library! To get the cuneiforms in and out of the dome, CHDS had come up with a simple but very effective solution; a tea tray, lined with plastazote foam.

Figure 1 NCL/Object/2025/3, cuneiform tablet from Neo-Sumerian Empire (c.2046-2038 BCE).

Commonplace Book of Harriet Holmes

Today we are publishing an article by Ash Mowat, a volunteer in the Civic Engagement team, on the common-place book of Harriet Holmes, an 1818 – 1820 notebook which references a wide variety of material, from the voting and election system in Great Britain, to Icelandic musical instruments, to the dangers of pearl fishing in the Persian Gulf.

In this blog, we shall explore the common-place book of Harriet Holmes, an 1818-1820 notebook held in the University of Edinburgh’s Centre for Research Collections. [1] Harriet Holmes, later Harriet Spencer, shows a diversity of interests and subjects in her journal, which includes both observational writings of her own experiences, together with commentary of other texts and events. They clearly demonstrate her extensive and diverse level of education that would have been unconventional for a woman of the period.

The journal comes to an abrupt halt mid-sentence around the time of the birth of her son Herbert Spencer, who was to become a celebrated polymath with areas of specialism in many fields such as anthropology, philosophy and biology, having first employing the term “the survival of the fittest”.[2]

It is not always clear in her notes when she is referencing another author’s text and if so the identity of the source, therefore I have striven to mainly focus on pieces which are her own compositions.

(Image above from opening cover of the book).

In an early entry she is found recording English history from the 800s. “England is said to have been first divided into shires or counties by Alfred the Great. All our historians agree in representing him as one of the most valiant and best of Kings that ever reigned in England, and it is generally allowed that he….laid the first foundation of our present happy constitution. There is great reason to believe that we are indebted to this Prince for our trials by Jury’s.”

She goes on to examine, detail and question some current demographics on the voting and election system with Great Britain. “Electors of Members of Parliament for Great Britain: England has a total of 112, 875 eligible voters (all men, of course in this era), Wales 6752, and Scotland 2657, a total of 122,044. Should this be correct what proportion does the number bear by a population of nearly 12 million?”

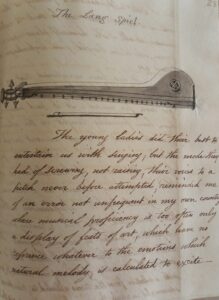

(An image from the notebook showing an illustration by Harriet Holmes and her written observations).

There then follows an account by Harriet of her visit to Iceland and of hearing a performance on the musical instrument native to this country. She was clearly impressed by the technicality and musical capabilities of instrument, if less enthused by and a somewhat harsh critic of Icelandic fiddle players and singing. [Note: if you would like to view a Langspil there is one on display in the Education Room at St Cecilia’s Hall]

“Description of the Lang Spiel (Langspil).[3] Having heard nothing of the kind before in Iceland, except the miserable scraping of the fiddle in the Reykjavik ball-room, the pleasure was now derived from agreeable sounds and harmonious music was very great. When our first surprise was over we thought that the music, which proceeded from the apartment above, was from a pianoforte, but we were told it was from an Icelandic instrument called the Lang Spiel, and that the performers were the son and daughter of Mr Stephenson, whose proficiency upon the instrument was very great. The Lang Spiel, which was brought down for our inspection, consists of a narrow wooden box about three feet long, bulging at one end, where there is a sound hole, and terminating at the other like a violin. The young ladies did their best to entertain us with singing, but the mode they had of soaring not raising their voices to a pitch never before attempted, reminded me of an error not infrequent in my own country, where musical proficiency is too often only a display of feats of art, which have no reference whatsoever to the emotions which natural melody is calculated to excite.”

Commenting further on the role and origins of Icelandic music she records some illuminating details that hint at the rich folklore embedded in the Icelandic arts. “It appears that music was known as a science-we were advised by Mr Stephenson and others that these were very old and native compositions.”

(In the image above, we see another fine example of the excellent artistic skills of Harriet Holmes, in this brilliantly captured image of a woodwind instrument, observed from several angles).

In another short piece, also on a musical note, she annotates the following attributed to Caroline Stephanie-Delicite (Madame De Genlis).[4] “Musical cascades, by an ingenious mechanical contrivance, the cascade in the garden of the Villa Borghese really performs Corelli’s beautiful sonata for the harpsichord and flute obligata. There is, at Naples, a musical cascade of the same description.” I was intrigued reading this on the nature of the instrument described but have not been able to identify what it was. It could be a work of fiction as De Genlis was a both a novelist and playwright, in addition to being an educationalist.

In her final entries she reports on her travels to the Persian Gulf and of the Pearl fishing trade. It is refreshing and welcoming that she takes time to describe, detail and empathise with the harsh working conditions of the divers employed in this industry, and of the hazards and hardships that they endure.

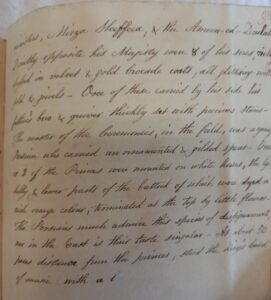

“Pearl Fishers- There is, perhaps, no place in the world where those things which are esteemed richer among men, abound more than in the Persian Gulf. The island of Bahrain, on the Arabian shore, has been considered the most productive bank in pearly oysters. There are two kinds, the yellow pearl which is sent to the Mahratta market, and the white pearl which is circulated through Bagdad and into Asia minor, and hence into the heart of Europe. The divers seldom live to a great age, their bodies break out in sores, their eyes become very weak and bloodshot. They can remain under water 5 minutes, and their dives succeed one after another very rapidly, as by delay the state of their bodies would soon prevent the renewal of the exertion. In general, they are restricted to certain regimes, and to food composed of dates and other light ingredients. They can dive from 10 to 15 fathoms (27 meters) and sometimes even more.”

The journal concludes still in Persia with an account of a royal equestrian event. “The master of ceremonies in the field was Persian who carried an ornamental and gilded spear. One of the two princes was mounted on white horses, the legs belly and lower part of the buttocks of which were dyed a rich orange colour, terminated at the top by little flowers”.

And thus, abruptly as above, the journal ends dramatically mid-sentence not to be resumed. According to the archive history halting at this point just as Harriet gave birth to her son.

It was fascinating to get this insight into early 19th century English life, from a well-educated writer who clearly both was a keen observer of life. and one with a diverse range of experiences and interests. It was a privilege to view this well- preserved journal, and I should like to express my gratitude to my supervisor Laura Beattie (Community Engagement Officer, University of Edinburgh) and to the library staff at the Centre for Research Collections.

[1] Collection: Common-place book of Harriet Holmes, 1818 | University of Edinburgh Archive and Manuscript Collections

Celebrating New Endings: Library & University Collections Publishes Updated Digital Preservation Policy

Excited to learn a defunct web forum for your favourite band as a teenager still exists in the Wayback Machine? Relieved to hear that a teaching resource will be supported even though the original platform has disappeared? Find it useful to cite a persistent link to your dataset you know will be there for decades to come when publishing new research?

There’s a day for that! World Digital Preservation Day celebrates good work in digital preservation across the community of practice responsible for the long-term care of digital resources. While we still have a long way to go, WDPD provides a moment to appreciate all the hard work already carried out against an avalanche of technological and social change.

Halloween Horror with BFI Player

With Halloween just around the corner, it’s the perfect time to get cosy and watch some truly creepy horror movies. Luckily, if you’re a student or staff member at the University of Edinburgh, you’ve got free access to BFI Player, packed full of wicked horror films (and other films) that’ll give you all the chills and thrills you’re after. From classic spooky tales to modern scares, there’s something for everyone who loves a good fright!

So grab some snacks, turn off the lights, and settle in for a scary movie marathon without ever leaving your room. Whether you’re watching solo, hanging out with friends, or just want to discover some fantastic horror flicks, the BFI Player’s got your Halloween covered with some seriously creepy must-sees.

Here is just a flavour of the horror films available to stream on BFI Player. Read More

Digital Research Services: What’s on This Semester

This a guest blog post written by Dr Eleonora Mameli, Research Facilitator in the Digital Research Services team.

To help the research community get the best out of the University’s digital resources, the Research Facilitation Team has organised a diverse programme of events for the 2025–2026 academic year.

From research planning to high-performance computing, there is something for everyone interested in using digital tools in research.

Digital Research Conference

The University of Edinburgh’s Digital Research Conference will take place on 26 February 2026, bringing together researchers, students and staff working with digital and data-intensive methods.

This year’s themes include:

- AI in Research: Promise, Pitfalls & Practice

- Digital Research Infrastructure & the Future of Research Computing

- Interdisciplinary Digital Research: From Humanities to Medicine

- Ethics, Security & Integrity in Digital Research

- Green Digital Research Practices & Sustainability

- Embedding Digital Tools in Research, Innovation, Teaching & Learning

Abstract submissions are invited for posters, lightning talks, and oral presentations. The deadline for submissions is October 20th at 5pm.

Find out more on the Digital Research Conference webpage.

Event Series

Spotlight on Research Planning

Join this bite-sized online seminar series, running every Tuesday from 21 October to 25 November at 12 pm. Open to academics, research support staff and postgraduate researchers, the sessions will cover:

- Data and computing cost estimation

- Research data management

- DMPOnline

- Project management

- Copyright and licensing

- Open Science Framework

More information at Spotlight on: Research Planning.

Introduction to Digital Research Services

The introduction to Digital Research Services (DRS) webinar runs on various dates throughout the semester.

It is perfect for newcomers, early career researchers (ECRs), or anyone who wants to get started with the University’s digital research tools and services.

HPC in Focus

Explore High-Performance Computing (HPC) through a mix of online and in-person sessions.

These events showcase the University’s research infrastructure, services and support, featuring expert insights, hands-on training, and networking opportunities.

Upcoming sessions will spotlight ARCHER2, the national supercomputer, and Eddie, the University’s local HPC cluster.

More details at HPC in focus training.

On-demand resource: Induction Video Series

If you would like to explore the University’s digital tools and services at your own pace, our Induction Video Series is a great place to start.

This collection of short videos is designed to help you navigate and make the most of the University’s digital tools, services, and resources.

Each video supports a stage of the research lifecycle, from planning and design to publishing and sharing data.

Watch the induction videos here.

If you would like to stay up to date with upcoming events and resources, keep an eye on the Digital Research Services website!

What will you discover at our Discovery Day?

Unlock the potential of your dissertation or thesis at Discovery Day!

Join us on Monday 27 October, 10am–2pm at the Main Library for Discovery Day, your chance to explore the amazing resources available for your dissertations and theses during our Dissertation and Thesis Festival. Read More

Welcome to the Library! Recordings and slides

Now that everyone is settling in to the new semester, we wanted to remind all students and staff that there is lots of material to help you use library resources for study and research.

In Week One we held live online sessions for PGT and PGR students, recordings of which can be found on the Law Librarian Media Hopper Channel:

If you missed them please feel free to use the videos to catch up, or download the slide decks attached to each video.

Last week we also ran an in-person on campus session for UG students. Although we didn’t record the session, you can find the slides for each part of the session below, or you can watch the PG session above for a similar introduction to library services.

UG Using the Library 2025-2026

Using Legal Databases – 2025-2026

If you require these documents in a different format please contact us by email: law.librarian@ed.ac.uk.

You can also contact us to book an individual appointment for a 30 minute one-to-one session where we can help with finding resources for research and study, referencing and making the most of library resources. Booking is available via the MyEd events booking system, or you can use the following links to find available time in our diaries.

Anna’s appointment booker

SarahLouise’s appointment booker

We look forward to hearing from you!

Collections

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Projects

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....