Home University of Edinburgh Library Essentials

December 23, 2024

Association for Historical and Fine Art Photography Conference 2024

The Cultural Heritage Digitisation service team have attended the annual Association for Historical & Fine Art Photography conference for well over a decade and have contributed to presentations at the annual conference. Susan Pettigrew the studio manager was Chair of the AHFAP Libraries and Archives Special Interest Group until the end of 2023. AHFAP is an important conference for CHDS in that it’s our network connection to the UK wide community of Heritage photography and digitisation.

Warm Wishes from your Law Librarians

With the exam period almost finished, it is time for all of us to get a well deserved break from studies, assignments and work in general. The University will be closed across the 2024 festive period from 5pm on Monday 23rd December 2024 and reopening at 9am on Friday 3rd January 2025.

The Law Library will remain closed for the period mentioned above. If you are studying or conducting research over the winter break you will find our online resources remain accessible via the usual channels, but should you run into difficulties we will not be able to respond to any messages until we return in January. Your Law Librarians will be away from Friday 20th December 2024 and coming back on Monday 6th January 2025.

The Main Library will remain open for most of the duration of the holidays but with reduced staffing and opening hours.

We wish you a restful and pleasant winter break during your time away from the University. See you in 2025!

~ Anna & Rania

Christmas Cards and Christmas Books

In honour of the upcoming festive season, Ash, one of our Civic Engagement Volunteers, looks for Christmas-themed items in the collection….

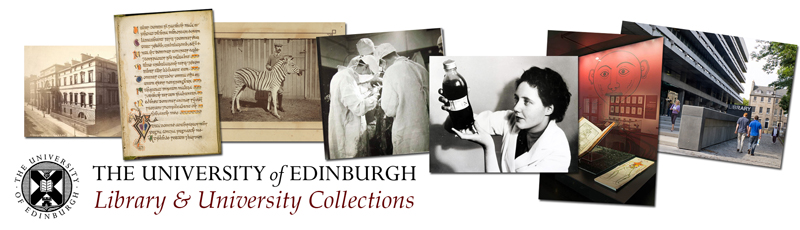

In this blog we shall explore a few items with a Christmas theme from the University of Edinburgh’s Heritage Collections. Initially I viewed two commonplace books from the 1850’s entitled “Mother’s Christmas book” and “A Christmas offering for our mother”, both featuring poetry, prose and illustrations whose creator’s identity is sadly unknown.[1]

The images above are from the cover and opening pages of the first volume dated Christmas day 1852, the portrait understood to be that of the artist and creator of the books. In the introduction he makes the following dedication:

“That dwelling within us, we can never feel alone on earth, entirely desolate. The gentlest name on earth, that lifelong love, whose presence makes enjoyment more enjoyed. That heart home for the weary ones is Mother”.

Perhaps a little saccharine in tone, but if you can’t be a little sentimental towards your own mother on Christmas day itself, that would appear somewhat harsh.

He then proceeds to compose a piece entitled “To a soot flake”. It is interesting to be inspired to choose something as prosaic and quotidian to form the subject of a work of poetry:

“Gently and softly thou comest down, borne upon the balmy air. Slowly and sadly thou sinketh down, like a soul overcome with care. And now again thou dost arise, caught by an eddy of wind. Whence didst thou first arise, floating upwards to the skies. In a cloud of smoke? was it from the flames so bright. The servant first awoke, and seizing on the sleepy child, fled away in terror wild.”

The switch between the piece of soot being wistfully observed to it becoming a threat and a danger seems to represent a common theme throughout the book of the juxtaposition between dark and light, taken by the author in outlining his Christianity.

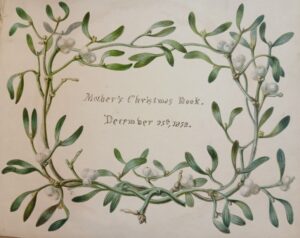

This is explored further in a fable entitled “A legend of Marsden Rock”, which recounts the story of a mysterious arrival of a boy wearing and gold necklace and crucifix who travels alone and is welcomed as a force of benevolence and good luck, protecting the fishermen and village people simply by his presence. A malevolent force, a “gloomy man” covets the gold chain and confronts the child to steal it from him.

In the sketch above, we see the gloomy man facing the angelic child with the obvious visual undertones expressed in the contrasting darkness and light of their depiction.

In the above illustration, we see the moment when the man meets his fate for his actions, being surrounded by a crowd of encroaching mermaids trapping him on a rock upon the sea. I love how the frantic horizontal lines help convey his sense of panic and entrapment, and how unformed and ethereal are the mermaids themselves, adding to their eeriness and menace.

“The man who never feared before looked around in mortal dread, the things came thronging close around, whenever he turned his head. At last he turned his glazing eye upon the mermaids’ cave, then with a fearful yell he dashed deep in the waiting wave. He went down like a ball of lead into a leaden grave. And then the blessed sun shone out and all was bright again.”

It is interesting to note the fusion between and religious parable and the usage of the ancient mythology of the mermaid, a folklore that predates the Christian period.

Another motif that the artist uses in his visual creations is the depiction of sleep and dreams. I love the mirroring going on in the drawing above. We have the writer at his poised to write, but his eyes are closed and he is asleep. Below him we see rendered his apparent dream. In it his head and shoulder form the shape of the trees. His Ink well and quill on the left become a tree stump, and the candle to his right is transposed to a brilliant sunset or sunrise.

Another representation of sleep and dreaming above, although nightmare may be a more accurate description. To modern eyes it is clearly reminiscent of the visitation of a vampire in bat format, however the period when this was drawn in the 1850s is some decades earlier than the publication of Bram Stoker’s Dracula in 1897, the first text to associate the legend of vampires with bats.

Whilst it is always a little sad and frustrating not to know the identity of the creator of such a creative treasure, it is nevertheless a privilege to have viewed it and to here enable others to enjoy the writings and illustrations.

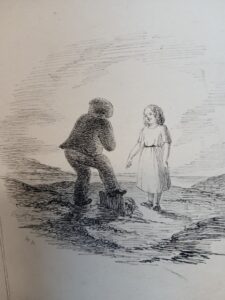

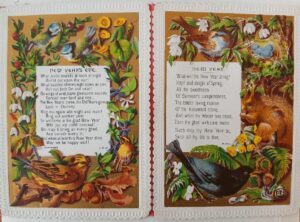

Although this text was entitled a Christmas book, it was not until later in the Victorian era that the type of decorations that we associate with Christmas today became more prevalent. Therefore, to infuse some of that artistic tradition into this blog I also viewed a collection of Christmas cards from 1878 as created by James Geikie (1839-1915),[2] Professor of Geology at University of Edinburgh. [3] Also included are items from a collection of Victorian printed ephemera.[4]

In the example above from 1874 there is a fine display of the intricate design and illustration skills being employed for simply an envelope containing a Christmas card. It features a beautiful border reminiscent in style of the Greek key meander motifs, with symmetric floral and symbolic patterns rendered in green, gilt and white tones.

Some examples of colourfully illustrated cards featuring festive robins and other animal surrounded by an abundant array of nuts and berries, inferring the promise of plentiful festive joys. The poems, including works by Agnes Stonehewer, however, emphasise the more traditional Christian qualities of the importance of gratitude, love and prayer at Christmas, together with hopes for health for the year ahead and the promise of Spring and Summer after the cruelties and challenges of a harsh winter.

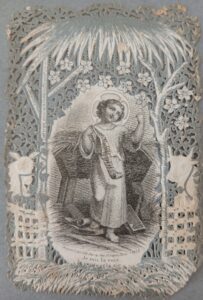

The above two French images depict the offerings to the Jesus with clear visual references to the birth in the manger, and of the one truth and light inherent in the Christian faith. They are exquisitely rendered on fine lace with the artwork resonant of religious depictions from centuries earlier.

Finally, for the those more inclined towards full on Christmas kitsch capers, what could ring the festive bells louder than an image of a child in a velvet coat and ruff feeding an infeasibly oversized St Bernard dog.

I hope this blog brings a little seasonal joy to all, and I should like to thank my supervisor Laura Beattie (Engagement Officer, Communities University of Edinburgh Heritage Collections) for advice and support, and to all the expertise and kindness of the staff at the Centre for Research Collections for enabling access to view these collections.

[1] https://archives.collections.ed.ac.uk/repositories/2/resources/83269

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Geikie

[3] https://archives.collections.ed.ac.uk/repositories/2/archival_objects/21442

[4] https://archives.collections.ed.ac.uk/repositories/2/resources/87197

Astronomical Observation of the planet Venus, Persia 1874

Today we are publishing an article by Ash Mowat, a volunteer in the Civic Engagement team, on the astronomical observation of the planet Venus from Persia, 150 years ago.

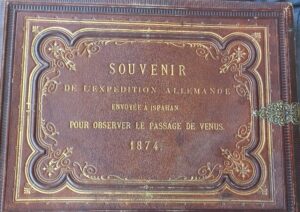

In this blog we shall explore a collection of photographs recording an astronomical observation of the passage of the planet Venus as viewed from Persia (now modern- day Iran) in 1874, held in the University of Edinburgh’s Heritage Collections department.[1]

The location of the events was in the city of Isfahan, currently the third most populated city in Iran and one that retains much of its celebrated historical architecture and art.

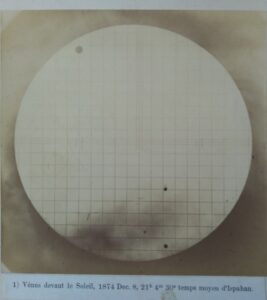

The photographs were to record the transit of the planet Venus in December 1874, a rare event offering enhanced opportunities to observe the planet in closer detail.[2]

(The image above shows the detail captured of the planet which is remarkable given the relatively primitive telescopes that were utilised).

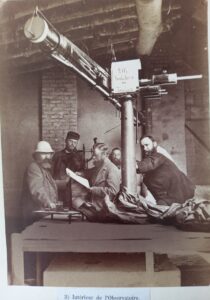

(In the image above, we can see set up of the larger format telescope that would have been used for the observations and photography of the passage of Venus. I like how it captures both the scientific equipment and the individuals engaged in their work, and not just a static pose before the camera).

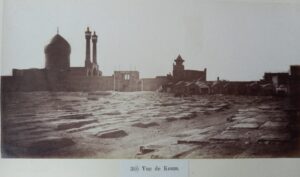

(In the above two images we can see a set-up of one observation area at Baugh-i-Zerecht bridge at Sende-Roud, a city gate and location of the Shah Mosque which was completed in 1629 and is now a UNESCO world heritage site)

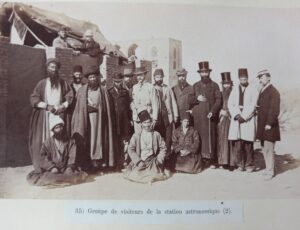

It is interesting to observe the variation between the two group photographs above, which were not positioned side by side in the folio, but that I have chosen to juxtaposite for the purposes of contrast. On the left the subjects depicted are the esteemed and privileged persons invited within the astronomical station, whilst the image on the right features a group of observers peering through the barrier of the perimeter gates.

The image on the left is more contrived, but perhaps purposely so to be a more official record, with the group members fixed rigidly for and staring towards the photographer. Many in the group are dressed in smart coats and top hats which add to the formality and might seem incongruous for the location.

I prefer the photograph on the right as here the subjects are much more natural, relaxed, and are not posing for or deferring to the photographer. The narrow depth of field utilised in the image nicely keeps its focus sharp solely on the central figures and blurs out the fore and background. Rather, their facial expressions and positions portray the connection and warmth between the group members, who might equally either be curious or indifferent to the events taking place within the gates.

(In the dramatic landscape image above, we have a brilliantly lit view of the Fatima Masumeh Shrine in the city of Qom. [3])

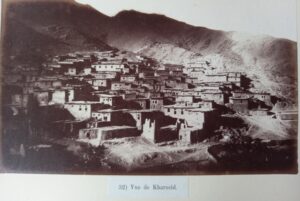

(I like this photograph for choosing to include the ordinary citizens homes of the period, perilously perched within the imposing mountains).

In conclusion, it was a privilege to view this stunning collection of photographs, clearly taken by a professional as the image quality, lighting and composition are of a great quality for the standards and capabilities of photography of this era. These images capture and preserve the dramatic landscapes of what was then Persia, and the people involved in the recording of this rare astronomical event.

I should like to thank my supervisor Laura Beattie (University of Edinburgh Community Engagement Officer) for support and guidance, and to all staff at the University of Edinburgh Centre for Research Heritage Collections for enabling access to view.

[1] https://archives.collections.ed.ac.uk/repositories/2/resources/340

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Passage_de_V%C3%A9nus

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Qom

Study Spaces in and around the Law Library during your exams

With the exam period already here and the need for more space to study and revise, one of the most common concerns for Law students is finding study spaces in the library.The Law Library is the favourite and preferred place to study but as spaces are limited, we have looked around the central campus for more options to manage demand during peak times.

From Pixabay (https://pixabay.com/photos/garbage-trash-litter-recycling-3259455/)

EXTENDED OPENING HOURS:

More information about opening hours for the Law Library specifically over the festive period can be found on the Law Library pages of the Library website. Please note that there are extended opening hours on Sundays in November (on 24th) and December (on 1st, 8th and 15th) until 18.50. Usual Sunday opening hours (open until 16.50) will resume in January.

STUDY BREAK CARDS:

Cards are situated around the library that can be used to keep your space while you take a short break. Turn the card to 15 minutes for a Short Break or fill out the time you intend to be away from your desk for longer breaks like lunch (up to one hour). This scheme has been shown to encourage healthy study patterns and help utilise the space we have available. We’ve used this system in the Law Library in the past and it’s gotten great feedback, so much so that it’s been extended to other libraries in our network.

ALL UNIVERSITY CAMPUS LIBRARIES (CENTRAL, KB, EASTER BUSH, WESTERN & ROYAL INFIRMARY)

Did you know that you can use any of the 13 site libraries that are part of the University’s library network? There are 5 within 5-10 minutes walk of the Law Library and the rest a bit further afield. Feel free to explore the different Library Locations

We believe this is a compromise that can work for students who need to use materials held specifically in this library without limiting who can work and study in the space. We understand Law students can feel that they should be prioritised when it comes to space in the Law Library, however the Law Library is part of the libraries’ network – including the Main Library, which also houses high use law books – and limiting access to one of these is neither possible nor fair. Law students also benefit from being able to use any of the campus library facilities – for example, did you know that the new KB nucleus is directly connected to the Murray Library and is open to everyone (including Law students)?

ADDITIONAL SPACES WITHIN THE SCHOOL OF LAW

For those of you that prefer to work within the space of the School of Law, there are additional spaces alongside any cafe facilities. You can also use the Dame Margaret Kidd Social Space and the Ken Mason Postgraduate Hub.

MORE STUDY SPACES AROUND THE CENTRAL CAMPUS

There are also temporary additional study spaces open at the Main Library and 40 George Square for study and revision. For all Postgraduates, the 5th floor in the Main Library is the place to be. And 40 George Square now features a Heat & Eat space! Details can be found of these and many other spaces across campus on the Study Spaces page of the website

And don’t forget, you can book group study rooms and student study spaces in all libraries by visiting the myEd Room Booking system (Booker).

Lastly, did you know about the Lister Learning & Teaching Centre? A beautiful space, not that far away from Old College, it offers space for teaching and revising. You can visit or book a space (through Booker) to revise or work on your assignments

All this information can be found in a handy leaflet we have prepared for you. Make sure you pick one up from the Law Library or download it and you can access the different locations by scanning the QR codes.

While we can appreciate the issues with finding space in the Law Library we find it a great compliment that so many students want to study with us. We are limited in the number of seats available but we hope you’ll understand we’re doing what we can to maintain a pleasant and peaceful study environment; the fantastic Helpdesk team are always on hand to assist where they can.

Our Helpdesk staff are ready to assist you in the library.

If you have queries or want to speak to someone directly about our libraries and collections, you can contact us by email: law.librarian@ed.ac.uk. We’d love to hear from you.

Outstanding Library Team of the Year – Times Higher Education Awards 2024

This is a guest blog post written by Dominic Tate, Associate Director, Head of Library Research Support

The University of Edinburgh’s Library Research Support Team, of which the Research Data Service is part of, won the ‘Outstanding Library Team of the Year’ category at the Times Higher Education Awards 2024 in Birmingham on 28th November. The team plays a central role in the institution’s transition to open research, with the impact of its work spreading far beyond the Scottish capital. The team created and implemented a UK-first rights retention policy, enabling scholarly work to be published in an open-access format while the authors retain the rights to their work.

Across the UK, 30 other universities have since followed Edinburgh’s lead, and the library team has also presented its work in India, Switzerland and the Netherlands. The team has already saved its university more than £10,000, with hundreds of thousands in savings anticipated in the years to come and millions expected across the broader university sector.

The library team’s new Citizen Science and Participatory Research Service, meanwhile, aims to boost public trust in science while facilitating research that depends on lived experience. By providing library spaces to researchers and community groups, the service enables collaborations on research projects, while the public can also access heritage collections and other library resources. The team endeavours to connect researchers with the communities around them, helping them answer research questions of public concern.

The judges applauded the Edinburgh library team’s initiative, commending its efforts to “share its experience with the wider sector” alongside its “emphasis on community access”. Its work, they said, “demonstrated a collaborative approach between the library research support team, academic and professional services staff, students and the local community that is scalable to other parts of the sector”.

The judges applauded the Edinburgh library team’s initiative, commending its efforts to “share its experience with the wider sector” alongside its “emphasis on community access”. Its work, they said, “demonstrated a collaborative approach between the library research support team, academic and professional services staff, students and the local community that is scalable to other parts of the sector”.

You can read an e-book profiling all the winners.

Ideas in Motion: Mapping Lyell’s Transatlantic Lectures

As part of our goal to ‘create a complete, comprehensive, and enhanced online catalogue,’ one series emerged as particularly in need of attention: ‘Lectures.’ Lyell Intern Claire Bottoms took on the challenge of untangling the numerous, often complex manuscripts, working to bring clarity and accessibility to this crucial part of Lyell’s archive.

Hello, I’m Claire, an intern who has been working on the Charles Lyell Collection offprints over the last 7 months. As part of our efforts cataloguing the collection this Summer, we were able to extend our work to one final element that needed attention: Lyell’s series of lectures, delivered in the UK and the US between 1832-1853.

Charles Lyell’s 20-year career as a lecturer started with two years (1832-1833) in London at King’s College London and at the Royal Institution; and extended throughout his travels in the US (1841-1853), where he presented across New York, Boston and Philadelphia. Records of these lectures exist as part of his archive, gifted to the University by his family in 1927, with additional series coming in recent acquisitions in 2020. Historic cataloguing of this series has been limited to them being simply labelled as ‘Lyell Lectures’, but as we began to sort through them, it was evident that they were early in date, and documented his rewrites and learning. “He revised, rewrote and rethought each lecture before it was delivered”, observed Leonard Wilson in his book Lyell in America (p372). We established that they would really benefit from some serious re-ordering, additional context and detail.

Two printed Lecture cards, produced for the Lowell Lectures at Boston October – November 1845, Coll-203/B14/9.

Given that there are already some sources on Lyell’s lectures, which when pulled together, promised to a comprehensive overview of his work, and, that there was some apparent order of folders within boxes, as well as historic typed lists (compiled by Lyell scholar Martin Rudwick), we embarked on the task of compiling a timeline and order of events to make better sense of these records. We were also able to gather information from a variety of resources: online newspaper records, print resources, previous archival notes, as well as taking a close look at the records themselves, including lecture cards which detailed the contents, venues and topics of Lyell’s lectures. With time and effort, we were able to map across to the archives Lyell and his team had preserved (clerk George Hall, Mary Lyell and Arabella Buckley), his own collection of manuscripts, lecture notes and drafts, newspaper cuttings and correspondence.

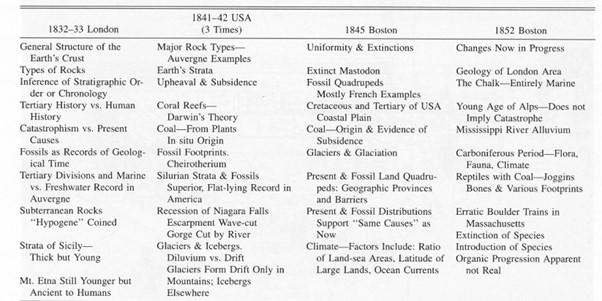

A very useful table by Robert H Dott, which maps out the contents of Lyell’s lectures, 1832 through to 1852

Two key sources we used were written in the 1990s, one being Leonard Wilson’s Lyell in America (1998), which is only available in print, and no longer available to buy; luckily there is a copy at the University Library. We also used Robert H. Dott’s article ‘Charles Lyells debt to North America: his lectures and travels from 1841 to 1853‘ published by The Geological Society of London, 1998. In light of this, the construction of a new and updated timeline brought together information that was otherwise scattered and tricky to access – into a cohesive reference for Lyell’s lecture history.

Long notes, on blue paper, and short notes on white, prepared for Boston Lecture on Erratic Blocks, of Berkshire Massachusetts, 16 November 1852, reference Coll-203/B14/15.

Lyell appeared to work on, and organise his lecture notes, using a system of “long notes” (extended pieces of prose), and “short notes” (smaller booklets in numbered shorthand of the same content, often accompanied by timings and lists of illustrations). It is fascinating to see this process of writing, revising and refining his work, which allowed Lyell to hone his scientific ideas and communication skills; portions of these notes appear to make their way into Lyell’s later published works. Published sources describe Lyell as having been initially reluctant to teach and lecture, instead being eager to devote his time to his emerging writing career. The lecture series are credited with providing him with both the additional income, and the scientific recognition to do this. Notably, though Lyell was once a nervous public speaker (sources recount him dropping his notes once during his first lecture), this process likely helped develop a more polished and accessible approach.

Illustrations as delivered at the Lowell Lectures, Boston, 19 October 1852 – 26 November 1852, reference Coll-203/B14/15.

Original newspaper wrapping enclosing Lecture 5 Prose notes, from The Express, dated 19 March 1850, reference Coll-203/B14/12.

The archival records go beyond recording Lyell’s words, they also contain diagrams outlining Lyell’s plans for his lecture layouts, referencing the illustrations intended to support his presentations. It is apparent he travelled with these illustrations, as well as commissioning new ones on his way – sadly they’ve not survived, most likely victims of steamship voyages! Lyell’s lectures are also accompanied with older notes, articles and pieces of research that he brought together to use as material in his lectures. In many cases, all of these associated records are enclosed in newspaper wrappings. These wrappings added an unexpected additional layer of archival interest, and have been helpful in identifying the date, location and corresponding lecture.

Mapping Lyell’s selection of lecture materials has been a challenging changing process, with new pieces of information, resurfacing parts of the collection, and decisions regarding how to order the series emerging at every turn of the page! Yet, it has been incredibly fascinating and rewarding to see it all come together under a new timeline we are proud to have compiled and used to make sense of these folders, no longer only detailed as just ‘Lyell’s Lectures’.

Thank you, Claire, for transforming how Lyell’s ‘Lectures’ are presented in the catalogue. While still respecting the original acquisition details and their division into two sections, the information is now far more detailed. It reveals draft prose that Lyell would later incorporate into Principles, and, with the material now organized by lecture location, it’s much easier to trace how Lyell criss-crossed the Atlantic. Check out the details in sections Coll-203/8 and Coll-203/B14.

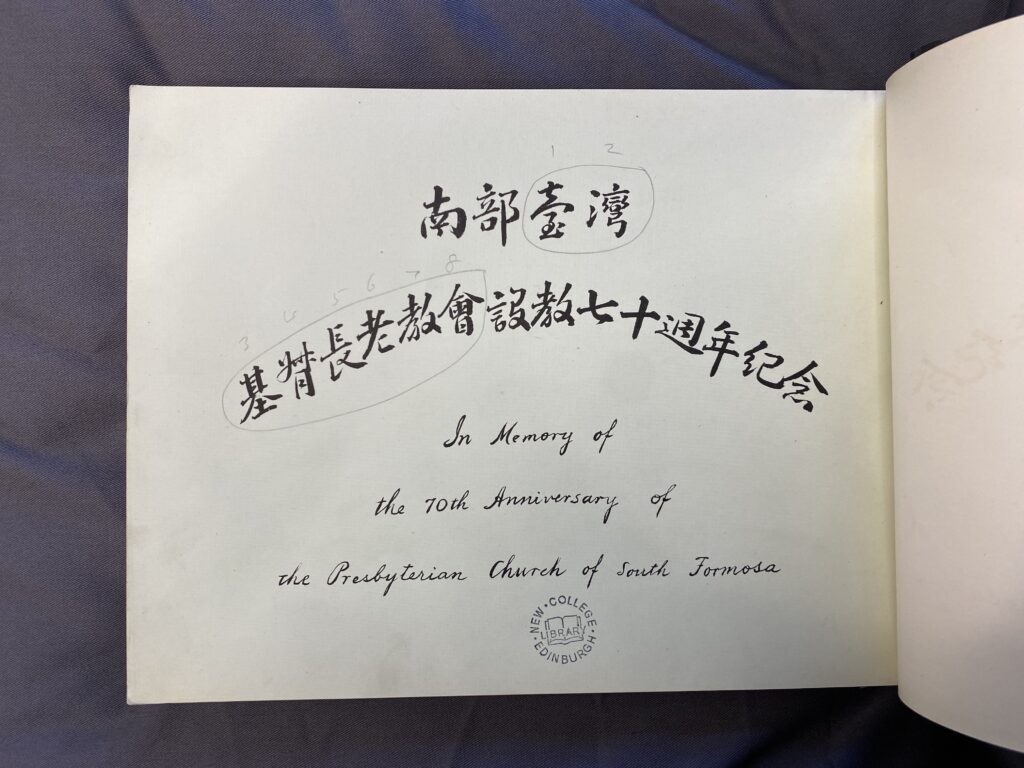

Celebrating the Presbyterian Church of South Formosa

In memory of the 70th anniversary of the Presbyterian Church of South Formosa

南部基督長老教會設教七十週年紀念寫真帖

“In memory of the 70th anniversary of the Presbyterian Church of South Formosa”

Yi-Chieh Chiu, Library Collections Services

During recent cataloguing work at New College Library, this interesting volume was discovered in the open access folio sequences and subsequently moved into New College Rare Books. The book is entitled In memory of the 70th anniversary of the Presbyterian Church of South Formosa and there are very few extant copies of the original edition remaining, with only one known copy in Taiwan.

From Norwich to New College: Revelations of Divine Love and the NCL Collections

This blog post by Elin Crotty (Archive and Library Assistant, New College) spotlights some of the special collections material at New College Library, and explores the connections between our manuscripts, art, and published texts.

You may have heard of Julian of Norwich from an introductory English Literature course, or from a more specialised study of religious persons in the Middle Ages.[1] Julian, also known as Juliana, was a fourteenth-century anchoress at St Julian’s Church, Norwich – that is, she went into seclusion and was willingly walled into a cell in the church, with only a cat for company.[2] Her works, Revelations of Divine Love, are commonly viewed as the earliest English language writing that can undeniably be attributed to a woman. Revelations focusses on Julian’s visions (sometimes referred to as “showings”) of Christ during an illness, and she provides theological interpretation for some of the meaning behind her experiences. The work exists in two forms; the “Short Text”, which was written shortly after her illness, and the “Long Text”, which underwent many more versions and revisions.

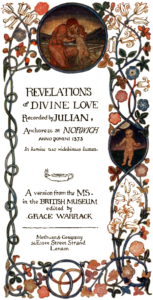

Figure 1: Julian of Norwich, Grace Harriet Warrack, Methuen, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

We do not hold a copy of Julian’s “Short Text” in the archives at New College – our collections are quite impressive, but sadly the original manuscript is lost.[3] The “Long Text” also only exists through copies, which were made by sixteenth and seventeenth century nuns. Versions are currently held by the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (MS Fonds Anglais 40), the British Library (MS Sloane 2499 and MS Sloane 3705), Westminster Cathedral (MS 4 (W)), and a few other partial copies and extracts also remain.[4] There was not a printed version of either the short or the long text available until 1670, when Serenus Cressy, a Benedictine monk, published a copy in Paris. This was reissued in 1843 and 1864, and the text began to become more well-known with the 1901 publication of a modern English version by Grace Warrack. This version featured an illustrated title page by the artist Phoebe Anna Traquair.

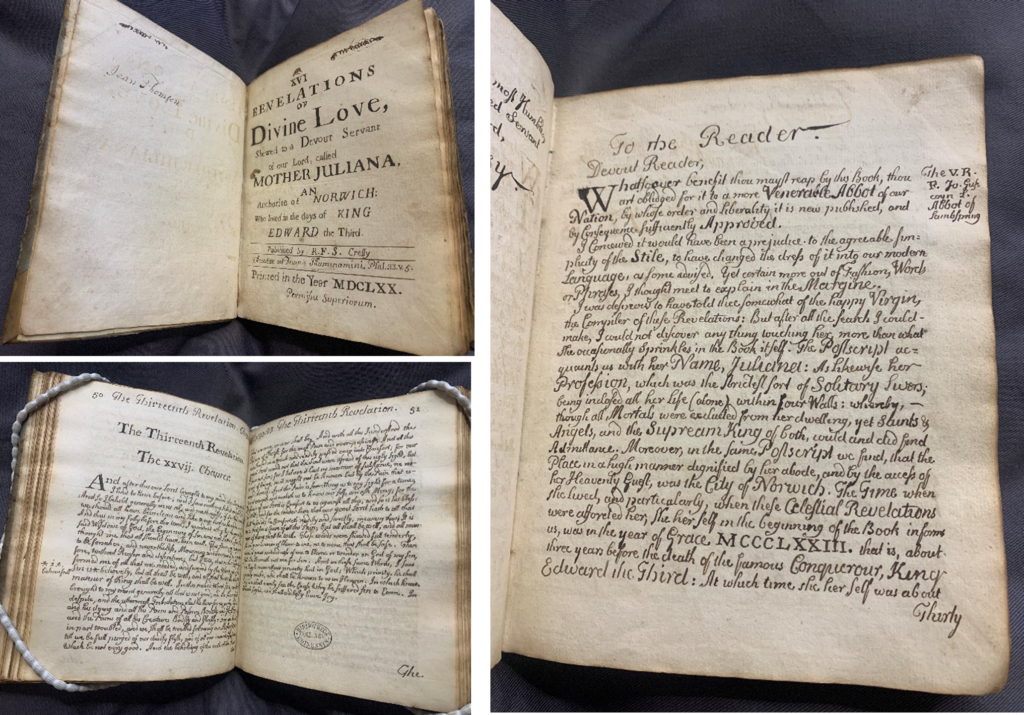

You may be asking by now, what does this actually have to do with the New College Library collections? Well, ongoing improvements to the archives catalogue have recently brought MS CRE out in the Funk Reading Room. It’s a manuscript copy of the Long Text, but all it not quite as it seem here. Rather than being a copy of another manuscript, MS CRE is a wonderful example of a published book that was then copied entirely back into a manuscript format. This may have been done as an exercise of devotion (given the religious topic), or perhaps for more practical purposes such as saving cost and practicing italic calligraphy.[5] The scribe – unknown to us – carefully copied the format of the title page and printing details, as well as clarifying annotations that would have been printed in the margins. There is an inscription ‘Jean Thomas’ on the front flyleaf opposite the title page, and some twirly pen trials where a past reader scribbled away with no discernible purpose. Unfortunately, we’ve no way of knowing whether Jean wrote the book themselves, or if they were a former owner at some later date. It has laid paper with clear chain lines and a distinct watermark. The quarto volume is half bound, with fairly basic materials; the boards are cardboard and show signs of previous repairs.

Figure 2: Pages from MS CRE. New College Library Special Collections, University of Edinburgh.

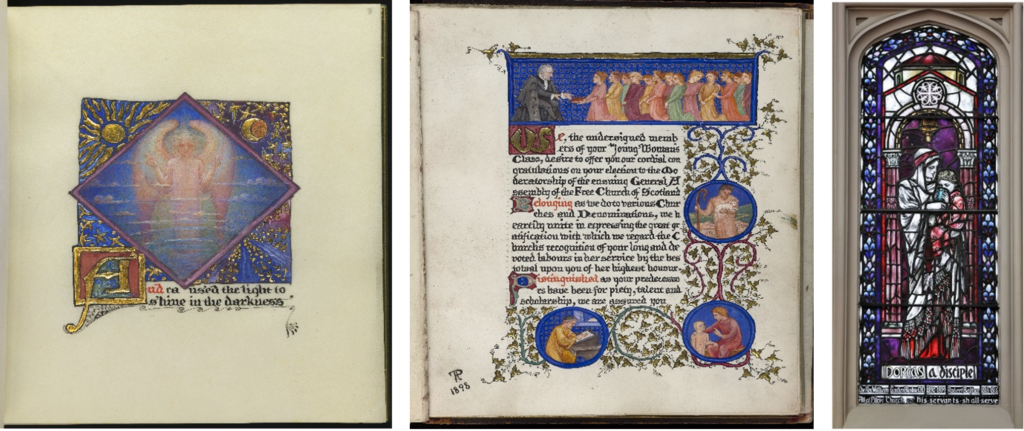

MS CRE is not the only copy of Revelations in our collections, or our only link to the history of the text. We also have tJG4JUL 1901, which is a copy of Warrack’s 1901 edition.[6] Art commissioned by Grace Warrack is all around us at New College, as Warrack gifted the stained-glass windows in the Library Hall. The artist who designed and created them, Douglas Strachan, spent over 20 years working very closely with Warrack. Warrack was averse to featuring depictions of suffering and evil in the biblical scenes, which may be why it took so long to plan and implement the windows.[7] At that time, the Library Hall was positioned elsewhere in the New College, and the beautiful stained glass adorned the High Kirk of the Free Church of Scotland.

Figure 3: Left: Gen.852, f.3r. Heritage Collections, University of Edinburgh. Centre: MS WHY 42, f.2r. New College Library Special Collections, University of Edinburgh. Right: Window 10 of Library Hall.

Additionally, further creations by the artist Phoebe Anna Traquair can be found in both the New College Library collections and at the Centre for Research Collections, in the Main Library. Our item is a beautiful presentation piece that sits within the collection MS WHY (Papers of Rev Prof Alexander Whyte (1836-1921)), which was given to Prof. Whyte in 1898 by the Young Women’s Class, to congratulate him on his appointment as the Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland. Only the first few pages of the volume are illuminated, and the rest of the text is a list of signatures. The Traquair work at the Centre for Research Collections is known as Gen.852. It is a book of reproductions of the beautiful medallions painted on the walls of the Song School, St. Mary’s Episcopal Cathedral, Edinburgh, 1897.[8]

If you would like more information about the New College Library Special Collections, or to book a research appointment in the Funk Reading Room, please email us at heritagecollections@ed.ac.uk. We are open to all; new and experienced researchers, staff, students, and members of the public – anyone with a desire to explore our collections is more than welcome to get in touch. The Heritage Collections team would be thrilled to support your research and provide expert curatorial advice. You can find links to our catalogues and further information on accessing our collections on our webpages.

Post written by Elin Crotty, Archive and Library Assistant (New College)

[1] For a very thorough overview, see Markham, Ian S. The Student’s Companion to the Theologians, John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, 2013. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ed/detail.action?docID=7103732.

[2] Julian is sometimes referred to as the patron saint of cats, or as the original “cat lady”. Here’s a podcast by Dr. Jesse Njus and E.H. Lupton, which explores the connection between anchorites and cats in more detail. Njus and Lupton. ‘Episode 5: Hermits and Anchoresses’ in Ask a Medievalist. 14 May 2020. Notes accessed 20 November 2024 via http://askamedievalist.com/2020/05/14/episode-5-hermits-and-anchoresses/

[3] The only known copy of the short text is British Library, Add MS 37790, which dates to around 1420. https://www.umilta.net/tablet.html

[4] Possibly the most comprehensive resource for exploring the various manuscripts of Revelations is Julia Bolton Holloway’s ‘Julian of Norwich, her Showing of Love and its contexts’. Published in The Tablet, 1996. Accessed online 20 November 2024 via https://www.umilta.net/tablet.html

[5] Whilst writing this blog post, I went down a wonderful rabbit hole trying to find out how much a book like Revelations would have cost in 1670. The answer is, it really depends – on the covers and binding, on the size of the type and the volume, on the materials used, and on the size of the print run. This article by David McKitterick has information about an upper-class family’s account books and purchasing habits for their library in the early to mid-17th Century. The books they purchased were anywhere between just a few pence and several pounds per volume – that’s from less than a fiver up to several hundred pounds in today’s money. McKitterick, David. “‘Ovid with a Littleton’: The cost of English books in the early seventeenth century”. Transactions of the Cambridge Bibliographical Society, vol. 11, no. 2, 1997, pp. 184–234. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41154865. Accessed 20 November 2024

[6] You can read more about Grace Warrack and tJG4JUL 1901 in this blog post here: The woman behind the windows at New College Library | New College Librarian. There are several notes between Warrack and the New College Librarian interleaved in the pages.

[7] If you’d like to know more about our amazing windows, please visit the reception desk in the Library Hall and pick up a leaflet. You can also see another of Strachan’s windows in the Martin Hall at New College – catch a glimpse on the School of Divinity website here: https://exhibition.div.ed.ac.uk/martin-hall/

[8] The full catalogue entry is available here: https://archives.collections.ed.ac.uk/repositories/2/resources/219

Celebrating a new batch of recordings just added to the RESP website

The factory floor in Brunton’s wire mill, Musselburgh. Thanks to the John Gray Centre Archive for sharing this image with us. (ref. ic-af-229)

For this blog post, which marks the most recent upload of recordings onto the RESP Archive website, we are delighted to hear from Mark Mulhern, Senior Research Fellow with the EERC and lead for the RESP Spoken Word strand.

This latest batch of recordings to be added to the RESP Archive website is in some ways representative of how the RESP goes about including different voices in its collection. Within this batch, which includes 24 fieldwork interviews, we have recollections about:

- The mills in Musselburgh – Brunton’s, Stuart’s and Inveresk paper mill

- One man’s (David Elder) recollections of his early life, National Service and more

- Recollections for workers at a number of enterprises at Gateside Industrial Park, Haddington

- One woman’s (Sheila Murray) recollections of her life in Peebles and her connections to the textile mills in the town

- A recording made in 1973 of Mrs Blacklock on the occasion of her 100th birthday

Friends Sheila Fraser and Kathryn McMillan shared their memories of working together in the Brunton’s wire mill offices (EL6/21)

Within this batch of recordings there is a variety in content and also in the way in which these recordings became part of the RESP:

- The Musselburgh Mills recordings came about as a result of new fieldwork conducted by myself, largely within Musselburgh Museum.

- David’s recording was made by an existing group within the John Gray Centre – the Active Memories Group.

- The interviews of those who worked at the various industrial enterprises at Gateside in Haddington were conducted by members of Haddington’s History Society as part of a project that they ran in partnership with the RESP.

- Sheila’s recording was made by my colleague Caroline Milligan. This interview came about as a result of Sheila having read and enjoyed our recently published book Border Mills: Lives of Peeblesshire Textile Workers

- The recording of Mrs Blacklock was donated to the RESP as a result of Mrs Blacklock’s grandson – her interviewer in 1973 – coming across our work in D&G and asking if we would be interested in adding his recording of his granny to the RESP Collection

As can be readily discerned, material comes to the RESP in a variety of ways. The common factor with this batch of recordings is that their inclusion came about as a result of the RESP being active within and receptive to the communities with which we work with. This is true of this batch of recordings and also reflects the wider ethos of the RESP in which we seek to enable communities to create, preserve and share their recollections.

Another salient point about this batch of recordings is the variety of content. These 24 recordings cover industrial employment, childhood, National Service, work in a number of mills across lowland Scotland and the recollections of a lady who was born in 1873. This diversity is also reflected across the wider RESP Collection.

David Dixon (EL6/24) shared memories of his working life and connections to Brunton’s wire mill.

This range is in and of itself of great importance to the RESP as we seek to provide a space to enable folk to talk about what is of interest to them. Such an approach almost inevitably leads to a collection with diverse content. That diversity of content is a reflection of what is of interest to people in different places. A collection of individuals speaking about what is of interest to them tells us what is of importance to them. In this way, the RESP is establishing a body of work that, for now and the future, tells us something about the commonalities and differences of lives lived in different places and at different times across Scotland. Key to enabling this is the open and receptive approach taken in conducting and managing the RESP.

The Tandberg Goats were moved to their current location in Haddington after Mitsubishi took over the Tandberg plant at Gateside.

This work continues!

Mark Mulhern

Nov 2024

Collections

Archival Provenance Project: Emily’s finds

My name is Emily, and I’m the second of the two archive interns that...

Archival Provenance Project: Emily’s finds

My name is Emily, and I’m the second of the two archive interns that...

Archival Provenance Project: a glimpse into the university’s history through some of its oldest manuscripts

My name is Madeleine Reynolds, a fourth year PhD candidate in History of Art....

Archival Provenance Project: a glimpse into the university’s history through some of its oldest manuscripts

My name is Madeleine Reynolds, a fourth year PhD candidate in History of Art....

Projects

Sustainable Exhibition Making: Recyclable Book Cradles

In this post, our Technician, Robyn Rogers, discusses the recyclable book cradles she has developed...

Sustainable Exhibition Making: Recyclable Book Cradles

In this post, our Technician, Robyn Rogers, discusses the recyclable book cradles she has developed...

Giving Decorated Paper a Home … Rehousing Books and Paper Bindings

In the first post of this two part series, our Collection Care Technician, Robyn Rogers,...

Giving Decorated Paper a Home … Rehousing Books and Paper Bindings

In the first post of this two part series, our Collection Care Technician, Robyn Rogers,...