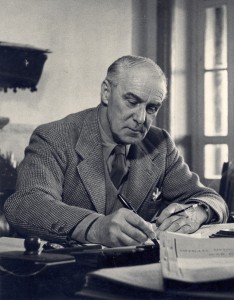

Francis Albert Eley Crew (1886-1973) had a distinguished career at the University of Edinburgh as director of the Institute of Animal Genetics and Buchanan Professor of Animal Genetics, and later as Professor of Public Health and Social Medicine. But at the time of the First World War he was a newly qualified medic with a small rural practice in Devon and a young family. His war experience profoundly affected his future career, spurring him to leave medicine behind to follow his real passion: genetics. Crew provided a vivid account of his war years both in oral history form and in a written memoir, both of which are held here in EUL Special Collections.

When war broke out in August 1914, Crew was at summer camp in East Devon with the Devonshire Regiment 6th Battalion of the Territorial Army, with whom he had been enthusiastically involved in his local village. What began as a summer holiday ended in a flurry of intense activity as men rushed forward to be recruited into the army. Crew and thirteen of his fellow men from his village, became the 2nd 6th Devons, bound for India. Although Crew was medically qualified, and therefore eligible to join the Royal Army Medical Corps, he wanted to see ‘active service’ and so kept his qualifications a secret.

Crew quickly formed the opinion that the organisation and training were a ‘ragbag of inefficiency’ and ‘complete chaos’. Many of his senior officers were ‘of the Boer War vintage’ with outmoded ideas; at the age of 28, Crew found himself rapidly promoted to the rank of Major and in command of a company. His battalion sailed for Bombay on 12 December 1914, leaving his wife Helen heavily pregnant with their second child. Conditions on board were somewhat chaotic: ‘The overcrowding was such that no kind of training could be undertaken and the voyage was so long that by the time we reached the Ballard Pier, Bombay, the troops were in a sorry state and found the march to the barracks at Colaba far beyond their powers.’

Once in India, the batallion came under the orders of the 6th (Poona) Divisional Area at Bombay, and Crew was sent to Deolali, where he was made responsible for field training and for the maintenance of law and order in the area. After the elderly Commanding Officer was sent home on medical grounds, Crew duly became second-in-command of a wing of the battalion, ‘with somewhat vague duties.’ Crew had enough on his hands playing ‘mother’ and ‘father’ to the young men who had come along with him, and all of whom (except one ) had never left Devon before and were totally lost in this foreign land. He spoke of his feelings of loneliness and isolation which came with promotion: ‘if you’re in command of a couple of companies of troops or a battalion or of a field ambulance, then you are isolated from all your colleagues, I mean you’re responsible for them and they can share very little with you.’

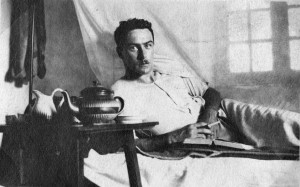

Crew was then sent to Muttra, south of Delhi, with two companies, and then up the Khyber Pass, where they commanded a fort. By this time, Crew was growing frustrated that his duties were confined to training men to fight while not seeing active service himself. But change was on the horizon. Crew developed amoebic dystentry – ‘quite deliberately’ he later wryly remarked – and became seriously ill. He was sent to Bombay to the embarkation authorities, for return to the UK. At this point, his medically qualified status was discovered, and, after a short period of rest and recuperation, Crew was posted to France, where he took over control of the stretcher-bearers in the No. 3 Field Ambulance at Arras. It was intensely dangerous work, Crew received his first wound on his second day, at Bern-Villiers, south-east of Arras:

I was sent up into the line to take over from a Major Anderson, who was running the forward work of the ambulance doing all the clearing, and he took me round all the eight-posts in front and we came back and I was marking them on my map in a small Armstrong hut, I think they called them – little cardboard thing, struck up against the face of a hill. And he was sitting down on a table and I was bending toward him as we made the marks on the map, and all of a sudden there was a terrific flare, glare, crash, noise and everything disappeared in smoke and fume and I found myself – when I came to – jammed under the seat. I’d been blown under the seat for some reason or another. I got out with great difficulty – I was wounded rather badly – and there was poor Anderson sitting on the seat…and he’d got a sliver of shell casing that long and that wide sticking out of his chest. I got that out and tried to do something for him but it was hopeless, hopeless, hopeless. So he died there promptly in my arms, and that’s not a good introduction to a war by any means.

Crew was to receive two more wounds during his time in France. These harrowing experiences naturally affected him profoundly, and he became convinced that he would not survive: ‘I didn’t bother about tomorrow and the day after tomorrow, I didn’t think there was going to be one.’ It was not until the war was reaching its end and victory seemed likely that Crew was suddenly assailed by the realisation that he might indeed have a life to return to – what was he going to do when he returned to normality?

There was no doubt at all that we were winning, and winning fast, and consequently I began to think that possibly there was a future. And so, when once that question asked itself, the second question followed: what do I do? You see, I’d been five years away from anything. Complete waste, complete waste – from my point of view. There was hardly a book, there was hardly a thing you could get hold of. And I was sitting, I was living in a hole in the ground, hanging my accoutrements upon the skeleton hand of somebody who’d been buried there years before, and under those completely gruesome conditions, one began to wonder what one was, what one wanted, what one wanted to be and so on and so forth. And it was very interesting, the speed and the clarity with which I reached my decision. I was going to be a geneticist.

Crew received his demobilisation in early 1919, after a demoralising experience overseeing anti-venereal work in Cologne. The war had filled him with a sense of urgency: an awareness of wasted years, a lack of intellectual stimulation and the constant threat of annihilation. Now it was all over, he was filled with a new sense of purpose:

I had discovered much about myself under the stresses of great fear, of intense boredom, of much disillusionment. I came to know that I could find satisfaction only in the academic world and in activities connected with the genetics and reproductive physiology of animals.

Crew returned eagerly to Edinburgh with the intention of studying genetics at the University under Arthur Darbishire. Unexpectedly however, Crew discovered that Darbishire had died during the war. Even more unexpectedly, Crew was suddenly offered the post intended for Darbishire: that of director of a new Animal Breeding Research Station in Edinburgh. Despite his own concerns that he was scarcely qualified in genetics, Crew went on to develop the Station into the internationally renowned Institute of Animal Genetics.

At the end of a long career, Crew was able to reflect on the career which his harrowing war experiences had encouraged him to pursue: ‘I find great pleasure in the thought that those who stand on my shoulders will see much further than I did in my time. What more could any man want?’

Project Archivist, ‘Towards Dolly: Edinburgh, Roslin and the Birth of Modern Genetics’