SINKINGS AND LOSS OF LIFE, SHORTAGES OF SUPPLY, AND REQUISITIONING… DIFFICULTIES FACED BY THE FIRM OF CHRISTIAN SALVESEN & CO. DURING THE FIRST WORLD WAR

![]() Contemporary papers within the archive of the general shipping and whaling firm Christian Salvesen & Co. (Coll-36) – based in Leith, Scotland, until the late 20th century – tell of the company’s trials during the First World War. Indeed, diary entries of both Edward Theodore Salvesen (Lord Salvesen) (1857-1942) and a younger brother Theodore Emil Salvesen (1863-1942) record the loss of the Salvesen vessel Glitra which was the first British ship to be sunk through enemy action by a submarine in the opening months of the First World War. Glitra had been sunk by a German submarine on 20 October 1914, just off Skudenes, Rogaland, Norway.

Contemporary papers within the archive of the general shipping and whaling firm Christian Salvesen & Co. (Coll-36) – based in Leith, Scotland, until the late 20th century – tell of the company’s trials during the First World War. Indeed, diary entries of both Edward Theodore Salvesen (Lord Salvesen) (1857-1942) and a younger brother Theodore Emil Salvesen (1863-1942) record the loss of the Salvesen vessel Glitra which was the first British ship to be sunk through enemy action by a submarine in the opening months of the First World War. Glitra had been sunk by a German submarine on 20 October 1914, just off Skudenes, Rogaland, Norway.

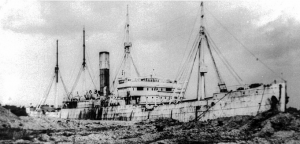

The Salvesen vessel ‘Glitra’ scuttled by its German captors off Skudenes, Norway 20 October 1914. Coll-36 (2nd tranche, C1. No.41).

Glitra had started life as the Saxon Prince at the Swan Hunter yard on the Tyne (Wallsend) where it was launched in 1882. It sailed with the Prince Steam Shipping Co. until 1895 when it was acquired by Christian Salvesen & Co. and renamed Glitra. During a voyage from Grangemouth to Stavanger in Norway, carrying coal, iron plate and oil, the ship was stopped and searched 26 km off Skudenes – just outside neutral Norwegian territorial waters – by the German U-boat U-17 commanded by Kapitänleutnant Johannes Feldkirchner.

Diary entry of Lord Salvesen noting the loss of ‘Glitra’ in October 1914. Salvesen Archive. Coll-36 (1st tranche, Diaries of Lord Salvesen, F17).

No lives were lost during the incident however, as the crew of the Glitra had been ordered into lifeboats . The German sailors then opened the ship’s sea-valves and scuttled it. After U-17 left the scene, the torpedo boat Hai of the Royal Norwegian Navy took the lifeboats under tow to the Norwegian harbour of Skudeneshavn. The same U-boat, U-17, captured and sunk the Salvesen vessel Ailsa just north-east of Bell Rock in the North Sea on 17 June 1915.

Diary entry of Theodore Emil Salvesen noting the loss of ‘Glitra’ in October 1914. Salvesen Archive. Coll-36 (1st tranche, Diaries of Theodore Emil Salvesen, F42).

The Glitra incident was recorded in the diaries of both Lord Salvesen and Theodore Emil Salvesen. About the loss, the elder Salvesen brother wrote on Wednesday 21 October 1914, ‘Sad news that Glitra captured by German submarine & sunk’. The younger Salvesen – perhaps still recovering from the bout of bronchitis which he also noted in his diary – wrote his own stark and matter-of-fact entry on Tuesday 20 October, ‘Glitra S/S sunk off Norway’, and about the loss of Ailsa in 1915 his diary entry for Friday 18 June 1915 has ‘Ailsa S/S reported sunk by submarine yesterday off Bell Rock. 40 miles’.

The Salvesen cargo ship ‘Coronda’ torpedoed by German submarine ‘U-81’ in the Atlantic Ocean 200 miles off Ireland, 13 March 1917. Coll-36 (2nd tranche, C1. No.41).

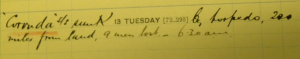

Although the scuttling of the Glitra was the first instance of a British merchant vessel being lost to a German submarine, Salvesen would face the loss of several other vessels from its general cargo fleet during the First World War, not least the 2733 ton cargo ship Coronda which was torpedoed by U-81 in the Atlantic Ocean 330 km west of Donegal, Ireland, on 13 March 1917, with the loss of nine lives. Again, the incident was recorded in briefest terms by Theodore Emil Salvesen in his diary, ‘Coronda S/S sunk by torpedo, 200 miles from land, 9 men lost – 6.30am’. The names of some of the lost Salvesen ships – e.g. Glitra, Ailsa and Coronda – would be preserved in newer vessels a few years later.

Diary entry of Theodore Emil Salvesen noting the loss of ‘Ailsa’ in June 1915. Salvesen Archive. Coll-36 (1st tranche, Diaries of Theodore Emil Salvesen, F42).

Diary entry of Theodore Emil Salvesen noting the loss of ‘Coronda’ in March 1917. Salvesen Archive. Coll-36 (1st tranche, Diaries of Theodore Emil Salvesen, F42).

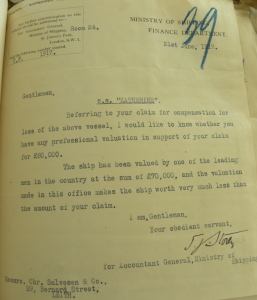

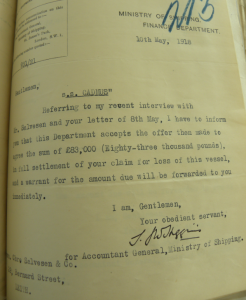

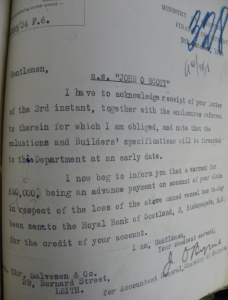

A little earlier, in February 1917, the Salvesen vessel Katherine was captured and sunk by the German merchant raider SMS Möwe . A letter from the Finance Department of the Ministry of Shipping in London to Christian Salvesen & Co. in Leith, dated 21 June 1917, reveals that the Government department was unwilling to accept the claim of £80,000 placed before them by the firm for their loss and sought ‘professional valuation in support’ of the claim. The letter stated that the vessel ‘has been valued by one of the leading men in the country at the sum of £70,000, and the valuation made in this office makes the ship worth very much less than the amount of your claim’. Later, in July 1917, the Ministry of Shipping would offer £75,000 to the firm. In March 1918 there would be further objection from the Ministry over the claim placed by Christian Salvesen & Co. for the loss of the vessel Cadmus which had been torpedoed and sunk off Flamborough Head in October 1917 by the German mine-laying submarine UC-47. The Ministry would eventually agree the sum of £83,000 in full settlement of the firm’s claim for the loss of Cadmus, and in November 1918 the Ministry agreed to pay £40,000 to Salvesen for the loss of the John O. Scott which had been torpedoed and sunk off Trevose Head, Cornwall, in September 1918 by the German mine-laying submarine U-117.

Letter from the Ministry of Shipping to Christian Salvesen & Co., dated 21 June 1917, about the firm’s claim for the loss of the vessel ‘Katherine’ through enemy action. Salvesen Archive. Coll-36 (1st tranche, Letter book, A77).

Letter from the Ministry of Shipping to Christian Salvesen & Co., dated 10 May 1918, about the firm’s claim for the loss of the vessel ‘Cadmus’ through enemy action. Salvesen Archive. Coll-36 (1st tranche, Letter book, A77).

Letter from the Ministry of Shipping to Christian Salvesen & Co., dated 4 November 1918, about the firm’s claim for the loss of the vessel ‘John O. Scott’ through enemy action. Salvesen Archive. Coll-36 (1st tranche, Letter book, A77).

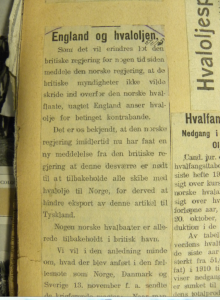

In spite of the loss of cargo vessel tonnage, the other arm of the company’s business – whaling in the South Atlantic around South Georgia – expanded further to supply much needed whale oil for the home front. The oil was required to make glycerol for the manufacture of nitro-glycerine for explosives. Whale oil was also used for the production of edible fat. To all nations – whaling or non-whaling, belligerent or neutral – the commodity was a vital one. Indeed, recorded in a collection of newspaper-cuttings within the archive of Christian Salvesen & Co. is a small article reporting a protest from Norway over the impounding of Norwegian ships and whale-oil cargo in British ports… clearly breaches of the country’s neutrality by Britain. The article reports how previously the British authorities had notified Norway that they would respect the Norwegian whaling fleet, except in cases where it was believed the cargo was being supplied to Germany. Now however, the article continues, the Norwegian government had received a new message from the British government indicating that it was forced to impound all Norwegian ships with whale-oil cargoes to prevent export to Germany. Some Norwegian ships had already been impounded. The article goes on to remind the British governement of the rights of neutral states such as Norway, Denmark and Sweden to onward transport of cargoes and free navigation.

Article, ‘England og hvaloljen’, dated 5 January 1915, from Norwegian title (unknown) reporting change in British policy towards Norwegian ships and cargoes. Salvesen Archive. Coll-36 (1st tranche, News-cutting Album, H27).

To increase whale oil production as the War continued, all regulations around the whaling-industry were relaxed including restrictions on the number of whale-catching vessels. Nevertheless, shortages at home in the northern hemisphere due to the war economy, and loss of the island nation’s valuable imports and exports through enemy action, affected the firm’s activities in the southern hemisphere, and the supply to it of the necessary resources to maintain its operations. Indeed, everything from fuel oils and coal, prefabricated buildings, machine tools, wires and cables, tanks, saws and saw blades, timber and wood products, and food provisions all had to be sourced beyond South Georgia and the Falkland Islands.

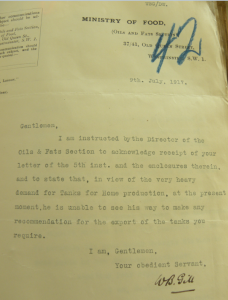

Letter from the Ministry of Food, Oils and Fats Section, to Christian Salvesen & Co., dated 9 July 1917, about the export of tanks. Salvesen Archive. Coll-36 (1st tranche, Letter book, A77).

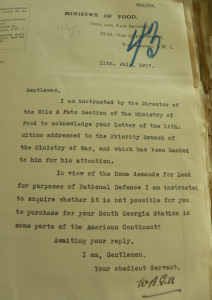

The UK was often unable to supply the resources. On 9 July 1917, the Oils and Fats Section of the Ministry of Food wrote to Christian Salvesen & Co. stating that ‘in view of the very heavy demand for Tanks for Home production’ the Director was ‘unable to see his way to make any recommendation for the export of the tanks’ required. A couple of days later, on 11 July 1917, the same Oils and Fats Section at the Ministry of Food wrote that ‘In view of Home demands for Lead for purposes of National Defence I am instructed to enquire whether it is not possible for you to purchase for your South Georgia Station in some parts of the American Continent?’

Letter from the Ministry of Food, Oils and Fats Section, to Christian Salvesen & Co., dated 11 July 1917, about lead and the possibility of obtaining the resource from the Americas. Salvesen Archive. Coll-36 (1st tranche, Letter book, A77).

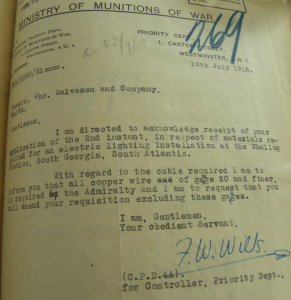

Again, on 19 July 1918, but this time from the Ministry of Munitions of War, came a letter to Christian Salvesen & Co. acknowledging receipt of an application ‘in respect of materials required for an electric lighting installation at the Whaling Station, South Georgia’. With regard to the cabling required, the Ministry wrote that ‘all copper wire of gauge 20 and finer, is required by the Admiralty’.

Letter from the Ministry of Munitions of War, to Christian Salvesen & Co., dated 19 July 1918, about Admiralty expropriation of copper wire of gauge 20 and finer. Salvesen Archive. Coll-36 (1st tranche, Letter book, A77).

Although there was a demand for whale-oil throughout the War (for glycerol and the subsequent manufacture of nitro-glycerine for explosives), it is clear that shortages of equipment and government restrictions were making it extremely difficult for the firm to meet the demand. Indeed, plans to increase the number of steam-powered whale-catching vessels operating in the Southern Ocean had to be abandoned.

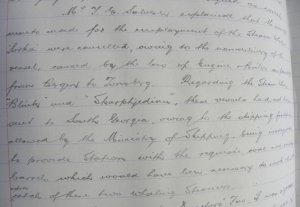

Extract from the Minutes of a Meeting of Directors (South Georgia Co. Ltd) held Thursday 26 July 1917 in Leith, and during which hiring of additional steam-powered whale-catchers was discussed. Coll-36 (3rd tranche, Minute Book, South Georgia Co. Ltd).

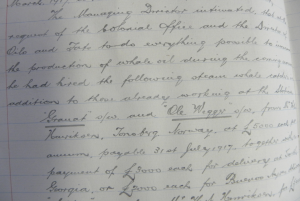

At a meeting of Salvesen Directors (The South Georgia Company Ltd) held at the Registered Office in Bernard Street, Leith, on 26 July 1917, it was agreed that in order ‘to do everything possible to increase the production of whale oil during the coming season’ the vessels Granat, Ole Wegger, and Sorka would be hired from Norway, and Blink and Skarphjedinn from Cape Town. In the event, Sorka had to be retained in Norway because of local losses of tonnage, and neither the vessel Blink nor Skarphjedinn could be sent south because restrictions put in place by the Ministry of Shipping meant that the station there could not be provided ‘with the requisite coal and empty barrels which would have been necessary to work up the extra catch of these whaling steamers’.

Extract from the Minutes of a Meeting of Directors (South Georgia Co. Ltd) held Friday 21 June 1918 in Leith, and during which failure to hire additional steam-powered whale-catchers was discussed. Coll-36 (3rd tranche, Minute Book, South Georgia Co. Ltd).

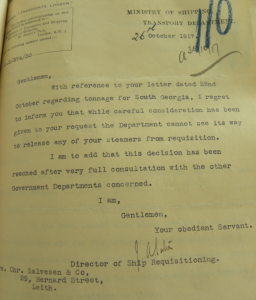

Like other shipping firms in ports around the UK, Christian Salvesen & Co. had many of its vessels requisitioned by the Government – and subsequently sunk by the Germans. This of course impacted on its South Georgia operations and its own means of supplying and maintaining these operations. A letter from the Director of Ship Requisitioning at the Transport Department of the Ministry of Shipping in London, dated 26 October 1917, records the firm’s anxieties about requisitioning. The letter in reply states that ‘regarding tonnage for South Georgia, I regret to inform you that while careful consideration has been given to your request the Department cannot see its way to release any of your steamers from requisition’.

Letter from the Ministry of Shipping, to Christian Salvesen & Co., dated 26 October 1917, about a request for the release of vessels from requisition. Salvesen Archive. Coll-36 (1st tranche, Letter book, A77).

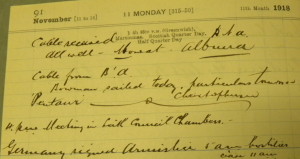

At 5am on the morning of Monday 11 November 1918 – as noted in the diary entry of Theodore Emil Salvesen – Germany signed the Armistice agreement, and hostilities were to cease at 11am. The slaughter of the Great War was over.

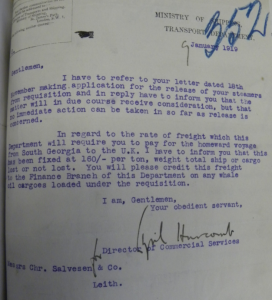

In January 1919, some two months after the Armistice, the office of the Director of Commercial Services at the Ministry of Shipping wrote to Christian Salvesen & Co. about the firm’s ‘application for the release’ of its steamers from requisition. This matter, wrote the Ministry, ‘will in due course receive consideration’, but ‘no immediate action can be taken in so far as release is concerned’.

Letter from the Ministry of Shipping, to Christian Salvesen & Co., dated 9 January 1919, about the release of vessels from requisition. Salvesen Archive. Coll-36 (1st tranche, Letter book, A77).

Following the War came Peace and the firm of Christian Salvesen & Co. took advantage of the increased demand – and of course high prices – for ships and sold off a large part of its fleet. This would help keep the company afloat during the years of economic crisis that would come in the late-1920s and into the 1930s.

Diary entry of Theodore Emil Salvesen for Monday 11 November 1918, noting the Armistice. Salvesen Archive. Coll-36 (1st tranche, Diaries of Theodore Emil Salvesen, F42).

Dr. Graeme D. Eddie, Assistant Librarian Archives & Manuscripts, Centre for Research Collections

In addition to material in the Archive itself, and on-line maritime wreck sites, the following work was used in the construction of the blogpost: Salvesen of Leith, by Wray Vamplew (Scottish Academic Press: Edinburgh, London, 1975)