Home University of Edinburgh Library Essentials

February 24, 2026

D-Day anniversary: Norman memories in the archives

A more personal take on our archives…

As any archivist knows, you can sometimes stumble upon archives with an unexpected and personal connection: this was the case for me when I found out that in the Special Collections of the Library was an album containing 175 photographs and postcards showing my home city, Caen, before and during the Second World War (Coll-164)… It immediately reminded me of my own grandparents, who had lived through the occupation, the bombing and finally the liberation of this medium-sized Norman city. They would always tell me stories about life during the war, and describe the way Caen looked before it: indeed, about 80 percent of the city was destroyed, in particular during the controversial bombing raid that preceded the ‘Operation Charnwood’ in July 1944.

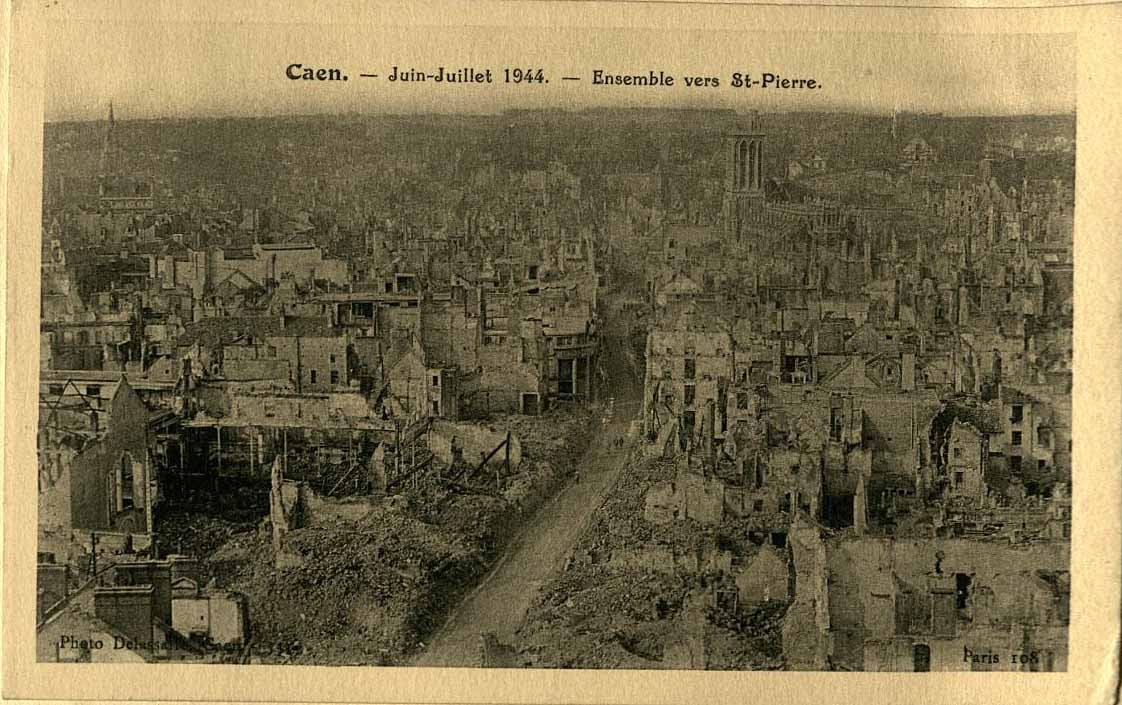

Aerial view of Caen after the bombings in July 1944 (Coll-164/4)

As you can see in the picture, the city was ravaged. The central area around the castle, St Pierre Church, and the neighbourhood called îlot St Jean were particularly affected. Post-war Caen looks like a field of ruins, and I was moved when I browsed the album for the first time and saw the full extent of the devastation. When it happened my grandmother, who was around 15 at the time, had taken shelter in a town a few kilometres away; but my grandfather was there and took part in the rescue effort to help searching the rubbles for survivors. He was only 18.

Looking through the album, I was able to recognise a few familiar buildings amid the destruction: churches, streets, houses, the castle… I knew exactly where these were and what they looked like now. I found the comparison really interesting, and this is why I decided to do a little before/after photo shoot when I went home for the Christmas holidays.

St Pierre Church and surrounding area (Coll-164/58)

I started my little project on a sunny winter afternoon. Walking past my old university, I remembered that one of the nearby avenues was called ‘Avenue d’Edimbourg‘; and I finally understood why! Edinburgh was one of the cities that sent help and supplies to Caen after the bombing raid. The album is testimony to this connection: it was donated by John Orr, Professor of French at the University of Edinburgh and founder of the Caen-Edinburgh Fellowship. The latter was set up after the war to help the inhabitants of Caen by sending food, clothes, and supplies to the devastated city. John Orr himself organised for books to be sent to the library of the University, which was completely destroyed and had to be rebuilt from scratch, and for this he’s also had a street named after him.

Street signs named after John Orr.

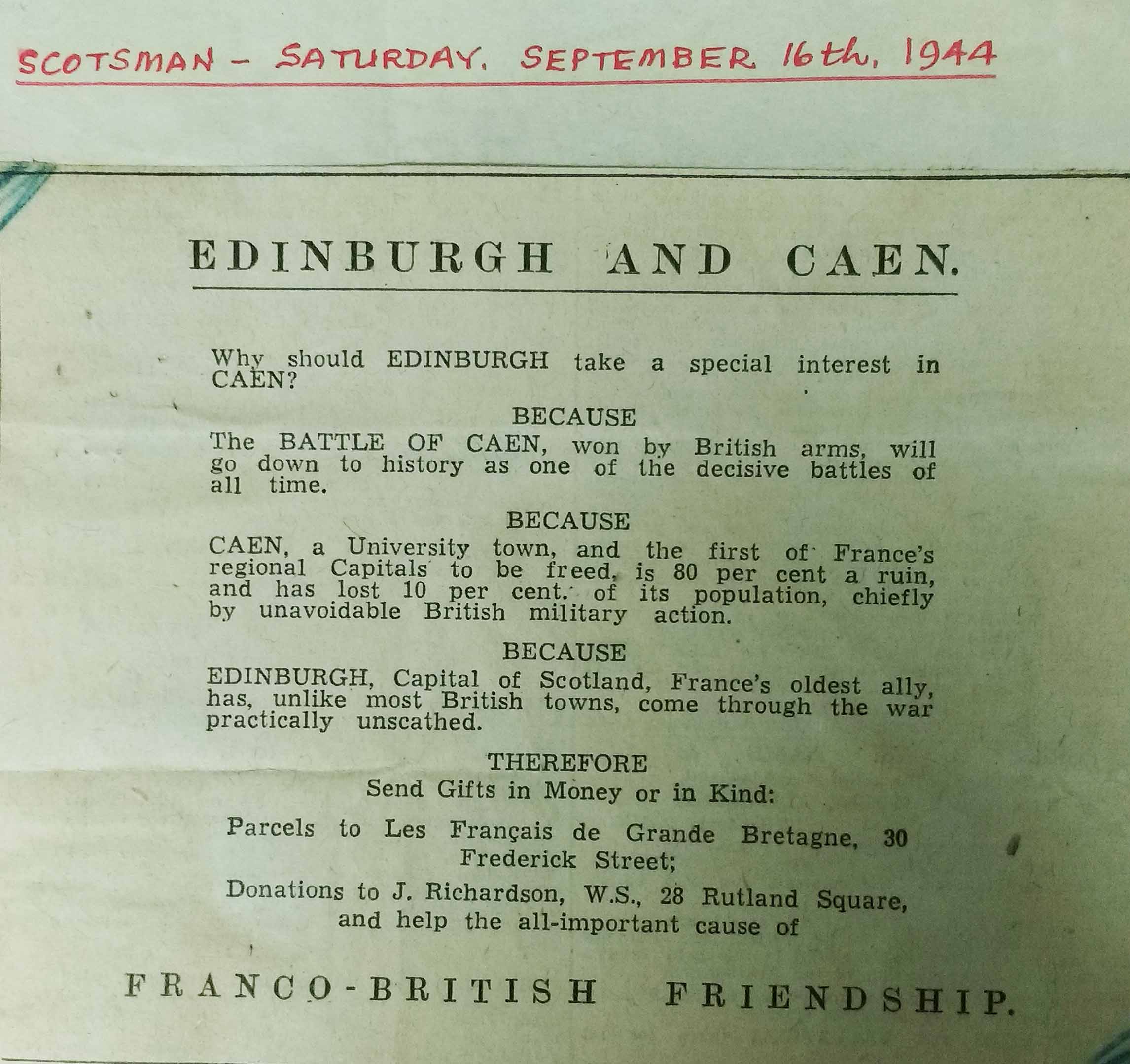

Call for donations to Caen from the papers of Professor John Orr held in the Special Collections (Coll-77).

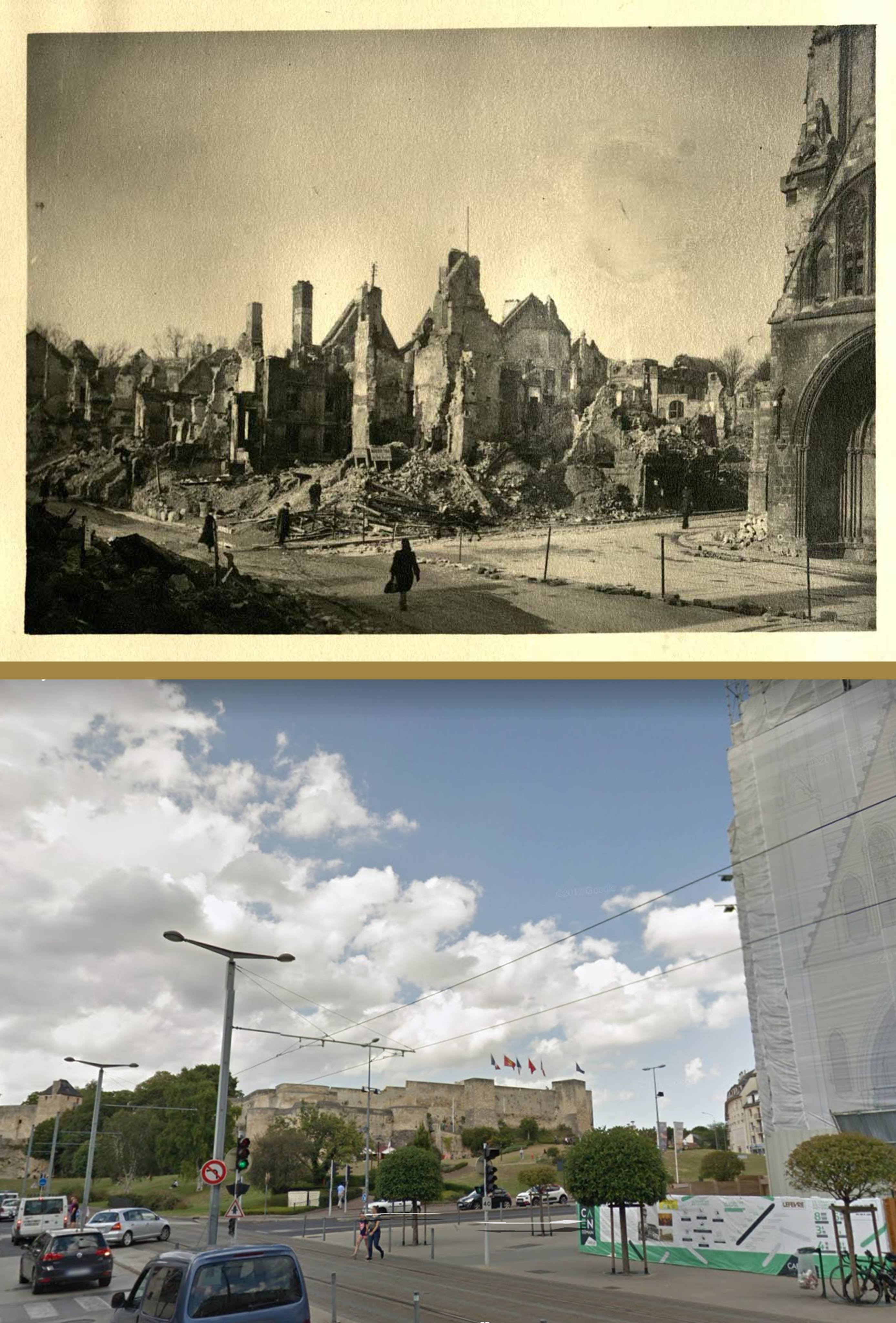

I soon arrived in the city centre. The most noticeable building in Caen is its massive castle, founded in 1060 by William the Conqueror. It was used as barracks between 1789 and 1945, and occupied by German troops during the War, which explains why it was targeted by bombings. Some buildings and parts of walls were damaged, but most of it survived in decent condition. The same cannot be said for the houses build alongside its walls…And so, after the clearing of the ruins, the castle reappeared, and it was decided to restore and showcase this millennium-old building that overlooks the city. The words of my grandmother came back to me: ‘We didn’t even know we had a castle because there were so many houses around it! After the war it came a bit as a surprise…’

Castle of Caen seen from St Pierre Church. The surrounding buildings which were hiding it for centuries were not rebuilt after the war. (Coll-164/61)

Maison des Quatrans. The buildings which were in-between the house and the castle have been destroyed. (Coll-164/71)

But not everything was completely destroyed in Caen! Our old town centre, the Quartier St-Pierre (‘St Pierre neighbourhood’), still has many original features. The Church, for starter – the tower was destroyed and then rebuilt, and is now being cleaned to restore its original white-yellowish colour, darkened by pollution. The buildings around it, however, went up in smoke. La Rue Montoire Poissonerie (Montoire Poissonerie Street), for example, has vanished.

St Pierre Church from Rue Montoire Poissonerie (now an apartment building). (Coll-164/11)

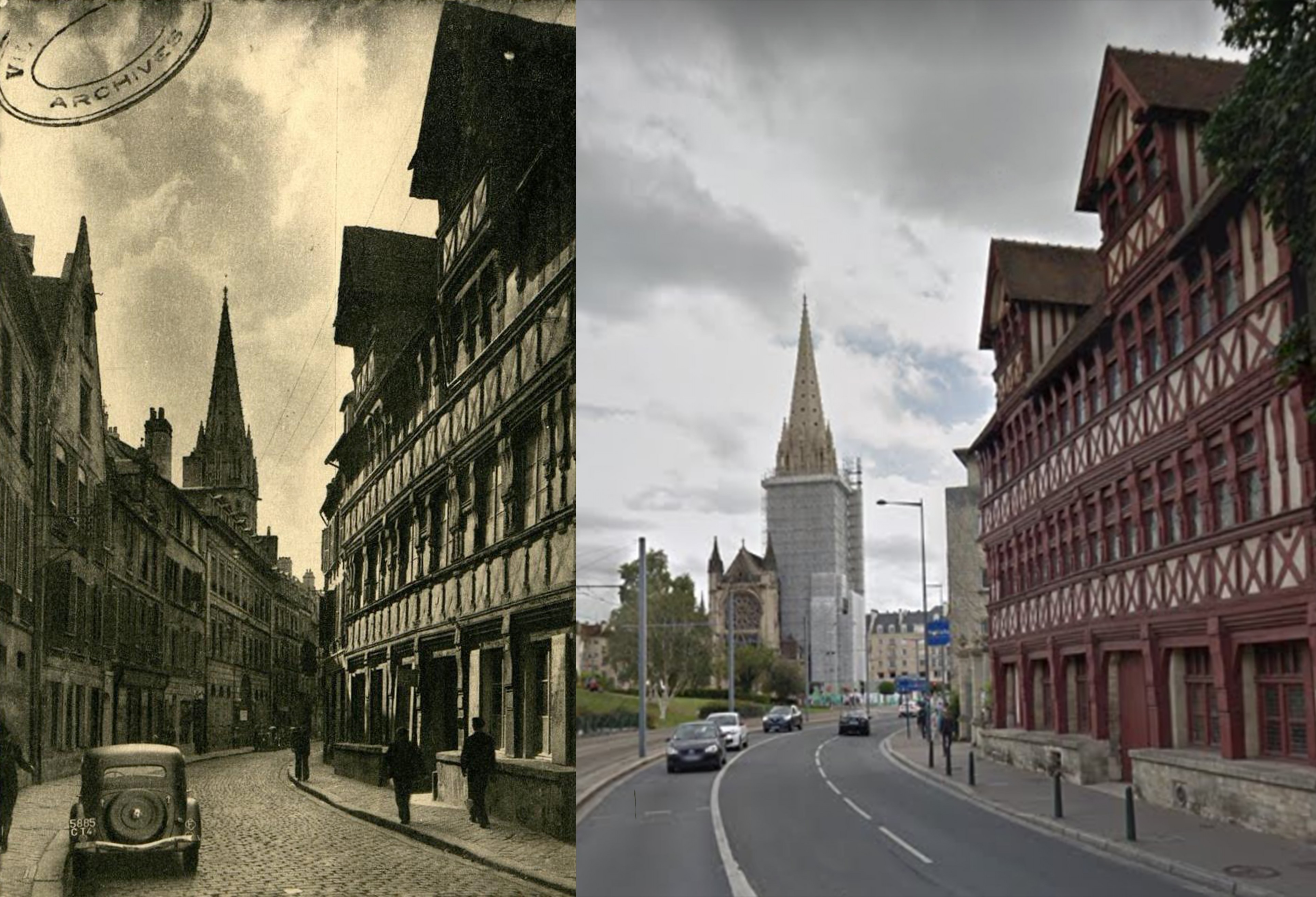

On the other hand, the main street of the neighbourhood, la rue St Pierre, has been more or less spared, and the old stands alongside the new. In the picture below you can see the busy Place St Pierre, full of shoppers and tourists, with the church Notre-Dame-de-Froide-Rue in the background and a beautiful half-timbered house from the 15th century. They miraculously survived, and are now being restored to get their lively colours back!

Place St Pierre and its 15th century half-timbered houses. (Coll-164/18)

Place St Pierre and Notre-Dame-de-Froide-Rue Church. (Coll-164/38)

As a medievalist, I still regret the loss of the Rue St Jean, a once beautiful street full of hôtels particuliers and ancient half-timbered houses just like the one in the picture above. One of the only original buildings still standing is the very curious Eglise Saint-Jean – which has the particularity of being completely wonky! Our very own modest Pisa Tower, which is leaning because Caen was built on unstable grounds. Everybody thought this fragile building would never last – little did they know it would be the only monument to survive the raid of St-Jean street.

Eglise Saint-Jean, which is much sturdier than it looks…(Coll-164/72)

Sometimes, there was nothing to save but a section of wall, a half-collapsed doorway, the base of a pillar…left as a memory, a reminder of what the city had gone through:

Saint-Gilles Church, now a small park. The only recognisable feature is an archway. (Coll-164/36)

Saint-Julien Church before, during and after the bombings. (Coll-164/45 and Coll-164/48)

Like many French towns and cities, old Caen was full of narrow, dark medieval streets that would add a lot of charm to a city nowadays. I remember lamenting about the destruction of these quaint quarters – some of the largest boulevards in Caen have actually been shaped by American bulldozers –, and my grandfather replying: ‘it was dark and dirty before, very cold and inconvenient. It’s nicer now. They did a good job rebuilding everything’. The inhabitants rebuilt their home with the very typical Caen stone, which has a light and warm yellow colour, and the new blends in with the old. The city may not be as beautiful as other French towns spared by the war, but it is a nice place to live, where history has left its mark.

Our archivist doing some fieldwork…

Description of the album on ArchivesSpace: https://archives.collections.ed.ac.uk/repositories/2/resources/312

Aline Brodin, cataloguing archivist, 6 June 2018.

Special thanks to Clément Guézais and Inès Prat for their help in taking and editing the photographs.

Defence, Duress, and Detectives: Alexander McCall Smith’s PhD

Most know the name of Alexander McCall Smith in connection with his award-winning children’s literature, but he is also a giant in the legal field, both in the UK and in southern Africa where he was born. He was co-founder of the law school at the University of Botswana, and today he holds the title of Emeritus Professor of Medical Law at the University of Edinburgh. But bearing in mind that he is also the author of novels which have been read by millions, it’s easy to see the twinkle of a novelist behind his engaging style of legalese, and vice versa:

“Hugh spoke triumphantly. ‘Then your position is even stronger! … It’s a promise extracted under duress. He’s ground you down — taken advantage of you; pushed you into making the offer.’”

This passage from A Conspiracy of Friends (2011, first serialized in The Scotsman) was written nearly 30 years after McCall Smith submitted his PhD thesis, The Defence of Duress, to the faculty of law at the University of Edinburgh, which marked the beginning of an influential legal career. This thesis, which came under our scanners in April, provides a unique glimpse at the background of a writer who enjoyed success in two very different careers.

His PhD thesis attempts to give some scope to the depth of complexities beneath simple questions: “How is coercion to be distinguished from influence or persuasion? Is coercion inevitably a moral concept? Is an agent who performs an act under coercion always to be relieved of responsibility for his action?” McCall Smith takes nothing for granted as he picks apart the fibres of legal principles so old and venerable they were no longer questioned.

He begins the argument by harkening back to Aristotle’s explorations on the subject.

He begins the argument by harkening back to Aristotle’s explorations on the subject.

McCall Smith approves of the ‘lenient’ attitude of modern law toward crimes committed under duress, while supporting the view that “the moral gravity of the act performed under compulsion is relevant in assessing responsibility for compelled action, as is the degree of compelling force used.”

Philosophical abstractions are accompanied by illustrative examples, such as:

In the end, he finds, there are two logical approaches toward the question of culpability in these scenarios, and each in some measure absolves the victim-cum-perpetrator:

McCall Smith’s fictional works have been praised for depicting complex truths within the simple actions required to live, and it’s easy to see how a legal background could add colour to this way of seeing the world. His books, mainly written for young adults, far from being sugar-coated or dumbed down, are complex discussions of ethical problems. Similarly we see in his legal ruminations an articulate relevance to everyday moral dilemmas. Reading this thesis, which he wrote at the age of 31, we can see a storyteller beneath the barrister’s wig — in fact he published his first book, The White Hippo, less than a year after receiving his diploma from Edinburgh.

In an interview in 2004, McCall Smith stated:

“In my books I’m increasingly going to look at that question: how people resolve ordinary dilemmas and moral issues in their day-to-day life.” (Interview in The New York Times, 6 October 2004)

I enjoyed reading this thesis, but I’ve also taken the opportunity to re-acquaint myself with the powerful and charming novels which came after it.

McCall Smith’s PhD thesis, The Defence of Duress, was digitized in April by the Centre for Research Collection’s ongoing digitization project and can be downloaded from the Edinburgh Research Archive: https://www.era.lib.ed.ac.uk/handle/1842/30464

Gavin Willow, Project Digitisation Assistant, PhD Digitisation Project

Database trial – Ogonek Digital Archive 1923 – 2017

The Library has arranged a free trial of Ogonek Digital Arch ive 1923 – 2017 until 29 June 2018. The trial can be access on the University network via the web link: http://dlib.eastview.com/browse/udb/3030

ive 1923 – 2017 until 29 June 2018. The trial can be access on the University network via the web link: http://dlib.eastview.com/browse/udb/3030

Ogonek is one of the oldest weekly magazines in Russia, having been in continuous publication since 1923. The importance of Ogonek as a primary source for research into the Soviet Union and bolshevization of its cultural and social landscapes cannot be overestimated. The digital archive provides access to fully searchable full-text and full-colour digital copies of issues of Ogonek from 1923 through 2017.

On trial: Scottish nationalist leaflets, 1844-1973

*The Library has now purchased access to ‘Scottish nationalist leaflets, 1844-1973’. See New to the Library: Scottish nationalist leaflets, 1844-1973.*

I’m pleased to let you know that thanks to a request from a student in HCA the Library now has trial access to Scottish nationalist leaflets, 1844-1973 from British Online Archives. This primary source collects together pamphlets relating to Scottish nationalism printed by the Scottish National Party (SNP) and their predecessors.

You can access this online resource via the E-resources trials page.

Access is available both on and off-campus.

Trial access ends 4th July 2018.

Read More

New to the Library: Irish Newspaper Archive

I’m very happy to let you know that following a successful trial earlier this year and further to requests from students and staff in HCA the Library has a 1-year subscription to the Irish Newspaper Archive. This is the largest online database of Irish newspapers in the world covering nearly 300 years worth of history.

You can access the Irish Newspaper Archive via the Databases A-Z list or Newspapers and Magazines database list. You will soon also be able to access it via DiscoverEd. Access on-campus is direct but if you are working off-campus you will need to use VPN to get access. Read More

Times Higher Education – now available

University of Edinburgh current staff and students now have access to the Times Higher Education via a library subscription.

University of Edinburgh current staff and students now have access to the Times Higher Education via a library subscription.

With our institutional subscription, you will be able to read online articles and digital editions using the THE website, and you will also be able to download the THE app to your device.

This service provides access to the latest weekly edition, and you can also access full text dating back to January 2013. An archive of earlier articles can be searched, and you have the option to set up a weekly email alerting you when the new edition is available.

Access is enabled via a personal account which is associated with the University using your official University e-mail address (ending .ed.ac.uk)

Registering as a first time user

You can register for an account to access our institutional subscription from 1st June onwards.

If you are registering to access the Times Higher Education for the first time please follow these instructions so that your personal THE account is associated with the University’s institutional subscription:

- From the Times Higher Education website click on the user account icon (i.e. the red person icon towards the top right)

- Register using your University of Edinburgh email address ending @ed.ac.uk

- Choose a username and password (please note that your username will appear in public facing parts of the site – for example if you choose to leave comments on articles)

- Click on Join us at the bottom and you will be logged in

- You will receive a confirmation email

Once you have successfully registered your personal account, just click on Login the next time you use the service.

Access digital editions

- To access digital editions of Times Higher Education, go to the magazine’s homepage at https://www.timeshighereducation.com.

- Click the “Professional” tab, then click “Digital Editions”.

- Then simply select the issue you want to view.

Download the app

- The Times Higher Education app is available on iOS, Android and Kindle Fire. Visit your app store provider to download it to your device.

- Select the edition you would like to view (e.g. UK or Global).

- Log in by clicking on the icon in the top right corner.

- Select Account, then click “Existing THE account”.

- Enter your username and password.

Still need help?

If you require further information about setting up your access for the library subscription to Times Higher Education then please:

Contact us via the IS Helpline

IIIF Conference, Washington, May 2018

Washington Monument & Reflecting Pool

We (Joe Marshall (Head of Special Collections) and Scott Renton (Library Digital Development)) visited Washington DC for the IIIF Conference from 21st-25th May. This was a great opportunity for L&UC, not only to visit the Library of Congress- the mecca of our industry in some ways- but also to come back with a wealth of knowledge which we could use to inform how we operate.

Edinburgh gave two papers- the two of us delivering a talk on Special Collections discovery at the Library and how IIIF could make it all more comprehensible (including the Mahabharata Scroll), and Scott spoke with Terry Brady of Georgetown University showing how IIIF has improved our respective repository workflows.

From a purely practical level, it was great to meet face to face with colleagues from across the world- we have a very real example of a problem solved with Drake from LUNA, which we hope to be able to show very soon. It was also interesting to see how the API specs are developing- the presentation API will be enhanced with AV in version 3, and we can already see some use cases with which to try this out; search and discovery are APIs we’ve done nothing with, but these will help the ability to search within and across items, which is essential to our estate of systems, and 3D, while not having an API of its own, is also being addressed by IIIF, and it was fascinating to see the work that Universal Viewer and Sketchfab (which the DIU use) are doing to accommodate it.

The community groups are growing too, and we hope to increase our involvement with some of the less technical areas- Manuscripts, Museums, and the newly-proposed Archives group in the near future.

Among a wealth of great presentations, we’ve each identified one as our favourite:

Scott: Chifumi Nishioka – Kyoto University, Kiyonori Nagasaki – The University of Tokyo: Visualizing which parts of IIIF images are looked by users

This fascinating talk highlighted IIIF’s ability to work out which parts of an image, when zoomed in, are most popular. Often this is done by installing special tools such as eyetrackers, but the nature of IIIF- where the region is displayed as part of the URL- the same information can be visualised by interrogating Apache access logs. Chifumi and Kiyonori have been able to generate heatmaps of the most interesting regions on an item, and the code can be re-used if the logs can be supplied.

Joe: Kyle Rimkus – University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Christopher J. Prom – University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign: A Research Interface for Digital Records Using the IIIF Protocol

This talk showed the potential of IIIF in the context of digital preservation, providing large-scale public access to born-digital archive records without having to create exhaustive item-level metadata. The IIIF world is encouraging this kind of blue-sky thinking which is going to challenge many of our traditional professional assumptions and allow us to be more creative with collections projects.

It was a terrific trip, which has filled us with enthusiasm for pushing on with IIIF beyond its already significant place in our set-up.

Joe Marshall & Scott Renton

Library Of Congress Exhibition

EU copyright, quo vadis?

This month our copyright expert Eugen attended a one day conference in Brussels to keep up to date with the latest developments in Intellectual Property law. “EU copyright, quo vadis? From the EU copyright package to the challenges of Artificial Intelligence” was a one-day conference held at Université Saint-Louis in Brussels on 25th May 2018. It was organised by the European Copyright Society, which is a platform for critical and independent scholarly thinking on European Copyright Law and policy.

This month our copyright expert Eugen attended a one day conference in Brussels to keep up to date with the latest developments in Intellectual Property law. “EU copyright, quo vadis? From the EU copyright package to the challenges of Artificial Intelligence” was a one-day conference held at Université Saint-Louis in Brussels on 25th May 2018. It was organised by the European Copyright Society, which is a platform for critical and independent scholarly thinking on European Copyright Law and policy.

There were over 100 participants from almost every European country and almost every area where Intellectual Property has an important contribution: many academics and researchers, practitioners from law firms such as Allen & Overy, consultants from Deloitte, media companies such as Channel 4 Television, ARD or Google, collective societies as ZAiKS Poland and from law courts such as the Ghent Court of Appeal.

The morning session was focused on the ongoing reform of the EU Copyright, the directive proposal that will be debated in the EU Parliament on 21 June 2018. There were presentations (text & data mining, education & libraries, the newly created right for press publishers) by academics highlighting the improvements brought by this proposal and its numerous shortcomings followed by interesting debates between the audience and a group of officials from the European Commission (Copyright Unit I.2, DG CNECT) invited to explain their vision and defend their point of view. Despite this, the general opinion in the room was that the copyright landscape will be polarised between rights-holders, who’s position will be greatly strengthened and enhanced, and a strictly regulated ‘small island of free access’ limited to libraries and universities and not much in between. Some participants were so critical of this proposed directive that they label it as ‘not fit for purpose’.

In the afternoon, the speakers discussed about the looming challenges that Artificial Intelligence (AI) poses to various key notions of copyright therefore the debates were both dry and technical. One particularly interesting debate was about the (proposed) ownership of copyright in machine generated data. Some participants commented that from the point of view of the European car-manufacturers this will balance out the GDPR (which prevents them to use data generated by increasingly sophisticated automobiles) while also preventing overseas competitors to use this data when designing autonomous cars.

There was also a book launch – P.B. Hugenholtz (ed.), Copyright Reconstructed, 2018 (with contributions of five members of the European Copyright Society).

It was extremely interesting to hear the strengths and weaknesses of the forthcoming EU copyright directive and to have a fairly clear idea of what is to come. The conference being organised in Brussels (this year) ensured a wide participation which vigorously (and belatedly) tested the EU officials. It will definitely help if academics and organisations like European Copyright Society, as a part of the civil society, will be more involved in the EU legislative process.

Read all about it!

Read all about our ‘Evergreen: Patrick Geddes and the Environment in Equilibrium’ project news in our latest newsletter – out now! All the updates; international visitors; collection discoveries (see below); what we’ll be doing next, and even some statistics (for those of you that like that sort of thing)! We hope you enjoy it. Newsletter 2 – May 2018 Previous newsletters can be found on our Newsletters page

A cyanotype of unidentified plant within botany collections of the Papers of Sir Patrick Geddes held at the University of Strathclyde Archives and Special Collections (Ref: T-GED/18/6/5b)

Collections

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Projects

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....