Home University of Edinburgh Library Essentials

March 13, 2026

Mixed Methods Reviews

Most researchers have heard of and understand the needs of a systematic review (SR), however the concept of a mixed methods review (MMR) can be confusing. The types of questions students and researchers ask can include:

- Can I do this type of research?

- How do I combine the data?

- My quantitative and qualitative data are different – how do I make sense of this?

MMRs differ from the traditional model of SR as they aim to answer complex interventions and social policy type questions. They go beyond what works and look to highlight the complexity of what is happening, to explain why things make an impact and what may influence how an intervention works, offering context to interventions.

To answer such questions MMRs need to draw from both quantitative and qualitative material (Pearson et al, 2015), but this does not mean they cannot be systematic!

To be systematic they should demonstrate the same transparent and explicit approach that established SR methods require – so have a protocol, as well as detailed reporting of methods. There would need to be appraisal and analysis of the included literature. They would need to show a rigorous research process (Gough et al, 2017).

There are different review approaches included in this type of research, but it is important that the research question uses both qualitative and quantative data. If the research question does not then it may be better to use another type of review method. An overview of review types can be found in an article by Sutton et al (2019).

How the types of data are combined depends on the research objectives of the review.

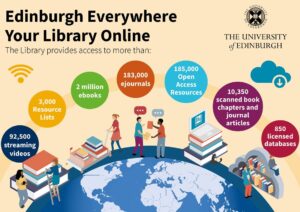

The resource SAGE Research Methods (which is available to all staff and students at the University via our Library Databases pages) has lots of information and advice on the ways that the differing data can be analysed and combined, as well as an overview of this family of research methodology.

Donna Watson

Academic Support Librarian

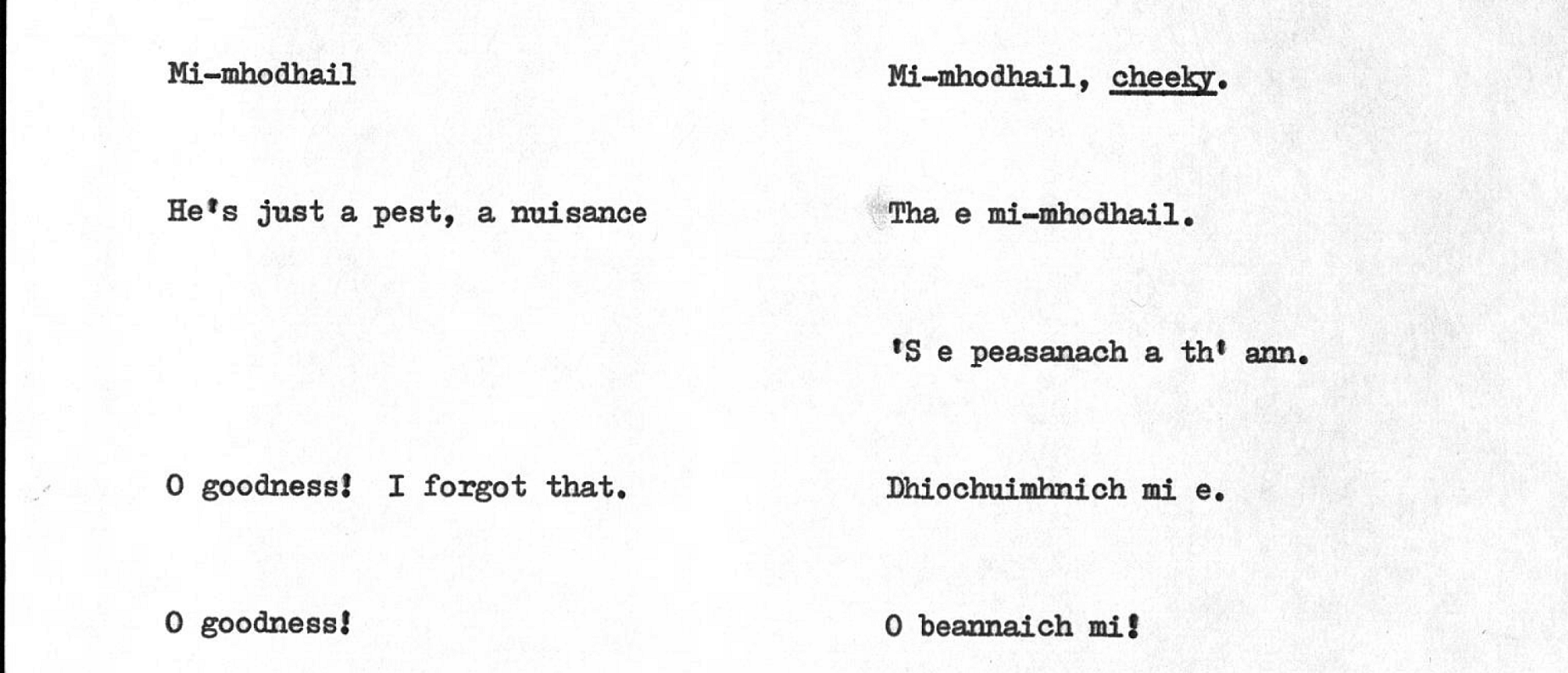

SSSA in 70 Objects: Linguistic Survey of Scotland: Gaelic grammar materials

By Dr Teàrlach Wilson

The first time I ever visited the SSSA, I was being given a tour by my supervisor to-be. I hadn’t officially submitted an application to do a PhD at the University of Edinburgh yet, but I had come up to Edinburgh from London to meet with my supervisor to-be, Dr Will Lamb, and to have an introductory tour of the University and the resources I hoped to work with. The SSSA was one of the reasons that attracted to me to Edinburgh. It was especially the moment that Will was showing me the Linguistic Survey of Scotland materials (collected between 1951 and 1963), and my eye was caught by a folder on which was written ‘St Kilda’. Anybody with an interest in Scottish history, culture, and identity will be fascinated by St Kilda, and there is often a nostalgia for what once was. As a linguist with a particular interest in geographical variation (‘dialects’), I was immediately excited and saddened by a very simple fact represented by the words ‘St Kilda’ on a document containing linguistic material: when a community ceases to exist, its special variety of speech also ceases to exist. The loss of the St Kilda dialect is not just a loss of localised language and cultural knowledge, it is also a reduction of the Scottish Gaelic language more generally. We have to be eternally grateful to the organisers and fieldworkers of the Linguistic Survey, or else this dialect – and others – could have been lost forever. We may never regain these dialects, but at least we have some idea of the linguistic patterns that existed within them. A great frustration for those studying linguistic variation is the lack of data available from previous periods of history, and it would be a great shame to have failed to collect this data in the 20th century when recording methods and technologies were available.

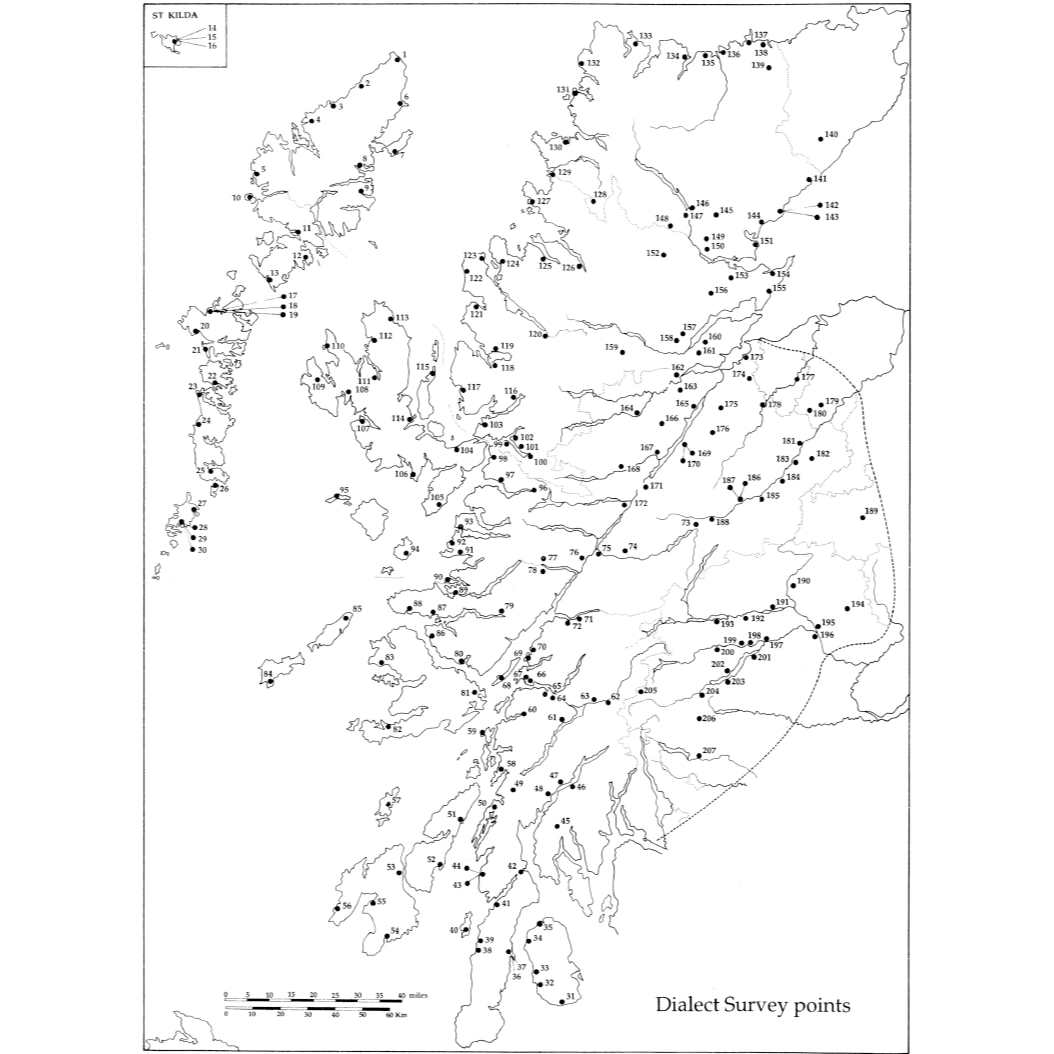

St Kilda isn’t, of course, the only ‘lost’ dialect to have been captured for posterity in the Linguistic Survey of Scotland. Another painful fact for those interested in Gaelic – be they linguists or from other disciplines – academic or not – is the generally northwesterly withdrawal of Gaelic across Scotland, so that the majority of mainland dialects are now obsolete and the Outer Hebrides are the last stronghold of the language. If you open the Linguistic Survey materials, or the only publication to come of the Linguistic Survey – ‘The Gaelic Dialects of Scotland’ (Ó Dochartaigh (ed.) 1997) – you will find this map of Scotland that represents the location of speakers who contributed their speech to the archive material:

Look at the geographic extent of the fieldwork activity! From as far north as Srathaidh (Strathy) in Sutherland to Sean-achaidh (Shannochie) at the most southerly tip of the Isle of Arran – and from as far west as Hiort (St Kilda) to Bràigh Mhàrr (Braemar) in Aberdeenshire – the entire Gàidheatachd (‘Gaelic-speaking region’) seems to be represented (except Loch Lomond, the Cowal peninsula, the Isle of Bute, and the south end of the Kintyre peninsula). By looking at this map and not looking at census data, you’d be forgiven for thinking that Gaelic was in a strong position – having so many speakers across the Scottish territory. However, the Linguistic Survey fieldworkers were also quite thorough in their note-taking and hints at the impending shift can be found in the notes that they took. On a number of occasions, fieldworkers talk about struggling to find speakers or note that the speakers have few, if any, fellow Gaelic speakers within their local social networks. Take into consideration that the majority of the contributors to the Survey were elderly (most being born in the 1880s), and you realise that the fieldworkers arrived at the cusp of a tipping point where traditional local Gaelic dialects go from ‘just holding on’ to ‘no longer existing’. Some fieldworkers even suggest that ‘linguistic decay’ (a term I absolutely loathe) is observable in the speech of those Gaelic speakers who represent the last speakers of their areas and who have perhaps not spoken Gaelic for years, even decades. The implication of this is that some of the material in the Survey don’t not, in fact, represent the traditional local dialects of some areas (Another term used is ‘linguistic attrition’, but I describe it as ‘contact-influenced change’ in my work to show that linguistic changes are natural and that ‘contact’ with the dominant language – English in our case – are driving some of those changes).

When I commenced my fieldwork – with the intention of comparing dialects of the Linguistic Survey with the dialects of speakers of a similarly elderly age today (who represent the grandchildren – or at least the grandchildren generation – of the contributors to the Survey), I found that the geographical extent of my fieldwork was going to be far more restricted than the range had by the fieldworkers who collected the Survey data around 60 to 70 years ago. Imagine the excitement of seeing historical linguistic forms mixed with an overwhelming sadness that they are lost. The emotions were, and still are, sometimes debilitating. I’d be looking at materials in the SSSA, with people around me in silence also looking at materials, and the rollercoaster of emotions would go from wanting to scream, “WOW!” to wanting to cry. I’m sure I wasn’t alone. There is sometimes a melancholy in the SSSA (which should never put you off going there) because visitors and researchers are all feeling the pain of loss – a loss that was so unnecessary. Sometimes you did not speak to fellow visitors or researchers, and so you had no idea what they were looking at or that they were feeling loss. Yet you still sometimes knew. As though a united purpose of capturing loss and criticising the unnecessary causes of loss was reverberating around the building. As I said: don’t let the melancholy put you off – it is a form of human bonding and communication. And that silent bonding is sometimes the most powerful.

It should go without saying that it’s not always melancholy. As I said, there are some moments of almost extreme excitement. One of the things that I enjoyed most about my research was finding contributors to my fieldwork who remembered or were related to contributors to the Linguistic Survey in the 1950s and 1960s. Reading fieldworkers’ notes about people – probably based on short experiences with the people and making assumptions sometimes driven by the fieldworkers’ own assumptions – and hearing stories about the same people from their neighbours and descendants made my cheeks hurt from smiling so much. Seeing a name written in the Survey and then asking a contributor, “did you know X?”, which then led to information not recorded in the Survey was like finding a precious treasure trove – the dialectological equivalent of finding Tutankhamun’s tomb. The similarities or differences between the accounts of people’s personalities and type of Gaelic was always amusing. I remember in particular one fieldworker noting how a female contributor had been quite conservative – almost archaic – in her use of Gaelic grammar, and then a neighbour of this woman (who must have died some half a century ago) recounting how forced her Gaelic sometimes seemed, how pious she was, and how miserable she was! She’d apparently often come to the door as she saw people passing her bothy on her croft just to lament at the state of the world! Something not noted in the fieldworker’s accounts, but you could certainly sense that it was the same woman! Maybe the fieldworker hadn’t been around long enough to witness her lamentations, or maybe she was on her best behaviour with the fieldworker, or the fieldworker wasn’t a member of her close social network. Nonetheless, the fieldworker’s comments about her Gaelic being old-fashioned made me think as I heard stories about her, “yes, it makes sense that someone like that would have some very old-fashioned speech!”

My fieldwork ended up being restricted to the Hebrides – both Inner and Outer. I went to the most northerly inhabited point of the Hebrides (Nis, Leòdhas, or Ness, Lewis in English) and to one of the most southerly (Port na h-Abhainne, Ìle, or Portnahaven, Islay). It was not easy to find contributors and my fieldwork is not as exhaustive as the Linguistic Survey. But combining Archive research with fieldwork in rural island communities has certainly been one of the most enriching experiences of my life, that has really informed who I am today and helped me develop my views and feelings about rural island communities, minority languages, and the importance of cultural – tangible and intangible – in a post-colonial, urban-centric, and land-facing society. I didn’t look at these people’s contributions to Lowland life, but make no mistake about it: rural island communities know how to survive when most Lowland urbanites only know how to go to a supermarket. Island communities are at the forefront of action against climate change because they know how to work their land sustainably while they will be the first to see the consequences of the climate crisis, as big cities invest in infrastructure to protect themselves from rising sea levels. All the while, the members of these communities are the guardians of our cultural and agricultural heritage, who provide us with food and energy. It’s not just their speech that needs to be protected. Their speech is just one facet of their entire way of life that needs to be protected. You may not see that when you look in the St Kilda folder and see that the typical Hebridean pronunciation of bàta ‘boat’ (sounds a bit like paaaaahhhhtuh) was not a feature of St Kilda dialect, even though St Kilda is a considered a Hebridean island (they said something more like baaaatuh). But all these issues are interlinked and the voices calling for respect and understanding of our world ring out through the records of their speech. This is worth thinking about while COP26 is going on in Scotland’s biggest city, i.e. how linguistic minorities protect the planet and what those (mainly male) world leaders need to do to protect them. Linguistic diversity is a part of our planet’s biodiversity, and so the loss of a dialect is like the extinction of a species and the SSSA like the Natural History Museum in those terms.

Dr Teàrlach Wilson is a former University of Edinburgh student, who completed his PhD in Celtic and Scottish Studies in 2021, looking at the links between Gaelic grammar, dialects, and geography. He now lectures Scottish Gaelic at Queen’s University Belfast and is the founding director of An Taigh Cèilidh, a nonprofit Gaelic community hub in Stornoway, Outer Hebrides.

Meet your LexisNexis Student Associate for 2021/22!

We’d like to introduce you to Noah Norbash, one of your fellow students who is a specialist in working with LexisNexis and all their resources – such as the invaluable LexisLibrary and Lexis PSL databases! We recently met with Noah to discuss what he has planned for the year, and he’s answered the following questions so you can get to know him too.

Tell us a little bit about yourself! Who are you and what do you study at Edinburgh?

Noah outside the magnificent buildings of Old College

I’m Noah – currently a student in the Graduate LLB programme. I grew up in the United States just outside of Boston, but I have spent many a year studying and living in St Andrews, the Veneto region of Italy, London, and finally here in Edinburgh!

Why did you apply to be the student representative for LexisNexis?

I applied to be the LexisNexis Student Associate on campus to not only enhance my own understanding of legal databases, but also to convey my knowledge to my fellow students. As an added extroverted bonus, I also get to have a bit of a chat here and there with interesting people! LexisLibrary has been of extraordinary help to me in my degree programme so far, and no doubt LexisPSL will be of equal significance when I begin the diploma and a traineeship. As a simultaneous LawPALS leader and a LexisNexis Student Associate, I looked forward to giving members of the university community the tools to succeed and achieve whatever they put their minds to.

What do you think is the best feature that Lexis offers for students in the Law School?

The #1 top-notch feature that can be accessed on LexisLibrary is without a doubt the Stair Memorial Encyclopaedia – it is a resource exclusive to LexisNexis, and it contains a wealth of information on every imaginable topic in Scots law with links to any relevant case law and legislation. In a nutshell, it serves as a textbook on the entirety of the laws of Scotland, and its usefulness cannot be overstated! When it came to preparing for moots or even getting a birds-eye view of material in advance of tutorials, the Encyclopaedia can quickly steer you in the right direction for where you need to go.

If you could name one top tip that everyone should know about your platform, what would it be?

A top tip everyone should know about the platform is that you can easily narrow searches of case law to only a particular firm: this is especially useful to those seeking a traineeship to be able to discuss specifically what issues their firm of choice may be facing in today’s legal climate. There is no better way to stand out from the crowd in an interview setting – being able to express niche insider-quality knowledge about the firm that is totally available to applicants is a spectacular way to impress. By reading a firms’ submissions and the judge’s opinion on LexisLibrary, you as an applicant can see the fruits of the firm’s labour and gain a clearer understanding of what the firm seeks to achieve in the courtroom.

When students book a training session with you, what can they expect to get from the meeting?

When students book a training with me, they can expect to gain insight into how to use LexisNexis software in an approachable and friendly setting. Over the course of the year, I will be running training sessions for Foundation- and Advanced-level LexisLibrary Certifications, LexisPSL certification, and Commercial Awareness more generally. Otherwise, students can get in contact with me for any Lexis-themed questions and I will be happy to help! Although I’m not an expert on par with the full-time Lexis Customer Success Managers, I will do all I can to imbue you with the knowledge I have been given and to give you a solid base of LexisNexis database-searching skills that will prove indispensable for the legal journey of your lifetime. Don’t be a stranger!

You can find Noah in his new and fabulous Teams group: tinyurl.com/LexisCorner

Alternatively youcan reach him by email at n.norbash@sms.ed.ac.uk.

Finding Resources: Navigating the Online Library

The Online Library is a vast resource. Whatever you study, you will find what you need in the Library collections. For all that it is wide and wonderful, however, I know (from personal experience) navigating the Online Library can be overwhelming. Read on for tips on where to look for resources and how to get the best out of the Online Library…

Subject Guides

Subject Guides are a great place to start your search for resources. If you haven’t already, head over to the Subject Guides list and find all the most relevant library resources for your subject and more…

Check out our blog dedicated to Subject Guides for more information, coming soon...

Read More

Making library data work for us

Image by 200 Degrees from Pixabay

On 2-4 November I attended the LibPMC Conference (International Conference on Performance Measurement in Libraries). The conference content was really varied, including a focus on the needs of stakeholders and communities and actively using qualitative and quantitative data to improve services and the user experience. Here are some highlights.

- But can it last? How the pandemic transformed our relationship with data. Dr Frankie Wilson, Bodleian Library

- Knowledge is PowerBI: How data visualisation helped inform services during the pandemic. Elaine Sykes, Liverpool John Moore’s University

- Using return on investment to tell the story of library value and library values. Prof Scott HW Young, Prof Hannah McKelvey – Montana State University

- Assembling a Virtual Student Library Advisory Board during COVID-19. Prof Chantelle Swaren, Prof Theresa Liedtka – University of Tennessee at Chattanooga

- Charting the Change: Analysing How Online Delivery Made A Difference to Who Is Accessing Academic Skills Programmes. Louise Makin, Academic Engagement Manager, Liverpool John Moores University.

Database Trials

After a break in arranging database trials these have now restarted. Two current trials that may be of interest to staff and students alike are:

Policy Commons database:

The Library has taken out a one-year trial subscription to the Policy Commons database, a unique database providing access to nearly 3 million curated, high quality policy reports, briefs, analyses, working papers, books, case studies, media and datasets from thousands of policy organizations and think-tanks world-wide. This talk will cover content and search of the database, including searching for tables and graphs, as well as the facility to upload documents. Access to Policy Commons can be found at policycommons.net.

Off-campus access requires the use of the University’s VPN, or to register for a Policy Commons account using a University of Edinburgh email address.

A demonstration of the database will be held for University of Edinburgh users on Thursday 9th December, 10:00 – 11:00. Book a place at this online event at : events.ed.ac.uk/index.cfm?event=book&scheduleID=51607

Europresse:

The library has access to Europresse for a ten-day trial, until Friday 12th November.

This databases provides access to over 6,200 international publications including journals, newspapers, blogs and magazines. Coverage is international with many of the publications included available in their original language and layout, which differs from many of the news databases we currently subscribe to. The range of available sources includes numerous European national newspapers such as Le Monde, Libération and Le Figaro, along with regional newspapers. English language titles such as The Guardian and The New York Times are also available. Full details are on the databases trials page.

If you try out either of these databases (or any of the databases linked on the trials webpage) we’d be really grateful if you would complete the feedback form to tell us what you think. This helps us get a feel for what has been useful to you and whether we should subscribe. Alternatively you can send us feedback or any ideas for future resources we should trial by email on law.librarian@ed.ac.uk.

Europresse trial – French newspapers and magazines, and more…

The Library has arranged a trial of Europresse for a very limited period, for 10 days until 12 Nov 2021. The trial can be accessed from the Library’s E-resources Trials website, or access the following link directly which requires UoE login:

The Library has arranged a trial of Europresse for a very limited period, for 10 days until 12 Nov 2021. The trial can be accessed from the Library’s E-resources Trials website, or access the following link directly which requires UoE login:

https://nouveau-europresse-com.ezproxy.is.ed.ac.uk/Search/Reading

Europresse provides access to over 6,200 publications including journals, newspapers, blogs, and magazines. Coverage is international with many of the publications included available in their original language and layout. The database includes numerous European national newspapers such as Le Monde, Libération and Le Figaro, along with regional newspapers. English language titles such as The Guardian and The New York Times are also available. Thematically, Europresse titles cover the Humanities and Social Sciences, Politics, Law, Economics, Finance, Science, Environment, IT, Transports, Industry, Energy, Agriculture, Arts and culture (Lire, Le Magazine littéraire, World Literature Today, Télérama, Rock and Folk…), Health, and event Sports (L’Équipe, France Football, Sport 24…). It also includes some TV and radio transcripts, biographies and reports, images, audio and video content.

As an example, it provides the image version of today’s Le Monde newspaper which is a welcome alternative to the text version of Le Monde via Factiva. Le Monde Historical Archive, which we subscribe to, covers only 1944-1999.

You can see the full list of publications provided by Europresse here:

https://nouveau-europresse-com.ezproxy.is.ed.ac.uk/Pdf

Please send feedback via the E-resources trial feedback form.

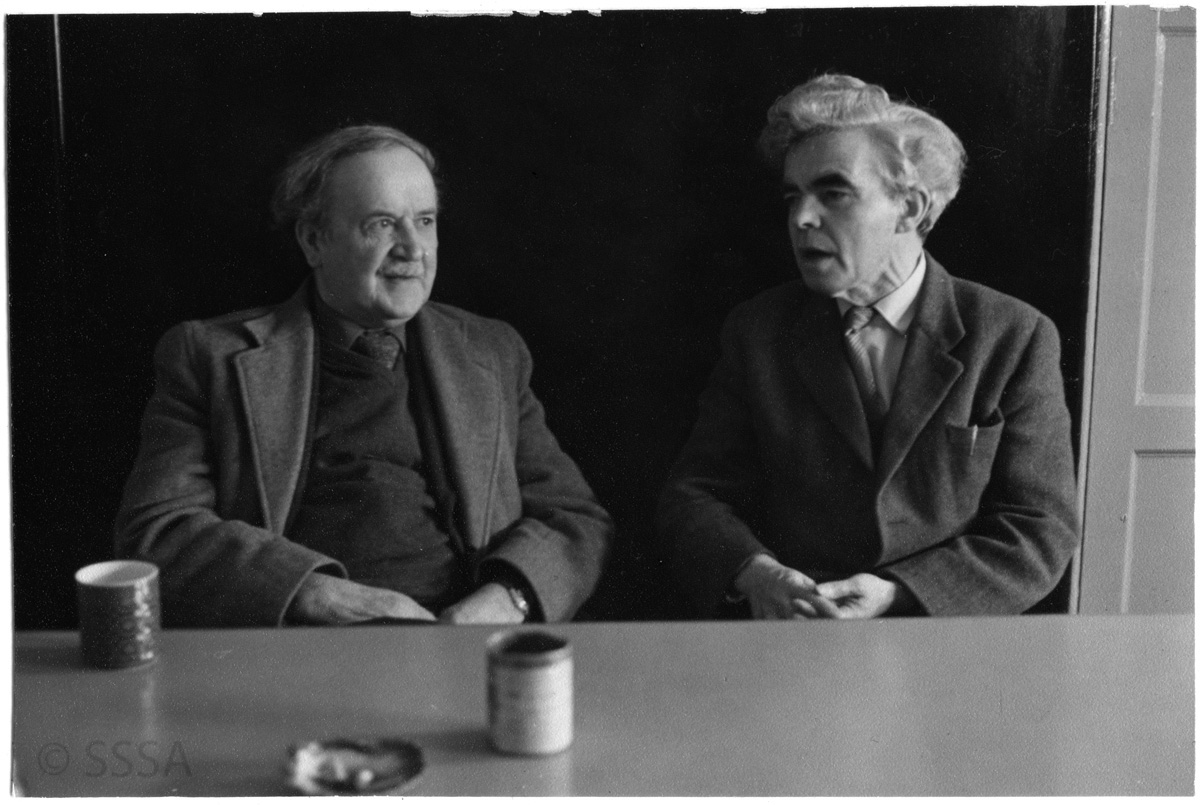

SSSA in 70 Objects: Photograph of Sorley Maclean and Ian Paterson

Sorley MacLean and Ian Paterson in the School of Scottish Studies tea room, Summer 1981. © The School of Scottish Studies Archives, Ref: V_2b_8119

This week saw the 110th anniversary of the birth of Raasay poet Sorley MacLean (26 October 1911 – 24 November 1996) and so today’s blog is a great opportunity to share with you a photograph from the collection that I really like, for two reasons.

Here are Sorley and Ian Paterson, sitting at the tea table in the School of Scottish Studies. Ian Paterson was a native of Berneray and worked at The School of Scottish Studies first as a transcriber and then began collecting fieldwork of his own. In July 1974 and November 1978, Ian recorded Sorley reciting his poems at The School. You can hear these recordings via Tobar an Dualchais by following the Reference links below:

It is an incredible gift to be able to listen to one of our greatest contemporary Gaelic poets reciting his own work in fine, resounding voice.

I like the candidness of this image too; such a lack of ceremony. Two people, taking their ease, caught in a conversation while having a cup of tea. And that is the other thing I like about this image. It was taken in the Tea room at 27-29 George Square, in the School of Scottish Studies building and for anyone who worked, studied or had connections in the building, the tea room and the tea table was a special place indeed.

From special occasions to plain old elevenses, there was always a community feel about that room and you were never quite sure who else would be joining you for your tea. When the Celtic and Scottish Studies department and the Archives moved in 2015 the tea table was much mourned as that hub. We often hear stories from people who have memories of being at the tea table and so we thought it would be great to share some of these here on the blog, along with some more photographs from our collections. If you have any memories of occasions in the tea-room, no matter how long or short the tale, please drop us a line at scottish.studies.archives@ed.ac.uk, or leave us a comment below.

Louise Scollay, Archive & Library Assistant

Collections

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Projects

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....