Home University of Edinburgh Library Essentials

December 20, 2025

Behind the Lens: LGBT+ History Month

February is LGBT+ History Month and this year’s theme is #BehindThe Lens. This aims to celebrate “LGBT+ peoples’ contribution to cinema and film from behind the lens. Directors, cinematographers, screen writers, producers, animators, costume designers, special effects, make up artists, lighting directors, musicians, choreographers and beyond.” (LGBT+ History Month, 2023)

To help you learn more we’ve pulled together just a small selection of Library resources that will allow you to start to look ‘Behind the Lens’.

Books and more books (we are a Library after all)

Films, TV, documentaries, etc.

Doing your own research

Books and more books (we are a Library after all)

Why not start with The Oxford handbook of queer cinema as an introduction. This hefty tome covers a wide variety of topics including silent and classical Hollywood films, European and American independent and art films, post-Stonewall and New Queer Cinema, global queer cinema and new queer voices and forms.

Why not start with The Oxford handbook of queer cinema as an introduction. This hefty tome covers a wide variety of topics including silent and classical Hollywood films, European and American independent and art films, post-Stonewall and New Queer Cinema, global queer cinema and new queer voices and forms.

New queer cinema: A critical reader considers the filmmakers, the geography, and the audience of New Queer Cinema. While Queer cinema in Europe brings together case studies of key films and filmakers in this area. Sapphism on screen: Lesbian desire in French and Francophone cinema focuses even more specifically on films made by male and female directors working in France and other French-speaking parts of the world. In a queer time and place: Transgender bodies, subcultural lives is the first full-length study of transgender representations in film but also art, fiction, video and music. Whereas LGBTQ film festivals: Curating queerness pays homage to the labour of queer organisers, critics and scholars. Read More

‘Nothing is Here for Tears’: Helen Cruickshank Bids Farewell to F. Marian McNeill

This year marks the fiftieth anniversary of the death of folklorist F. Marian McNeill on 22 February 1973. Edinburgh University Library holds the manuscript of a memorial poem written by her close friend Helen Cruickshank on the day of McNeill’s death. Today we publish a blog by Ash Mowat, a volunteer in the Civic Engagement Team, introducing our Helen Cruickshank Papers (Coll-81) and celebrating the friendship between Cruickshank and McNeill (with additional material from Modern Literary Collections Curator Paul Barnaby). Read More

On trial: British Online Archives collections

*The Library now has permanent access to Britannia and Eve, 1926-1957 and The Tatler, 1901-1965. You can access these either from Newspapers, Magazines and Other News Sources or the Databases A-Z.*

Did you know the Library currently has trial access to a number of databases from British Online Archives?

British Online Archives are one of the U.K.’s leading academic publishers. Their goal is to provide students and researchers with access to unique collections of primary source documents. Their databases cover 1,000 years of world history, from politics and warfare to slavery and medicine.

At the Library we currently have trial access to 7 databases from BOA. All can be accessed from the E-resources Trials page:

Britannia and Eve, 1926-1957

Trial ends: 3rd March 2023

William Drummond’s ‘Flowres of Sion’: A Unique Copy of a Major Work

This year marks the quatercentenary of the publication of Flowres of Sion (1623), an important volume by William Drummond of Hawthornden (1585-1649), one of Scotland’s major 17th-century poets and one of Edinburgh University Library’s greatest benefactors.

William Drummond of Hawthornden

An alumnus of Edinburgh University, Drummond started collecting books shortly after he graduated in 1605. He assembled a superb private library, which ranged widely across the fields of literature, history, geography, philosophy, theology, science, medicine and law. From the mid-1620s, he began gifting works from his library to his alma mater, eventually donating over 600 volumes. Drummond thus provided Edinburgh University Library with some of its greatest treasures, including two Shakespeare quartos and works by Ben Jonson, Edmund Spenser, Michael Drayton (a close friend of Drummond), and Sir Philip Sidney.

Drummond’s also donated copies of his own works, including a unique copy of the first edition of Flowres of Sion (De.4.53), along with the revised and expanded second edition of 1630 (De.4.113).

Digital Research Services: How we can support your research

[This is a guest blog post by our new DRS Facilitator Sarah Janac. The Research Data Service is one of a number of digital research services at the University of Edinburgh.]

Many researchers rely on digital tools and computational methods for their work, and, for this, the University offers several state-of-the-art facilities. However, it is easy to get lost in the sheer number of tools and providers. Digital Research Services are here to help.

Who are Digital Research Services (DRS)?

Digital Research Services offer a single point of access for all things digital research across the University. We connect researchers with the digital tools and services from Information Services and other providers. We make it our priority to deliver tailored support so that researchers get the best use of the resources out there.

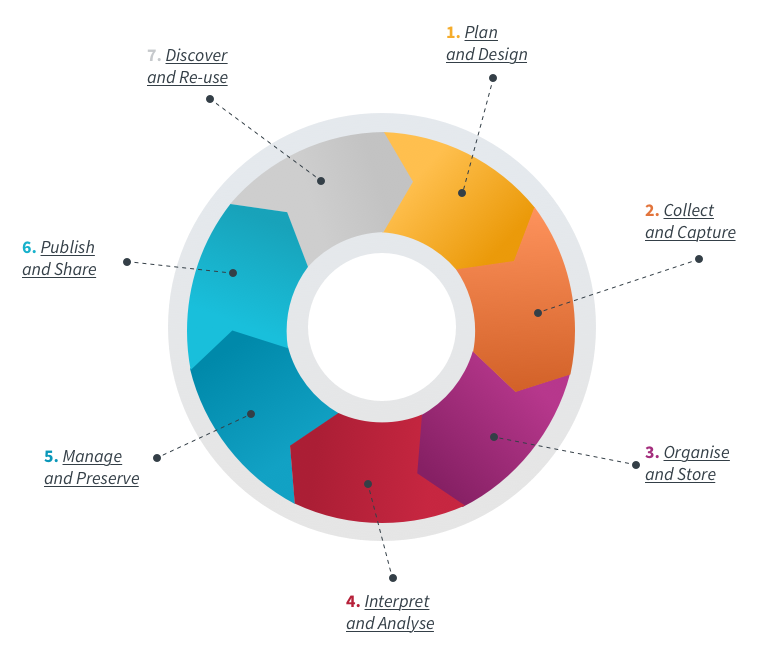

We love the research lifecycle!

The research lifecycle is the cornerstone of our work. We collaborate with service providers from Information Services Group and beyond to support you in all stages of your research and anticipate challenges which might come up. For instance, we can support you in developing your funding application, ensuring you fully cover the costs related to the digital aspects of your project. We can help you devise a plan for storing your data properly and share it with your collaborators. We can support you in finding the research computing services required for analysis. We will help you think about archiving your data and making it accessible to other researchers, utilising trusted repositories. Finally, we can also support you in the dissemination of research outputs.

How do we support you?

First of all, our website offers a one-stop shop for digital tools, training and events. You can browse through the different tools that the University offers, see if there is relevant training and read up on case studies describing how these tools have been used by researchers before.

If you have specific questions or require tailored support and advice, you can get in touch with one of our team members. We are a small team of 3 people, each with expertise for one of the three colleges:

- Eleni has a background in digital humanities. She has been a research facilitator for a number of years now and is the first port of call for researchers at the College of Art, Humanities and Social Sciences;

- Andre has a background in civil engineering, both in industry as well as in academia. He is there to support researchers in the College of Science and Engineering;

- Sarah has academic and hands-on experience in the medical field. She is here to assist with queries from the College of Medicine and Veterinary Medicine.

We work closely with technical experts of various service providers and have contacts across the University. This means that if we can’t answer your question ourselves, we will find someone who can.

Finally, we have a range of exciting events coming up! These can help you further your digital skills, grow your network and exchange ideas.

Upcoming events in Semester 2

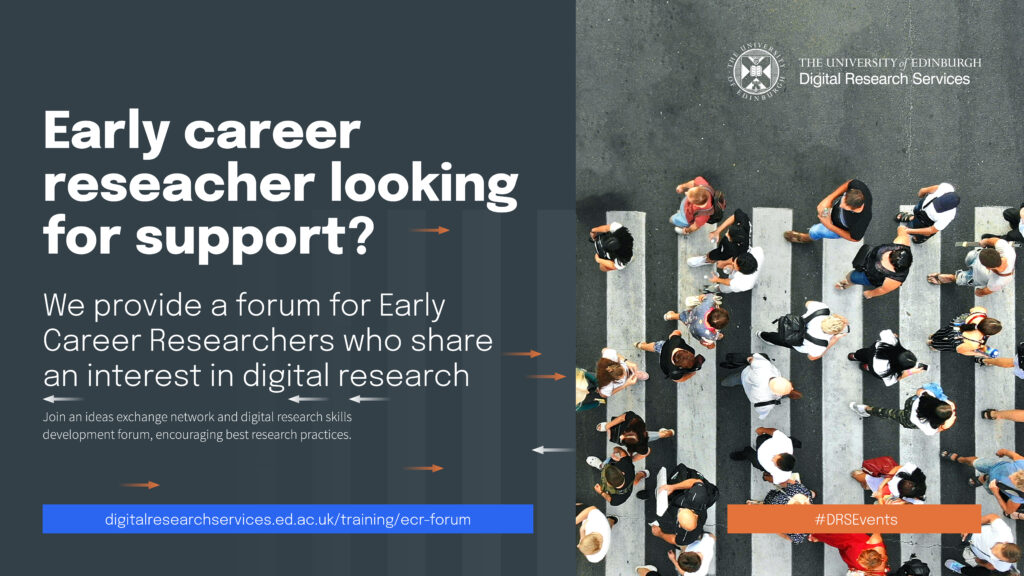

Early Career Researcher Forum

The Early Career Researcher Forums provide a platform to exchange ideas, develop a network and explore opportunities on topics relevant to digital research. Members of the forum can propose a theme and lead discussions based on their research interests. These may include: the creation of digital management plans; use of various digital tools and resources; data storage/preservation/sharing; publication of research outputs; open publishing; etc.

The forum is open to Early Career Researchers and PhD students at the University across all schools – the aim is to encourage interdisciplinary dialogue and networking. The Research Facilitation Team will be present to help lead the sessions. Sign up here.

Digital Research Ambassador Internship Scheme

After a successful run in the previous years, Digital Research Services are planning another fully funded internship scheme. We will be matching interns – postgraduate students with strong digital research, data and computing skills – with host projects across the University.

- As an intern, you will bring in data and research compute expertise, contributing to digital skill development and project planning. In addition, you will gain hands-on interdisciplinary research experience.

- As a host, you will get support and gain new perspectives in using digital tools and services. You will develop additional dimensions to your digital research plans and inspire a new generation of researchers.

If you would like to take part, please register your interest here so we can plan accordingly. More information, including previous projects, can be viewed here.

Lunchtime Seminars

The seminars are open to all, and will cover a wide range of themes and research services. They will help you gain awareness of digital research services, learn the fundamental aspects of the digital research life cycle and discover the challenges and opportunities of data and computing services.

There is a mini networking session immediately before each lunchtime seminar.

The themes for Semester 2 are as follows:

- Organise and Store |30th March 2023. Book your place here

- Publish, Share and Preserve | 28th April 2023. Book your place here

- Interpret and Analyse | 17th May 2023. Book your place here

Keep in touch!

You can also stay up to date by joining our mailing list and following our Twitter and LinkedIn pages.

Link to our website: Digital Research Services at the University of Edinburgh

Link to our brochure: DRS Facilitation – UoE Digital Research Services Brochure DIGITAL.pdf – All Documents (sharepoint.com)

Sarah Janac

Digital Research Services Facilitator

Information Services

Sounds of St Cecilia’s

Recently I have had the joy of photographing a range of instruments from the collections at St Cecilia’s Hall .

Over the last few years, staff at St Cecilia’s have been identifying instruments currently displayed that need new photographs taken. In the end, approximately forty instruments were identified as needing re-photographed as the existing images were either black and white, of poor quality (typically scans of slides) or were taken before conservation treatment was carried out on the instruments and it was deemed necessary to update these images to better reflect the current state of these parts of the collection.

The aim of this project is to incorporate more sound into the visitor experience at St Cecilia’s Hall, through stand-alone interactives in each of the galleries as well as individual hand-held devices. A more dynamic website will replace the current app and can be used both in the stand-alone kiosk and on a smartphone/tablet. These new images will be incorporated into the dynamic website/app and represent the collections both online and in-gallery, as well as replace the existing images on Musical Instrument Museums Online (MIMO) – a site dedicated to acting as a single access point for information on public musical instrument collections from around the world.

Spending a wee while with Lyell

Following in the brilliant footsteps of Claire, Sarah and Joanne – we have been lucky to have Sarah Partington working on conserving the Lyell Collection. For 14 weeks, Sarah was able to finally tackle one series of records that had been assessed, but not worked on, and, to provide a wee bit more general TLC to the collection. An extra layer of care, as it were. Here, she tells us what that has involved:

As the Charles Lyell Project continues, more is being understood about the collection. The entire collection is comprised of different accessions, made at different times. Careful interrogation of the different series is allowing us to understand how they fit together, and, how Lyell used them.

Lyell’s collection of Offprints is similar in scale to the two series of correspondence, demonstrating how collecting and reading different papers would help him stay abreast of the latest finds, research and thinking.

An Offprint is a separate printing of a work that originally appeared as part of a larger publication, usually one of composite authorship, such as an academic journal, magazine or edited boos. Offprints are used by authors to promote their work,and ensure a wider dissemination and longer life that might be achieved by the publication alone. They are valued as being akin to the first separate edition of the work, and as they often are given away, may bear an inscription from the author. Historically, the exchange of Offprints has been a method of correspondence between scholars.

I began my Lyell journey by cleaning and rehousing the 18 boxes of Offprints collected by Lyell. Currently uncatalogued, voluminous, and densely packed in non-archival boxes, these records had been assessed, and found to be exhibiting signs of historic mould. This needed to be dealt with, as although historic and not active, it could ultimately pose a cross-contamination risk to other collections. These records could not be accessed in their current state – both by archivists, and by any potential users.

Surface dirt had to be carefully removed, following Health & Safety guidance.

Cleaning the offprints proved somewhat of a challenge (even for a mould aficionado like myself!).

In some cases, the biological damage was so severe that the paper had partially deteriorated. This complicated the cleaning process, because I had to mitigate further structural damage, whilst still ensuring the satisfactory removal of damaging mould. Throughout the cleaning process, I had to carefully to observe Health and Safety guidance and take precautions to protect my colleagues and myself.

I cleaned each page in the fume cupboard, eliminating mould using a museum vacuum on a low-suction setting, with an interleaving layer of mesh to prevent the loss of material.

An affected Offprint before cleaning. Working in the fume cupboard, all of the surface mould was removed.

After everything had been cleaned, I rehoused the offprints in acid-free boxes, separating out those that had been especially cramped in their original housing. Rehousing generally equates to more boxes! To support the greater extent of boxes, we rationalised shelving in the storeroom and created additional space.

Cleaning this series of the collection was time consuming – but the benefit of the newly cleaned items to the health and safety of the collection is immense. Now properly re packaged, and stored in a climate-controlled environment, work can begin to start to make them discoverable.

A conservator’s worst nightmare: the pocket folder! The contents can be damaged simply taking them out!

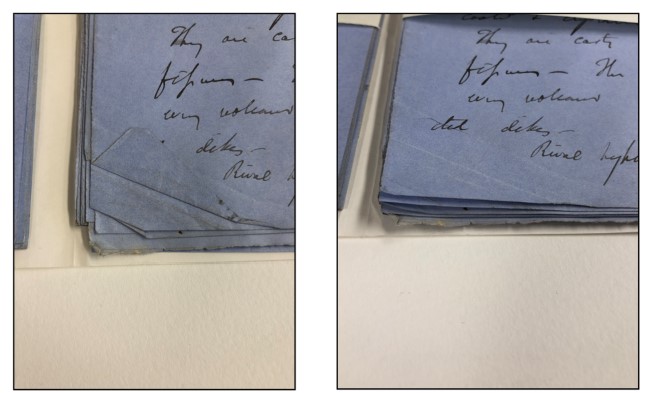

At the end of the Offprints series, 5 boxes were identified as being different; they were not Offprints but were actually manuscript material. This material was not housed in a suitable manner, with the usual, historical pocket folders having been chosen as the filing weapon of choice! Not only were these not up to archival standard, but they were also overfilled, and mostly contained items of a non-uninform size and type.

Our closer inspection confirmed that these boxes contain examples of Lyell’s editorial notes, his review of chapters, and included letters, drawings, engravings, notes, maps, as well as his original packaging, which was large sheets of contemporary newspaper.

The different format and sizes meant that there was a risk that items could fall out of sequence or get caught on the edges of the folder when removing or replacing material. To depose the evil pocket folders, I opted for acid-free triptych folders, which open out in such a way that the material is instantly accessible, therefore reducing the risk of damage occurring. I separated out the material into more than one folder where required, making sure that none of the folders were too overcrowded. Thinking about access, and as the items are still loose, we will create guidance for our Reading Room Team and users, to ensure folders are carefully handed over when being accessed.

As well as rehousing these manuscript papers, I was able to look out for documents that needed a bit more TLC. After a little bit of training from Paper Conservator, Emily Hick, I was ready to start carrying out some basic interventive treatment, such as flattening folds and removing pins. I flattened folds manually with a bone folder and an interleaving sheet of bondina and, where appropriate, I used a ‘mister’ – a small hand held tool, used within the beauty industry which sprays a fine mist – to apply localised humidity to the paper, which could then be placed under magnets and left to flatten.

Manually flattening folds.

Sarah using a beauty mister to lightly flatten folds.

Folds shown before and after treatment. Much more relaxed!

Some original pins were still in place, which had started to corrode and were difficult to remove. Emily gave me a pair of pliers and gentle techniques to carefully wiggle them out without causing further damage to the paper. I replaced them with an acid-free paper slip to group pages together. In order to retain the integrity of the sequence, I ensured that nothing came out of order and the items were clearly stored with their original packaging. Any outsized items, or items that required further treatment, were flagged up in an Excel document.

Geared up for another rehousing spree, I then moved onto to the most recent accession in the collection, the Acceptance in Lieu material, consisting of 18 boxes. The strategy this time was to start at the end of this series, giving back a bit more time and care to this series of records.

Loose-leaf material, now held in an acid-free paper fold

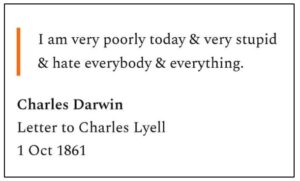

Being given the opportunity to support access and research into the Lyell Collection through conservation work has been a real privilege. As an aspiring paper conservator, it has been great to add a few more paper treatment strings to my bow, and to apply my skills to a collection this significant. By working closely with the Lyell Collection, I have also learnt a lot about him and the way in which he planned, researched and worked. I’ll leave all of you lovely Lyell fans with what is possibly my favourite thing that I have learnt whilst focusing on Lyell and his correspondence… apparently Charles Darwin enjoyed a good moan to his pals now and then like the rest of us!

A big thank you to all the conservation people who have contributed their time and skills, and to our funders for ensuring Lyell’s records are in the best condition they can be. There is always more work to be done – but for now, we can look to start the work to make these records available to people.

The History of Access to University

Ash Mowat is one of our volunteers in the Civic Engagement Team. Ash has been researching the history of access to study at University, via our University Archives and shares that information with us here.

Introducing Ash: I was born and have lived in Edinburgh most of my life. I attended University of Glasgow in the late 1980s where I hoped to complete an honours degree in English literature, but unfortunately due to ill health I was only able to obtain a degree at ordinary level. I have diverse interests in literature, the visual arts and science and history. I also worked for almost 25 years in social housing and have a passion for social justice, and equalities.

This piece outlines the history of access, affordable or otherwise, to University Education. It primarily focuses on the 20th century unto the present, and some features will apply to UK Universities and not just University of Edinburgh or other Scottish Universities, as many of the laws and practices were implemented by UK Government. Some aspects, however, are particular to Scotland following devolution in 1999.

Robert Anderson (Professor emeritus of History University of Edinburgh) summarises the changing systems of fees and grants available for university students to pay or access.[1] He highlights the period between 1962 and the 1990’s when ‘University education in the UK was effectively free as the state paid students’ tuition fees and also offered maintenance grants to many’. There is also a brief summary of grants available in early periods.

The following tables aims to summarise some of the history of changes in direct and indirect accessibility to a University education.

| Dates | History |

| 19th Century | There was no free access to study at University in Scotland, however unlike in England there were some State grants, but not wider UK Government supplementary benefits like rent assistance, as these would not come into effect until the implementation of the Welfare state in the 1940s. Fees and living costs were also low in Scotland, in comparison to English Universities, especially the prodigious ones like Oxford and Cambridge.

In the pre second world war period, those on lowest incomes in the UK could be given a Board of Education Endowment to fund their University studies. This came with the proviso that on graduation they undertook one year in teacher training and subsequently worked for several years as a school teacher. If they failed to honour this, their grant would have to be repaid. Interestingly in this period, students from middle and upper classes disproportionally studied subjects in the likes of medicine and engineering, whilst those from lower income backgrounds tended to study in the arts, perhaps a reflection of the higher fees and costs associated with subjects like medicine. Male students even from lower income backgrounds tended to see their financial, career progression and class status greatly improved following graduations, an outcome not reflected equally amongst female graduates, many of whom if went on into employment would see their careers often constricted such as to be within the School teaching sector.[2] |

| 1962 to

1997 |

There were no fees payable to study at UK Universities in this period as there were met by the state. Maintenance grants were available to those without their own funding means or from parental income. By 1963 almost 70% of UK University students were receiving grants from UK Government state funding.

Wider benefits were available from UK Government, including Housing Benefit to meet in part or full rental costs. Students could keep this Housing Benefit and therefore retain accommodation over University holidays, and if eligible claim unemployment benefits in the breaks between terms. However, by the mid-1990s UK Government Benefits such as Housing Benefit and Income Support were abolished for most full time students (one exception being lone parents), with the Government argument being that students should receive financial assistance solely from the further Education system only and not also from the wider Welfare system. |

| 1979 to 1988 | Access University systems in Scotland. Access schemes, where students without standardly required qualifications could gain entry to study at University level, were introduced in Glasgow University (1979), Dundee University (1980), Aberdeen University (1984), Strathclyde University (1985), and Edinburgh University in 1998.

These were often ran in partnership with local colleges and were limited in number of students permitted annually. The subsequent introduction withdrawal of grants and access to Welfare Benefits as detailed below, served to undermine the viability of the access and general admission routes into a University education from those without their own or parental means of funding or support.[3]  31st May 1988 newspaper article on access course launch (EUA IN1/ADS/SEC/CRR) |

| April 1988 | From April 1988, a series of incremental cuts were introduced by the UK Government reducing rates of Housing Benefit and supplementary benefit (financial benefits payable to students during summer term break). This was exacerbated by introduction of the Community Charge, more commonly referred to as the “Poll Tax”, a despised and unjust tax as was charged as a flat rate on all individuals regardless of wealth. The hugely unpopular Poll Tax (in a poll 78% of UK population opposed it) led to protests across the UK culminating in a huge rally of over 200,000 people in Trafalgar Square London in 1990 where serious rioting ensued. The Poll Tax was subsequently abolished and replaced by Council Tax in 1993, a still problematic tax but one based on property value and with ability to pay aspects and rebates available. No Council Tax is payable in properties exclusively occupied by full time students.[4] |

| 1989

to 1990 |

In November 1989, in what was reported as the biggest ever to date UK University demonstration, a march and rally took place to protest the viewed as unfair Student Loan scheme being introduced from 1990. Over 20,000 were estimated to have attended. The introduction of Student loans was driven by the UK Government seeking to withdraw Welfare state benefits from those in further education.[5]

On their introduction in 1990, some 180,000 UK students took out a loan in the first year, for a then average of £390.00.[6] |

| 1991 | The 1991 Student Hardship Report of the Scottish Presidents Group demonstrates the impact on loss of benefits on students. Rents had increased by 11% in one year from 1990 to 1991. In the same time students who previously received housing benefit during the summer vacation to cover rent and now having this entitlement cancelled, were losing £457.00 over a 15-week period. (Edinburgh figures, equivalent to £1229.00 today). Income Support was also withdrawn with the UK Government reasoning that students would be able to find work during holidays and thereby afford rent and living costs without welfare assistance. However when this was introduced 36% of Edinburgh University students said they could not find work (this was during the height of a major recession), and a further 34% couldn’t be available for work due to their course study commitments.

Nevertheless the numbers of students who were also required to work during term time continued to rise, despite the pressures to combine this with adequate time to manage their studies. Despite the UK Government assertion that students should fair equally or better under the student loans system, 54% of Edinburgh University students polled stated they were worse off than under the previous system of grants and welfare benefits. The report concludes, “Students are encouraged to acquire significant debts, with little prospect of lucrative employment at the end of their studies to repay these debts. The policy seems, at best, unlikely to encourage increased numbers of students to enter higher education.”[7]  The 1991 student hardship report of the Scottish Presidents Group, EUA IN1/ADS/SEC/CRR |

| 1998 | The reintroduction of tuition fees to enrol at UK Universities was implemented by UK Government, with fees set initially at £1000.00 per annum. |

| 2001 | From April in Scotland, the Graduate Endowment Scheme was introduced. This brought in University study in Scotland without any tuition fees, however on graduation a fee of £2000.00 was repayable by the student. [8] |

| 2004 | Tuition fees increased to £3000.00 per annum. [9] |

| 2006 | From this year, student loans could be issued to meet not just living costs but to cover tuition fees. [10] |

| 2007 | The Scottish Government introduce free tuition fees to Scottish students, or students from other nationalities whose home has been in Scotland for at least three consecutive full years. Student loans remain in place to assist with living costs. [11] |

| 2010 | Tuition fees to students at English Universities increased to £9000.00 per annum (currently £9250.00 per annum). [12] |

In addition to the affordability of studying at University, one question raised is the outcome for the graduate in terms of student loan debt burden and prospective career benefits in having a degree. Before going into the dry financial bones of the issue, it is worth reflecting that people choose to go to University primarily for the joy and enrichment of learning in the subjects of their choice, and for the wider social and personal development experiences that come with it.

Price Waterhouse Coopers in their 2007 report The Economic Benefits of a Degree, included one somewhat start and contrasting result based on choice of subject studied. Those studying Medicine or Dentistry could expect to see an additional lifetime earnings premium of £340,000 throughout their working career as a consequence of their specific degree obtained. Conversely, the lifetime earnings premium for an arts graduate is just £35,000. [13]

The burden of student loans accrued by students needs to be considered and can be off-putting to many potential University applicants. In England the average student loan debt is currently £45,000, whilst for Scottish students entitled to free tuition fees the average debt is much lower at £15,000.

Student loans accrue interest currently around 6% per annum, but don’t have to begin repayments until salary exceeds £27,295 per year, and even then by phased instalments: e.g. on a salary of £31,295 per year, annual repayments to loans would be £360.00. Student loans cannot be entered into bankruptcy, but any remaining balances will be written off automatically after 30 years (and earlier if individual is disabled and unable to work).

If you’d like to know more information about the archival documents consulted during the writing of this article, you can get in touch on is-crc@ed.ac.uk.

[1] https://www.historyandpolicy.org/policy-papers/papers/university-fees-in-historical-perspective#:~:text=Introduction,at%20%C2%A31000%20per%20year. Accessed on 07/12/22.

[2] https://www.historyandpolicy.org/policy-papers/papers/going-to-university-funding-costs-benefits. Accessed on 07/12/22

[3] Students/Access Courses, 1986-10-01 – 1988-03-01, 31st May 1988 newspaper article on access course launch. Accessed on 30/11/22.

[4] April 1988, 1987/1988 – The Student (ed.ac.uk). Accessed on 07.12.22.

[5] “biggest ever student march slams loans” https://www.era.lib.ed.ac.uk/bitstream/handle/1842/25651/30_11_1989_OCR.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed on 7th December 2022.

[6] take up statistics 1991-2005 (archive.org) accessed 0n 7th December 2022

[7] ‘”The 1991 student hardship report of the Scottish Presidents Group”, Students/Access Courses, 1986-10-01 – 1988-03-01, University of Edinburgh Archives. Accessed on 07/12/22.

[8] untitled (legislation.gov.uk) accessed on 7th December 2022

[9] Timeline of tuition fees in the United Kingdom – Wikipedia accessed on 7th December 2022

[10] The Education (Student Loans for Tuition Fees) (Scotland) Regulations 2006 (legislation.gov.uk) accessed on 7th December 2022

[11] The Education (Fees and Awards) (Scotland) Regulations 2007 (legislation.gov.uk) accessed on 7th December 2022

[12] Timeline of tuition fees in the United Kingdom – Wikipedia accessed on 7th December 2022

[13] https://1drv.ms/b/s!AjnBrv_NtsULlRV4RgGY1sjnK-O1 accessed on 7th December 2022

Resolving to reference in 2023

Whether you’re the type of person who makes New Years resolutions or not, we hope you’ll consider resolving to get comfortable with referencing this year. We have lots of resources available to help you with citations in your assignments, and we know it’s something many students struggle with and so can often leave to the end of their work. Some top tips for getting ahead of the referencing panic:

- Record the information you read as you go. You can do this using a reference manager, bookmarking tools in your browser or DiscoverEd, or good old pen and paper. Whatever method you’re comfortable with, starting off with good organisation will help you down the line.

- Leave more time than you think you’ll need. Do you usually give yourself a day or two before the assignment deadline to sort references? Double it! Triple it! Build in contingency time for writing up and correcting references – and for asking for help if you need it – and if you end up not needing all that time then submit early and then reward yourself with a treat for being ahead of the game!

- Be consistent. There are lots of referencing styles out there (you may already be familiar with Harvard, APA, Chicago, OSCOLA), but whichever one you use for your work, be consistent in how you reference. Make sure you have all the component parts of each type of reference and then style them in the same way each time – this helps you spot when information is missing as well as looking good.

- Use the tools available to you. This includes reference managers like Endnote, Zotero and Mendeley (or any others!), or even ‘quick’ citation engines like ZoteroBib or Cite This For Me. We highly recommend you use Cite Them Right Online which is a database we subscribe to for all staff and students to use – it will show you how to construct references for every type of material in a huge range of styles. Not sure how to reference a personal email, a blog post or a youtube clip? Use Cite Them Right to check! NOTE: Please make sure you check any reference that is created by a citation tool, as they are not guaranteed to be accurate.

- Get help in plenty of time! Still feeling lost at sea? We’ve got training sessions on the MyEd booking system and also recordings on Media Hopper (click on ‘174 media’ below the title card for the full list of videos) designed specifically to help you. There’s also part of the LibSmart online information literacy course dedicated to the basics of referencing, and we have a whole subject guide on the topic. If all else fails, contact your Academic Support Librarian and ask for a one-to-one appointment where we can sit down with you and work through the problems you’re facing.

Do you have any top tips for referencing? We’d love to hear them, you can leave them in the comments or tweet us @EdUniLibraries.

What the NFT?!

The purpose of this blog post is not to endorse or criticise NFTs but to explain what they are and – briefly – discuss if they are relevant to libraries.

When a colleague asked me if I know what non-fungible tokens are, I must confess that she gave me pause. As I regained my bearings, I remembered that mobile goods can be classified as fungible and non-fungible. According to my old Civil Law textbook – fungible goods can be determined by number, measure or weight therefore can be replaced with similar ones when executing a contract. I also remembered the example given by the professor: if someone buys one tonne of apples that go bad before delivery, then the seller must replace them with another tonne of apples of similar type and quality and the contractual obligation can be still respected. The seller will bear the loss but that’s the nature of fungible goods. Per a contrario, this means that non-fungible goods are irreplaceable or unique goods.

A non-fungible token (NFT) is a record of who owns a unique piece of digital content. It’s the digital equivalent of the deeds of a house. Ownership is recorded on blockchain – a publicly accessible and transparent cloud ledger for digital assets. Content can be anything – art, music, graphics, tweets etc. – as long as it is unique.

Last year, American band Kings of Leon released their When You See Yourself album using the usual channels (vinyl, CD, streaming etc) and as an NFT. In fact, there were two types of NFTs: one digital download deluxe version of the album which came with some digital & real perks was sold for $50. The other type is a set of 4 front-row seats for all future Kings of Leon concerts. 18 such NFTs were minted and only 6 were sold – the rest will be auctioned in the future. This may make more economic sense for investors or fans of the band as they can use them or sell / rent them but still it depends on how long the band will stay together.

One key advantage is that NFTs will put all money directly (and immediately) in the pockets of the artists, but the list of possibilities is endless, being limited by technology, creativity and – crucially – whether NFTs will get enough traction to provoke a shift in the industry. Attaching copyright or royalties to the NFT is theoretically possible but it may not be viable for all types of content.

Are NFTs relevant to libraries?

NFTs are not similar with the ebooks that can be bought from Amazon or other publishers. Unlike Kindle books, NFTs are unique (or limited series) and come with the ownership of the digital book and therefore can be easily resold on blockchain.

Many universities and university libraries have physical possession and sometimes ownerships of rare and limited-edition items which can be digitised, tokenised, and auctioned. Many of these items should be digitised for preservation purposes anyway. As money are always tight, NFTs may look like a source of income as well as creating opportunities for partnerships. Libraries have always been at the forefront of research & innovation and were among the first to embrace some of the innovative practices the internet has unleashed. Any university library with an open-minded IT and finance department should be able to mint NFTs.

On the negative side, there’s a significant ethical problem as usually university libraries are in the business of making the information more fungible not making it non-fungible. University of Edinburgh’s vision is that ‘our graduates, and the knowledge we discover with our partners, make the world a better place’. We cannot do that by restricting access to knowledge. Another equally significant problem is trust – is the NFTs (and the other cryptocurrencies) bubble going to pass the test and become mainstream or is it going to burst just like the tulip fever in the 17th century?

Like any digital creation, NFTs do require ongoing maintenance for their existence. University libraries have the experience of providing long-term preservation for items they store and fortunately the life expectancy of a library is longer than that of a rock band.

A simple scan (even a 3D one) of a unique manuscript or artefact may not be enough of an incentive for someone to buy an NFT. To make them desirable, something new, innovative should be added. This may be an ideal opportunity to innovate, to create partnerships with students and young, original creators and help them build their careers.

Collections

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Projects

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....