Following in the brilliant footsteps of Claire, Sarah and Joanne – we have been lucky to have Sarah Partington working on conserving the Lyell Collection. For 14 weeks, Sarah was able to finally tackle one series of records that had been assessed, but not worked on, and, to provide a wee bit more general TLC to the collection. An extra layer of care, as it were. Here, she tells us what that has involved:

As the Charles Lyell Project continues, more is being understood about the collection. The entire collection is comprised of different accessions, made at different times. Careful interrogation of the different series is allowing us to understand how they fit together, and, how Lyell used them.

Lyell’s collection of Offprints is similar in scale to the two series of correspondence, demonstrating how collecting and reading different papers would help him stay abreast of the latest finds, research and thinking.

An Offprint is a separate printing of a work that originally appeared as part of a larger publication, usually one of composite authorship, such as an academic journal, magazine or edited boos. Offprints are used by authors to promote their work,and ensure a wider dissemination and longer life that might be achieved by the publication alone. They are valued as being akin to the first separate edition of the work, and as they often are given away, may bear an inscription from the author. Historically, the exchange of Offprints has been a method of correspondence between scholars.

I began my Lyell journey by cleaning and rehousing the 18 boxes of Offprints collected by Lyell. Currently uncatalogued, voluminous, and densely packed in non-archival boxes, these records had been assessed, and found to be exhibiting signs of historic mould. This needed to be dealt with, as although historic and not active, it could ultimately pose a cross-contamination risk to other collections. These records could not be accessed in their current state – both by archivists, and by any potential users.

Surface dirt had to be carefully removed, following Health & Safety guidance.

Cleaning the offprints proved somewhat of a challenge (even for a mould aficionado like myself!).

In some cases, the biological damage was so severe that the paper had partially deteriorated. This complicated the cleaning process, because I had to mitigate further structural damage, whilst still ensuring the satisfactory removal of damaging mould. Throughout the cleaning process, I had to carefully to observe Health and Safety guidance and take precautions to protect my colleagues and myself.

I cleaned each page in the fume cupboard, eliminating mould using a museum vacuum on a low-suction setting, with an interleaving layer of mesh to prevent the loss of material.

An affected Offprint before cleaning. Working in the fume cupboard, all of the surface mould was removed.

After everything had been cleaned, I rehoused the offprints in acid-free boxes, separating out those that had been especially cramped in their original housing. Rehousing generally equates to more boxes! To support the greater extent of boxes, we rationalised shelving in the storeroom and created additional space.

Cleaning this series of the collection was time consuming – but the benefit of the newly cleaned items to the health and safety of the collection is immense. Now properly re packaged, and stored in a climate-controlled environment, work can begin to start to make them discoverable.

A conservator’s worst nightmare: the pocket folder! The contents can be damaged simply taking them out!

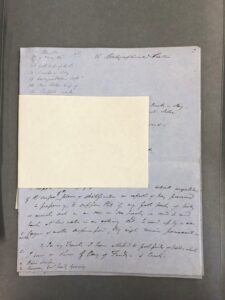

At the end of the Offprints series, 5 boxes were identified as being different; they were not Offprints but were actually manuscript material. This material was not housed in a suitable manner, with the usual, historical pocket folders having been chosen as the filing weapon of choice! Not only were these not up to archival standard, but they were also overfilled, and mostly contained items of a non-uninform size and type.

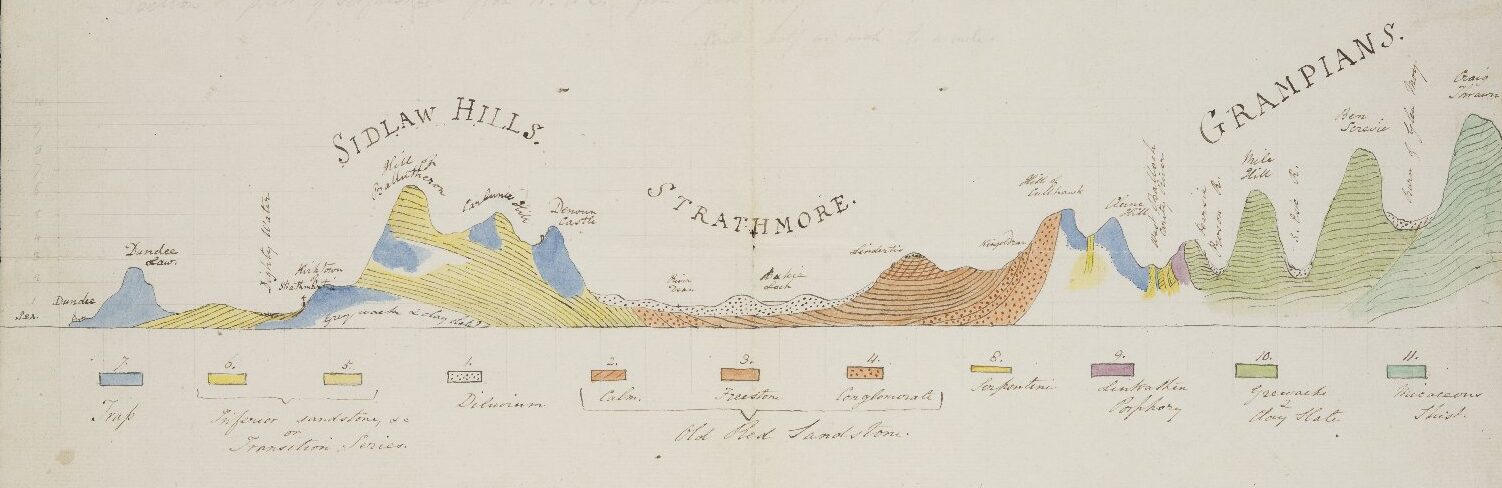

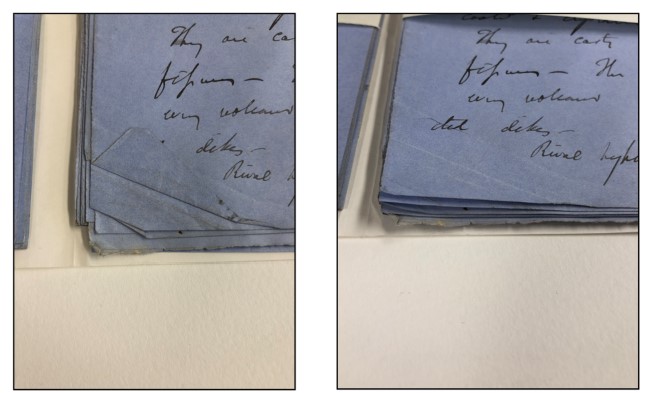

Our closer inspection confirmed that these boxes contain examples of Lyell’s editorial notes, his review of chapters, and included letters, drawings, engravings, notes, maps, as well as his original packaging, which was large sheets of contemporary newspaper.

The different format and sizes meant that there was a risk that items could fall out of sequence or get caught on the edges of the folder when removing or replacing material. To depose the evil pocket folders, I opted for acid-free triptych folders, which open out in such a way that the material is instantly accessible, therefore reducing the risk of damage occurring. I separated out the material into more than one folder where required, making sure that none of the folders were too overcrowded. Thinking about access, and as the items are still loose, we will create guidance for our Reading Room Team and users, to ensure folders are carefully handed over when being accessed.

As well as rehousing these manuscript papers, I was able to look out for documents that needed a bit more TLC. After a little bit of training from Paper Conservator, Emily Hick, I was ready to start carrying out some basic interventive treatment, such as flattening folds and removing pins. I flattened folds manually with a bone folder and an interleaving sheet of bondina and, where appropriate, I used a ‘mister’ – a small hand held tool, used within the beauty industry which sprays a fine mist – to apply localised humidity to the paper, which could then be placed under magnets and left to flatten.

Manually flattening folds.

Sarah using a beauty mister to lightly flatten folds.

Folds shown before and after treatment. Much more relaxed!

Some original pins were still in place, which had started to corrode and were difficult to remove. Emily gave me a pair of pliers and gentle techniques to carefully wiggle them out without causing further damage to the paper. I replaced them with an acid-free paper slip to group pages together. In order to retain the integrity of the sequence, I ensured that nothing came out of order and the items were clearly stored with their original packaging. Any outsized items, or items that required further treatment, were flagged up in an Excel document.

Geared up for another rehousing spree, I then moved onto to the most recent accession in the collection, the Acceptance in Lieu material, consisting of 18 boxes. The strategy this time was to start at the end of this series, giving back a bit more time and care to this series of records.

Loose-leaf material, now held in an acid-free paper fold

Being given the opportunity to support access and research into the Lyell Collection through conservation work has been a real privilege. As an aspiring paper conservator, it has been great to add a few more paper treatment strings to my bow, and to apply my skills to a collection this significant. By working closely with the Lyell Collection, I have also learnt a lot about him and the way in which he planned, researched and worked. I’ll leave all of you lovely Lyell fans with what is possibly my favourite thing that I have learnt whilst focusing on Lyell and his correspondence… apparently Charles Darwin enjoyed a good moan to his pals now and then like the rest of us!

A big thank you to all the conservation people who have contributed their time and skills, and to our funders for ensuring Lyell’s records are in the best condition they can be. There is always more work to be done – but for now, we can look to start the work to make these records available to people.