Home University of Edinburgh Library Essentials

December 15, 2025

New Data Curation Profiles: Edinburgh College of Art

Jane Furness, Academic Support Librarian, Edinburgh College of Art, has contributed two new data curation profiles to the DIY RDM Training Kit for Librarians on the MANTRA website. One data curation profile for Dr Angela McClanahan, and another data curation profile for Ed Hollis. Jane was one of eight librarians at the University of Edinburgh to take part in local data management training.

Jane has profiled data-related work by Dr Angela McClanahan, Lecturer in Visual Culture at the School of Art, Edinburgh College of Art. In the interview Angela discusses the importance of research data management, anonymisation and sharing, long term access to data, and the need to reconsider the term ‘data’ in an arts research context.

Jane has profiled data-related work by Ed Hollis, Deputy Director of Research, Edinburgh College of Art. In the interview Ed discusses the different data owners, rights and formats involved in researching and publishing a book, copyright issues of sharing data and the issue of referring to research materials as ‘data’ in the arts research context.

‘The old conditions cannot continue, and some new form of political and economic existence must be found’

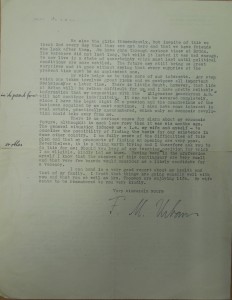

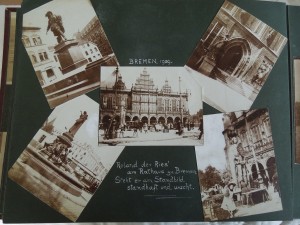

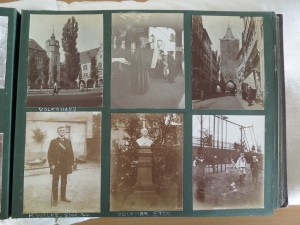

All of history seems to be contained in the letters of ordinary people living in extraordinary times. We may know what backdrop will emerge, but there are seldom enough traces to discover the fate of the individual. The following letter, sent by a Dr Friedrich M Urban of Brünn a short while after the Nuremberg rally of 1938 to Professor Godfrey Thomson, is a fascinating example:

It is not clear from Thomson’s papers how he knew Urban – quite possibly he had met him while studying in Strasburg, during which time he undertook a tour of Europe.

Urban’s letter shows a great deal of affection for Thomson and his wife, referring to the kindness of the Thomsons to their girls. Speaking to Thomson as an old friend, Urban thanks him for the suggestion of medicinal honey to help with his gallbladder, and reports on the method’s success! But the mood in the letter quickly turns:

Much has happened since we met and took those pleasant walks in the parc [sic] of the Spielberg. Our country was involved in a catastrophe which is bound to have the most serious consequences for its citizens. The old conditions cannot continue and some new form of political and economic existence must be found.

The first consequence was that we had to separate from our children. When we listened to Hitler’s speech at Nurenberg [sic] – for who did not? – we understood that he contemplated violent measures against our country. We wished to have the girls out of the way and asked Mr and Mrs Sanderson and Dr Fernberger for hospitality for our children. We got positive answers at once and managed to get the girls across the German frontiers. It was in the nick of time, for three weeks later the frontiers were closed.

There is much about the letter that is perplexing – initially, I thought Urban might have been writing from Brunn in Austria, but for the addition of the umlaut (both Germany and Austria have regions called Spielberg to confuse matters further). He could also have been writing from Brno in the Czech Republic, which does not seem an unlikely option considering Brno is home to Spielberg castle and was captured by Germany in 1939. However, it does seem rather unlikely that Urban would use the German spelling of his town in that instance.

If we are to assume that Urban is writing from Germany, his phrase ‘our country was involved in a catastrophe’ is an interesting one. The ‘catastrophe’ he refers to is likely the annexation of Austria by Germany, which took place earlier in the year. It was a catastrophe caused by Germany’s actions rather than their involvement, but he makes a clear distinction between the activities of the Nazis in this instance and ‘our’ country, his country, refusing to identify one with the other.

Urban tells how the girls stayed in London with the Sandersons for a few weeks, before sailing to New York where they remained in the custody of the Fernbergers in Philadelphia. He mentions how they are waiting for a letter describing the girls’ travels, but can’t hide quite how much they are missed:

We miss the girls tremendously, but inspite [sic] of this we thank God every day that they are not here and that we have friends who look after them.

He talks about how life at Brunn will likely become ‘rather difficult’, and asks for Thomson’s help in finding teaching work in Britain. While he accepts that this may be impossible, and admits his chances of securing work in Britain are ‘very small’, Urban remains optimistic nonetheless – thankful even – that his daughters are safe, and his health good. I can find no trace of Urban – whether he and his wife were ever reunited with their daughters remains a mystery. For me, this serves to make the letter, which describes the plight of millions throughout Europe from the perspective of one individual to another, all the more touching.

If you have any information regarding Dr Urban, do please comment.

New journal publishes using library service: Journal of Lithic Studies

The Library is pleased to announce the launch of the Journal of Lithic Studies. The Journal of Lithic Studies is published online by the School of History, Classics and Archaeology and is hosted by the University of Edinburgh Journal Hosting Service. All articles in JLS are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 UK: Scotland License.

JLS is a peer-reviewed, open access journal that focuses on archaeological research into the manufacture and use of stone tools, as well as the origin and properties of the raw materials used in their production. Coverage will include all geographic regions and time periods. Issues will be published twice a year in March and September, starting with March of this year.

JLS will publish research articles, short reports, and methodology demonstrations, as well as editorials, summary or synthesis articles, interviews, and reviews of books and events. As an electronic publication, authors can take advantage of the wide variety of media available in this format in addition to those available in the traditional paper format. At the moment, the journal is published in English but we are open to publishing issues in other languages in the future.

To receive future updates from JLS, please register on the journal’s website at http://journals.ed.ac.uk/lithicstudies/ .

For more information about the Journal Hosting Service, please email: onlinejournals@mlist.is.ed.ac.uk

University of Edinburgh Open Access update: Feb 2014

As of 27th Jan there are approximately 75,700 records in our Current Research Information System (PURE), of which 15,486 have open access documents available to the general public (20% open access). In addition there are 71 records with documents waiting for validation.

Looking specifically at just journal articles and conference proceedings:

| All time OA docs | Open access % | 2008 onwards OA docs | Open access % | |

| Medicine & Veterinary Medicine | 6450 | 26 | 4537 | 32 |

| Humanities & Social Science | 2667 | 19 | 2239 | 32 |

| Science & Engineering | 5514 | 22 | 3688 | 30 |

Monthly application figures to the Gold Open Access funds:

| Month | Applications to RCUK | Applications to Wellcome |

| October 2013 | 23 | – |

| November 2013 | 27 | 20 |

| December 2013 | 19 | 9 |

| January 2014 | 32 | 13 |

| February 2014 | 24 | 13 |

Status of the RCUK fund – currently there is £327,222 left in the fund, with an additional £65,011 committed on articles submitted for publication. Altogether the fund has 39% left in the account.

Status of the Wellcome fund – since the start of the new reporting period (November 2013) the cumulative open access spend has been £108,372

Volunteer of the Month – February 2014

Claire Rochet, Musical Instrument Museum Edinburgh Volunteer

I have been working with the Musical Instrument Collection since October and I had the chance as a volunteer to explore different areas of their two museums, St Cecilia’s Hall and the Reid Concert Hall. During the first 3 months, I was a guide at St Cecilia’s Hall, which was great as it permitted me to familiarise myself with the collection. During my Bachelor’s Degree and first Master’s Degree, I specialised in museology but never came across musicology which means that I was a complete beginner when I first started. Needless to say that I learnt a lot!

Since last month, I have been working in collaboration with Colette Bush, the Museums Galleries Scotland Intern based with the CRC and Museums, at the Reid Concert Hall, where we are in charge of reviewing the display of the collection. I am very excited about this project, even more so when I learnt that the Reid is actually the first purpose built establishment as an instrument museum in the world.

This project is connected to the redevelopment plan at St Cecilia’s Hall which will lead to its temporary closure next September for about a year or two. Until now, the musical instrument collection was equally spread out between both museums. During St Cecilia’s Hall’s closure, the collection will be only visible at the Reid which means the museum will become the collection’s main venue. One other aim of this project is to expand the museum’s engagement with the general public by making the content more accessible. In order to do that, we are planning a display based on thematics but we also intend to make the content of the cases more comprehensible by putting more explanatory labels and less instruments on display. Even if the Reid itself is quite small, the collection on display is actually quite extensive which can be quite disconcerting for the visitor (around 1000 items are on display!).

Although, the collection being first of all a teaching collection, it should still be complete enough so the music school can use the collection as a point of reference for their classes, which is a big challenge as we need to find the right balance between accessibility and educational purposes.

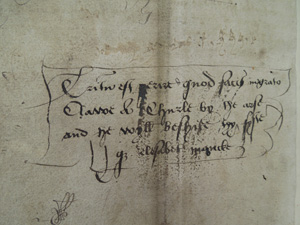

Medieval manuscripts behaving badly

This 15th century manuscript of the Chronicle of England ends with some rather surprising remarks on the flyleaf:

This 15th century manuscript of the Chronicle of England ends with some rather surprising remarks on the flyleaf:

Tritu est perire quod facis ingrato [what you do is lost by thankless wear and tear]

Clawe a Churle by the arse and he wyll beshite thy fyste quod elisabet moncke

It sounds as though the 16th-century Elizabeth Monk was having a particularly bad day. Thanks to Meg Laing from Linguistics and English Language for spotting this note, which is not recorded in the catalogue.

Europeana Cloud- Images Available

The Background (Norman Rodger, January 2014)

The University of Edinburgh, represented by Library and University Collections, is one of 35 partners in the Europeana Cloud Project, which is coordinated by The European Library. The project, which has a total budget of around 4.75 million euros, has just entered its second year and will run until January 2016.

Europeana Cloud will provide new content, new metadata, a new linked storage system, new tools and services for researchers and a new platform – Europeana Research. The project came about in recognition of the fact that content providers and aggregators across the European information landscape need a cheaper, more sustainable infrastructure that is capable of storing both metadata and content. Similarly, researchers require a digital space where they can undertake innovative exploration and analysis of Europe’s digitised content. Europeana Cloud aims meets these needs.

Our role in the project is principally to deliver digital content and we have already well exceeded our original target figure of 7,500, by submitting over 12,000 images. These will soon be available online through the Europeana website.

In addition we have hosted two workshops on the Legal and Economic aspects of the project and participated in two Expert Forums looking at how researchers could use Europeana to aid their work.

The Delivery (Scott Renton, February 2014)

The Digital Development and Projects and Innovation teams are pleased to announce that our main commitment to the Europeana Cloud project has now been fulfilled, and we have 12,431 CRC images across 16 datasets available in the Europeana repository. They’ve been harvested from the LUNA image service using OAI-PMH (harvesting), and the process has been, honestly, quite painless! There has been some development work to make the right information appear, but it’s always easier to let people get your stuff than to build something to send it to them. Crucially, the images on Europeana link back to LUNA, which will hopefully improve traffic to our collections.

The full set of images can be accessed here: When you get in, individual datasets can be accessed with the following (user-friendly!) search terms… don’t enter the bit in brackets!

- europeana_collectionName:9200259* (Architectural Drawings)

- europeana_collectionName:9200260* (Hill and Adamson Calotypes)

- europeana_collectionName:9200261* (Incunabula)

- europeana_collectionName:9200262* (David Laing Archive)

- europeana_collectionName:9200263* (New College)

- europeana_collectionName:9200264* (Oriental Manuscripts)

- europeana_collectionName:9200265* (Salvesen Whaling Expeditions)

- europeana_collectionName:9200266* (School of Scottish Studies Photographic Archive)

- europeana_collectionName:9200267* (Walter Scott Collection)

- europeana_collectionName:9200268* (Western Mediaeval Manuscripts)

- europeana_collectionName:9200269* (Shakespeare)

- europeana_collectionName:9200270* (Thomson-Walker Portraits of Medical Men)

- europeana_collectionName:9200271* (CRC Gallimaufry (Miscellaneous Images))

- europeana_collectionName:9200272* (Roslin Glass Slides)

- europeana_collectionName:9200273* (University of Edinburgh- People, Places and Events)

- europeana_collectionName:9200274* (Object Lessons Exhibition)

Also on Europeana are our Musical Instruments from the MIMEd, which were harvested for the MIMO project in 2011. You can see those here.

Thanks as ever to Norman Rodger and Stuart Lewis for steering the project from our perspective! There will be a chance for the insitutions that have submitted to Europeana Cloud to meet up and share their experiences at the AGM in Athens next month.

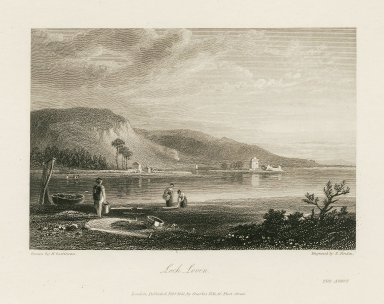

A Europeana Cloud image: Walter Scott’s The Abbot (Steel engraving by E.F. Finden from a drawing by H. Gastineau depicting a scene of Loch Leven).

This can be found at http://images.is.ed.ac.uk/luna/servlet/s/8vr814

and http://www.europeana.eu/portal/record/9200267/BibliographicResource_3000059119960_source.html?start=1&query=gastineau+leven&startPage=1&rows=12

Innovative Learning Week at University of Edinburgh

The Digital Imaging Unit filmed various Pecha Kucha as part of Innovative Learning Week February 2014. A few of the talks are available on the CRC Facebook page at : https://www.facebook.com/media/set/?set=vb.162317950517200&type=2

Malcolm Brown

Access To Research – A Public Library Initiative

Introduction

In January 2014 the Access to Research initiative was launched. This initiative was sparked by and is a response to a key recommendation in the Finch Report – “Accessibility, sustainability, excellence: how to expand access to research publications” (Page 7; recommendation v). The two year pilot co-ordinated by the Publishers Licensing Society aims to give free at the point of use, walk-in access to academic literature in public libraries across the UK. The launch quickly generated a fair amount of publicity, albeit with equal measures of scorn poured upon it.

This blog post is not going to spend a long time explaining what the initiative is and how it works – others do it better here – but rather I’d like to talk about some of the good points and some of the not so obvious bad points so you can make up your own mind on the matter.

Before we start, it should be pointed out that, despite arising from the Finch report which has rather a lot to say about open access, this initiative actually has nothing to do with open access as most people understand the term, and should not be confused with developments in this area.

Lets begin by looking at some of the good stuff that the initiative promises:

1. Costs

Firstly, the cost to participating libraries and the general public is zero. The initiative is intended to be free at point of use for the user, and free for libraries to sign up to participate with all the costs being borne by the publishers. While we are not aware of the actual costs they are presumably not trivial. Hazarding an educated guess I doubt you’ll see much change from £100k if you wanted to set up a two year pilot preceded by a 3 month technical trial.

2. Content

The 17 publishers that are included at the start of the pilot have contributed between 1.25 to 1.5 million articles from a portfolio of approximately 8000 journals. The figures remain a bit hazy as David Willetts in his launch presentation mentions one figure and the promotional text states another. However, knowing how these kind of statistics are pulled together I can appreciate the vagueness. At a first glance this is a sizable corpus of material to access for free, although I will return to this point to put the figure in more context later on.

3. Building bridges

One of the less tangible benefits of this initiative is that it could help to break down barriers between research and the wider community. The portrayal of science in the popular media is personal bug bear of mine. For many people the only exposure they have to current research topics is when they are covered in the newspapers and television news. Unfortunately lazy journalism seems to propagate an ‘us v them’ mentality – one of the most commonly heard phrases in the news must be “Scientists state that X causes cancer*” which is rarely productive for all involved. If journalists or the public can engage better with the primary literature (i.e. find more interesting news articles to broadcast/ carry out follow up reading) then this can only help with perceptions and engagement with research. Even proponents of the Access to Research initiative admit that a key challenge is how to digest information obtained from scholarly journals. At least making the literature available for citizens to begin to make informed decisions is a good start.

*where X is an activity/thing regularly done/consumed by the public

4. Footfall

At a time when public libraries are struggling in the face of cuts to maintain services and prove their relevance librarians will seize upon any opportunity to offer more services for no initial outlay (other than staff training). Already there is anecdotal evidence* that offering new services such as Access to Research will entice new users who wouldn’t normally think of visiting. Although most people would agree that providing information online is much more desirable, an increased footfall at public libraries is a good thing.

* Sarah Faulder at 7min20 mentions “ ….a glowing testimonial”

5. Usability

Although I’ve not yet actually used the pilot Access to Research service, from all accounts the search delivery service – Summon from ProQuest – is extremely easy to use and doesn’t require specialised training to use. Furthermore, it doesn’t require tricky authentication to access on site which is a major failing whenever I’ve tried to use some online electronic public library services in the past.

6. Leadership

Another less tangible benefit mentioned by David Willetts is ‘thought leadership’ and UK PLC to be seen to be doing the right thing.

Now lets move on to some of the criticisms raised against the initiative:

1. Terms & Conditions

Perhaps some of the most serious criticisms are the limitations imposed on accessing the content. It always pays to read the small print which reveals serious restrictions on use – here are some of the worst:

- I will only use the publications accessed through this search for my own personal, e.g. non-commercial research and private study

- I will not download onto disc, CD or USB memory sticks or other portable devices or otherwise save, any publications accessed through this search;

- I will not allow the making of any derivative works from any of the publications accessed through this search;

- I will not copy otherwise retain, store or divert any of the publications accessed through this search onto my own personal systems;

Some of these points are extremely patronising – the derivative works one for example. We have all heard the famous quote that science is based upon standing on the shoulders of giants. To not be able to make derivative works goes against one of the underlying principles of scholarship. What this point makes clear is that users are meant to be consumers not creators of knowledge.

Other more knowledgeable folk like Cameron Neylon make a more eloquent assessment of the problems these terms and conditions create. All I want to add to this discussion is that in this day and age there is no reason to force users to adopt restrictions on use that are only appropriate for print media, unless you wish to severely handicap the usefulness and therefore the uptake of the service.

2. Postcode lottery

Closely related to the point above, but sufficiently serious to warrant its own point is the postcode lottery of whether you can actually use the walk in service. With 10 local authorities participating in the technical pilot and 11 new authorities joining, that means there are 400 libraries at the start of the initiative. There are around 4,265 public libraries which means the coverage is less than 10%. You could say that some access to public is better than no access at all, however the fact remains that currently the majority of UK citizens are excluded from the service. In mitigation, this is the start of a 2 year pilot and the initiative hopes to sign up a lot more local authorities as the pilot progresses. I would fully expect coverage to increase over time as more libraries opt in – although it’s hard to estimate quite what the final coverage will be.

3. Content put in context

1.25 – 1.5 million articles sound like a lot of content to read. However, if you consider that there are around 46.1 million records in Web of Science; and it is estimated that in 2006 the total number of articles published was approximately 1.35 million, the range of articles you can access through the initiative is a drop in the ocean. So if you are lucky to live close to enough to walk in to a participating library you can only access the equivalent of the research that was produced last year. As far as I know the selection process to be included in Access to Research is opaque – what papers are chosen and who decides?

4. Preserving the status quo

Perhaps one the most disappointing points for me is that this initiative is trying to preserve the status quo of academic publishing. It’s firmly rooted in the print distribution model and has built in sufficient obstacles for users to overcome that it is setting itself up for failure. The initiative goes against nearly all of Ranganathan’s five laws of library science:

i. Books are for use

…but the articles are digitally chained to prevent their removal.

ii. Every reader his [or her] book

…but the majority of readers can’t visit a participating library

iii. Every book its reader

…but the portfolio of journals is not comprehensive.

iv. Save the time of the reader

….restrictive terms and conditions prevent this.

v. The library is a growing organism.

….perhaps this is the saving grace as there is room for improvement.

5. Motivations

I’d like to take time to consider the motivations behind the initiative. Commercial organisations do not do anything for free unless there is a benefit somewhere further along the line. To put it in the crudest possible terms the benefits are the holy trinity ofcash, turf or fame. The Access to Research initiative certainly ticks all three of these boxes.

The Publishers Licensing Society who have co-ordinated the Access to Research initiative, and Nature Publishing Group have been very forthright in admitting that the scheme is about ‘creating a new audience for information’ and opening ‘another channel to the market’ for their content. I can’t comment on how publishers actually intend to monetise the situation, but the standard Modus operandi is to develop a market then sell products directly to it.

It has been widely commented that there has been a great deal of hard lobbying by publishers to position paid-for Gold Open Access services as the main method of delivery of open access in the Finch Report. The focus on Gold OA has been widely criticised by a broad spectrum of the academic community and has resulted in a partial backtrack. In the face of renewed criticism academic publishers will be keen to please to government and show everyone they are the good guys:

“Government has been extremely pleased to see how publishers have tenaciously pursued their welcome proposal for a Public Library Initiative (PLI) in the national and public interest.”

Certainly the response (above) from the Rt Hon David Willetts to Prof Dame Janet Finch indicates they are heading along the right lines.

6. Access to public funded research

In the last few years there has been legislative movement in the States pushing towards taxpayer access to publicly funded research, and this viewpoint is gaining momentum in the UK. One of the main criticisms levelled at the current subscription model is that public funded money is being used to produce the research, but the fruits of the labour are not available to the people who funded it. One way to stop dead this argument is to say the public has access to all the research they need through an initiative like Access to Research.

Personally I would rather not rely on the generosity of third parties to deliver a sub-set of content (from an opaque selection of materials), that can have access removed at any time (2 year pilot), and is made difficult to access (via restrictive terms and conditions of use). I would rather see all content funded by taxpayers (either directly via research councils, or indirectly via universities or other sources) to be available freely via the internet (either in a repository or via an open access publisher), preferably with generous reuse rights granted up front.

The Too Long; Didn’t Read (tl;dr) summary

My own personal take on all of this is that the ‘Access to Research’ is a step in the right direction, but falls short in the implementation, and is driven by motivations that are not so altruistic as you might first think.

Volunteering in the DIU

I have been volunteering with the Digital Imaging Unit for about a year, during which time I have been researching and adding metadata to their digital collection, as well as selecting images for a recent postcard project. It has been a wonderful opportunity to get to know the breadth of the University’s Collections and contribute to its online visibility.

As a student of the (MA) Fine Art degree looking to start a career in the archive and museum sector, volunteering with the DIU has not only provided me with relevant work experience, but also enriched my visual and art historical knowledge by exposing me to an incredible variety of pictorial material.

The collection has a number of beautiful images of old Edinburgh and it is remarkable to see how, in some ways, so little has changed in the city landscape.

Glass-plate slides are such wonderful objects and these have incredibly vibrant colours. This particular image seems to be a photograph of the Bois de Boulogne, a park close to where my grandmother lived in Paris.

The Capybaras, or Capivaras, are a type of giant rodents indigenous to the region I grew up in Brazil. It was a lovely surprise to discover this image in the University’s collection of Zoological Illustrations.

One of the many fascinating items I’ve had the pleasure to research for the DIU, a 17th century book detailing comet sightings throughout history, accompanied by intricate illustrations.

Pigs, pumpkins and ostriches… what more could you want?

Alice Tod

Collections

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Projects

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....